Guy’s Doll—Sheila Connolly & Guy Madison

Sheila Madison can best be described by the lyrics of a recent song: “A doll I can carry the girl that I marry must be.” The girl that Guy married is a doll, for sure. Add to that the following: lively as a cricket, piquant of expression, droll of wit, feminine without any compulsion to rub the noses of nearby males in an awareness of same and completely at home in the world.

Sheila is most frequently compared to Elizabeth Taylor, probably because they’re both girls and in Hollywood you’ve got to look like some star unless you have two heads, and Sheila is small and brunette.

A surprising type to attract Guy Madison? No, the right type exactly, according to his friends. “Sheila’s very good for Guy,” commented Rory Calhoun’s wife Lita. “He’s getting from her what he never got from anyone before. She shows him the way because she’s so outgoing with people and they respond to her warmth. He’s learning to relax more with them.

“There was a time, before they met, when Guy had dinner with us almost every night. When Billy Daniel and I were at the Mocambo, Guy even came there with Rory—and neither of them is the night-club type. Guy was terribly gay then, he seemed happy living it up, but I know that it isn’t his nature. With Sheila he can be himself. You know, quiet-like.”

Probably one of the first qualities that attracted Guy to his bride, aside from the fact that he had all of his hormones, was her self-sufficiency and an honesty that insists on the truth, just the plain truth. If Sheila were Hollywood-struck, she might say of her father, “He owned the biggest racing stable in all of Ireland.” Instead of which she states with complete aplomb, “He was a jockey.”

Similarly, though any good press agent would tell her not to discuss a conflict in religions, she does, because it explains how she came to be born in America. “When my mother and father fell in love, her parents nearly had a fit, they being Protestant and he a Catholic. They came up with a great idea: separate the two, send her to New York to visit relatives. They didn’t know my Pop. All he did was to follow her to New York, where it was much easier to talk her into marriage. It’s funny. My mother was a convert and she became the best Catholic of us all.”

A romance could, perhaps, be broken up, but an established family could hardly be made to disappear into thin air, so after Sheila was born her father felt safe in returning to the Ould Sod, where his name was already well known in the racing world. And there Sheila grew up knowing the costumes, the customs and the ways of a little Irish girl. She was not to see the land of her birth again until she was fifteen. Her first impression? “That school here was so hard. I thought I should never catch up.”

Sheila’s interest in acting was awakened in a curious, somewhat comic way. The first job she ever applied for was that of an unglamorous, ordinary telephone operator. She learned the mechanics of a switchboard easily enough; but perplexed customers of the telephone company were unable to translate her impenetrable Irish brogue. So Sheila learned to speak English. Dramatics was also taught at the school where she studied elocution and so she only had to take a single step in the direction pointed out by fate.

Before long her heart was set on Hollywood. Sheila worked regular shifts as a long-distance operator and picked up extra money as a beautiful model. “It didn’t take long to save enough,” she points out, “because I didn’t need so very much. Friends had already invited me out to pay them a long visit.”

Sheila got a screen test at Paramount by the simple device of walking in and asking for one. The clouds were her stamping ground—but only for the sweetest, briefest moment. Nothing came of the test, nothing came of anything. A few minor TV bits, but scarcely enough to keep beans in the dinner pot. When her resources were reduced to the price of a ticket home, she bought one.

Guy Madison didn’t meet Sheila on her first trip west. He was busy surviving a pretty rocky time himself. Back in 1946, when he made Cinderella look like a piker by the magnitude of his overnight success, Guy told a reporter, “I felt a tap on the shoulder and I was in. I’m not expecting any joyride and I intend to work hard. Because all I need is another tap to be out again.”

The trouble was, he hadn’t: time for all the hard work he planned before the second imperceptible tap came. With the total experience of about seven minutes on film in Since You Went Away, Guy was immediately cast in big-budget pictures which demanded far more of him than his limited knowledge of acting could produce, and he fell on his face with a thud heard around the world. Guy suffered. His audiences suffered. His boss David O. Selznick did not. While Guy was distinguishing himself by spectacularly wooden, self-conscious performances, he was on loan-out to other studios and incidentally earning Mr. Selznick some $150,000. By comparison, his own top salary at the time was $600 a week.

After three or four pictures that had best be forgotten, Guy Madison was washed up.

The incredible masculine beauty remained, the animal grace remained, but how did you sell them to an industry convinced that their-possessor was the world’s worst actor? Two people were not convinced: a very stubborn young man named Guy Madison, and Helen Ainsworth, the agent whose persistence had brought him to Hollywood in the first place. There was a difference, they believed, between a lousy actor and an inexperienced one, so the kid from Pumpkin Center, California, hit the road to learn the rudiments of his craft.

For eight months Guy played summer stock, tackled any form of theatre that came to hand. Stubbornly, he held on until TV gave him the break that put him back in business. (TV and Sheila, too.)

With his comeback assured by the phenomenal success of Wild Bill Hickok, and picture studios making their usual preposterous efforts to outbid each other for his services, Guy’s personal life became a trial by ordeal. His deeply-felt marriage to Gail Russell was admitted to be a failure. This is the time friends remember Guy’s being feverishly gay. He had won one tremendous battle against all odds, only to find that he had lost another.

The stage was set for love when the lovely little Irish girl came riding back to Hollywood on a new and reinforced bankroll. Sheila and Guy met on April 15, 1954, when the annual Sportsman’s Show was held at the Pan Pacific Auditorium. It figured that Guy Madison would be at any sports show anywhere, but Sheila Connolly was there only by chance. A friend of hers worked for the show’s publicity director and got her in for free; otherwise she might have been ten other places that night.

They were strolling around from one exhibit to another when Barbara nudged her. “Look! There’s Guy Madison!”

Sheila looked. She recalls thinking that he was extraordinarily handsome, even for an actor. They were introduced, inspected each other briefly and went their separate ways. “Ah, but then,” as Sheila tells it, “we were invited to a little cocktail party upstairs, which was Guy’s doing. He wanted-us there. As soon as we came in, he came over and started talking. I never remembered to ask what happened to my friends that night. It was Guy who took me home.”

To hear Sheila tell it he was a regular little old chatterbox on the drive to her apartment, musing over the sound of Ireland in her name, teasing her about the probably low flash point of her temper, talking about his own family, enthusing about hunting, fishing, Andy Devine and sundry other subjects. “He talked so much that I was surprised to learn that he had a reputation as the strong, silent type!”

One of the things they talked about was her phone number. Guy found a piece of paper, then slapped his pockets in disgust. “No pencil.”

“Oh,” Sheila’s hand went to her purse, “I always carry one.” Except this time.

“Okay, I’ll remember it, anyhow.”

Sure you will, Sheila thought to herself as they said good night. An hour later the phone at her bedside rang, and she murmured a drowsy, “Lo?”

“You see?” said the triumphant voice of Guy. “I told you I’d remember!”

All of a sudden she was wide awake again. It was a distinctly pleasurable feeling, talking to him a little while longer, even if he said good night the second time with a vague, “I’ll call you.”

Better that she didn’t hold her breath until he did call. She read in the trade papers the next day that he was off on a hunting trip, she read about it when he got back to town. She thought it was nice of the columnists to report his activities, since she obviously wasn’t going to hear about them first hand. Guy maintained his silence for two months, until the interlocutory decree in his divorce case was handed down. Sheila can take comfort from the fact that she was the first girl he did call as soon as he was free. By the time they were ready to leave her apartment on their first date, he had already learned that she wasn’t much of a cook. At that point the telephone rang; it was Sheila’s father, calling from New York.

“I want to talk to him,” Guy said, and after identifying himself, announced to the astonished Hibernian across the country, “This is a pretty nice little girl you have here, sir, but she needs some training around the house, for sure.” Sheila doesn’t know what her father answered, only that their masculine agreement must have been instantaneous. Guy grinned hugely, and the last thing he said to his future father-in-law was, “Well, I think a couple of good beatings ought to do it.”

How long did he court her before they decided to marry? “About twenty-four hours,” Sheila will tell you, because she always teases a little first. “No, actually we went together for months. What I mean is that it couldhave happened in twenty-four hours. Have you ever met someone whom you felt you’d always known? That’s the way it was with us. When he told me something happened before I knew him, it was like having something I already knew confirmed. And I didn’t really have to tell him about my childhood in Ireland; he might just as well have grown up with me.”

Guy never actually proposed—“He sort of got around to it by degrees”—but it had been his decision to obtain that Mexican divorce so they might be married without further delay. When Hedda Hopper reminded him that Mexican marriages and divorces end up sometimes yea and sometimes nay, Guy answered, ‘Hedda, you’re talking to a marrying kind of man who is really in love. I’ve been alone too long.” And, having summed up his life in those few poignant words, Guy took his girl down to Juarez and got married.

Guy has changed since he first hit Hollywood. Many men fall apart under stress; Guy found unsuspected strength and maturity through pain, hardship and professional humiliation. He isn’t an impossibly beautiful, golden-haired boy anymore, but a dynamic man tested and found true. To his credit, bitterness is still a stranger to Guy. Recalling the stark years, he is apt to shrug and say, “Hollywood gave me the chance to make more money than I could any other way. I have reason to be grateful.”

Guy’s still taciturn, but there is the steel of self-assurance behind his wariness, the diffidence has developed naturally into reserve and the naiveté is long since gone. More recently departed but equally unlamented is the solemnity; the slow smile starts so often in Guy’s hazel eyes these days that his more intrepid friends presume to call him Laughing Boy.

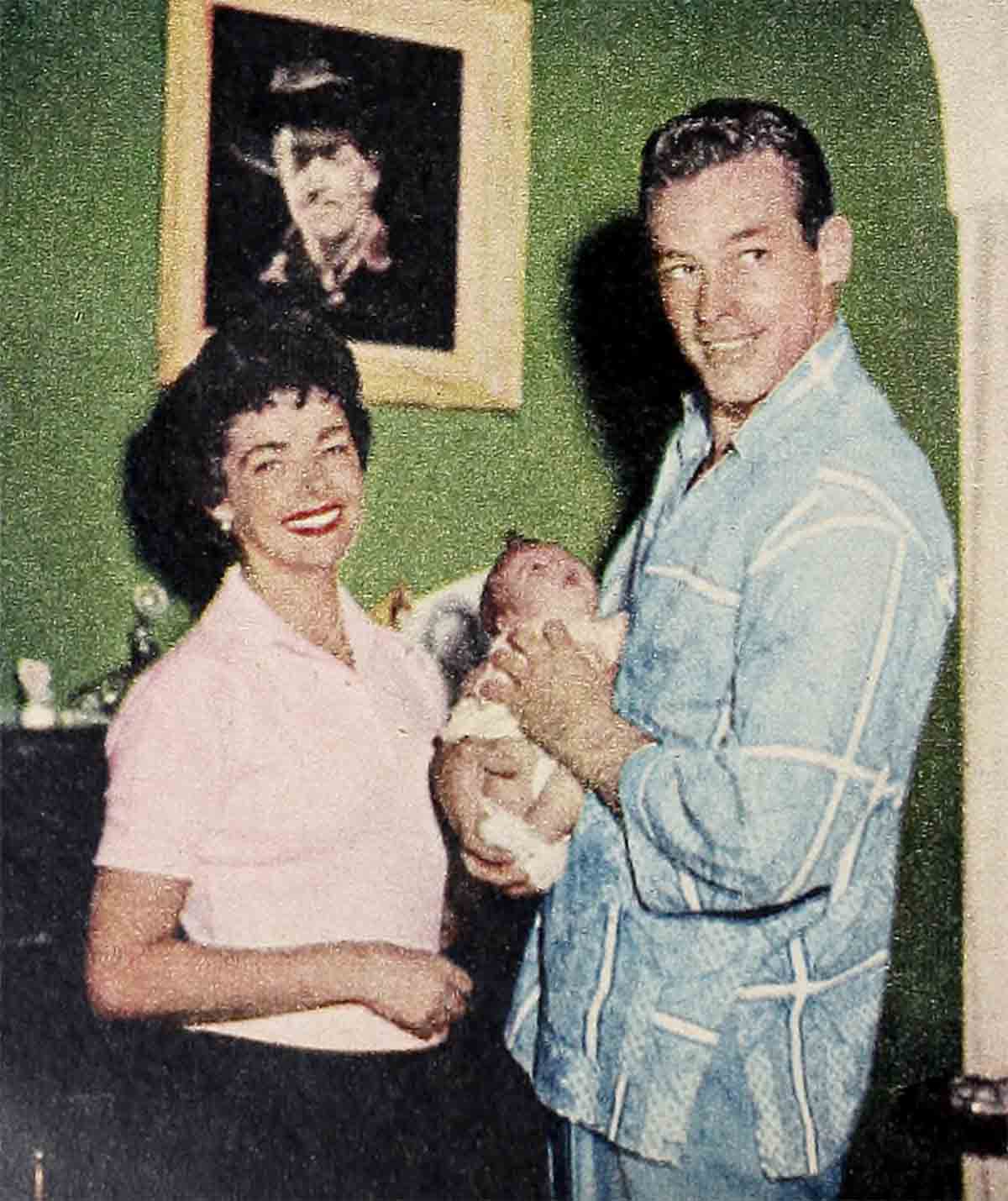

The change has come about partly because Guy feels his responsibility toward the enchanting girl he wooed and won. (From his attitude toward redhaired Bridget born to them this year you would think no man had ever been a father before.) Partly because he is a settled, domesticated, brand-new home owner. And partly because he learned his trade the really hard way—from the top down—and isn’t likely to make the same mistakes twice.

As for the girl that Guy married—she hasn’t tried to change him, being as how she fell in love with the man that he is. There is the possibility, though, that he might be influenced by what she gives him: the simple life he craves, a sense of emotional security, her own love of life and her priceless gift of laughter.

One friend described Sheila’s influence this way. “Guy is basically simple. He doesn’t feel like a movie star and he doesn’t like to live like one. Sheila’s good for him in that way, too. I believe he has bought her a little station wagon of her own now, but when they only had one car, she used to drive him to the studio like any other housewife driving her husband to his job. She looks after his clothes; when he comes home at night, she cooks for him. At the end of the day he’s as tired as any other working man and has the same reluctance to go out on the town, which Sheila understands. That way life makes sense. Maybe he earns his living in an unusual way, but the normalcy of their personal life keeps everything else in focus for Guy.”

Certainly not the least of Sheila’s gifts is the ability to make Guy feel that he is her lord and master. Take last week, for instance. Guy had been on location for a fortnight, putting another TV series on film, and Sheila hadn’t seen him for that long. She wore a properly doleful Irish face (just short of wurrah, wurrah) as she sighed and said, “He gets back tomorrow, but he’s leaving right away to go boar hunting. But I know he won’t let me go along; he thinks it’s too dangerous.”

Next day there was a brief item in one of the trade papers which said, “Sheila and Guy Madison are over on Catalina Island, hunting wild boars and things.” Of course Guy’s the boss. Everybody knows that.

THE END

—BY TONI NOEL

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1955