So, Sue Me!—Robert Mitchum

Any accident that’s on its way to happen just waits around for Robert Mitchum to stroll by. Then it happens to him. He is philosophical about it. He knows he must take the falls, but he doesn’t know why.

The trouble is that Mitchum thinks he’s just like other men. He isn’t. “Mitch is a classic in himself,” said an admiring Jane Russell, his longtime stablemate at RKO. “He can do anything—act, write, sing—just a little bit better than anyone else.”

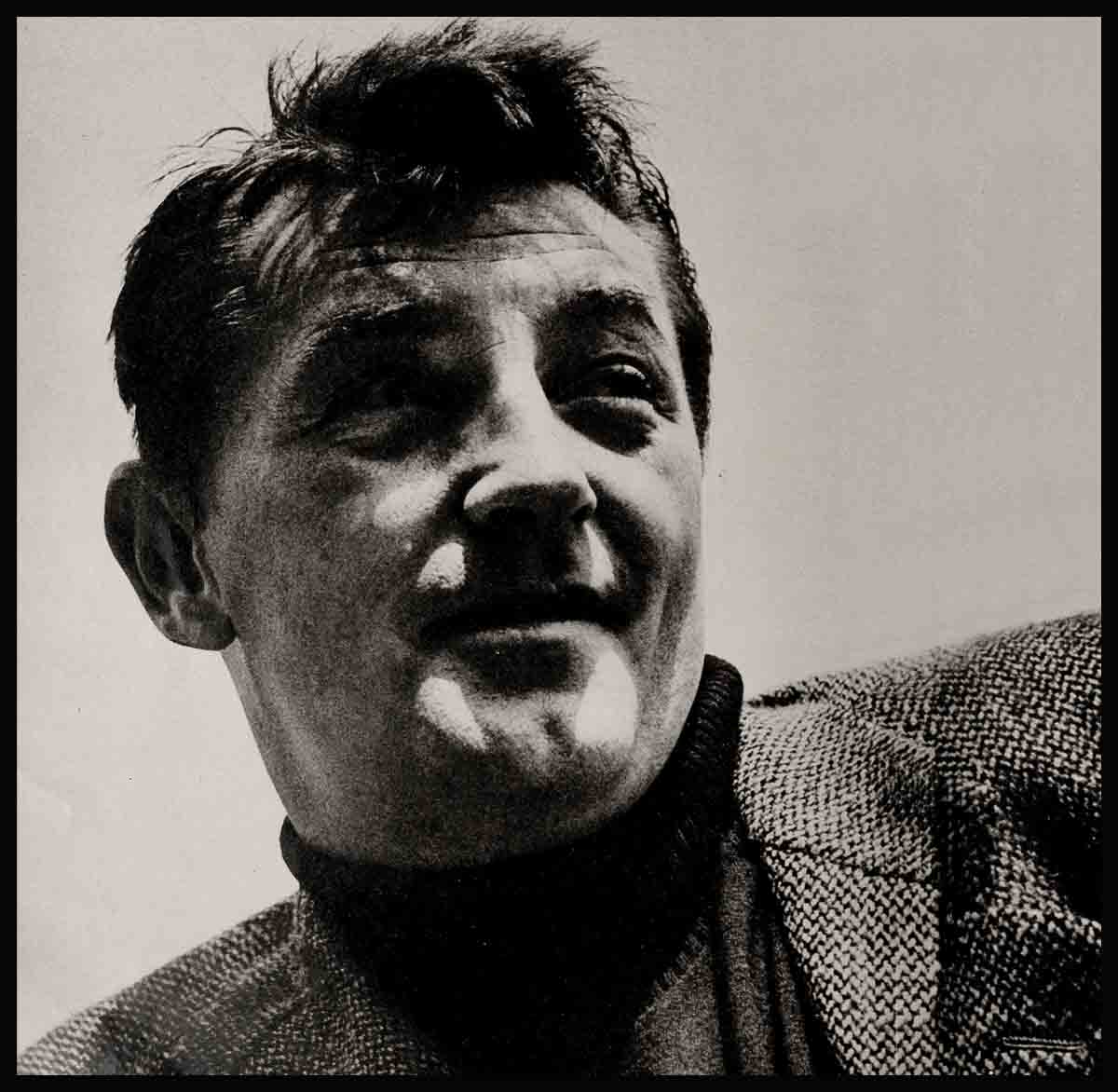

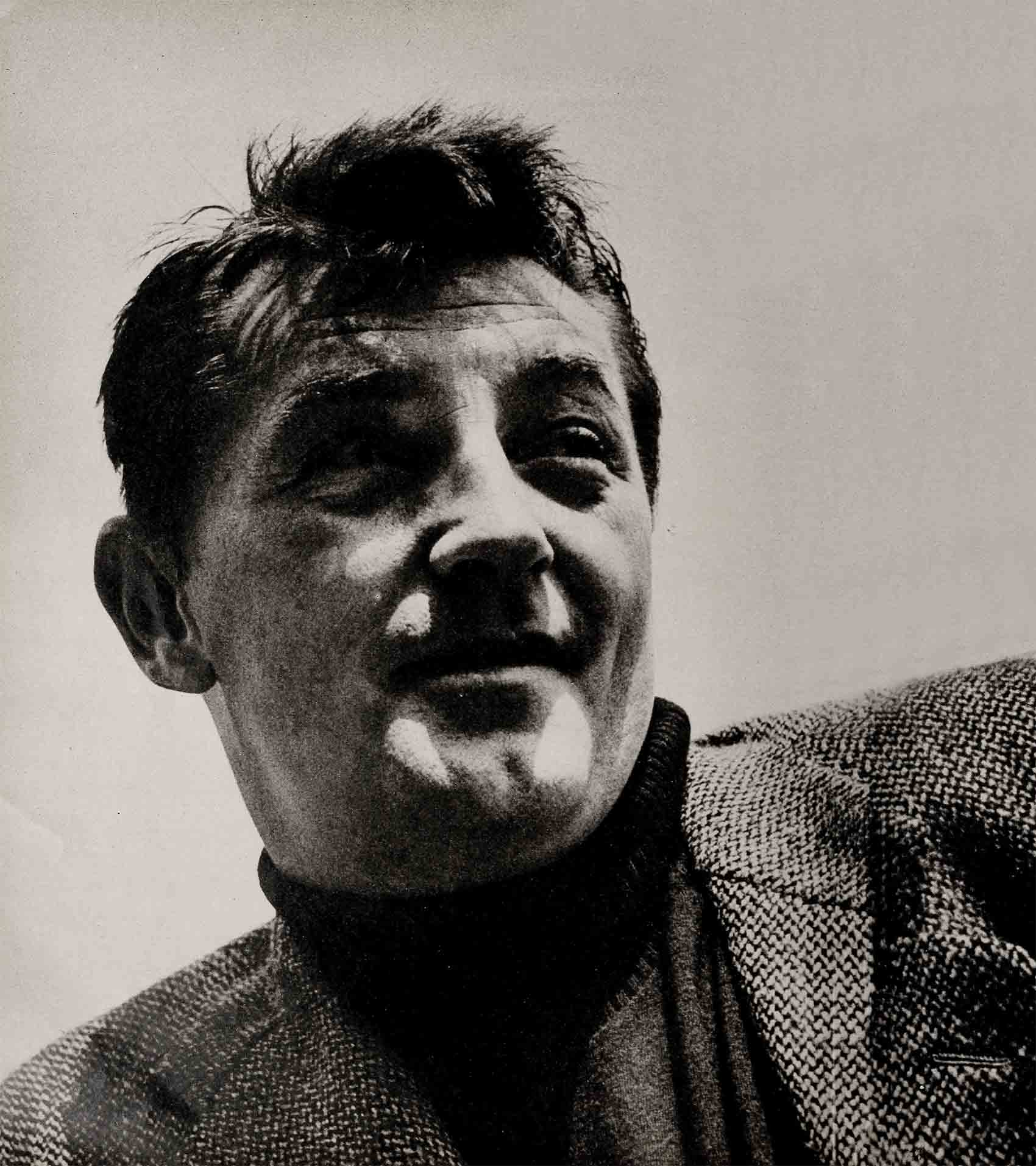

Mr. Mitchum is a mere six-foot, one-inch, hundred-and-eighty pounder, but he looks immense, possibly because of the tremendous breadth of his chest and shoulders. Physically, he’s a man women must look up to, which makes him different from the average run of Hollywood males. And there are other differences.

Male stars tend to fall into two camps as to hairstyle. The younger heroes like the swirl-about that results in careless curls; the aging idols prefer the crewcut as a means of maintaining the illusion of youth. Our Robert wears his light brown hair in a spiky, bristling in-between that goes nowhere. Ladies tenderly describe it as “stubborn.”

The Mitchum profile, altered if not improved by a broken nose, strikes them as exceedingly manly. If any other gentleman appraised them with sleepy-eyed boldness equal to that of his hazel eyes or with such a curling lip, they’d exclaim, “How dare you!” To Mitch they murmur, “Why don’t you?”

Other guys could walk on their hands without attracting the amount of feminine attention Mitchum achieves simply by putting one foot before the other in the prescribed manner; the delighted distaff reaction to his relaxed amble is that of hep cats to catnip.

Women he has never seen before in his life make outrageous requests ranging from “one kiss” to his autograph on their unmentionables. To comply would require an abundance of hormones unknown outside the realm of rabbits, which Bob Mitchum has never claimed. It is to his credit, however, that he doesn’t hold a low opinion of the feminine gender because of this tendency to melt into absurd puddles in his presence. He probably thinks it happens to all the boys.

Nor is his impact limited to those age groups which should still be receiving such emotional charges. At a recent dinner party an exquisite dowager of seventy years sought to question a screen writer closely about the Real Robert Mitchum. When the writer admitted that he hadn’t met Mitchum, he might just as well have gotten lost.

“Now, there,” she stated unequivocally, “is the only actor in pictures I’d walk across the street to see. And the only man in the world I’d still like to meet.”

The other guests were amused, since she was such an elegant little thing, and they began to tease her.

“Dulcie,’ said one, “I don’t think Mitchum is your sort, really. His choice of words is rather Edwardian, you know.”

She was unperturbed. “I never knew a real man who didn’t use strong language when it was provoked.”

“But Dulcie,” protested another, “he’s supposed to be a terrible roué! I’ve heard that his leading ladies fight over him.”

Dulcie smiled. “If it’s true, it certainly proves that he’s a man, doesn’t it?”

Dulcie’s husband thought that the conversation should have exhausted itself by now. “Dulcie,” he said irritably, “may I remind you that your charming Mr. Mitchum has been suspected of getting his kicks from something stronger than cornsilk?” It should have worked, but this was Mitchum they were discussing. In the loaded silence that followed, Dulcie leaned forward. “Tell me,” she asked sweetly of her husband, “is it fattening?”

The first picture of Robert Mitchum drawn by the pens of Hollywood writers was that of a crude, rough-and-tumble character possessed of nothing more than pure animal magnetism. Having been variously a longshoreman, a carny, a bouncer, a truck driver and a hobo, he was a tough guy and it showed; he appealed to a lady’s baser instincts. When that characterization palled, the present one was superimposed. Bob Mitchum isn’t a tough guy any more. Instead, he’s a brilliant, shy, sensitive introvert, hiding his feeling of personal inadequacy behind a facade of cynicism and blasphemy.

This is the stuff of which fables are made. Certainly Mitch is bright, talented and acutely sensitive to the vibrations of his fellow beings—but never be deluded into thinking he’s a shrinking violet whose virility is confined to his press clippings. When the men were separated from the boys, Mitch was there to be counted among the men. He can take care of himself, as he proved a few years back when he had a donnybrook with a large gentleman in Colorado. The gentleman was a professional fighter whose record indicated that he had knocked out nineteen of twenty-eight opponents in the ring. The record of Robert Mitchum wasn’t available. The cause of their altercation was never established, but when the dust settled there wasn’t a mark on Mitchum and his antagonist was resting as comfortably as could be expected in the local dispensary. Said an apologetic Mitch to the press, “All my fault,” which was certainly the truth; there was nothing to indicate that the pugilist had planned a rest cure at that particular time. Then Mitch added, “An actor is always a target for belligerent guys who think that they are tough and Hollywood he-men are softies. Sometimes you have to fight.”

Bob Mitchum believes he is a cynic about humanity. Once he said, “I’ve been places where men would kill you for the shoes on your feet. I don’t have to think twice about what they’d do to you here in Hollywood for a million bucks.” From what bitter experience he gained this profound knowledge he didn’t say, but it did absolutely nothing to prevent him from hiring a business manager who absconded with $83,000 of his money. It wiped out the Mitchums after five long years of working and saving.

Even now he is no less susceptible to the blandishments of people who entertain similar intentions. A case in point is his recent venture into the field of popular music. Though he’s no Cole Porter, Mitch has a good feeling for music, and when he can’t think of a song to fit his mood, he makes one up. Now and then they’re pretty good.

He showed one such improvisation to “a guy”—Mitch never identifies them beyond that—and after a little time the guy approached him enthusiastically. “I think I have a good chance of getting your song published. Will you sign this, so I can get a rating?”

Bob signed. A few months passed, and he heard his song played on a disc jockey’s program, just as you probably did. That was absolutely all he heard, however—his song being played—until an agent from the Bureau of Internal Revenue asked him for an accounting of his royalties!

“I just told him.the truth, that I hadn’t made a dime. I didn’t mind the guy making money off my song,” he said wryly, “but I thought the least he could do was pay the taxes on what he made.”

Cynic or no, Mitch is oddly philosophical about getting rooked. Maybe it’s easier to practice philosophy than to admit people aren’t always good. But according to him, it’s the breaks. The man who stole his $83,000 is in prison, and he doesn’t write songs to make money, anyhow. The big shoulders shrug in ageless acceptance. “You get a bad break, you just fight a little harder.”

It isn’t the way most men would think. Mitch doesn’t think like other people, and because he doesn’t, because he is literally a free soul, he is terribly vulnerable. He hasn’t done half the things with which he is identified—but he might if he felt like it. Therefore any story about him is credible. Accuse him of anything in the world, and at least a few of his best friends will believe it. Why not? It’s possible.

Mitch can’t shake the character traits that make him vulnerable, but he’s getting used to being a sitting duck on the pond. There was quite a newspaper spread last year about his being arrested for driving his Jaguar seventy miles an hour down Wilshire Boulevard. At the preliminary hearing Mitchum sat slouched down, talking to “a guy” who might have been a reporter, a lawyer or even a policeman. The guy said, “You’ll be cleared if you take it to court; you’re innocent on the evidence against you. Heavy as the traffic is on Wilshire at eight o’clock at night, you couldn’t go seventy unless you were in a helicopter.”

“So I take it to court and I’m cleared,” Mitchum said. “Then what happens?”

The guy was elaborately casual. “Oh, the officer who made the mistake will get suspended or dropped from the force. He probably has a family, and the rest of the men on the traffic detail aren’t going to forget that you cost him his job. Natural enough, isn’t it? You can afford a traffic citation a lot easier than he can afford to admit a mistake that may cost him his job.”

Mitch pondered. “So?”

“So, if you’re smart, you plead guilty to speeding, reckless driving, resisting arrest, or whatever you’re charged with. Pay your fine and forget about it. Otherwise, you get a lot of unpleasant publicity and the assurance that every time you run an amber light from now on, you’ll get another ticket. Cops aren’t mean, but they’re human.”

Bob Mitchum, boy cynic, shook his head. “Took, I just don’t get it. This other actor, the one they caught last week—he was doing ninety. The only way they stopped him was to pump five bullets into his car, and when they opened the door he was so drunk he fell out on his face. How come he gets off with a fine for drunk driving and three lines in the newspaper, and I get the book?”

“Ah,” answered his adviser, pointing the finger of sardonic truth. “They don’t want to read about him. They want to read about you.”

Mitchum meekly pleaded guilty and paid. He’s getting used to it.

Not unexpectedly, publicity-seekers take wide advantage of the fact that people want to read about Robert Mitchum. It was this and nothing more that precipitated the now-notorious breast-baring incident when Bob and his wife attended the Cannes Film Festival. Summing it up, a hitherto un-noteworthy actress cornered Mitch on a terrace at the very moment a swarm of photographers happened by, affording some rather staggering news-photos of one Robert Mitchum leering down at an over-lush, half-clad young female.

The leer was unquestionably Mitchum’s, the one he was born with, but the circumstances were absolutely beyond his control. Asked to pose for a publicity picture, he had agreed amiably and without any inkling that the girl involved planned to shuck the upper portion of her costume. Later, pressed for an explanation, Mitchum gave reporters a statement which should go down in the annals of history with those of other doughty warriors—of one kind or another. “My back,” he said laconically, “was to the sea.”

Typically, he bore the girl no animosity, though he thanked his stars that Dorothy, his wife, was along on that sightseeing tour of the Iles de Lérins. Dottie saw some sights, all right. At least this time she knew that the mischief her husband was in was not of his own making. Of the misguided actress Mitch said indifferently, “She was all right. She said that she had been trying to get to Hollywood for three years and figured that this was the only way she’d ever make it. Afterward,” he added with the fleeting, wry grin so typical of the man, “she said she hoped she hadn’t caused me any trouble!”

It was too bad, someone said, that it had to happen to him, of all people. The big guy shrugged and spread his hands, palms up. “Who else?” he asked simply.

In those two words he said a mouthful of wisdom learned the hard way. If the same thing had happened to George Murphy, who winced at Terry Moore’s ermine suit, or Ronald Reagan or a dozen other staid Hollywood citizens, there would have been no international incident. With due local indignation and apologies to the distinguished gentleman so embarrassed, it would have died aborning. There were, in fact, a number of celluloid celebrities present at the Cannes Festival before Mitch arrived, but none had his exploitation value, as Miss What’s-her-name well knew. She has since sunk back into the anonymity from which she briefly emerged, having gained nothing for herself that she could sensibly want. Unless for reasons of her own she cherishes the enmity of Louella Parsons, who is without a peer in her struggle to keep the name of Hollywood clean.

Any attempt to whitewash Bob Mitchum would be a farce. He is loaded with human failings, even some of the common garden variety. He’s as lazy as a three-toed sloth. If he holds still for an interview, you can bet that otherwise Dottie would have had him painting the patio furniture, and he has simply chosen the lesser of two evils. Getting him to talk is like pulling teeth—and once he is started, the experience can be as painful as pulling teeth to the uninitiated listener, since the nature of his eloquence would raise hair on an egg.

He’s painfully honest, which can also be defined as disastrously tactless. Once, when he was beset by about as much trouble as a man could find, Mitch declined to meet the press. Although he did so upon the request of his studio and the advice of sager heads, he was nevertheless awarded the Hollywood Women’s Press Club “Sour Apple” for being the most uncooperative actor.in Hollywood. In the true spirit of Lord Chesterfield Mr. Mitchum immediately sent the ladies a telegram, to wit: YOUR GRACIOUS AWARD BECOMES A TREASURED ADDITION TO A COLLECTION OF INVERSE CITATIONS . . . WHICH INCLUDE PROMINENT MENTION IN SEVERAL ‘10 WORSTDRESSED MEN’ LISTS AND ONE SOCIETY COLUMN’S ‘10 MOST UNDESIRABLE MEN GUESTS’ LIST, WHICH HAPPILY WAS PUBLISHED ON THE DATE I WAS MADE WELCOME AT THE COUNTY JAIL. Women scorned are traditionally to be reckoned with—but again, this was Mitchum, which puts an altogether different light on things. They not only forgave his irony; because of it, they recognized the fact that he needed this final slap on the wrist like a hole in the head. He has friends and fans among them to this day, stubborn, uninhibited and tactless as he is.

He doesn’t like phonies and doesn’t hide it, which means that he has made his share of enemies in Hollywood, and he never met an oddball who didn’t strike a responsive chord in him. If you ever saw an actor holding a calm, rational three-way conversation with a two-headed monster, the actor would have to be Robert Mitchum. What he looks for in people is his own little secret, but he finds it in some pretty remarkable characters. As a matter of fact, this—Bob’s choice of friends and the amount of time he spends with them—has been the only public issue of his marriage. Even his severest critics can’t contrive anything more intimate. Let’s face it: old Mitch, who makes the red corpuscles of grandmothers stir around like a hill of ants, is a one-woman man. He fell in love with one girl, Dorothy, and married her—and that’s it. She and the kids, Jimmy, Chris and Petrine, hold the meaning of life for Bob Mitchum. On that score, at least, he isn’t mistaken; he knows how it would be without them.

After years of yes, no and maybe, things are beginning to groove for Mitchum careerwise. He’s busier than ever before, higher on the popularity polls. And now, he has to put up or shut up on the score of acting. Stanley Kramer has signed him to play the lead in Not As A Stranger, which is certainly the dramatic plum of the year. Moreover, with Paul Gregory, Mitch has invested money of his own in the screen rights to Night Of The Hunter,in which he will portray the most hackle-raising villain to appear on the American scene in many a year. In both pictures he’ll either have to act up a storm or start thinking about one of his earlier professions, like selling shoes. While he’s waiting, he’s on loan-out to Wayne-Fellows Productions for Track Of The Cat and is also scheduled to be reunited with Susan Hayward in The Untamed at Twentieth Century-Fox.

On the face of things he ought to be happy as a clam—but you never saw a more miserable guy. He’s behaving, he’s working hard, and he ends up with an old, familiar companion: trouble. “I’ve gotta get sued,” he said sadly. “If the picture I’m doing with Duke comes in on schedule, I’ll lave fifteen days left on my contract with RKO, and they’re committed to lend me to Fox. If I don’t finish the first picture, Wayne-Fellows sues me. If I refuse to go on loanout for the second, RKO sues me. If I do go on loanout for that one, Stanley Kramer sues me for a million dollars because Not As A Stranger doesn’t start on schedule. And—isn’t this a pistol? —if I don’t meet the production date on Night Of The Hunter, I have to sue myself! That’s right. Paul Gregory and I, as co-producers, have to sue me, as the star, for failing to meet my commitment. We have too much money tied up in it to do anything else.”

What does a guy do in a case like this? Mitch’s shoulders gave a familiar, characteristic roll. “Take them as they come,” he said. “My first impulse was to say, ‘I’m not making any pictures until all this blows over,’ but I have to work. I have four families to support.”

He brooded a moment or two, then the corners of his mouth curled in a wicked grin. “Of course, there is something I could do; I could be so insulting to one of my future leading ladies that she would go to her boss in tears and say, ‘I refuse to make a picture with that uncouth boor!’ Maybe I’ll do that.”

But you knew he wouldn’t. Like all the rest of the problems, he’d take them as they came.

THE END

—BY TONI NOEL

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1954