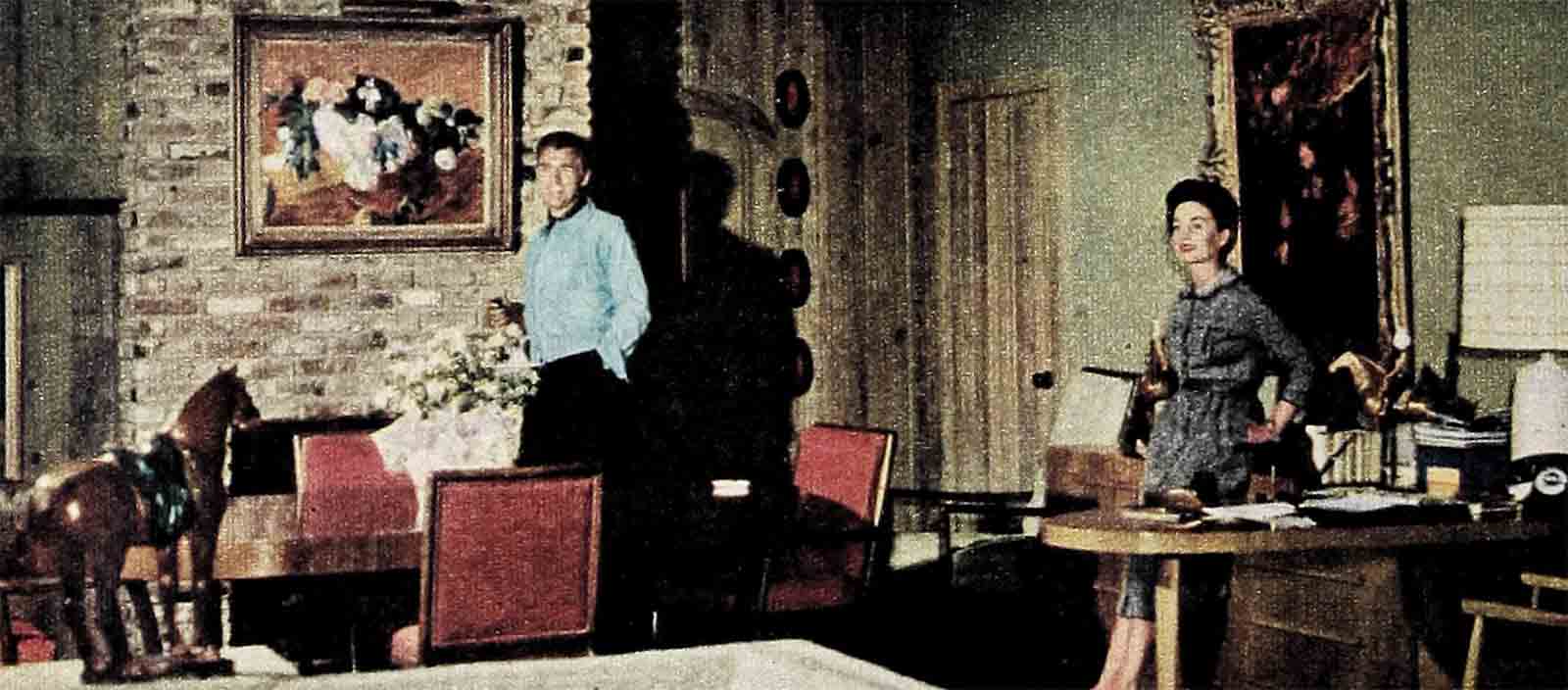

A Doll’s Life With A Guy—Jean Simmons & Stewart Granger

High on a Hollywood hill in a rambling brick and glass house are two oil portraits. They hang side by side and are of the same person—and yet they are of two people. One is a mature, sophisticated actress and the other is a tousle-haired leprechaun, leaping whole-heartedly into all of life. Both portraits are of Jean Simmons and both are true.

About ten years ago Vivienne Walker, one of England’s most in-demand hairdressers, was working furiously at 6 A.M. getting her stars ready for production call. A knock at the door sent her scurrying impatiently to answer. Opening the door, she received a huge snowball smack in the face with the compliments of sixteen-year-old Jean Simmons.

“That brat had been ‘following me around for two years,” Vivienne recalled fondly. “All day I bided my time. It was Jean’s first day on the set in a grown-up part. She was wearing an evening gown, was given a chair with her name on it and played the whole day with complete dignity. That night as the cast passed by saying, ‘Good night, Miss Simmons,’ she turned her innocent eyes on me and said brightly, ‘You ready to go now?’

“Yes!” answered Miss Walker grimly. She quietly and efficiently tripped the sedate Miss Simmons, grabbed her legs and hauled her backside flat down the long corridor, down the outside stairs and rubbed her face in the snow. Between giggles and snow, Jean mouthed, “Stop it. You’re hurting my dignity!”

About nine years later, Jean snubbed out her cigarette resolutely. “Don’t let me have another,” she admonished Vivienne. “I’ve got to stop smoking.” Thirty minutes later on the set of “Désirée,” Jean commanded, “Vivienne, give me a cigarette.”

“You can’t have one.”

“I can, too.” Jean reached over, snagging a cigarette from Jo Parra, her stand-in. She got it as far as her mouth. Miss Walker promptly yanked it away and stepped on it. “We agreed a half-hour ago you were not going to smoke!”

Horrified observers pulled poor little Jeanie behind the flaps and, commiserating about “that awful woman,” proffered cigarettes. With a gamin grin, Jean protested, “But I don’t really want a cigarette.” She and Vivienne sat on the set, laughing helplessly while the bewildered sympathizers smoked uneasily.

Same set; same cast. Jean and Vivienne played a beautiful mock scene of “this is the end—never darken my door again.”

“I’ve had about enough of you!” from the lovely lips of Simmons.

“I’ve had enough of you!” from the unsung actress, Vivienne.

“Go!”

“Gladly!”

A startled visitor raced for the nearest phone to relay same to his favorite columnist. He had his finger on the dial, when he stopped stunned. Both girls were howling with delight.

On a hot, dusty location with Bob Mitchum, Jean watched with envy while the crew shot off water pistols at each other. The minute the director yelled “cut” and they were through for the day, Bob and Jean were in the middle of the aquafied gun-slinging. Bob found a hose and turned it on Jean. She grabbed the hose, whirled around and accidentally turned it full on the producer of the picture. She suddenly looked like a ten-year-old caught with her hand in the family till. She practically curtsied as she mumbled, “Sorry, sir,” and fled, drenched, as if expecting to be chased and spanked.

Jean’s madcap sense of humor has changed only from the boisterousness of early youth to a sometimes subtler approach to finding fun in living. To Jean, each day, indeed each hour of the day, is jam packed with the possibilities for being happy. She is starry-eyed about living and it gives her the effervescent look of a pixie getting ready to happen.

Leprechauns, however, have many more qualities than humor. Considered “the good little people.” Jean answers that description, too, in loyalty, sensitivity to others, a childlike ability to love completely and a deeply ingrained shyness.

In the loyalty department, you will notice that she adored Vivienne Walker years ago in England—and that Vivienne is still with her. When Jean came to the States, she persuaded Vivienne and her husband to pioneer with her. Much to their dismay, they found that she was not permitted, due to American union rules, to be Jean’s hairdresser over here. The struggle still continues to overcome the obstacle, but in the meantime Vivienne is Jean’s secretary, proxy mother and dear friend.

Jean’s sensitivity to others is constant and shines like a light bulb. The only times she has been known to draw herself up to her full height (five feet four) and startle everyone with her strength and determination were for others.

The crews love her. She has the un-usual ability (for a star) to respect anyone who does a good job—be he actor, carpenter or janitor. She is, in their terms, a trouper. She never keeps them waiting on a set and she’s where she should be at the right time. She does not go in for histrionics off-camera. While at RKO, she had a morning ritual. Walking on to the set, she would go right over to the catwalk, climb into the rafters of the studio and have an A.M. chat with the electrician who welcomed her with delight from his lonely perch. A few years later, she walked off the “Guys and Dolls” set at Goldwyn’s and ran into the same electrician. “Hi, Sarge,’ she called, and they spent some time catching up on each other. She doesn’t forget names because the people she meets are complete individuals to her. She likes them enough to remember.

Liking or loving them, she is constantly aware of the needs of others. She does instinctive, impulsive, generous little things, sometimes shyly, and sometimes so matter of factly she leaves no room for feeling indebted or saying thank you.

Jo, her stand-in was called to work on “Désirée,” four weeks after she had her baby. Jean watched her like a mother mothering a mother. The CinemaScope lights are hotter than any of the others and Jean watched for signs of weariness. Suddenly she would jump out of her chair, go up on the set and say casually to Jo, “Would you go somewhere else for a while? I want to stand in for myself and get the feel of the set.” And Jean would stand, getting “the feel of the set” while Jo rested.

She is not afraid to take the physical or emotional brunt of doing something decent. While still in England, Vivienne Walker was in charge of the Christmas party entertainment for an English veteran hospital. She was in despair. The stars were quite willing to donate money, but, because it was the most tragic of all hospitals, they couldn’t bear to see the boys without arms and legs. Vivienne turned to Jean. As with all of us, she had an instinctive desire not to face the aftermath of war. But she said, “I’d go, honey, but I can’t entertain them.” Vivienne, who was frantic by this time, suggested she serve them tea, act as their hostess.

She went, and those boys, most of them carried to the recreation room on stretchers, loved her.

Watching Jean’s emotional antenna in action is a sight to behold. One girl on the set of a new picture heard the typical rumor that accompanies every star, “She’s difficult.”

On the first day of shooting, the girl watched the blue-jeaned Jean walk by her in doubt and wonder. Suddenly, for no apparent reason, Jean wheeled around, came back and embraced the startled girl and, with a warm smile, went merrily on her way. From that day forward, the girl was her slave.

Her sensitivity to others is strongly tied to a deeply ingrained shyness and sense of inferiority. She honestly is unaware that she is a star. She has admiration and fanlike interest in other stars. Having lunch at the M-G-M commissary the other day, she was as excited as a child. “Look who just came in.” She ogled the stars like a kid at her first circus. She still carries her now-famous autograph book. It was a charming sight to see surprised stars, in turn delighted to meet Miss Simmons, appending their signatures to her autograph book.

Now is the time to go into the paradoxical personality of Jean. Signing her book, those stars were well aware of her stature as an actress. They knew that she came to the States in 1950 with four international awards and the title of Britain’s most popular star tucked in her hot little hand. They also knew that at eighteen she had rocked Shakespeare lovers and others alike with the greatest interpretation of Ophelia in “Hamlet” to date. Before she was twenty-one, she had handled both Shakespeare and Shaw brilliantly and carved her own special niche in the annals of theatre. How to reconcile this admiring pixie and mature actress?”

The paradox is simply explained. The minute Jean steps before the camera she becomes the mature actress of the other oil portrait. Two loves has Jean. Her husband, Jimmy, and acting. When working on a picture, she lives, eats and breathes her profession. She knows her craft, loves it and is a willing slave to it. She has that intangible but all-important ability to become the character she portrays. She can, according to the need, be queenlike, alluring, insane, speechless or distraught. Her face and figure can report with startling realism the mood of any script. While on-camera she is a breathtakingly different woman. When off-camera, her inner excitement and enthusiasm is contagious. She loved working on “Guys and Dolls.”

“I just can’t wait,” she exclaimed while making the picture. “I come down to the studio even when I’m not working just to be a part of it. I haven’t felt this wonderful spirit on a picture since ‘The Actress’ and before that, ‘Hamlet.’ It keeps you keyed up all the time. With Joe Mankiewicz directing and Mike Kidd on choreography and Harry Stradling on camera, plus Frank (Sinatra), Marlon (Brando), Vivian (Blaine) and Sheldon (Leonard), and all those crazy, wonderful Guys wid de Brooklyn accents every day is a riot.

“I play Sarah, the Salvation Army lass, in this,” she continued. “And I’m singing my own numbers. I sang when I was sixteen and they suggested I work on my dramatic acting. But Mr. and Mrs. Goldwyn and Frank Loesser were auditioning six girls to find one that would match my voice for dubbing. So I had to sing a little to show the girls. Frank and the Goldwyns looked at each other and decided I could do the singing myself! I was thrilled—and scared at the same time. I wake up in the middle of the night singing those songs. But I guess I’m doing all right.”

Later, the casual phrases “I wake up at night singing” and “I guess I’m doing all right” took on their real meaning. She stood nervously in front of the mike in the rehearsal hall. Drying her moist palms on the legs of her blue jeans over and over, while she waited for her cue. On cue, she closed her eyes and put her whole being into singing the song, “I’ll Know.” A surprisingly good, sweet voice put new meaning into the lyrics known throughout the nation. Jean, the actress, was completely absorbed in the moment. Listening to the play back, she became very quiet and deeply distressed; she had goofed on one note. She had not done it exactly right. There was no doubt that the Hollywood hills would ring with “I’ll Know” that night.

And the Hollywood hills would be lonely that night. For Jimmy (Stewart Granger) was still in Pakistan making “Bhowani Junction.” Home without Jimmy is intolerable for Jean. They love their home because it means togetherness. When one is gone, it becomes a house—a dead thing. If it weren’t for the dogs and cat, Jean would go out even more than she does when Jimmy’s away. But the two poodles, Young Bess and Old Beau, and the dog-dog, Me, Too, plus the Siamese cat, Tracybert, give her a reason to at least check in and love them. She climbs into her Jaguar (soon to give place to a Mercedes-Benz sports car) and pops off to the Bert Allenbergs or Liz and Mike Wilding, or goes dancing with a friend of both Jimmy and herself. A columnist reported during this period, “Jean Simmons seen having dinner quite openly with a top star.” Which, leave us face it, is quite the nicest day to have dinner—with a top star.

The last time Jimmy went away on a picture, Jean lost ten pounds because she hates to cook. So now they have a staff and Jean eats regularly. But on the staff’s night off, Vivienne and Jo take turns coming up to stay with Jean. It is a lonely hilltop.

When Jimmy is home, all is different. Home is a place to rush back to. Jean feels she is a very lucky woman. Most men would swear that Jimmy was a very lucky man. For she has that magnificent quality of understanding that most men devoutly hope for in a wife—and quite often don’t find. Jean’s sensitivity to others starts with Jimmy. She matches his mood. She knows when to be helpful, when to be silent. She just knows plain when and what to do with Jimmy. She knows (and much to his embarrassment the public is finding out) that his bark is much worse than his bite. That when he stands strong and forceful against or for something, it is because of his deeply imbedded old-fashioned principles. She understands his impulsive, generous nature that makes him a sucker and a softie on many occasions. The things he does for others he wants kept quiet. His embarrassment will be acute when he reads in print of his steady habit of sending boys fresh out of the service to his own tailor and picking up the check.

“Woman,” he roared at his other half, “you’ve got to train that cat. It’s sitting here on the coffee table eating the fern.”

“Yes, sir,” answered his dutiful wife and promptly swept Tracybert to the floor. Five minutes later the cat was solemnly munching fern on the table. The master rose in wrath. “You’ve got to show ’em who’s boss.” Whereupon he grabbed the hapless cat, drew back his hand ferociously and tapped it gently on the bottom and took it in the living room. He did not look at his wife who had watched his demonstration of mastery with innocent eyes. Ten minutes later the Grangers were forced to change their positions on the divan. It was difficult for them to continue watching television with the cat and the fern in the middle of the coffee table.

Many writers and commentators have created confusion about the Grangers’ marriage by constant speculation as to why it lasts. At first, the Grangers were incensed, then hurt—now resigned. The basic elements of their marriage are solid. First, they love each other, which is usually considered fairly important. Second, their personalities blend beautifully. Third, their senses of humor match. Fourth, although not running true to form for the so-called average marriage, they give to each other exactly what each needs.

Perhaps Jean’s innate sense of happiness comes from the simple fact that she loves and is loved. She is cared for, thought about and planned for, and every woman blossoms under that kind of treatment. She is almost apologetic about the many things Jimmy does that she feels should be her duties. Yet, he does them better and they both like it that way. He decorated their beautiful home. “I suppose I would buy new drapes,” Jean said doubtfully, “if these fell off the wall.” He used to do all the cooking; now he cooks when the staff is out. “I can,” she said hesitantly, “cook the dog food and cut up the cat’s liver . . . I mean the liver for the cat. I tried to cook for Jimmy once and he suggested I concentrate on my acting. He plans the food and manages the house completely. I sign checks when he’s away,” she points out hopefully. “Everything about the house is so well organized that I become completely lazy when I’m not working. If someone doesn’t wake me up, I’d sleep forever. There’s just nothing for me to do about the house.”

Jimmy seems perfectly content to have the balance of choice and decision in his hands. They have explored and tested their individual abilities and are delighted with the outcome. Jean is free to remain a happy sprite filling her home with warmth and laughter. That’s the way Jimmy likes it. Even when she has a desire to be sophisticated and elegant, Jean can’t keep it up for long. Dressed to the teeth and feeling trés gay, she will invariably trip over something and collapse in hilarity. She never looks where she’s going, which makes it tough on sophistication. She also has the inelegant habit of kicking off her shoes anywhere, any time.

An endearing quality, which all men adore, is her pleasure in listening to Jimmy. “My idea of a heavenly evening,” she will say dreamily, “is to have Jimmy broil huge steaks for Spencer Tracy and the two of us. After stuffing ourselves on his good cooking, I curl up in front of the fire and listen to man talk. They fight a good fight. It’s fascinating to listen to two intelligent men argue the world apart. And one automatically takes the other side, so it’s always a good scrap.”

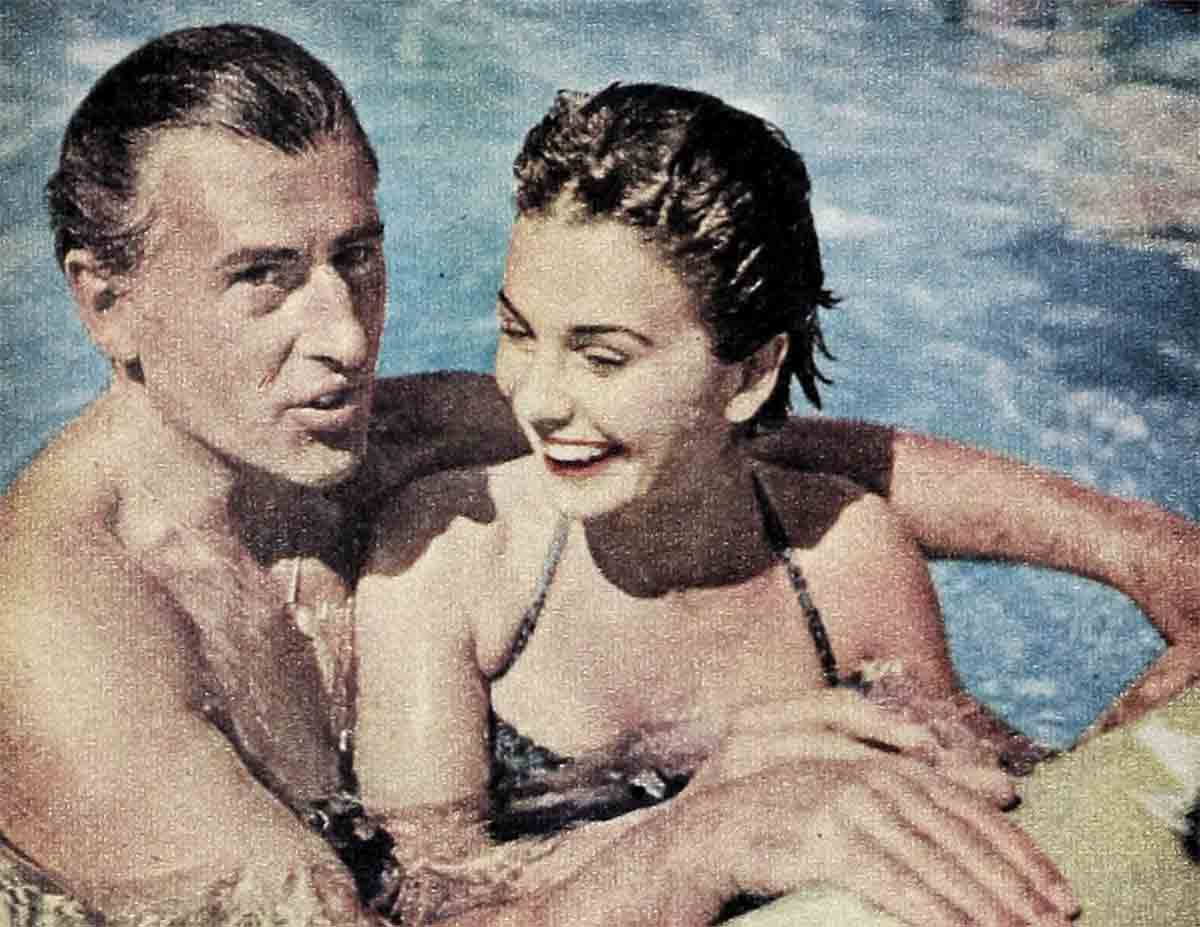

On the other hand, she is a lively and captivating hostess when they have a group in. They seldom invite more than ten good friends. Whether a barbecue, swimming party or sit-down dinner, Jimmy does the behind-the-scene planning and Jean stimulates the party. Be it at home, an elegant party or a baseball game, Jean has a wonderful time wherever she goes. She is now an avid baseball fan. “Three Americans tried to explain baseball to me at my first game. Finally, Jimmy explained it completely in five minutes. I’ve loved it ever since. We went to a party Laraine and Leo Durocher gave for the team before the Cleveland game this spring. Dusty Rhodes was the life of the party and the party went on and on and on. So the next day, when Leo put Dusty in to pinch hit, everybody who’d been with him the night before groaned. Did we feel silly? He hit a home run!”

“See this gun?” she said with a sudden switch of interest. “It’s the twenty-two I practice with every Sunday. I sent Jimmy my target card yesterday, seven bull’s-eyes and three very near misses out of ten shots. Not bad, huh? The next time Jimmy and Colonel Dean Drummond, the white hunter, plan an African safari this child will be ready to join them!

“I wonder,” she speculated in another quicksilvered change of thought, “what Jimmy will bring me this time.” His surprise packages on his return home from picture locations throughout the world have been memorable moments of tenderness and affection. On one trip to England, he had copies of the only remaining picture of her father made up in every size. Jimmy knew that Jean had adored her father. He died two months before her initial success in “Great Expectations.” “If only Father could have been here,” she said wistfully at the first showing of the picture. There is still a touch of pain in her when she brings out his picture and proudly shows it to friends.

Another surprise package was Me, Too. Jimmy carried him across a continent in the pocket of his great coat to hand to Jean. Jimmy’s usual attitude of “if you can’t housebreak ’em, rub their noses in it” took a nose dive with Me, Too. He followed the tiny puppy around the house like a doting father, remonstrating gently and clucking careful disapproval as he cleaned up the trail left by the untrained pooch. Jean followed these gyrations with amused maturity and wisdom.

For basically mature and highly intelligent, she is. But she has learned, or perhaps was born with an important ingredient for living. She accepts the pleasure of enjoying life—instead of probing it. She anticipates each day with a light heart. Yet she is fully aware of the pain, sorrow, unfulfilled needs and heartaches around her. She has experienced her own but keeps them carefully hidden within herself. Jean has by-passed the trap of letting maturity make her staid and sedate. Instead she holds maturity in abeyance for use when necessary and allows herself the joy of being herself. But people who would ruffle the tousled hair of this pint-size pixie in blue jeans as they would a charming youngster should think twice about the enigma they are talking to.

Jean was standing on the edge of their hill. The rifle in her hand lazily made a wide arc encompassing the whole of Beverly Hills, Hollywood and Los Angles as the target. “It used to be that Jimmy and I would end up on a farm in Africa. Then it was Spain. Then Italy—then Spain again. Now it’s Switzerland.” Jean’s hazel eyes suddenly brightened with a mingling of mischief and maturity, “It could be that we’ll end up right here. It could be,” she repeated as a dawning pleasure at the possibility struck her. “Right here we’ve got everything we need to be happy.”

The dogs and the cat bounded around the house and slid pell-mell into her open arms. She stood with a dog and a cat on either arm, staring down at the town she had learned to love. The only thing she lacked was Jimmy and he’d be home soon. Looking the picture of content, she nonetheless had the rifle close by—and she would continue practicing. It just might be that an African safari was in the offing. She would be ready.

High on that Hollywood hill in the rambling home are two oil portraits. They hang side by side and are of the same person—and yet they are of two people. For one is a mature, sophisticated actress and the other a tousle-haired leprechaun leaping wholeheartedly into all of life. Both portraits are of Jean Simmons and both are true.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1955