Life Begins For Margaret O’Brien

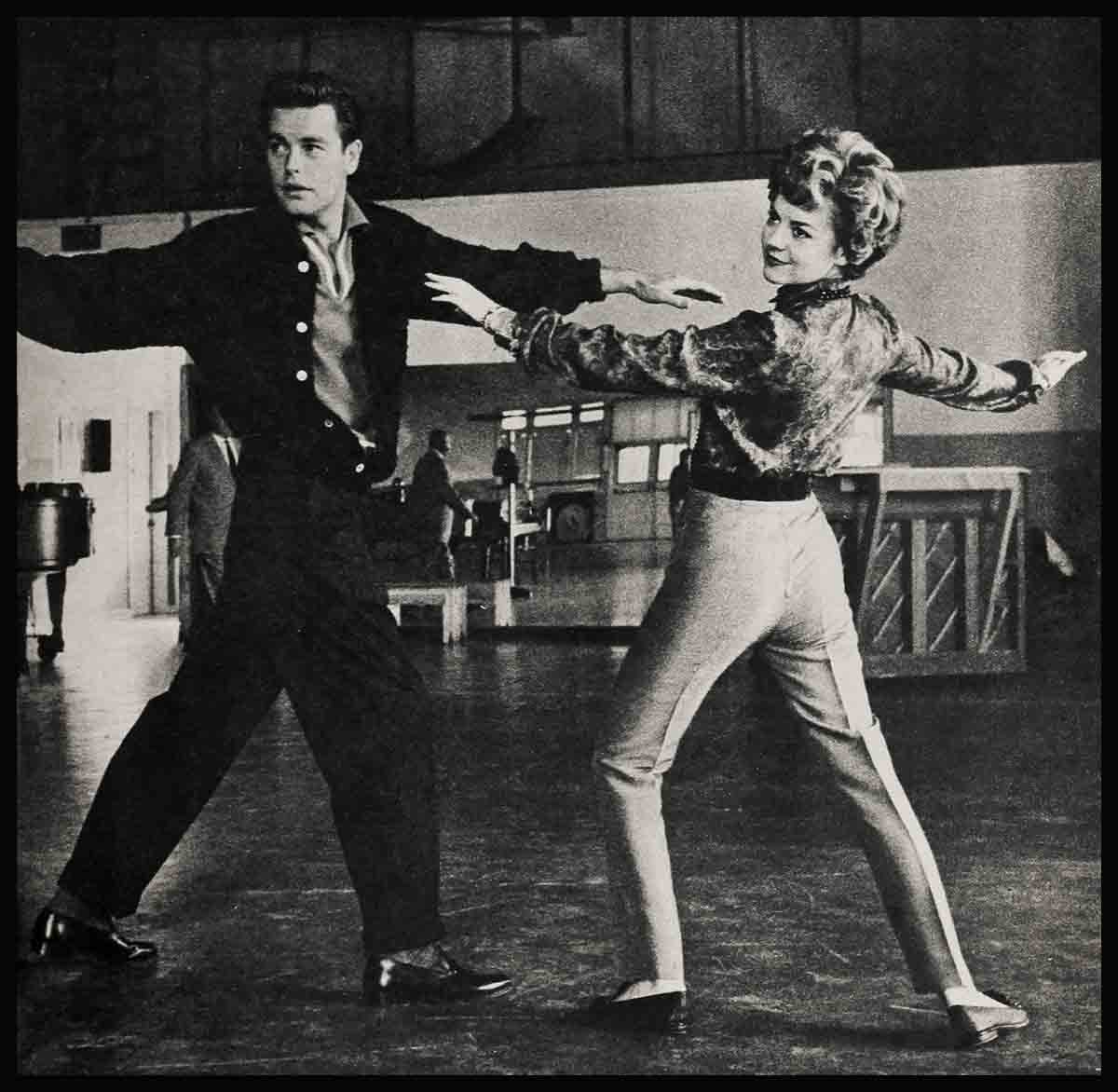

It was just another morning recently when another picture started at another Hollywood studio. But for Margaret O’Brien the day held a special promise. She was up at 5:30 and at the RKO gate by 7. The cop checked off her name without a glance of recognition. Five years is a long time to be out of pictures.

Besides, maybe she’d changed. She sat in a boxy, portable dressing room waiting for the first scene of her comeback picture, Glory—and it was a tough one. She was to cry. She’d never had much trouble crying. She used to ask her directors, “How do you want the tears—inside or out?” But now a brief flicker of anxiety crossed her pretty, quiet face and centered in her expressive sherrytinted eyes. The middle-aged woman with her noticed and averted her gaze. “Come on, Mother,” urged Margaret. “Talk to me—you know, like you used to.”

But her mother replied, “I can’t, I’m afraid. Not any more.” So she walked out alone when they called her into the scene. The director who watched her closely remembered something Lionel Barrymore said: “She’s the only actress in the world, outside of my sister Ethel, who can make me pull out my handkerchief.” The director’s name was David Butler, and he has been around Hollywood a long time. Once, his specialty was directing kid a actresses. Somehow he’d skipped this kid until now, but he knew what to say. When the scene was over he put his arm around the dainty five-foot girl. “It was great—just great, honey. You’re the same wonderful kid—the same Margaret!” But that wasn’t quite the truth.

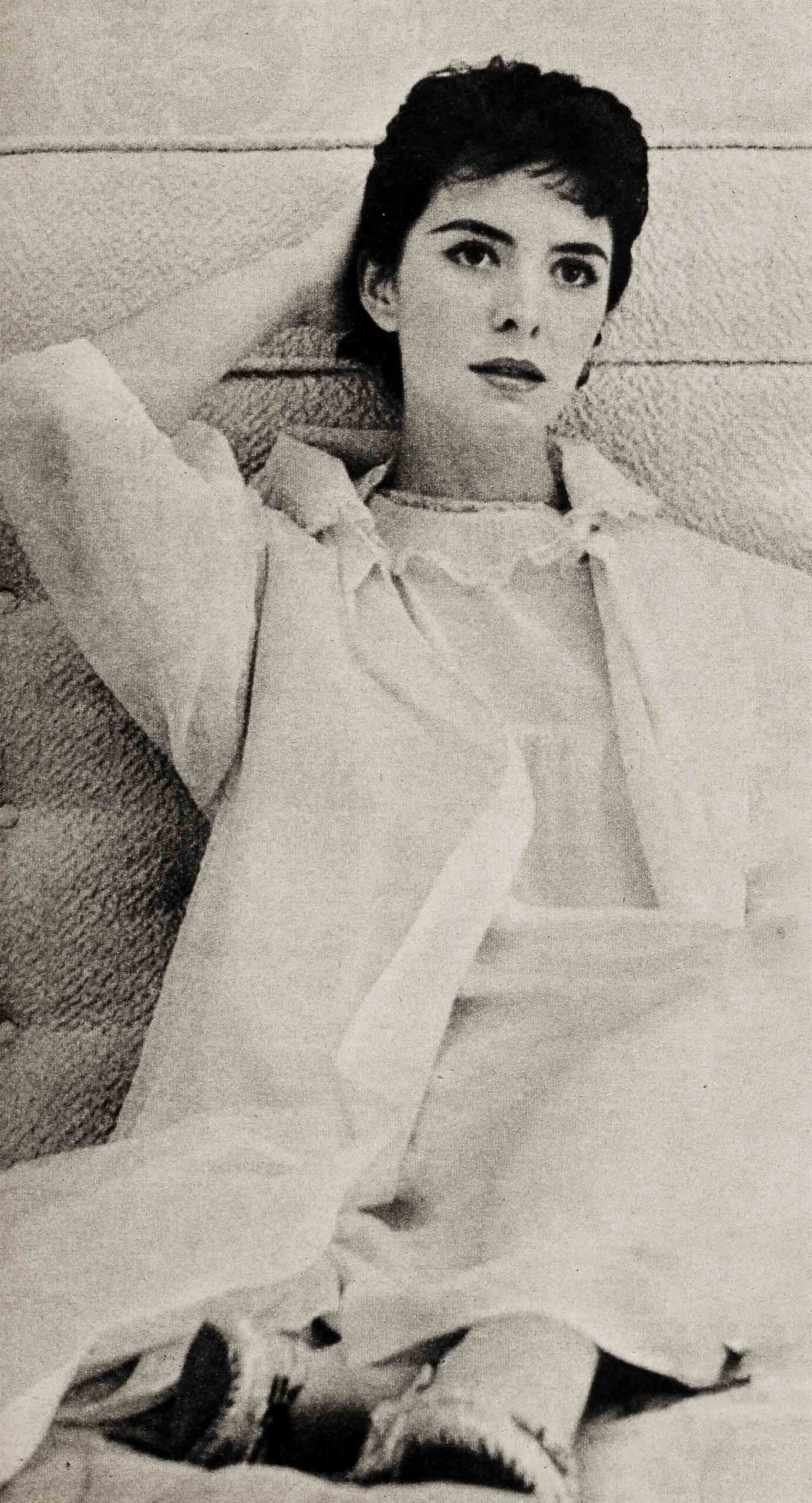

Margaret O’Brien obviously retains the same amazing talent which made her Hollywood’s wonder child of the forties. But today she no more resembles the fabulous pigtailed moppet of that lost decade than a butterfly suggests a caterpillar. Today Maggie’s a young lady, and a very lovely one indeed—but a lady with a problem. Briefly, she faces creating a new life for herself, a new career and—to make both a success—a new maturity. For far too long pretty Maggie has been holding back tomorrow because she couldn’t forget her wonderful yesterday.

As a result, at eighteen Margaret O’Brien finds herself at least three years behind her age and on the spot to catch up. Only last year she had her first date with a boy, and only a few weeks ago her first without her mother by her side. As recently as last January 15, on Maggie’s eighteenth birthday, Mrs. Gladys O’Brien had to get on the phone and rustle up a date (Tab Hunter) for her coming-of-age dinner party at Chasens, because her daughter didn’t know whom or how to ask. Although Maggie’s been eligible to drive a car for over two years now, she learned how only two short months ago. Just this past May—halfway into her nineteenth year—did she graduate from high school, at which formality she knew no one else in her class. Only in recent weeks has Maggie conducted a press interview without her mother, shopped for a dress, made a business decision, fallen halfway in love or fixed herself a sandwich. And she parted with her long, girlish tresses, never cut before in her life, just a few weeks ago, but only after her agent handed her an ultimatum: “No haircut—no parts!”

All of this is unique even in Hollywood, but still understandable. Because as far back as Margaret can remember she was no normal growing girl but a boxoffice treasure wrapped in cotton batting. Nonetheless it poses a crisis in her life today as she tries the near impossible—to be as great as an adult as she was a child. To pull that off Maggie must measure up to her present and break with her past. On that challenge hangs her future. And for her it’s a pretty large order.

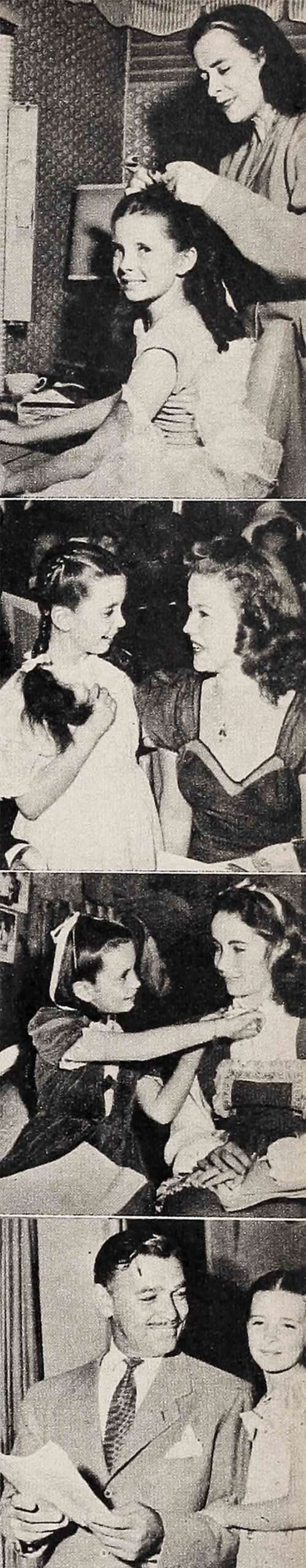

Because Margaret O’Brien has been Mama’s girl ever since she was born in Los Angeles nineteen years ago come next January. She never knew her father, Larry O’Brien. A daring circus rider, he was killed in an accident in Mexico City a few weeks before she arrived, a fragile baby weighing only three and a half pounds, but not insignificant. In fact, the obstetrical nurse ventured a prophecy as she deposited the tiny bundle in Glady’s O’Brien’s arms: “Here’s a little lady who’s destined for big things.” Gladys never forgot that. It fitted right into her dreams. She was a circus dancer herself and had kicked her legs up until an hour before her baby was born. Her ancestors had been entertainers in Spain.

With that heritage and maternal resolve, it’s not surprising that with Journey For Margaret the journey of a very uncommon child through a very uncommon childhood began. Margaret O’Brien was only four when she posed for magazine covers, just five when she made the appealing picture that made her a star. It isn’t too strange that Margaret finds herself faced today with a very uncommon adult problem. If the memories of her childhood glories cast a shadow on her future, it’s because she’s afraid she can never match them. Yet it’s also understandable why her mother says now, “If I had it all to do over again, ’m not sure I would let her be a child actress.” Gladys O’Brien can see, if Margaret can’t yet, the handicap this has placed on her daughter’s development. What is harder to figure is how a critic could write at the height of Margaret’s kiddie fame: “Her face is a perfect mirror for the sharp, deeply felt emotions of childhood.” Because all the while Margaret had no real childhood in the normal sense of that precious word.

But he was strangely right. There was no one like her. Not even Shirley Temple had been able to tug such smiles and tears from a world-wide audience, as Margaret did in Journey For Margaret, Lost Angel, The Canterville Ghost, Meet Me In St. Louis, Three Wise Fools and the parade of pictures that are still pointed to as classics of juvenile acting. She was a hit from the start; she never had a bad review. Charles Laughton called her “the finest actress in the movies,” and Lionel Barrymore, watching her perform, muttered unbelievingly, “If Margaret had lived two hundred years ago they’d have burned her for a witch!” She still treasures a pearl and diamond brooch the great Barrymore gave her, one his famous grandmother, Ellen Drew, had worn. “Until now,” he said as he bestowed it, “I’ve never met anyone else fit to wear it.”

There’s no indication whatever that Margaret rebelled at any of this or was dragged by her mama into anything she didn’t thoroughly enjoy. On her sets she slipped into her scenes with the delight of a child playing make-believe. Never an obnoxious tyke, still she revelled in her precocious importance and in those days often exhibited spunk and a wicked sense of humor. When Captain Clark Gable of the Army Air Force came back to Hollywood on leave, spied her in the MGM commissary and asked who she was, said Margaret, “Mister Gable doesn’t get around much, does he?” Louis B. Mayer, boss of the studio, asked her once to name what she wanted for a present and Margaret came back cannily with “Busher!”—then the pride of Mayer’s racing stables and worth around $150,000 on the hoof!

So it’s no wonder that everything about those glorious days is still bathed in rosy hues for Margaret O’Brien. Life was a juvenile ball, on the set and off. General Marshall wrote her fan letters. Harry S. Truman gave her a Presidential Citation in person for helping sell $17,000,000 worth of war bonds. Eleanor Roosevelt asked her to lunch. On a tour of Europe Prime Minister Atlee entertained her at dinner at 10 Downing Street, and she sat in the House of Commons before Queen Elizabeth did. The Pope blessed her in a private audience. She.even dragged her mother to Algiers and visited the Casbah, just like Hedy Lamarr, even though they got scared afterward and hired a guard to stand outside their hotel room door—and then couldn’t sleep a wink, afraid of the guard!

By the time she was twelve it would be hard to think of much that little Margaret O’Brien hadn’t collected in world-wide adulation, honor and fame. In addition, she had climbed to the top ten of Hollywood box-office attractions, collected a special Academy Award and earned $5000 a week. But there was one important thing she sadly lacked—social contact with her own generation.

Because all this time, while Margaret’s public world was wide, her private one was painfully narrow. She grew up, but she didn’t “wise up,” as the kids around her would put it. Until the night, this past June, when she donned a white cap and gown to officially graduate from University High in West Los Angeles, she had never been inside a school, public or private. She had only tutors—women tutors. The only club she ever belonged to was the Brownies—and that was an “honorary” membership. She never shared thrilling secrets with girl chums or had boys frisk around to tease her. Kids outside her buffered world loomed as menaces, who mobbed her in public and tried to cut off her pigtails for souvenirs. Once her mother snatched away a pair of scissors on the brink of that desecration. She never had a sweetheart. All Margaret’s girlhood crushes were movie stars—Burt Lancaster, Clark Gable, Laurence Olivier—idols as unreal as she was.

“I was always somebody else instead of myself,” Margaret recalls wistfully, and that was too true. She could be somebody else so realistically that often she confused herself. Once she informed an examining county health officer that she’d had scarlet fever, thoroughly believing it. She hadn’t—but Beth, the character she’d played in Little Women, did. And sometimes when she did try to be just Maggie, well, that was against the rules.

Loving horses and inheriting a talent for riding, Margaret wheedled affable Wally Beery into letting her ride his spirited horse once on location in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. The horse bolted off across the prairies and it took four cowboys to catch him and snatch Maggie to safety. But after that the taboo went out—no more horseback riding. Only recently has she dared take it up again.

Margaret sublimated her craving for friendship by harboring all sorts of less formidable companions—mice, parakeets, kittens, pups and colonies of dolls. But actually her two best friends were MGM and Mother. Of the two Mama was the closest. Until right now Gladys O’Brien has been protector, playmate, mentor, slave, right arm and very often her daughter’s brain. Mother prepped Margaret for her next day’s scenes every night, then hovered near her on the set. Wherever Margaret traveled Mrs. O’Brien was necessarily, but eternally, at her side. She prepared her food, picked up her clothes where she dropped them (she still does that) woke her in the morning, tucked her into bed at night. When she couldn’t, Margaret’s Aunt Marissa did, so often for one stretch that rumors flew around that she was Maggie’s true parent. The trio lived together until Marissa Bogue left for Paris a few weeks ago, with her husband and eight-year-old daughter, named after Margaret.

But whoever took over, the result was to surround Margaret O’Brien perpetually with an all-feminine directorate and to make her completely helpless and dependent. Today she confesses, “I can’t even make a cup of tea.”

Then all of a sudden Margaret turned thirteen and into the inevitable awkward age. It was no smooth transition for her as it was for Liz Taylor or Janie Powell. With no parts for gangling girls, MGM dropped their great child star. One world was gone—but not forgotten. That left only Mama for Margaret.

To Gladys O’Brien’s credit it must be said that when this happened she tried to do something about it. “I wanted to leave Hollywood,” she has said. “I wanted to take Margaret to New York and put her in school. I felt she needed it; she was too dependent on me. She needed relationships with girls and boys her own age. Besides, I believed we had had all that Hollywood could give Margaret. In New York she could have studied the theatre and by now been a fine young actress. But Margaret wouldn’t leave Hollywood. She couldn’t believe she wouldn’t go on there somehow as she always had. Sometimes I wish there had been a man to tell her what to do and make her do it. Our house needed a man.”

But when Gladys found a man, Margaret acted up pretty outrageously.

If you remember the headlined episode, back in 1949, he was a handsome bandleader named Don Sylvio—and on the record it seems he got a pretty frustrating deal out of the brief alliance. Apparently he couldn’t get past Margaret’s pouts to get acquainted with his new wife.

At the wedding in Miami, Florida, Margaret stained her white taffeta dress with tears, and when reporters asked her if they were tears of happiness or sadness she cried, “Oh, I don’t know—I don’t know!” When photographers asked her to kiss her new stepfather she whirled away in flat refusal. Next morning the bride rode off on a trip to Boston—not with her husband—but with her daughter. Four months later Mrs. Sylvio asked an annulment stating that the marriage had never been consummated, a claim which Mr. Sylvio vigorously denied, adding, “I don’t know what this is all about but I’m not going to let Margaret or her mother make a sucker out of me!”

In the subsequent welter of charges and counter charges, Don Sylvio laid the rift squarely to Margaret’s unwarranted jealousy. “Whenever Gladie and I wanted to go out, Margaret was hurt and sulked,” he said. At night, he revealed, Margaret climbed into her mother’s bed. In September of 1950 Gladys O’Brien won a divorce, charging that Sylvio had demanded $200 a week for himself, a new car, a grand piano, a house for his mother and had declared, “I’m going to handle Margaret’s affairs from now on.”

But whoever did this or said that, Margaret O’Brien came out of the mixup for the first time in her life with an unpleasant portrait—that of an ungrateful daughter who had wrecked her devoted mother’s chance for happiness. Mail swamped her, some taking her side, but a lot calling her brat. In Chicago, one man stamped up to her on the street and hurled, “You bad girl! You ruined your mother’s marriage!” Margaret gasped and ran. Nothing like this had ever happened to her before and the effect was shattering. About that time Margaret was supposed to be the voice of Alice in Walt Disney’s Alice In Wonderland but the job was called off. Her mother said, “All this publicity has cost Margaret thousands of dollars in contracts.” Around this time, coincidentally, Margaret was up for her first bad girl role in a stage production The Intruder. She played a stepchild scheming to destroy her parent’s second marriage. When the parallel to what had happened in real life was pointed up by critics, Mrs. O’Brien was not pleased. But, “I’ve done more to hurt her than she has ever done to hurt me,” she stated loyally.

Actually, few psychologists, in the light of Margaret O’Brien’s life up until then, would have expected her to act any differently. She had only her child acting career—and her mother. One had started to tumble. A rival appeared threatening the other. Unreasoned panic at an age when security is all-important seized her; a mature outlook was impossible. Mrs. O’Brien’s tug between loyalty to her talented daughter and the desire for a life of her own is not hard to comprehend either. But the most significant revelation from it all was this: That while Margaret leaned on her mother and her mother depended on her as much, both were already subconsciously resentful and rebelling.

There were other signs of conflict. Mrs. O’Brien bought the Beverly Hills duplex where they still live. But Margaret was unhappy that her mother owned it. So Gladys O’Brien sold it to her daughter, although she says she could have gotten $18,000 more on an open bid. Gladys wanted to move to New York; Margaret refused. Dresses, hairdos, lipstick, apartment decoration, career plans, etc., etc. became controversial issues. Margaret stayed in her room more and became “harder to reach.” Mrs. O’Brien, it was noted, was often indisposed with headaches, particularly after her upset marriage. And there was the constant tension about Margaret’s money.

Margaret left MGM with a fortune of around $200,000 in government bonds. But under California’s “Coogan Law” (enacted after Jackie Coogan’s parents notoriously dissipated his fortune) it was administered by the courts. Each year she came up for an accounting (and will until she is twenty-one, unless she marries first). Periodically, judges noted that Margaret’s fortune was dwindling too fast. Only last year for instance, one observed sternly that the principal had dwindled $34,623 in the previous two years. Particularly he singled out items to question like frequent trips to New York, where each time expenses had exceeded her earnings. “And what,” he demanded, “is that item of $46 for lunch at Romanoff’s?” At the end he ordered Margaret and her mother to cut expenditures drastically.

The uneasy implication was that Gladys O’Brien was being too free with Margaret’s money. Actually, this was never quite so. Mrs. O’Brien got paid well all during Margaret’s MGM contract for being a movie mama and she saved most of it. Today she has her own money and some comfortable annuities. Yet in the closest of family setups money matters are a not so subtle disturbance. Mrs. O’Brien explained that it was necessary to spend money to keep Margaret before the public and added, “Margaret wants nothing out of life other than to be a great actress.”

At that point, and for too long before, that seems to have been only too true.

At an age when most girls discover the wonders of themselves, Margaret kept on striving to be somebody else. At a time when most girls dream, explore the opposite sex, the world around them, rebel and fashion brave new patterns, Margaret wanted most of all to do the same old thing. At the period when most teenagers are impatient to cast their childhood into limbo, Margaret clung to her golden years.

When Hollywood forgot her—after a teenage Columbia effort called Her First Romance which didn’t set box-offices afire—she toured the East and Middle West in stock companies. Gladys O’Brien went right along, as ever, and so did a tutor. Demure and dainty, Maggie played juvenile roles in road show standbys like Peg O’ My Heart, Smiling Through, Gigi and Kiss And Tell. She was as good a young actress as ever. In fact, after opening in Clare Boothe Luce’s play, Child Of The Morning, one critic called her, “a young Helen Hayes.” The story was the same on radio and TV—in Studio One, Climax, Robert Montgomery Presents, Lux Theatre, Toast Of The Town, and others. She showed no more temperament than a turtle, was so confident and calm that one colleague remembers, “She made everyone else nervous!” She played Juliet to José Ferrer’s Romeo without batting an eyelash. And when she flew to Japan to make Girls Hand In Hand she babbled the whole script in phonetic Japanese although she couldn’t carry on the crudest conversation in that language.

But Margaret came home happily clutching a collection of Japanese dolls.

The fact is that during the years when most girls eagerly grow into women, Margaret O’Brien stayed a child at heart. She clung stubbornly to her badge of girlhood, the long chestnut tresses. She dressed demurely, conversed primly and acted, as one disillusioned boy complained, “as if she’d just stepped out of a convent instead of fifteen years in Hollywood.”

Although she delighted in dressing up and going to night clubs and cafes, Mama was always at her side. She went to Barbara Billingsley’s New Year’s Eve party at the Stork Club but left discreetly before midnight. Boys like Sean Downey (Morton’s son) who danced with her found nothing much to talk about. Her first date was with a handsome young West Point cadet named Dick Bentley. Her mother arranged that introduction, knowing his father. He took Margaret out in New York and asked her up to the Point, but she declined. He didn’t call again. Mrs. O’Brien, curious, asked his father, “What happened?” He grinned wryly. “He says she’s too naive.”

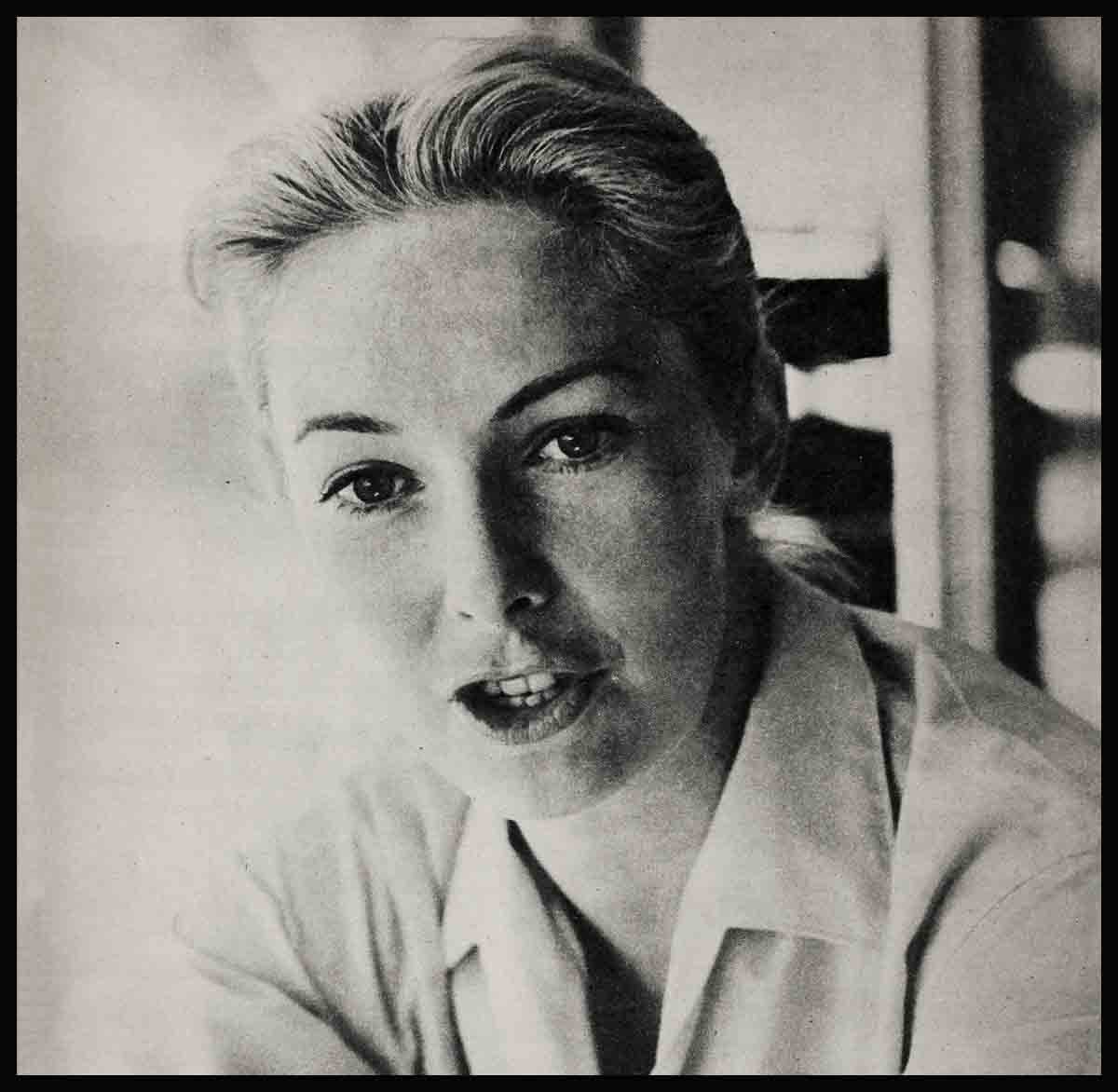

Right now, of course, Margaret O’Brien is too naive, but she’s far from being unattractive. On the contrary, biology has outdone itself in transforming the rather plain little whiffet into a gorgeous young woman. With her burnished brown hair cut in a cute Audrey Hepburn bob, her dark eyes and creamy complexion with a dimple dotting her upturned lips, actually she’s ravishing to behold. There’s nothing wrong with her 32-20-34 figure either. The whole trouble with Maggie’s charms to date is simply that she’s lacked a provocative personality and a touch of adult sex appeal to bring it all to life. If she can just forget her little girl image and let nature take its course she shouldn’t have any trouble at all. Fortunately there are some pretty sure signs that that’s exactly what’s taking place at last.

Maggie still lives with her mother, but the picture isn’t quite the same as it was. For one thing, the phone jingles constantly and, as Gladys O’Brien sighs, “The chatter goes on and on.” A herd of Hollywood stags, apparently just waiting for Maggie’s awakening, are on the other end of the wire—young actors Rad Fulton, Harold Selsen, Richard Davalos (before his marriage), studio technicians Hal Belcher and Dennis Kingsley, to name a few. In fact, the extended courting line sometimes piles up on itself. One evening Maggie stepped out with Dick Davalos to the graduation dinner her mother gave her. When she came home, late date Bob Allen was waiting to take her for her first look at Mocambo. It was also her first excursion without her mother along. “I just locked myself in my room and hoped for the best,” admits Mrs. O’Brien. But she needn’t have worried. When Margaret came home she asked her how she liked the floor show. “Oh,” her daughter came to, “I don’t know. I didn’t notice it.”

But Margaret is noticing a lot of things recently that never absorbed her thoughts before—“Mainly Margaret,” says her mother, “thank goodness!” She spends hours before the mirror testing this and that make-up and worries about her hips to the point of counting calories and taking poundings at Terry Hunt’s. New dresses already pose a closet problem, and undoubtedly will draw a reprimand from Maggie’s court guardians when the bills come in. She goes for very bouffant-skirted numbers, size seven; shops for them herself and sometimes guiltily hides them around the house from her mother. Costume jewelry is another vanity kick she can’t resist lately. She has stacks of gilded bracelets and one hundred pairs of earrings.

Since her driving lessons, Margaret guns around Hollywood with new freedom in a sporty white Ford crown convertible. In only two months at the wheel she has collected four traffic-tickets and a smashed headlight. She also collects Eddie Fisher and Perry Como recordings and nurses a secret crush on Rock Hudson. Still a rabid TV and movie fan, she drags most of her dates to theatres and recently complained, “There’s not a show in town left to see!” She still doesn’t smoke or drink but right now she doesn’t need to. She’s always in a hurry, usually late and chronically vague and scatterbrained.

But all these things—even the tickets—are considered healthy signs by everyone who knows Maggie—including her mother, who knows her best. They just wish it had started earlier. Sometimes Margaret gives evidence that she does, too. When she posed for MODERN SCREEN in a bathing suit recently and viewed the results, her reaction was definitely not what it would have been only a few months ago. “Well, you won’t ask me to do this again,” gloomed Margaret. “I look just like you’d expect Margaret O’Brien would look!” But she’s wrong there, fortunately.

So far, the one important thing lacking to rev Margaret O’Brien’s life up to speed is an all-out, absorbing, real-life romance. Right now the most likely candidate is Bob Allen, the dark-haired, personable young Douglas Aircraft worker who late-dated her on graduation night and has repeated many times since. But twenty-one-year-old Bob has just picked up his Service greetings and chances are she won’t be seeing him much for the next two years.

“I’m not in love, anyway,” Margaret nails down the subject. “Marriage? Not for two or three years, anyway. Right now I’m having too good a time to think about that. I don’t want to rush things.”

But time and events are rushing things for Margaret. With such a late start, there’s still a lot of catching up ahead. The biggest threat to her half-hitch on maturity is still that she’ll pass over the very necessary business of living her life to the full as she chases her new adult ambitions. Even as she makes her comeback picture, Maggie’s praying each night to her patron saint for the chance to play Esther Costello in the story of that amazing deaf and dumb Irish girl, soon to be filmed in Ireland.

If she wins it she’ll play, as in Glory, a girl younger than her own years. But soon, to realize her ambitions, Maggie O’Brien will have to tackle much more mature roles. Ironically, she can never act her age convincingly on the screen until she acts it in her own life.

As one old Hollywood hand, watching her breeze through her Kentucky farm-girl part in Glory observed, “I never thought I’d see a kid star who could do it again. But this one can, and be as great as she was before. Only, she’ll have to be a woman first.”

That seems to be the all-important first port of call on the second Hollywood journey for Margaret O’Brien.

THE END

—BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1955

No Comments