Why Diane Varsi Says: “I’ll Never Go Back To Hollywood”

The winding main street of the small college town of Bennington, Vermont, sloped sharply downwards as it reached into the clustered shopping center of the town. At the top of the incline and walking towards the stores—which were shadowed from the warm spring sun by the steep rise—came a bobbed-haired young girl in blue jeans and her small freckle-faced son. As they climbed over the crest of the hill and started downwards towards the stores, the boy gave his mother a friendly tug by the hand, making her run down the slope, unable to stop.

“No, Sean, no,” she laughed, as her open sandals clip-clopped over the pavement and her light, empty straw shopping bag flapped back and forth in her other hand.

“But it’s fun, Mommy. I like it,” he said. “Don’t you?”

He turned his tiny face around to look up at hers.

“Yes, Sean. Yes I do—very much,” she said softly.

“Then why aren’t we together like this—all the time?”

“But darling we will be. I promise. Now you let go of my hand and I’ll meet you by the candy store,” she said, shaking off his grasp and laughing. And as she watched him run on, with his arms outstretched and making zooming noises like an airplane, she smiled a wonderfully natural smile . . . and looked quite radiant. “Hey—not so fast,” she called.

Two college students, passing by, turned to look at them. They recognized Diane. “She’s the girl who suddenly left Hollywood,” one remarked quietly to the other. Then two more girls, in Bermuda shorts and light sweaters, stopped to say “Hi” to Diane. They knew her too. She was already enrolled at Bennington College. She smiled back and caught hold of Sean’s hand as she reached the bottom of the hill.

Diane knew no real quick answer to her sudden walk-out from Hollywood, nothing she could tell the girls briefly in reply to the question she knew they wanted to ask. Because it had all started many months before. . . .

It was late afternoon and Diane was sitting at her dining-room table busily studying her lines. Over and over again she said words to herself, each time further submerging the person she was with the person she was supposed to be. She’d already read half a dozen books to help her further understand the girl she was portraying. She studied until she knew the character intimately. She knew the way her character would react to situations, the way she’d walk, stand, sit, lower her eyes, smile. She knew because in her deep study a change had taken place—she was this girl, Ruth Evans, twenty, a co-ed at the University of Chicago, and engaged to a young law student. And her story was “Compulsion.”

Suddenly she felt a tug at her leg. Unconsciously she put her hand out to fight it off, and again she felt a tug and heard a small, child-like voice say, “Mommy . . . Mommy go away.”

Diane stood up, shook herself and looked around her. She stooped over and lifted the little boy who had spoken into her arms and held him tightly. Then setting him down, she walked into another room and turned on the lights. It was dinner time. Where had the day gone? Almost trancelike, she went into the kitchen and started preparing dinner. She cooked the vegetables, got out the bread, the milk and the red jello that the little boy loved. Then suddenly the noise of the icebox door slamming shut brought her back into the world of reality.

She sat looking at the little boy—at her son—while he ate, laughing again and again at his funny white milk mustache. But inside, the words he’d said would not stop running around in her mind. It wasn’t the first time he’d tugged at her leg, or climbed up into her lap and said simply, “Mommy . . . Mommy go away?”

And as she thought, she began to realize what his words meant. He didn’t mean that she was about to leave the house. What he meant was that for the past few hours she had become some other person. He had watched her lose herself so completely in her role that he saw not his Mommy but a stranger, someone he did not know, a person called Ruth that he had neither heard of nor could understand.

After “Compulsion” she decided to take a rest and she was placed on suspension by her studio until she did a pilot for a new 20th TV series called “Whodunit.”

And then it happened. The last night of the “Whodunit” filming, she and the cast had worked overtime. It was one in the morning. She was tired and soaking wet, having been in a studio water tank for nearly three hours. This was a big scene, the scene where she is murdered by having her head pushed under the water and held there until she drowns. They’d done the scene again and again and always there was something wrong. Then she’d been told, “Try it one more time.”

She started to protest. It was almost two now, and she was no longer able to sustain herself. She said she did not want to do the scene again. Inside she had a premonition that she mustn’t do the scene again. But there were dozens of other people there dependent on her part. She couldn’t leave. Once more the actor who had to push her head underwater did his job. She felt herself going below water and as she went down her head struck something hard. She gasped for breath and rose to the surface. . . . Her head had evidently struck one of the wooden pilings of an ocean pier. When she reached the water’s surface she began struggling, but the actor, thinking Diane was still playing her part, and knowing her usual authentic intensity, put his hand on her head again as he was supposed to in the scene, and pushed her underwater. Again she hit her head and again she gasped for breath and struggled to the surface. This time when she came up she covered her face with her hands. The cameras continued to roll. What a dynamic performance, everyone thought. Again the actor’s hand reached out for her—but this time she turned and swam away. The director called “Cut.” She got out of the water and without a word she turned to walk off set. And as she did so she took her hands away from her face. They all stood stunned as they saw blood gushing from a gash in her forehead and the bridge of her nose. Only then did anyone realize Diane had not been acting—she had been really hurt.

Yet she was more than physically hurt. That day Diane made her decision. She had to leave Hollywood, to get away from acting which had always been so emotionally painful and harmful to her.

On Saturday, the 21st of March, on a side street in Santa Monica, California, a few miles from Hollywood, a white frame house stood quiet, empty, waiting for its family to return. On the front lawn, a profusion of purple and magenta flowers grew wild. The mailbox was overstuffed with letters. Inside the house, the large living room was still full of furniture. A guitar was propped up on one of the chairs, waiting to be strummed. And on the polished wood floor, a red and white stuffed dog was stretched out forlornly, as if waiting for someone to play with it.

From all indications, it seemed as if the family of the house had just gone away for the weekend. Yet, two days before, early on a Thursday morning, Diane Varsi and her son, Sean, had walked down the front steps of that house and had headed for the airport—not just for a weekend, but presumably forever.

The decision to leave Hollywood had not been a sudden one. It had been well thought out, well planned. Yet she’d told no one. Twentieth Century-Fox, Diane’s studio, was caught completely unaware when she walked into the office of executive Lew Schreiber, just two days before she left town, and calmly informed him that she was going. The next morning all Hollywood read the news over its coffee cups. A trade paper announced that Diane had “stormed into the front office and told ’em she’s giving it all up and going back to Vermont to write a book.” The basic fact was true; but she hadn’t stormed in, nor did she plan to write a book. She’d walked in quietly and said she was just leaving. And she’d done it while on the threshold of a brilliant career—she’d just finished “Whodunit,” got rave reviews for her TV debut in “Playhouse 90,” had the picture “Compulsion” still to be released, was talked about for key roles in “The Best of Everything” And her studio were even considering a sequel to her first triumph, to be called “Return to Peyton Place.”

To the press she explained, “It has nothing to do with the studio itself. I just don’t want to act anymore or be a part of this business. I don’t like some of the ways of Hollywood, but my reasons go deeper. It is the performing itself that I object to. I find it destructive to me. I don’t see any reason to be miserable just because other people say I should go on with my career If I have any talent, I will try to find some other outlet for it that will make me less unhappy.”

The news spread rapidly. While Diane prepared to leave, the town was buzzing.

The brief statement she’d made was complete as far as it went. It was all she could say. She could not speak of the inner torment, the unhappiness, the loneliness. Were there words to explain?

During recent interviews she was always polite but seemed a little unhappy when writers delved into her past. “Why do you always have to ask about my past?” she questioned. “Why not talk about today or tomorrow?” For the past was painful for her to talk about, yet she did so because this was part of the job of being an actress. And so she spoke of her early days in San Mateo, of her mother’s illness, of the time her father left them, and how she was shunted back and forth between schools, convents, desperately seeking love, affection, desperately wanting to belong to a group as well as to a family. And so they learned of her days and nights of torment and tears. She told and retold how it seemed as if nothing she could do was right, as if no one loved her, or understood her or cared. Only her’ grandfather, Joseph Varsi, seemed to believe in her, to encourge her.

It was hard to delve into the past and speak of the early marriage that became a disaster, hard to speak of the discovery of her pregnancy just as the marriage broke up. Yet Diane knew why the writers kept asking her about it because all of it had led up to the fascinating Cinderella story of her discovery and her one picture jump to fame and stardom in an Academy Award nomination.

Over and over she told about the day she and a friend left her home in San Mateo and hitchhiked to Hollywood. . . . How without fear they had stood out on a highway thumbing their way to a new life. . . . How they had decided to go on to Mexico but had somehow stayed in Hollywood. Settled in a small apartment, she told how her grandfather had sent money when she wrote to him to say that she had decided to stay in Hollywood and study acting. He had sent her monthly checks, encouraged her, was proud she She retold the story of her acting coach, Jeff Corey, bumping into director mark Robson, who was casting the role of Allison in “Peyton Place,” and how Jeff had recommended her and how she’d gotten the part that every young actress in Hollywood wanted and how in a matter of months she was transported from Diane Varsi, young vagabond, former folk singer, hitchhiker from San Mateo, into Diane Varsi, movie star. She told how the cast thought her aloof but how inwardly she was really just shy, overawed with the tremendous import of what had happened to her and most of all just plain scared. Each morning she would walk on set and say, “Am I still in the picture?” Or, “Haven’t I been fired yet?” And while the rest of the cast and crew spent their off hours relaxing, she’d stay in her room reading and re-reading the book and the screen play and analyzing and re-analyzing the character of Allison until she was Allison.

And there were always questions about her son, and her second husband, James Dickson. whom she sued for divorce in August of last year. Jim, who is still her business manager, took her to the airport when she left Hollywood that day in March. Then there was always the question, “Do you like acting?” And always the same answer, “No. It is not satisfying. I am miserable.”

And all the while she read constantly—to discover things about herself, about life. She studied the works of the philosophers, the dogmas of different religions, the teaching of Yoga.

No story ever written told fully of her wonderful warm sense of humor, her ability to laugh at herself as well as at the humorous things she saw around her. No one spoke fully of her fantastic devotion to her son nor her futile attempts to overcome the personal quirk in her makeup that would not allow her to shake off a role while she was filming.

During her third picture, “10 North Frederick,” Diane suffered what the papers called a nervous breakdown. She went to a hospital and for a week she was quiet and still and then the following Monday she was back on the set. The public read of the breakdown but did not read about the subsequent crying. They did not read how she fainted during a dance sequence for “Dingaling Girl,” the TV play, nor could they know that the calm, offbeat exterior was just a cover for an inside that was screaming with agony until it could scream no more until the agony turned into a quiet resolution to leave, to forget, to seek solitude. They did not know that after her week in the hospital she had sought professional guidance and had gone to an analyst for help. And he had agreed with Diane that at least for the time being acting was not the right thing for her. And when finally she made her decision to go to Vermont, she went quietly to tell him of her plans before breaking the news publicly.

After the awful struggle she had playing the role on “Playhouse 90,” she told another friend: “I can’t stand it. I thought I could keep control of myself I’ve tried . . . my God I’ve tried. But I just can’t go on like this. I’m leaving I’m getting out before it’s too late.” The friend thought she was just upset, over-wrought, he did not take her seriously. But the first week in March, Diane Varsi called the real estate agent and told him she would be leaving and that he was free to rent the house. The second week in March, she packed all her books and records and made arrangements with friends to stay with them in Bennington, Vermont—only at the last minute deciding to take an apartment there instead.

The idea of New England intrigued her. She’d grown to love the serenity of Maine during the filming of “Peyton Place.” By the third week of March she’d made all the arrangements, paid all outstanding bills, taken Sean to the doctor for a check-up, and then she called her theatrical agent and told him.

She called a few close friends, her stand-in Joan Dyer, and her long-time friend Carol Eastman, also an actress. Her ex-husband, Jim Dickson, already knew.

She explained she was leaving. She managed to arrange her time so that she could spend an evening or at least a few hours with each of those closest to her.

By Tuesday of the third week in March, her records, record-player, books, linens and dishes were on their way via railway express to Vermont. The other things she left behind to be sent on later. That same Tuesday evening, she knocked on a neighbor’s door. Could she borrow a few blankets, hers were all packed? And she said goodbye and walked back into her white frame house.

When she got inside she looked at a clipping, dated March 18th, that someone had sent her about her decision. It said she was going to write. She smiled to herself. For years she had sought release in writing, in jotting down bits of poetry, short stories, in rhyming words, words which helped express how she felt and yet in this too, as in acting, she was undisciplined. Maybe someday, Diane thought, I will be equipped to write, but not now.

A reporter called. Somehow he’d reached her private number. “Is it true, Miss Varsi,” he said, “that you are leaving Hollywood to get married? That you have a secret admirer with whom you are very much in love? A man you will be joining when you leave here?” Diane was noncommittal, polite, but she said nothing except, “I have nothing to say.”

And yet, as Diane hung up, she had an odd feeling. Was it possible that one of the reasons for her decision to leave was her devotion to a young actor now back East touring in a play? Was it possible that in him she would find part of what she was searching for? Was she ready again for permanent love? Were the scars of two unsuccessful marriages too deep to make her risk a third plunge, at least for now? Would people find out about her newest romance? Could she see him on her way to Vermont without the glare of publicity shining down on them? She didn’t know. She’d have to chance it. But one thing was sure. After seeing her family in San Francisco, she was planning to make a brief stop before landing in New York and then going on to Vermont. Was the person in Chicago a key to what lay ahead?

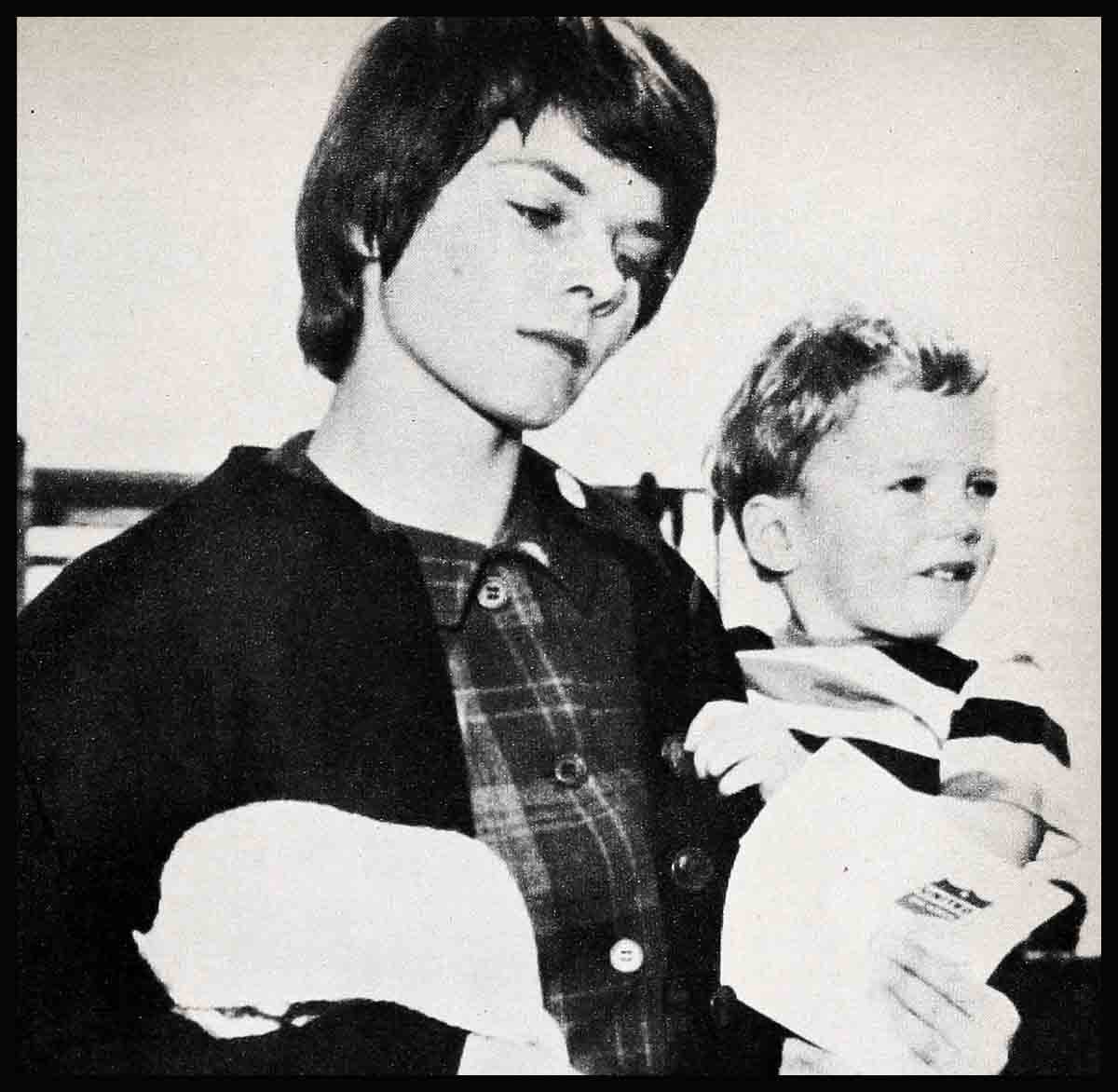

On Thursday morning, March 19th, Diane Varsi and her son Sean left Los Angeles International Airport. At the terminal with them were Diane’s friend, Carol Eastman, and her ex-husband James Dickson. Also there were a battery of photographers and reporters. As she walked up the steps leading to the plane, she clutched Sean tightly. When she got to the top step, she did not hesitate, did not falter, did not turn to wave goodbye or to take a last look at the city which had been her home for the past two and a half years. There was no use looking back, because there was no turning back. The die was cast and the decision made.

THE END

—BY MARCIA BORIE

DIANE’S IN TWENTIETH’S “COMPULSION.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1959