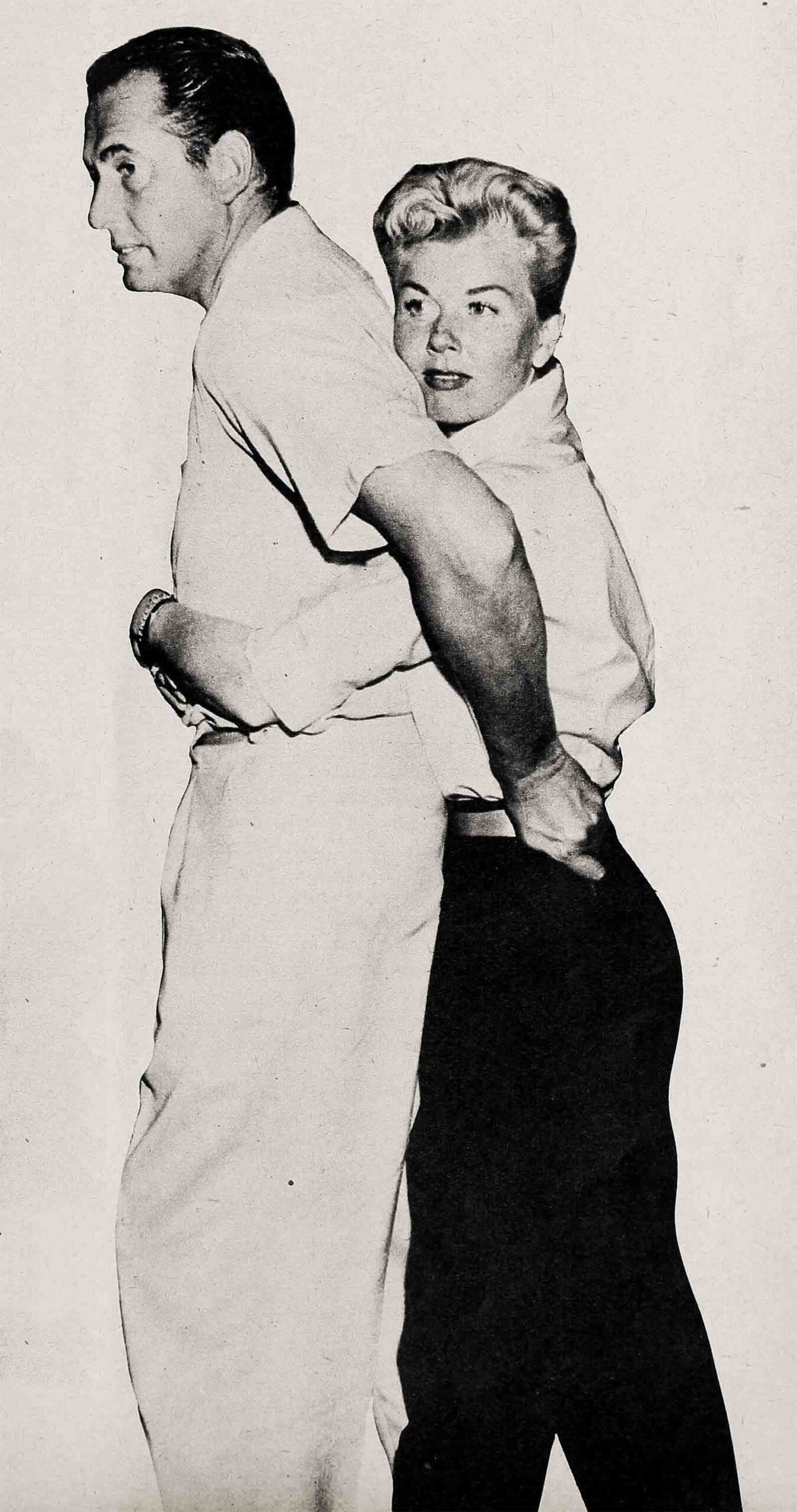

Hold My Hand—Doris Day & Martin Melcher

While lunching with Mr. and Mrs. Martin Melcher, someone asked Doris about an interview she had once given. The subject was glamour and it had made pretty funny copy, Doris being of the opinion that they could put a wig on her, arch her eyebrows up to here, plaster the famous freckles with make-up—and still come up with nothing.

Less well publicized, the three-million-dollar corporation known as Doris Day also has eyes like star sapphires that focus intently on the face of a speaker. Now, listening to her own old words, she wasn’t in the least inclined to deny them, but her expression indicated that she was a noodlehead for having uttered them in the first place.

“That must have been a long time ago,” she commented with a typically quick, vigorous nod, “because I’ve stopped knocking myself. Nowadays, if fans stop me for my autograph and tell me how beautiful or glamorous I am, I think it’s great. Even if I don’t happen to agree with them, I’m glad they think so.”

“I think you’re glamorous,” Marty said with gallant promptness.

Doris gave him what might be described as a wifely look, composed about equally of love, appreciation and are-you-kidding? “Modesty certainly is a virtue,” she resumed, “but the trouble with knocking yourself is that after a while you start believing it. You think you’re an ugly duckling, you begin to act like one and then other people are convinced. Not any more! Anyone who wants to think I’m a dazzling, glamorous movie star—why, great!”

“Anyone but her,” Marty interpolated with a wry grin. “Know what she said to me the other night? She was sitting at her dressing table, brushing her hair, staring at herself in the mirror. Frowning, sort of. Suddenly she turned to me and said, ‘Do you think my face is right for pictures?’ ” Marty shook his handsome head. “She’s only been making hits for eight years, and she wants to know if her face is right for pictures!

“I’ll tell you something,” he continued. “She still doesn’t know she’s a movie star. Doris’ greatest quality, besides her talent, is her complete naturalness. If she hears a car in the driveway, she’s so anxious to know who’s visiting us that she’s hanging out the upstairs window, yelling, ‘Who is it?’ I have to haul her back and say, ‘Honey, wait, wait! I’ll go down and open the door.’ I’d say that my wife isn’t so much a movie star as a very talented girl whom circumstances have pushed into the limelight. She still doesn’t take to the idea.”

Doris Day has to be one of the best investments the studio ever made, because she never has made a picture that wasn’t a hit.

“If I have made progress,” Doris says thoughtfully, “it’s because I had to. I often wonder if I would really have worked this hard without the incentive of Terry’s future. Someone once told me that Aries people are inherently lazy—fortunately, I haven’t had time to find out from personal experience whether it’s true.”

She was attacking a steak with evident relish—but then, as Marty says, Doris can always eat. “I remember the day we got married. We went to Van Nuys and found out that they issued licenses for everything except marriage, so we had to go to Burbank. About this time Doris got hungry, so first I had to take her home to eat!”

“He said, ‘Imagine anybody being hungry at a time like this!’ ” Doris chortled. “Then on the way to Burbank I decided to pick up some fabric for a chair cover, and we got into an argument about the color.”

“A discussion,” Marty corrected. “It was much too early in our relationship to start arguing.”

Do not be misled by their casual words into thinking this was not a hearts and flowers romance; it was. Doris has got herself quite a guy, and she knows it. He’s handsome and always impeccably dressed, he’s one of the smartest business men in Hollywood—and if Doris consistently reflects a happy personality, Marty sets the mood with his eternal but gentle teasing. Since their marriage she wears a new air of assurance, knowing that Marty is there in the background, making the big decisions, quietly seeing that the necessary gets done and the trivial doesn’t harass her, looking after her interests.

As Doris has expressed it, “I can’t give Marty credit for starting me on my movie career, but I certainly do give him credit for managing it wisely and thoughtfully—and for being the right guy for me.”

And she’s the right girl. Their references to their marriage are a polite and subtle cue that you are off-limits in attempting to invade that area of their life. They aren’t going to tell you any more than that about the way it was, because they share a conviction that how much they love each other and why is their own business. If sticky-minded reporters asked Doris whether her husband remembers to kiss her every time he joins her for lunch in the commissary (he does) she wouldn’t answer. Similarly, while Marty is never an unreasonable man, he is very protective of Doris; if a subject is either sacred or, for some reason, painful to her, we just don’t talk about that. And those who have insisted on stories on those subjects have discovered to their chagrin that Martin Melcher’s memory is enviable.

Mr. Melcher is always welcomed by the press. Partly because he’s an intelligent and witty man, but also because he relaxes Doris, who has a deep and unshakable antipathy to doing publicity. She does not—repeat, does not—consider herself too big to bother. She tends to be a little wary because—what’s to write about a perfectly normal, ordinary girl named Doris Day who doesn’t happen to like rigged-up publicity? She has a Cadillac and a pool and a volley-ball court in which she takes deep pleasure and which she is glad she can afford. She isn’t about to be photographed in the kitchen pretending that she does her own cooking. Why should she, when she hates to cook? She loves her family, camellias, new clothes, food, singing, and playing with Terry—not necessarily in that order. She has an aversion to the modern contraption called a telephone. In her studio dressingroom there is a drawerful of chewing gum of every size, shape and flavor, and she’s as tickled as a kid when she gets someone else addicted to her favorite vice of chewing away on the set. She has a list of hit records as long as your arm. She’s going over to Metro to make a picture, her first time off her home lot. So, what’s new? Who’d be interested in reading stuff like that? Nobody, in the opinion of D. Day—so what fantastic thing are they going to print about her instead? It’s enough to make a girl wary.

But tall, urbane Marty is also there. He may start the ball rolling by telling a joke, which will be new and very funny. This reminds Doris of her currently favorite story and, completely unself-conscious, she launches into its recitation. Marty listens, chin in palm, and at its conclusion he ribs his wife with deadpan glumness: “You know, honey, this is the third time I’ve heard that story, and I still don’t get it.” A bright-eyed blue glance flashes at him; they’re playing the typically married game, and Doris is amused. And this is how you get to know her, through the fine Italian hand of Marty Melcher.

Now that the mood is set and the key is minor, Doris comes alive. If you mention a favorite record she made last year, she’s likely to sing the first few bars of it, to the surprise of no one present. She confides the matchmaking plans she has for one of her friends, eyes sparkling. At this point Gordon MacRae enters, kisses her warmly on the cheek, straddles a chair, and drones, “I was born on May—”

“Who cares about the dull details of your life?” Doris joshes—and then asks to be brought up to date on them. “How’re Sheila and the kids? What’s doing with Oklahoma? You know, your hair’s longer than mine now. Do you like it over on the Metro lot? I’m glad, because I’m going over there to do my next picture.” She sends love to Sheila as Gordon departs, observes affectionately, “There’s a really talented boy.”

Herself? Lucky, she has called it. “The only acting I ever did before I came to Hollywood was in a Mother Goose play. I was a duck. There was a goose in it, too, the star—but I wasn’t even smart enough to play the goose!”

On her approach to her profession: “I have great admiration and respect for talent, enterprise and honesty; I have no patience with sloppy living or sloppy working. I think that fame most often comes to the people who deserve it, but for myself, I don’t think I could have done it for the sake of seeing my name in lights alone. The incentive for me had to be more real, more immediate—my family. Not that I discount my picture work and the things that being an actress made possible, but I try never to over-emphasize that kind of success. I prefer to temper my enthusiasm for professional success with gratitude for the success of my marriage and home life.”

Right now the immense enthusiasm Doris gives to everything she touches is centered around the recently-formed company of Martin Melcher Productions, Inc.; this is going to be the greatest, the most. Apprised of her big dreams, Marty said with a grin, “My wife’s business sense is keen, but she isn’t half as relentless as she sounds. What she does about the company is to dart in and out of our conferences—and she’s a darting expert. She always shows up at exactly the right time.”

If Doris does have a good sense of business, it’s just an extra doodad that she doesn’t need with Marty around, and perhaps it gets a little rusty. There was the time, for instance, when her total contracts soared to a cool $3,000,000 and Marty thought it expedient to make Miss Day into a corporation. This involved lawyers to be consulted, papers to be drawn, endless other legal mishmash to which he attended. Then he carefully explained to Doris the reason for and procedure of every step taken. She signed her name where indicated and asked indignantly, “Do you know what they want for those draperies I was pricing?” Business sense, yet!

It could be that in these times a cheerful, happy personality is suspect, but Doris Day gives the lie to those who would say that hers isn’t for real. She has learned a profound lesson: that for her love is more essential to life than bread, that happiness is gained in precisely the measure it is given. Why else does she, between scenes, meet more visitors to the set than any other star in Hollywood? Why, when she could be resting in her dressingroom, does she stand patiently, smile radiantly, having her picture taken with the man from Kansas City whom she will never see again?

To Doris, it figures; she is happy, it only costs a little extra effort to make other people happy—and she pays for what she gets. Everybody does, one way or another.

Such a sunny, lovable girl. But nobody, not even Marty Melcher, is going to persuade this one that she GLITTERS in upper case letters, that the sound of her sigh or her smallest thought are of importance. She’d be an idiot not to be able to tell that she has arrived by the material things around her. But in her own pleasures, in her own mind Doris is still a simple and uncomplicated human being.

“You know what?” she says with the kind of candor that undoes her severest critic. “We were at this party and Marty pointed out Artur Rubinstein to me. In a little while be came right over and told me he felt that he had already known me a long time. I said, “You do?’ and he said yes, because his daughter collected my records. Can you imagine a great pianist like Artur Rubinstein bothering to say a sweet thing like that to me?”

END

—BY ELLEN JOHNSON

(Doris Day will be seen next in Warners’ Young At Heart.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955