It’s Murder Man!—Van Johnson

Charlie Morrison is one of Hollywood’s most beloved institutions and so is Charlie’s club, the Mocambo. So when Charlie had a stroke and landed flat on his back in the hospital, half the stars in Hollywood took over for him, providing the entertainment and personal touches that Charlie had always given his place. The other half came to watch. And there was plenty to see. For ten days Charlie’s friends knocked themselves out, putting on performances such as not even Las Vegas ever saw. And then they sent tape recordings to Charlie, just to let him know that someone was looking after the club.

Van Johnson found himself scheduled to do the fourth night’s show, all by himself. Being an old friend of Charlie’s he accepted the offer for the honor it was, and said yes promptly. Then, very quietly, he had a fit. There wasn’t enough money in the whole of Hollywood to have lured him back onto a stage. There wasn’t anything but friendship that could possibly have bought him for what he knew would be a repetition of the most terrifying moments of his life.

Which moment? Well, there had been the times when his life appeared to be in danger every time he set foot on the street. There were the days when, if he had his coat buttons sewed on too tight, the fans would tear off half a lapel and maybe a sleeve with them. There were the nights when they climbed through the windows into his house and wrote messages to him in lipstick on his walls, his tables, even on his car and the hotel to which he fled for refuge. It was great for the lipstick manufacturers, but for Johnson, it was altogether murder.

But he wasn’t expecting that now. Those days were pretty well over, which was more than all right with him; for years he’d been trying to finish them off. But he was subject to different attacks these days, and no group of howling girls could make a dent in his aplomb like those butterflies in his stomach.

In the first place, he had completely forgotten the last act he had done before a live audience. It had been at The Sands in Las Vegas, and when it was over, Van had blotted it out of his mind. He’d been a hit, all right. But the praise and the applause and the not inconsiderable money and his wife Evie’s pride in his success couldn’t make up for the terror that gripped him before every performance. He was actually physically ill when he thought of going on. But everyone raved and for a while there, he almost thought he had it licked. But when that two weeks were over and the Chicago stint over, he realized what a terrific strain doing the act had been. Better the bobby-soxers. You wouldn’t catch him letting himself in for butterflies again.

But now he had to. So he called the writers who had done his last show, and started over. Evie found some of his scores in the basement. The show began to shape up. And all the while he kept thinking that this would be even tougher than the other, that there would be Hollywood people there this time, his friends, his neighbors, fellow-actors. It had been terrible to think of flopping in front of strangers, but what if he fell down here?

He sought out Frank Sinatra, hoping to get some words of advice from the veteran of personal appearances. “What about make-up?” he worried.

“No make-up,” said Frankie. Well, that was something learned.

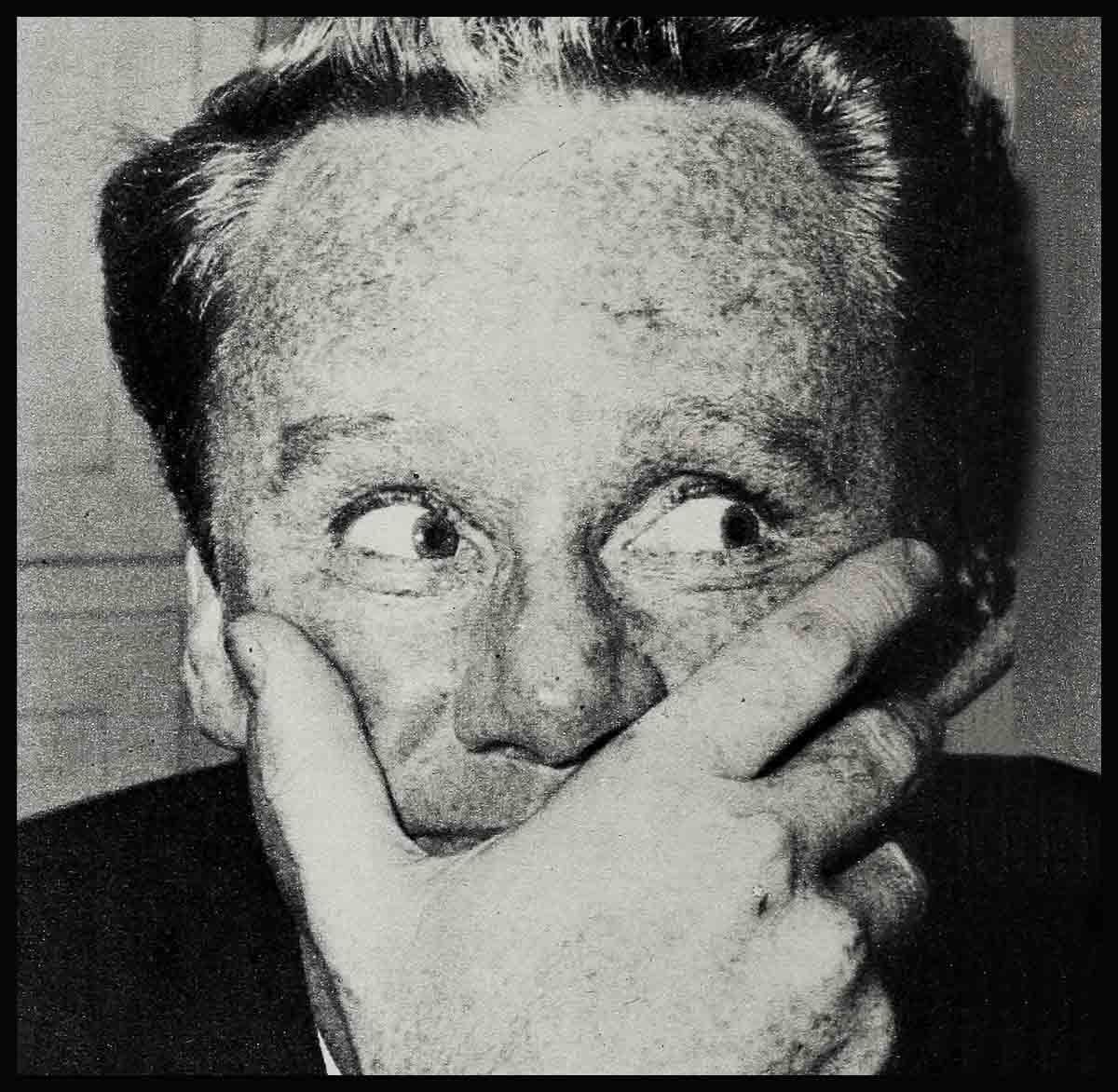

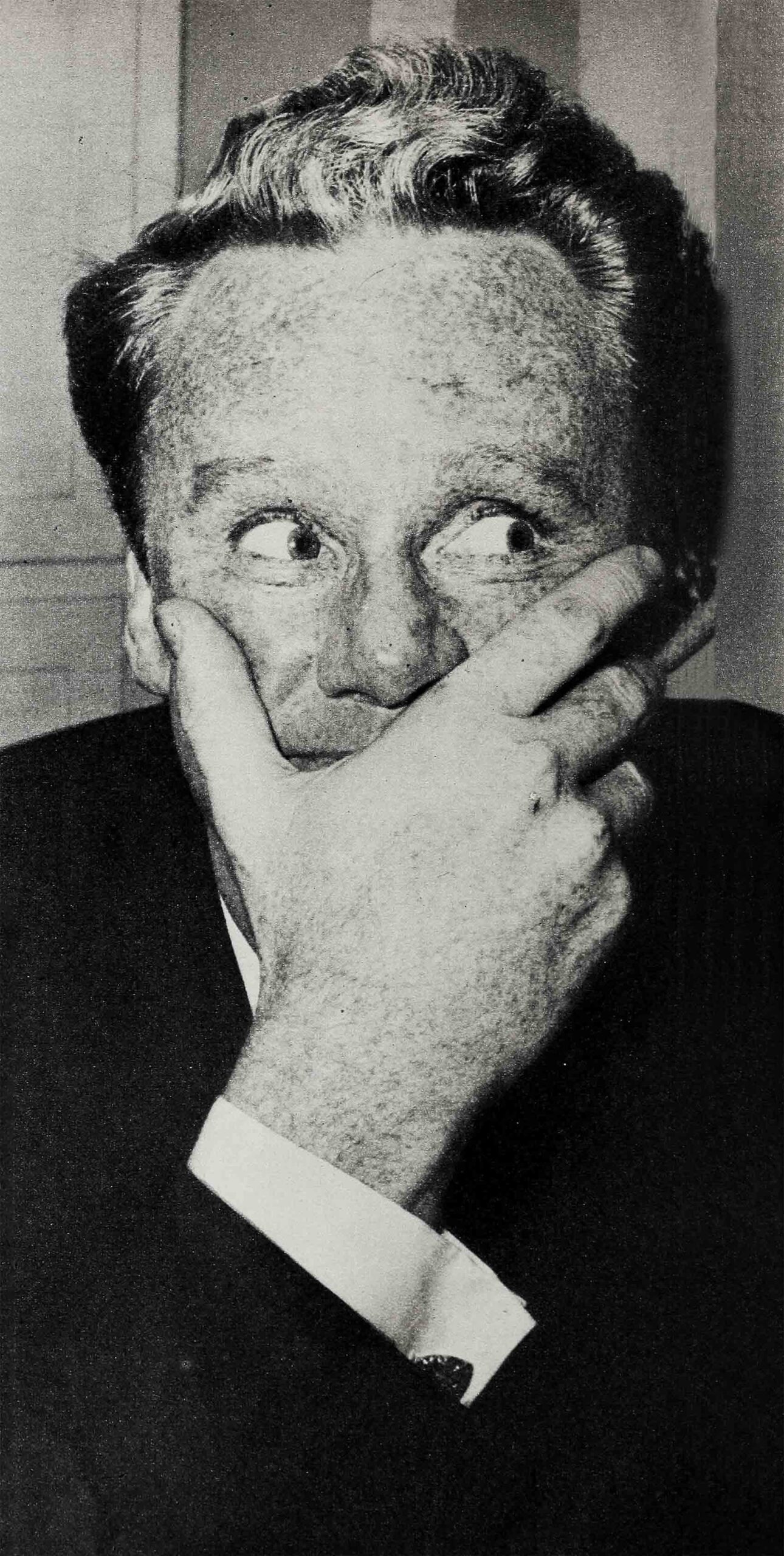

On the day of the show Van couldn’t eat. He couldn’t pace the floor. He couldn’t stay in bed. He went out into the yard to get some sun on his face. He had become so pale the freckles were standing out on his face like ink-spots. He spent an hour lying on his back facing the sun, but when he looked at his watch he had been there only ten minutes. By evening he was in such a state of nerves that when he went up to take a cold shower, the first drop of water that hit him nearly bowled him over. On the way to the show he looked like a man going to the electric chair.

Mind you, going on stage had not always been such a nightmare. There had been a time when an opening night was the moment Johnson lived for, hoped for—and frequently went hungry for.

He was born on Ayrault Street, Newport, on August 25, 1916, and he still had a Swedish accent in his songs when he was ten years old. There were lots of songs. He sang while he mowed lawns, while he learned the rudiments of plumbing from his father, Charles Johnson, and he sang while he swept out the beach cabanas at the gold-plated resorts of Newport. Quite inevitably he was told he should go on the Stage, and just as inevitably he was “discovered” at frequent intervals. Being a serious youth, for all his vocal exuberance, he took his advisors seriously, and since this is a success story, it naturally led to a period in which when he had worked up to starvation wages he was at peak.

It was then that he discovered that while it was fine to have others discover you, it might be more practical if one discovered oneself. So Van discovered Van. With that he was off.

Said the dynamic Billy Rose, looking over one of his multitudinous casts at the Texas Centennial in Dallas, “Give me ten more like that redhead in the chorus, and we can let the other thousand go.”

Work. Not just ordinary work, but what is known in his trade as beating your brains out. He worked with a group called Eight Men of Manhattan and a gal named Mary Martin, and Mary Martin said, “Come on, kid, you’re going great.”

He sang as the eighth man of Manhattan, when he sang, until his six feet, two inches of brawn was reduced to six feet, two inches of bone, and even the bones were getting on the emaciated side. By 1937, when he had reached the mature age of twenty-one, he had the relatively secure berth of a chorus boy in New Faces of 1937, and it was so good that it has continued to be up-dated. The latest new face of major excitement has been Eartha Kitt.

So he was discovered all over again, and of course this led to a big part in the chorus of a Broadway play—a real good one, incidentally—called Pal Joey. Opening night held no particular terror for him then. He even had a few lines to speak, and when he sang, it wasn’t that he crowded the chorus, but the rest of them might as well have gone home. Being a hep town, Hollywood called him and assigned him to a role in a thing called Murder In The Bighouse.

Today Van could do what his part required, but at the time it was like asking a Boy Scout to take over for Al Capone. Months after the picture was completed and Van was back on his accustomed diet of frankfurters, one for breakfast, one for lunch and one for dinner, another hard worker called Lucille Ball, whom he had danced past along the way, said, “Hey, I know where you can be useful.”

That was the one that did it. Lucille’s suggestion led to a part in The War Against Mrs. Hadley. Van knocked it off in fine style, and he was in. In for what?

Just fame, fortune, success and a hole in the head. The hole in the head is the only accident in the story. One day early in March, 1943, being the movie fan he is and always will be, he was on his way to a Katherine Hepburn movie. In the car with him were his best friends, Keenan and Evie Wynn, not to be lightly dismissed from his story. The other car appeared out of nowhere, and the resulting crack-up has been considerably garbled. Here from Van himself, is what happened:

“Honest, it was the war that saved me. Show business had taught me to save for a rainy day, so for months I had been donating blood to the Red Cross, figuring that with my low draft number, I’d be needing it back any day now. All told, I guess I had parted with about two gallons, and my body was getting well-adjusted to the drain by the time of the accident. When my coupe turned over, Evie and Keenan went out the side, but I went over the windshield, taking along the rear-view mirror with my forehead as I went. It wasn’t a happy deal, and it took all the blood I had donated to get me back into the world again, and even then I might not have made it if my body hadn’t been prepared to deal with a loss of blood. Talk about casting your bread upon the waters!”

Van spent three months in the hospital, bone and skin from his arm being used to patch the shattered bone and skin of his forehead. As far as his draft board was concerned his head injury and weakened arm put him out of the war. But he did a lot of thinking, and anybody who saw him as G.I. Joe and again in his unforgettable Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo knows that if he couldn’t go to war himself, he did a masterful job of bringing it home to the rest who couldn’t go.

By that time the cries of the bobbysoxers were loud in the land, and they wanted Van. They demanded him with shrill screams, with 50,000 letters a month.

Not even Frankie Sinatra got the personal hounding that was Van’s lot—and still is to no small extent. Frankie was a voice on the air and on records, and until he made a personal appearance in a town, he could walk a few blocks in reasonable security. Van, in the smallest town with a movie theatre, was better known than the boy next door, with the non-saving grace of being and appearing as much like himself onscreen as off.

As for the privacy of a home, it was routine for Van to be awakened at all hours, along with the neighbors for a block around, by bobby-soxers chanting, “We want Van,” usually to the accompaniment of handsful of gravel pinging on his windows. Small wonder he sought the sanctuary of a hotel and a secret room number.

Van, who had been a kid not long before, and had had his idols—though not so violently—understood and accepted it good-naturedly. What was harder to understand was that the bobby-soxers were allowed to grow up, but he wasn’t. Even back in 1947, by which time his original fans had grown up, met their real-life heroes, and were wheeling baby buggies, a scream of indignation went up at the notion that he would desert them to get married himself. He who had been raised by his grandmother from the age of four, and bached it with his father from the age of ten, and lived alone all his professional life, was not permitted the joys and comforts of matrimony which his fans were shouldering the instant the right mate came along. That was unreasonable.

His long-time friends, the Wynns, had come to a parting of the ways, and what had been friendship between Van and Evie now materialized into something much more substantial. In a ceremony in Juarez, Mexico, they became Mr. and Mrs. Van Johnson, and the long-time friendship—now between Keenan and the Johnsons—has continued uninterrupted to this day.

So on January 25, 1947, Van took on not only a wife, but a couple of charming sons. Almost a year later, on January 6, their daughter Schuyler Van Johnson was born. There was no revolution. The bobby-soxers quickly adjusted to the shock and moved right back in, augmented by their older sisters who could appreciate a movie star with three kids.

In fact, so vast was the adolescent and mature sweep to Van that psychologists were compelled to make scientific note of it. They found in his popularity a healthy trend. The “kid next door” had moved into the top spot as “the national lover.” Pointing out that heretofore female acceptance of screen lovers had tended toward the romantic, dashing types like Rudolph Valentino, Clark Gable, Robert Taylor, they saw in Van’s grin, freckles, and unkempt hair a turn toward “the realistic acceptance of men as they are.”

What more could a movie star ask? Not only was he accepted by his millions of fans, but he had the approval of science!

Well, for one thing, he could ask for something that might be, maybe, a little bit important? Being an entertainer, Van has a high regard for entertainment as such, but so do Spencer Tracy, Humphrey Bogart, Gary Cooper, Jimmy Cagney and the other dramatic actors. How about moving into that league? They provide entertainment, but they provide much more. It was that “much more” that Van wanted.

That was when he left the comfortable fold of MGM, where he had become something of an institution, and went out into the cold world of the free lance. Shortly thereafter Stanley Kramer, remembering Van’s vivid portrayal of Ted Lawson in Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, suggested that he play Maryk in The Caine Mutiny.

It was a tough part, filled with mental and physical violence, and it was to be played without the make-up that concealed the scars on his forehead. Opposite him would be the master tough guy, Humphrey Bogart, from whom no one ever steals a dramatic moment. So big was the challenge that as Van says, “It scared me to death,” but it was what he was after, and he knew that if he failed on that one, it would be back to the light entertainment for him for keeps. He passed the first of the tests of professional maturity he had set up for himself.

But the second test was the agonizing one. Las Vegas nightclubs were hiring the top talent in the land, each club vying with the other to hit a peak of lavish entertainment never seen before in show business. The entertainer who could perform there, and survive the intense competition, could perform anywhere. With the help of his musical friends, Van got together an act that was part song, part patter, part dancing and all Van Johnson. He wowed ’em. He took the act to Chicago, and he wowed ’em there. But the price was tremendous.

“The critics were kind, and the people were just wonderful, but every night was opening night for me. I couldn’t get used to it. Every night I’d sit in my dressing room in complete agony, drenched in cold sweat, and dreading the moment I had to go on. Other performers kept telling me that the ‘opening night jitters’ would go away, but instead they got worse. When I finished the Chicago run, I was so worn out that I knew I could never face an audience from the stage again.”

The memory of his pre-show torment haunted him until it became something of an obsession. He even turned down good stage roles because of his fear.

In pictures he was an entirely new man. He returned to MGM to star in the tender, sensitive The Last Time I Saw Paris, and then he went to London to make The End Of The Affair. Both required the utmost in acting ability, and the latter, with its deeply serious religious theme, will long be remembered. But the stage had somehow become impossible for him.

So actually, except on a superficial level, he hadn’t passed his second test. He hadn’t entirely become the new Van Johnson who was to replace the old. In a way he had given up. Well, so what?

So Charlie Morrison got sick. What do you do when fate hands you something like that, shoves you back against a wall you’ve given up beating your head against and says, “Try again; you’ve got a thick skull.” Obviously, you get out the Band Aids and bang away.

And so, on the big night, in a state of semi-shock. Van headed for Mocambo.

“I remember,” he said afterwards, “climbing the stairs to my dressing room, and that’s all.”

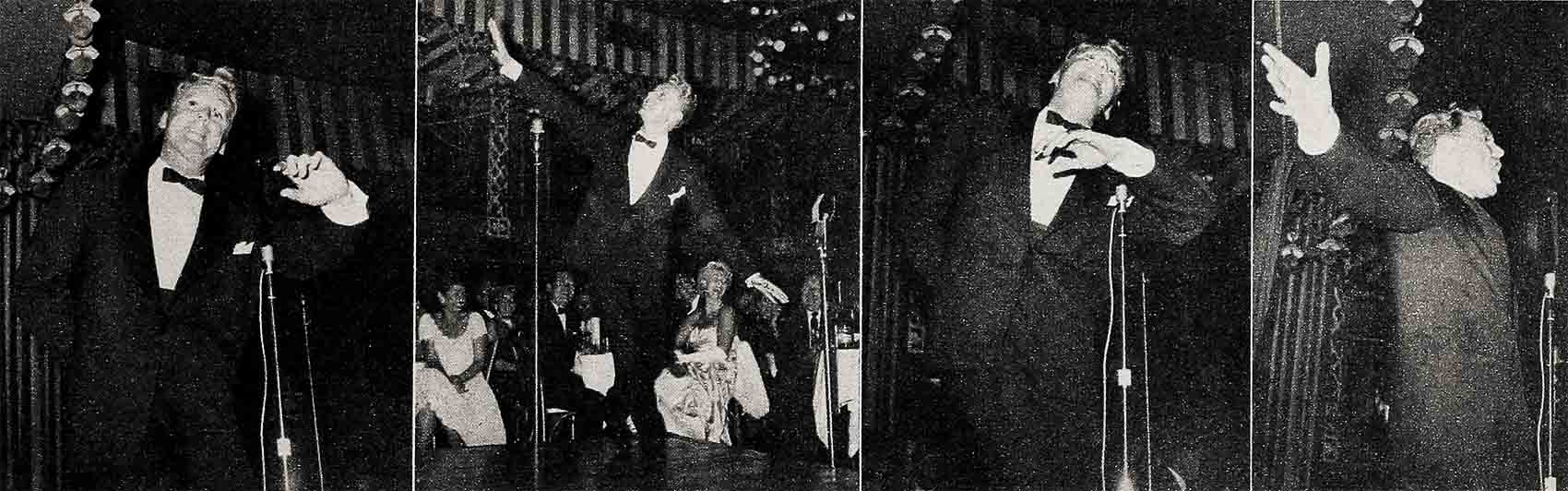

But that is not what the vast audience remembers. They saw this redhead come out and put on a forty-minute show the likes of which they had never seen before. When it was over they hollered, they whistled, they bellowed for more.

Van listened in dazed disbelief. He had no more. His act had included everything in his repertoire, and it had exhausted the last bit of starch in him. But still the frantic din continued. And it got to him, deep inside. His grin came back. His freckles lost their prominence as some of the color returned to his face. He got up, and there was a bounce in his step. He didn’t have anything more, but he could give them more of the same.

He did the part called “The Old Actor’s Dream,” and there was not a sound from the house as he sang the lines, “But nothing ever ends, as long as you have friends.” He sang it like he meant it. The audience knew that he meant it. Charlie Morrison, hearing the tape recording of the show, knew the meaning of it.

But something did end that night. Mentally, that was the evening Van Johnson really handed in his crown as King of the Bobby-soxers. Once his fan mail had reached 50,000 letters a month and his freckled face had decorated the covers of eleven national magazines. Once there had been so much attention, so much sound and fury, that one Van Johnson had been buried under it. This can happen. There are more painful ways of getting lost than under a few million dollars, but there are few things nicer than being found. At Mocambo Hollywood had discovered Van Johnson once more, and he liked it fine.

Another thing that ended was Van’s fear. This time he had really passed his second test. Not that he will be returning to the stage immediately. First he goes to New York to star in Miracle In The Rain for Warners. Then to the Salzburg Music Festival in Austria, where he will play in Rosalinda. That will occupy his summer.

And daily, scripts and offers come in. Parts for the new Van Johnson. Parts for the Johnson who sang at Mocambo,

“Here I am, back where I started,

Back where I belong.

I never thought at my old age,

I’d ever want to go back on the stage—

But here I am, back where I started—

Started with a song.”

And discovered, somewhat to his surprise, that he meant that, too!

THE END

—BY GEORGE SCULLIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1955