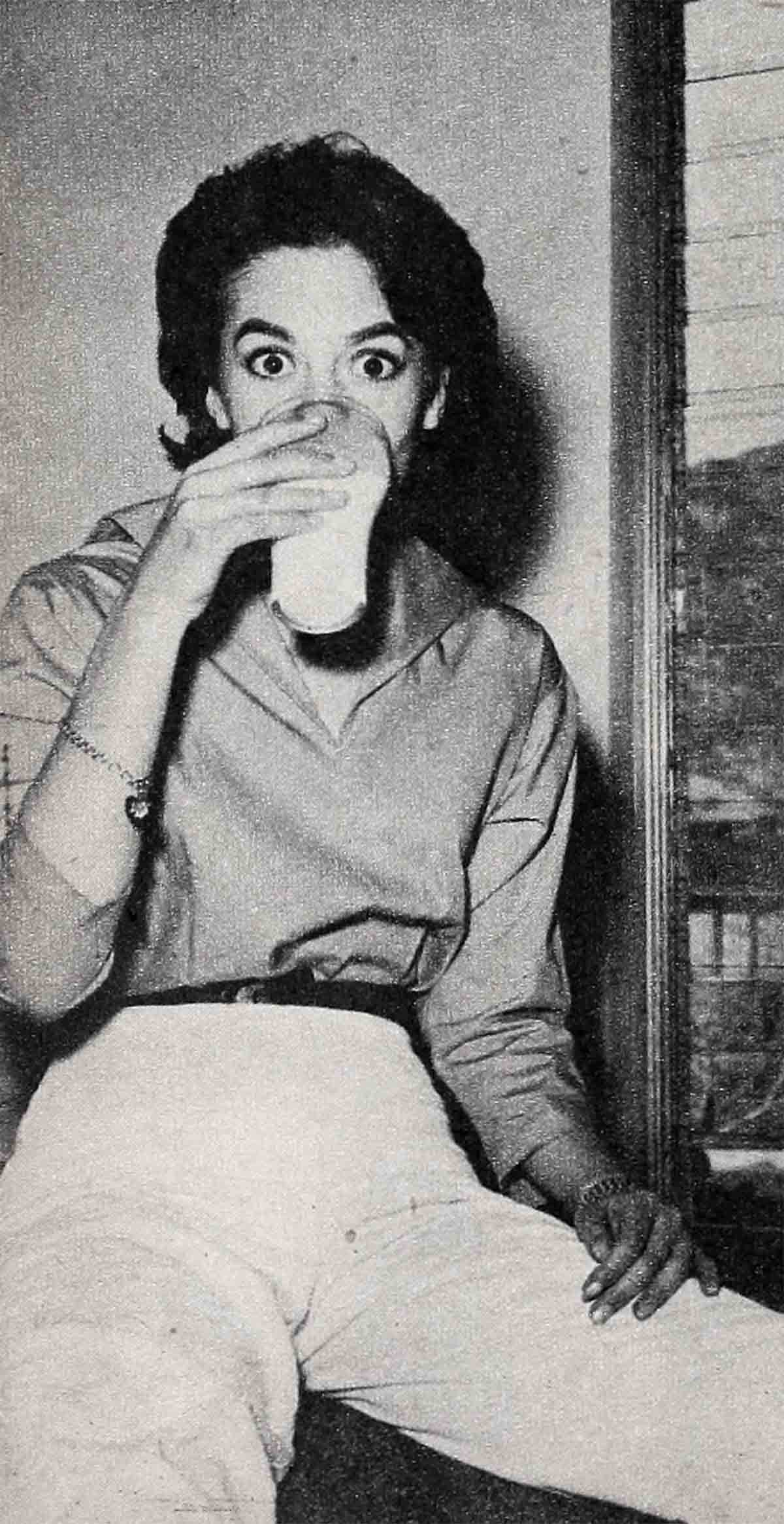

Don’t Sell Natalie Wood Short

The insistent ringing of the phone next to her bed. jarred Natalie Wood out of a deep sleep, though it was ten o’clock in the morning and the sun streamed through her windows. She sat up, drowsily brushed her dark hair from her face, and picked up the phone. An executive at her studio, Warner Brothers, was calling. He said, “Sorry to wake you, Natalie, but I thought you’d like to know you’re in.”

“You’re in” meant only one thing to Natalie. She had been chosen to play the title role in “Marjorie Morningstar,” the part she had been dreaming about for months.

She managed some polite words of thanks, hung up the phone, then bounded off the bed, threw up her arms and yelled, “Yowee!” Her mother, who had been cleaning downstairs, dropped her dustcloth and rushed to her daughter’s room. Natalie pounced on her with a bear hug. “I’ve made it, Mother, I’ve made it!” she shouted. “I’m Marjorie Morningstar!”

She waltzed her mother around the room, then collapsed on the bed, laughing happily.

Yes, Natalie Wood made it. With this picture, she’s no longer just a movie star. She’s a top-ranking, first class, bigtime star. And to make the triumph sweeter, she had come out on top in one of Hollywood’s most extensive talent quests. For over eighteen months, Warner Brothers had been searching diligently for a young actress to play the heroine of Herman Wouk’s best-seller. More than a score of actresses were tested, many of them top “name” stars. Production was held up twice.

But—what is this going to do to Natalie? The girl who, after working in movies for thirteen years, has reached the top at the tender age of nineteen?

Shirley Temple, Mickey Rooney, Deanna Durbin, Judy Garland, Elizabeth Taylor—all of them made the bigtime as youngsters, too. And all of them, despite their great success (or perhaps because of it), suffered much heartache. Their first marriages ended quickly in divorce. Their search for happiness has been long and tortuous—in the case of Judy Garland, nearly tragic. How can Natalie avoid the trouble, despair and torment that have so often wrecked the lives of Hollywood’s most talented young people?

The question is a lively one in Hollywood, for during the past year Natalie has not only accomplished the difficult transition from child actress to top star, she has become one of the most controversial personalities in the film colony. Her numerous boy friends, her hectic “romance” with Elvis Presley, her flamboyant behavior, her flashy cars, her minks, have brought down a deluge of criticism upon her pretty little head.

“Natalie Wood?” sniffed a well-known actress. “No, I don’t think she’ll be able to take stardom.”

But director Nick Ray said recently, “Don’t sell this girl short. There’s a lot more to her than you’ll see in the beginning.”

“To my surprise,” said Marsha Hunt, “she turned out to be utterly professional while we were working together.”

“Natalie acts girlish and goofy sometimes,” said a close friend, “but when she’s got something important to do—important to her—nothing stops her. Nothing. Her ambition is almost frightening.”

These three people who spoke in her favor know Natalie well. Nick Ray directed Natalie in “Rebel Without A Cause,” the picture that marked her emergence from pigtail parts. Marsha Hunt appeared with her in Warner’s recent “No Sleep Till Dawn.” The third girl, who prefers to remain nameless, has been one of her closest friends for three years.

All three are in agreement on one point: the question of whether or not Natalie can cope with stardom is all but academic—in the mind of Natalie Wood.

“When Natalie wants something, she gets it,” says Bob Wagner, one of her steady escorts.

The truth of that is borne out by Natalie’s campaign to get the part of Marjorie Morningstar. More than a year ago, when she heard that Warners’ had bought the book, she went out to a bookstore and got a copy for herself. By the time she read the description of the heroine— a small, fragile, dark-haired girl with luminous eyes—she knew she was physically perfect for the role. It was then that her campaign began to roll. She had to come to New York a couple of times in the summer of 1956 to make personal appearances for two of her pictures, “The Burning Hills” and “The Girl He Left Behind.”

During those visits, she sometimes would vanish off the face of the earth in the afternoons. The publicity people assigned to escort her were frantic. They couldn’t imagine where she was going. And when they asked her about it, she would say nothing.

Natalie actually spent the time wandering around the streets of New York’s Upper West Side, the scene of Marjorie’s young girlhood. She went into stores and supermarkets, minding her own business but listening carefully to the people’s speech and watching their mannerisms.

Back in Hollywood, she read the book again with new understanding. Then she began to practice Marjorie’s mannerisms in her conversation with friends. “Some of us,” said Wagner later, “got pretty sick of it. ‘Lay off the Marjorie bit, will you, Nat?’ we used to say.”

Natalie refused to stop. “I’m going to be Marjorie,” she said to friends, “wait and see.”

She achieved an astonishing transformation. The old gamin haircut gave way to longer curls. She acquired a New York accent. She rattled off sentences that were, in their own way, as perfectly imitative of Upper West-Sidese as Carroll Baker’s Southern accent was perfect in “Baby Doll.”

Thus it came as no surprise to anyone when Natalie finally was picked for the part. It was no surprise to Natalie, either. “There isn’t any doubt in Natalie’s mind but that this part will be the one that will make her one of the greatest stars of all time,” says a young man who has taken her out frequently. “The only thing that’s ever bothered her about stardom is—when?”

Certainly few people in Hollywood ever have appeared so bound, driven, dead-set and determined upon making a mark. “Natalie would do anything for publicity,” one of her critics has remarked.

So it would appear, at first glance. Last October, a columnist commented on her as follows:

“HOLLYWOOD IS TALKING ABOUT: The way Natalie Wood gets into every act where she can be sure of some publicity, even posing with a California college boy ‘kidnapped’ by his classmates.”

A few weeks before, Natalie had been on a plane bound for New York. Also aboard was a college boy who had been forced to make the trip by some of his pals as part of a fraternity initiation. At the New York airport, reporters were waiting for the victim. When they spotted Natalie walking off the same plane they commandeered her. She was obliging and kissed the boy for the photographers; next morning her picture was all over the New York papers.

“I just happened to be there,” she heatedly said later. “I never saw the boy before, and I haven’t seen him since. I didn’t ‘plant’ him on the plane. I didn’t even know who he was or how he happened to be there until we landed at the airport and some photographers introduced us and asked me to pose with him. I was only trying to be pleasant and cooperative but the columnists made it look like the whole thing was an elaborate plot staged by me to get myself in the papers.”

It would appear that Natalie is the sort of person who just seems to gravitate unintentionally toward newsprint. Her widely renowned romance with Elvis Presley began as an honest mutual attraction between two young people. Could Natalie help it if the wire services from coast to coast echoed with the stories? Natalie was very sincere in her friendship with Elvis. As to its publicity value to her, she dismissed it with a shrug and a “who needs it?”

“This boy,” she said, “makes me feel like a little girl.” Her eyes were wide, and she sighed gently as she said it. It was very effective. For a while people were convinced that Love Had Come At Last to Natalie.

Then, abruptly, the romance was no more. Elvis was out with others; so was Natalie. In Hollywood in April, she told friends she had been forced to give him up because of the publicity. She said this with a straight face, and they believed she meant it. But probably she enjoyed the publicity while it lasted. Because in April she was gadding about with Nicky

Hilton, who has never been noted for his ability to keep off the front pages.

“Nicky,” she said, “is sweet.”

But more interesting than whether or not Nicky Hilton Will Find True Love is what makes Natalie Wood tick and whether or not she is going to find personal happiness along with artistic success and if so, how she is going to do it.

Some of the answers to these questions are supplied by a friend who has known Natalie for more than a year. “I am occasionally appalled by her behavior,” he says, “and sometimes bewildered by it, but I am completely fond of her. Under that bright little face is an interesting, if immature, mind. When I first met her, I was bored. She impressed me as another mass-produced Hollywood star, brittle as a plastic toy, with the emotions of a windup doll. Then, after an hour or so, some of the coating began to fall away, and after two hours, I became genuinely interested in her. As a person, she shouldn’t be underestimated.”

For another thing, Natalie possesses notable courage and candor. She does do many things for the sake of publicity. She does whatever her studio asks her to do for this reason. But she is not so overwhelmingly sold on the worth of publicity as to let false reports about her go uncorrected.

For example, one day last year, a columnist printed an item saying that Natalie had gone out to dinner with John Ireland, who at the time had just separated from his wife, Joanne Dru. The facts were that Natalie had been out for the evening with one of her regular escorts, Dennis Hopper, and another couple, and that Ireland had joined the party briefly. Natalie says, “I was furious. John Ireland! I’d never even met him until that evening. I called the writer. I told her it wasn’t true. ‘It’s libelous,’ I said, and I carried on for about an hour. Finally, she was as angry at the man who gave her the item as I was—he was a press agent for the restaurant.”

Most young actresses comport themselves in interviews as though they are walking on eggs. But Natalie is frank and she is refreshing for that reason alone.

A young actor friend of Natalie’s recalls an incident that points up her frankness. “Natalie was only fifteen,” he said, “and we were going out on a date. I said, ‘Where do you want to go?’ She looked at me and said, ‘Look here, I’m tired of saying where I want to go. If you don’t make up our minds for us, I’m never going out with you again.’ ”

There is another quality about her that stands out—her strength. In the eyes of some of her friends, the dominant aspect of her personality is her capability and her almost masculine will.

“This girl,” says Barbara Gould, a young actress who appeared briefly in “The Girl Can’t Help It” and who is currently working at 20th Century-Fox, “does everything by herself. She takes charge of any situation she happens to be in. Once we were going to Mexico on a holiday. I dreaded it—I didn’t know Natalie very well then, and I was sure all the arrangements would be up to me. I was very much mistaken.

“Natalie did everything. She was so efficient, I could hardly believe it. And she’s like that all the time. She handles herself and her entire family like a woman three times her age. She is so capable in any situation, it’s astonishing.”

Natalie has been the major factor in the support of her family since she first became a child star in pictures. “Not only that,” another friend adds, “but Natalie runs that family. She is the boss. The publicity people give the impression that she is just a starry-eyed, wide-eyed teenager, but actually she has the acumen of a diplomat and the financial mind of a Univac machine.”

That is not quite true. Natalie is actually rather casual about her personal finances. She frequently is caught without mad money. At other times, she becomes extravagant, as she admits frankly. “I go on these great kicks,” she said one afternoon. “Whatever I like, that’s what I do. For a while, everything in my life was horses. I even wanted to be a veterinarian. Before that it was ballet—I was determined to be the greatest dancer in the whole world. Then, for a while there, I was on a pink kick. Everything in my life was pink—my clothes, the drapes and the bedspread and the rug in my room, even a pink poodle. Now it’s all black. I wear black all the time. I don’t know what it is about me that makes me want to go the whole way. At eight, I knew more about horses than most racehorse owners; at ten, more about ballet than most dance directors. Whatever I do, I do it completely. I’m not satisfied with a little.”

“Does that include sex, too?”

She laughed. “I discovered sex at the age of three.”

That isn’t quite true. Actually, she was thirteen when she began going out with boys. Her parents protested her wearing lipstick and silk stockings, but she was determined to act grown-up off the screen. Her first date—she doesn’t remember the boy’s name—was with a young college student who drove her from her family’s house down the street to a drugstore, where they had an ice cream soda. Come to think of it, her first date was a good deal like her present dates. She still likes sodas, and seldom if ever has a drink of anything stronger. “Why drink? If I drink, I’m bound to feel bad and I won’t be able to work the next day. If I don’t work, I’ll be unhappy—and look at the money I’ll lose for the studio, not to say myself!”

This businesslike attitude is quite typical? In all business matters, she displays a shrewdness that amazes people who have been with her when she has been caught without any walk-around money. Last October, dining with a friend, she said she was considering changing her representative and becoming the client of a new agency. She had been dissatisfied with the way her agent had been handling her affairs. Now, this is a chronic occupational disease that afflicts all Hollywood actors and actresses at one time or another, but it was especially important to Natalie because at the time she felt she was on the verge of several important decisions and she wanted a sharp, shrewd bargainer working for her.

“I don’t know why she thinks she needs an agent,” one acquaintance said. “She’s her own agent. When she’s bargaining, she can be as tough as Irving Lazar.” (Irving Paul Lazar is perhaps the most successful literary agent in Hollywood, a man known for the fabulous prices he demands from studios for his clients.)

Another acquaintance says Natalie always gets what she wants. With that surprising candor of hers, she allows the truth of this statement. “I never had an allowance,” she has said, “but I always got whatever I wanted. At eight, I got a typewriter as a present for finishing a picture. At nine, I wanted a microscope, and I got that. Then I wanted a pogo stick, and I got that.” She paused, and some of the determination came through. “But,” she said, “it was my money.”

Still, there is a paradoxically meek side to her nature. In her relations with her parents she often seems like a typical teenager. Her mother frequently waits up for her to get in at night and, on a date, when the evening begins to wane, Natalie glances frequently at her watch. “I don’t like to worry my mother,” she says, “she might be waiting up.” Such times provide the only opportunities she and her mother ever get to talk. Usually Natalie is out of the house early in the morning and stays away all day long. Her life is a full one. When she is not actually working on a picture, she is reading scripts or going off to interviews with directors or studying, studying, studying. And when she is not working or studying, she is carrying on a social life that would make the Duchess of Windsor’s engagement calendar seem barren.

Natalie has been on dates, during the past few years, with virtually every eligible male in Hollywood, young or old, successful or aspiring, brilliant or tiresome. Her mother has not always approved of her choice of escorts. Nor has the studio. That has made little difference to Natalie, who since a tender age has been living a life that is almost exclusively her own.

Or so she would like to think. In many ways she is a rebel without a cause. She has not yet found out what satisfies and rewards her personally. In this respect she resembles millions of her contemporaries all over the world. Marsha Hunt has said, “She’s terribly sure she won’t ‘get it all done’ before she’s twenty,” and in that statement may lie the clue to Natalie’s personality at present. She is still far from grown up; she has the same self-doubts and anxieties that badger all teenaged girls—and on top of those, she has a terrible earnestness about her career, a dedication that gives her very little time for serious introspection.

“Sometimes I think I understand myself, sometimes I don’t,” she confided to a friend one day. “For the past couple of months I’ve been trying to find out what it is I really want—and I’m more confused than ever. It’s this way—one week I hate Hollywood and the phony life here, and the parts I play, and the people I go out with and even the palm trees and the sunshine. I think I’ll die if I don’t get out of it.

“Then something will happen—I’ll get a new part, or meet a new boy, or something else nice will occur and bingo! I love Hollywood, I love the people, I even love the smog.”

She paused. “I don’t know which side is the real side. I don’t know which me is me. Sometimes I want to chuck my movie career and go and work on the New York stage. That might be more satisfying. And yet I like the idea of being Natalie Wood, the movie star. It’s really fun. I don’t know if I would enjoy being a nobody in a bit part on the New York stage.”

Natalie had been offered the part of the young girl in “The Diary of Anne Frank.” the Broadway hit play. She wanted it very badly but her movie contract made it impossible for her to accept. Susan Strasberg won the role, and Natalie had been deeply disappointed (but she is hoping to have a crack at the part when the film is made).

“As I see it, the main thing I have to find out now is what every young girl has to find out—what satisfies me and makes me happiest. Maybe it’s working in pictures, maybe it’s doing something else. Maybe—although I doubt it—it isn’t acting at all.

“Meanwhile, I’m restless, moody, and unhappy . . . well, part of the time, anyhow.”

Despite her inner torments, Natalie is certain of one thing. Right now, she is planning to be the best actress she can be. On the set of “No Sleep Till Dawn” she won the respect and admiration of such seasoned performers as Karl Malden and Marsha Hunt by her professional behavior. “She was always letter-perfect in her lines,” Marsha recalls, “and she was always on time and ready. She went through all the scenes as though she had been acting all her life—which, come to think of it, she has.”

Malden said, “She’s a fine young actress. I enjoyed working with her.”

People have been saying that about her since she was small. The first person who said it was Irving Pichel, the director, who discovered her when she was four and living in Santa Rosa, California. Actually, Natalie discovered Pichel. The director was there on location, making a movie called “Happyland” with Ann Rutherford and Don Ameche. Natalie’s mother went to watch the shooting one day and took Natalie along. While the mother was absorbed, Natalie went off by herself.

“I always used to do that,” she says. “I don’t know why. I always made friends with strangers, on trolley cars, in department stores, everywhere. It’s a wonder I wasn’t kidnapped or something.”

Some sixth sense must have prompted her to make friends with Pichel. She walked right up to him, climbed up on his knee, and began telling him a story and sang a song. Pichel was entranced. He thought she was the most appealing child he had ever seen, and told her mother so. “I will find a little part for her in the picture,” he said.

Natalie’s mother was dubious, and that night, when her father heard about it, he was even more dubious. He was not certain he wanted the child in a picture. The only one who had no doubt whatever about what she wanted was Natalie. She begged and pleaded and even began to cry and kick and scream. She got her way.

THE END

—BY RICHARD GEHMAN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1957

gralion torile

11 Ağustos 2023In the great design of things you get an A for effort and hard work. Where you actually lost me personally was first on your details. You know, people say, the devil is in the details… And it could not be more true here. Having said that, let me inform you exactly what did deliver the results. The writing is definitely really powerful which is probably the reason why I am making the effort in order to comment. I do not really make it a regular habit of doing that. Secondly, although I can easily see the leaps in reasoning you come up with, I am not certain of just how you appear to unite your ideas that make the final result. For now I will, no doubt yield to your position however trust in the foreseeable future you actually link your facts better.