Not Bad For A Country Kid—Rock Hudson

The girl who gets Rock will have to be able to cook a good old New England boiled dinner, all right. But she’ll have to make him laugh, too. Rock is Swiss-Irish, and the old Celtic sense of humor, if not exactly boisterous, is deep within him like a bubbling spring.

It’ll have to be a girl who meets him a little more than half way, too. Rock is still being ribbed by his friends about Lana Turner. He had been in love with her from the first instant he saw her on the screen. He had even written her a fan letter. Finally, he met her on a sound stage. What did he say? “Nice to meet you.”

The only serious romance Rock has been associated with in Hollywood is, of course, Vera-Ellen—and for a guy who looks like Rock Hudson, that’s really staying out of mischief. Of Vera-Ellen, he says, “She’s a very cute girl.” As to why nothing came of the romance, he explains, “We planned to elope without telling a soul, but we never set a date for it. I guess the date never arrived.”

Rock, being twenty-eight, claims he can wait a few years before settling down to the “one” girl. Actually, Rock is as cautious as the sheriff after those cattle-wrestlin’ varmints, where girls are concerned. Maybe he’s afraid he’ll pick the wrong one, so he is still a little hesitant about marriage. But more than anything, I know that Rock loves a home. And when he settles down to one, it will be a good one.

In the meantime, Rock Hudson isn’t worried about anything, having already learned that almost everything, including love, comes with time—the right time, when you are ready for it

One small warning to Miss X, who will someday be Mrs. Hudson: keep a well stocked pantry and refrigerator at all times! Rock has the biggest appetite I have ever seen on man or boy, in keeping with his size. He can eat your dinner, his, and a third person’s. I have described him as being able to eat a ton of ice cream and twenty pies, although that might be exaggerating—a bit. But Rock’s a big man with a big frame.

I remember one day in London when a little English girl coming toward us on the Strand squinted upward, head tilted way back and said, “Blimey—that’s not a Rock, that’s a bloomin’ cliff!” I had to put my own head back, too, to roar. There, six thousand miles away in London, an equivalent of our own American bobby-soxer was saying exactly what I had thought the first time I laid eyes on him—the first day Rock Hudson walked into my office.

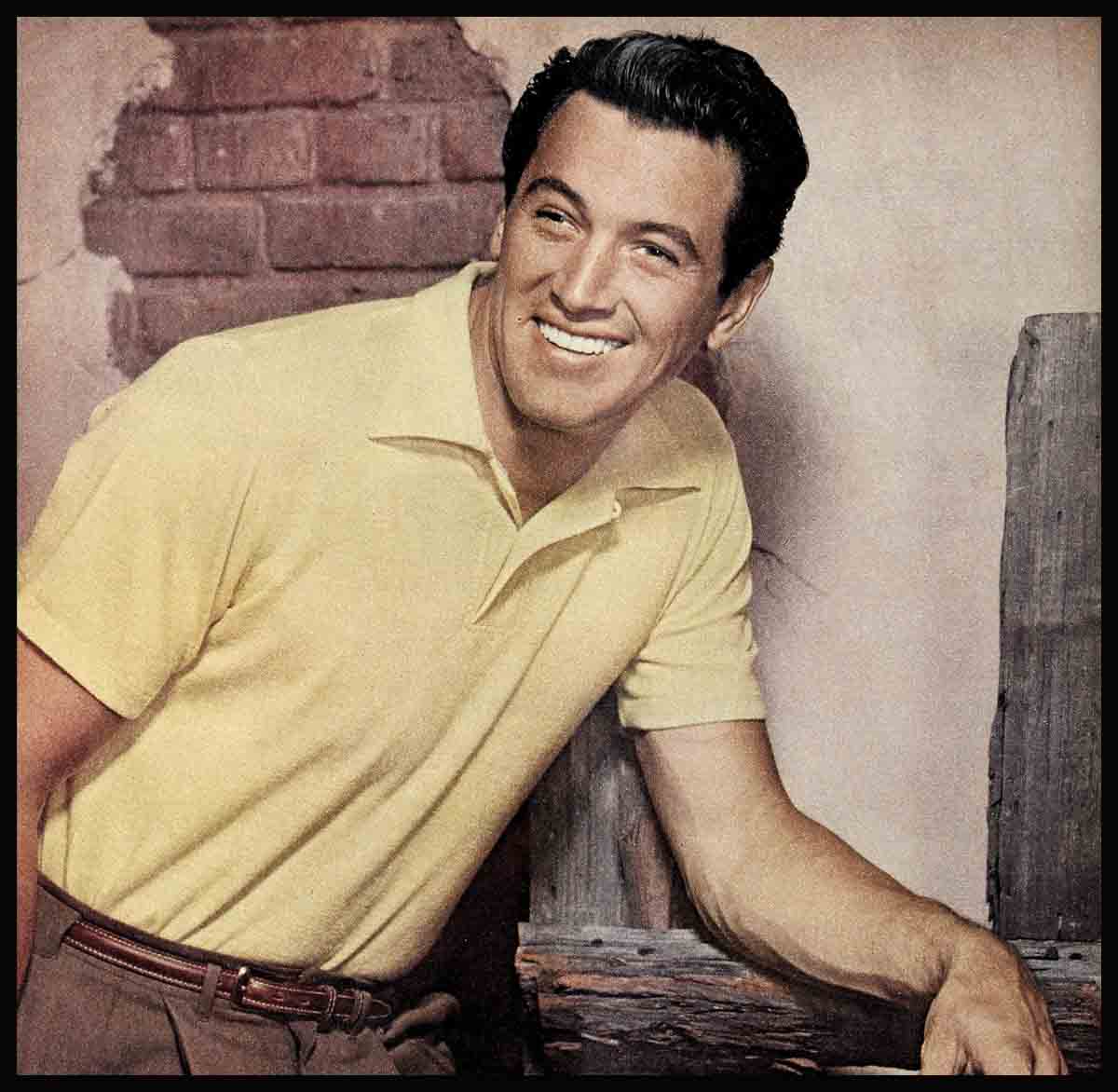

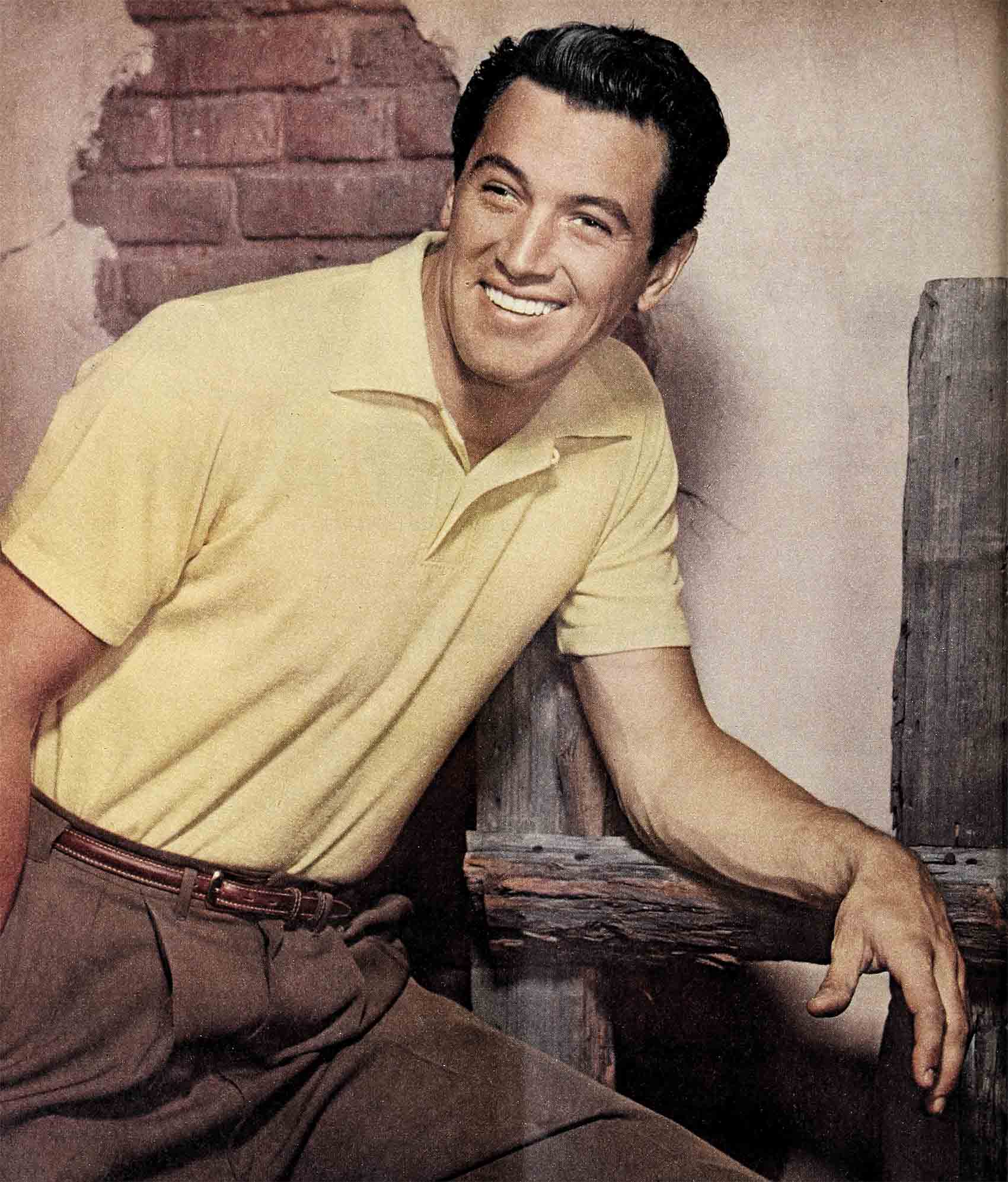

Only then, I couldn’t capsule it as nicely as our little British friend. The name tossed at me by agent Henry Willson, who brought him, sounded like Roy Fitzgerald. The name didn’t matter. But the guy did. What Willson had in tow was a young man unusually endowed with nature’s assets—six feet four, with the kind of facial structure a camera loves to explore. His dark hair was carelessly tossed . . . precisely the sort of thatch women like to run their fingers through.

“Green,” I commented to myself, “but with possibility.” His bashfulness and the look of wonder in his brown eyes cinched it. Standing in front of me was perfect Western fodder, if ever I saw it in my thirty-six years in motion pictures. Even if he couldn’t do anything, he’d add to the scenery just standing around. Then I heard a sound, like maracas. No one was doing a rhumba; it was just the young man’s knees knocking.

“Do you ride horses?” I asked him.

“Sure,” he.answered. The actual fact, that he hated horses and they hated him, came out later. At the moment I was directing “Fighter Squadron,” which had to do with planes, not equines. So I put him in with the other hot pilots.

He had only one line to say. It was “You’d better get a bigger blackboard.” I can hardly forget it, because it took thirty-eight takes to get it right. I glared around my eye patch (which, since my loss of an eye to a Western many years ago, seems to have become my trademark) but I had to keep my mouth shut. Hadn’t I cast this character myself—besides having him under personal contract at $125 a week?

I also made a test with him. That turned out so well that Bill Orr, then casting director for Warners, wanted to put him in my next picture, “Colorado Territory.” But the studio wouldn’t give him the sizable part unless I turned him loose from our contract. I didn’t do that, but I did take him along to New Mexico. “It’ll give you a chance to do some riding,” I told him, wondering why he turned green.

At first, it was strictly a struggle between Rock and horses, whom he regarded as his sworn enemies. But he got up at four in the morning with the wranglers and had coffee and beans. He not only helped load the quadrupeds into the trucks, he was soon riding them like the Indians. There was one note of insult added to injury. When the exhausted guy fell asleep one day, a jealous gelding chewed up a liberal helping of his mane.

A lot happened between the time Rock earned his saddle sores learning how a Western is made and the incident of the teenager on the Strand. There we were in England. where I had brought him to make “Sea Devils.” By chance, it was the time of the Royal Command Performance. And here was Rock—being presented to the Queen. Not bad for a country kid from Winnetka! When Her Majesty asked him about the picture he was making, tears came into his eyes.

But the events that preceded Rock’s appearance were not so poignant.

White tie and tails are obligatory, but naturally Rock had never owned such a rig. Well, others rent them, why not Rock? The only fly in that ointment was there just wasn’t anything available to fit his physique. Rock couldn’t even get into a sleeve. With that meticulous British tailoring, it takes two months to turn out a set of tails, and this was two days before the Performance. But studios, even abroad, have a way of getting things done. Somehow they shanghaied a couple of tailors, and I think they locked them up with cloth. needles and thread.

When Rock grins, he’s at his best. And there stood Rock, more like a cliff maybe, like the girl said, on the stage of the Empire Theater in Leicester Square—grinning at the hand he was getting. Every actor who is invited to the Command Performances introduces an act; Rock was introducing Walt Disney’s “Snow White,” and he did it so well I admit pride swelled out my own stiff white-shirted front.

After the show, the guests assemble in the large foyer upstairs—to be “received” by the Queen, Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Princess Margaret, assorted title holders and the Ladies in Waiting. A chap over a microphone tries to keep the others posted on what’s going on. Rock Hudson is still not noted for making much small talk, but what came over that mike went like this: “Her Majesty is now shaking hands with Mr. Rock Hudson . . . I say, Mr. Hudson has evidently made a witticism, the Queen is smiling . . .”

Universal-International tells me that Rock’s fan mail now runs about 7,000 letters a month. It seems to be a universal feeling (and I don’t mean the studio I so haphazardly sold Rock’s contract to!) because the feeling for Rock was just as big in Europe, too. From London to the Isle of Jersey, to Brussels, where he attended the Film Festival and was treated like royalty. himself—the fans followed him around. They followed him day and night, in fact—and there was nothing Rock wouldn’t do to sign an autograph. Once, when the doorman at a theater shooed his “faithfuls” away, Rock walked around the corner, where they followed.

The trip to Europe was a wonderful experience for Rock, where he saw another side of the world and rubbed elbows with prominent people. A bevy of British beauties showed him the social side of London. But Rock is still far from a magpie. Like other strong, silent he-men, he just doesn’t talk unless he has something to say.

There is still something of the overgrown boy in Rock, but if he seems bashful, he is certainly not backward. If he gives the impression of being shy, he can also warm up to you. Rock is very easy to handle, if you get to know him. He’s not temperamental, only nervous because he wants to get it right, which makes him work too hard at what he’s doing.

I believe that the old trouble, his knees knocking together, still comes back when he thinks about that test. When I signed Rock, I was under exclusive contract, with two years to go, at Warners. I couldn’t use him at the studio, and I couldn’t make an outside picture with him, so while Warners was wondering what to do, I turned my pact with Rock over to U. I.

Rock sat up all night with me to coach him, and pots of coffee to keep us awake, while he studied for the test he was to make there. When he got to the studio the following morning, shaky but at least sure he knew his part, he found he had been given the wrong script! In Rock’s condition, that was enough to make anybody call for the smelling salts. He did the test, from a new script he had never seen before. There were other tests, too, of which Rock says, “I run ’em sometimes, and I get the knee shakes all over again.”

Time galloped along. And so did Rock through various parts. When the fans besieged him at a couple of personal appearances, the studio decided he was too big for small parts, but wondered if he was ready for starring ones. That was when I found myself at Universal, too.

It seems only fateful that I should have directed Rock’s first starring picture. The studio sent me some scripts, from which I was to choose one for Rock. I picked “The Lawless Breed”—in which he ages almost twenty years. I had no qualms about it; like a thoroughbred, Rock needs handling by someone he is familiar with.

Rock is restive working with strangers; so we kept the cast right in the family.

Rock did all right after that, too, with Budd Boetticher as his director, in “Seminole.” And when I was to make “Sea Devils” in Europe, of course, I wanted my boy. The studio loaned him to RKO so I could take him along, and the co-star was Yvonne DeCarlo, with whom Rock had worked in “Scarlet Angel.” Recently he’s made “Back to God’s Country.” And now I’ve guided Rock through his first 3-D picture, “Gun Fury.”

With the bashful boyishness, Rock has a poise of maturity that is coming out more and more on the screen. He backs it up in person, too, because Rock is a boy who can take care of himself. He has the stuff of cooperation, and you can’t make pictures without that. When he insists on doing his own stunts, he winds up doing them all.

In the South Pacific, he wound up with what he considered the best job in Uncle Sam’s Navy. Where? In the laundry department! Rock explains it this way: “The cooks have to have their white clothes washed, so you just tell ’em if they want better service, they better furnish you with plenty of food—to keep your strength up!”

There is one annoyance he feels might take care of itself by quietly expiring of old age. That’s the story that before Rock got into pictures he was a mailman. “Not true,” insists Rock indignantly, “I was a truck driver. It’s true I carried the mail for a few months in Winnetka, but that wasn’t how I got into movies.”

Not that Rock has anything against mailmen. But he’s just stubborn enough to like the truth. And the truth is that he came to California after his Navy hitch and worked for a while in his father’s electrical shop. He had actually intended to go to the University of Southern California. But because a lot of other ex-servicemen also had the same idea, the entrance exam grade had been raised to a B-plus. Rock cheerfully admits he never made a B-plus in his life. So he started driving a truck, hauling beans.

Rock thinks now maybe it was all for the best. Because when he had some pictures taken, a friend sent them to a radio producer. The pictures wound up with Willson, who brought Rock to me.

I have the feeling that maybe I should have just held on to that contract, because I think Rock is of the stuff from which we will get our future Gary Coopers. The future looms ahead of him as big and wide as his shoulders. And while I don’t have just held onto that contract, because of knowing I can always feel, “That’s my boy, Rock.” It’s a great feeling, because he is really a great guy.

THE END

—BY DIRECTOR RAOUL WALSH

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1953