What Happens When A Young Girl Is Rushed Into Womanhood?

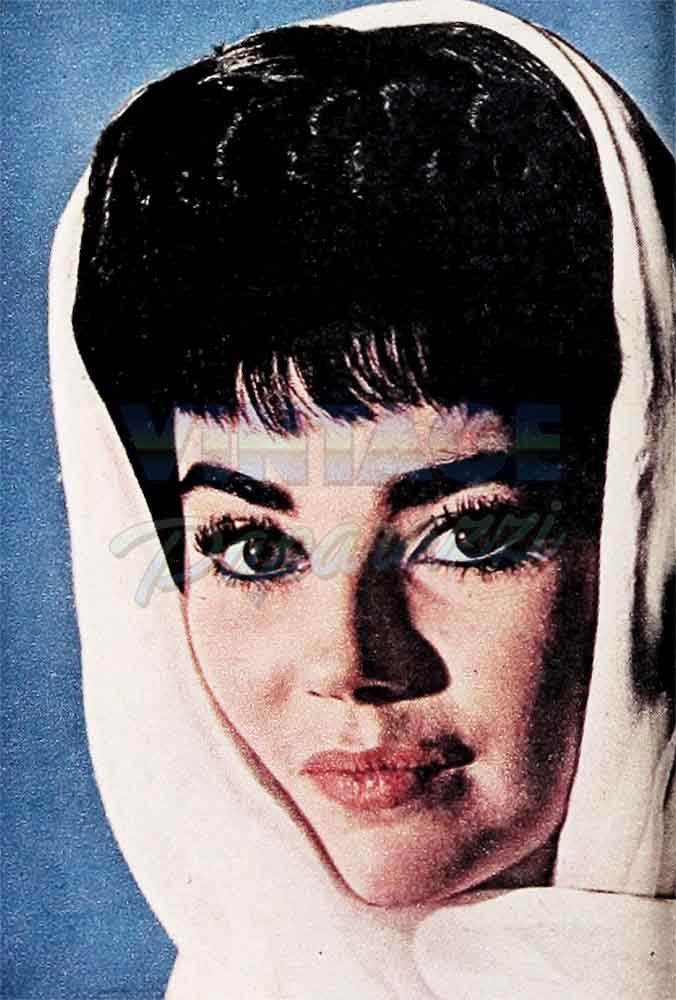

Brigid Bazlen finished her role as a saddle tramp in “How The West Was Won,” caught the first plane and hightailed it home to her mom in Chicago. That’s what she does whenever she has even a few days off. She’s not quite ready to grow up just yet and she is candid enough to say so.

Brigid has never dated in Hollywood, she doesn’t want to. She’s more comfortable with young Stormy MacDonald, the Zenith heir, whom she’s known “forever” and whom her mother gave a couple of bucks (Stormy’s always broke) to take Brigid to dinner the night before she sailed for Spain and her movie career.

A few weeks later, on a lavish sound stage, surrounded by all the glamour trappings, Brigid was doing one of the most sensuous dances of all time. She was Salome—a Salome with huge amber spider eyes, long slinky hair, the most sinuous hips in history and the face of a child. “Definitely sick,” she said of her own characterization. “An angel, this kooky girl, terribly smart, terribly bright, careful to appear sane—but crafty as only the insane can be.” What aroused Brigid’s sympathy was that Salome could be at once so young and so depraved, and she played the part pretty well for a kid who has just achieved sixteen, a junior at Chicago Latin, who’d cut her teeth and earned her Peabody award as “The Blue Fairy” on a kid’s program.

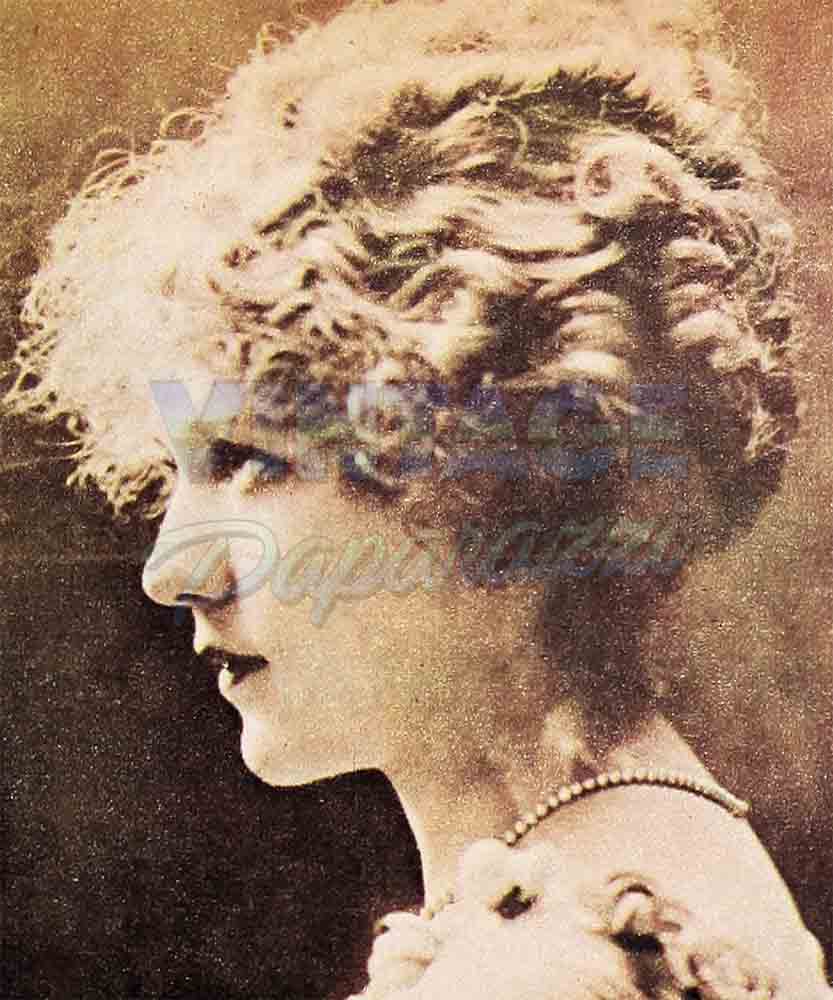

If I were casting Brigid I’d have cast her without seductive make-up and with those great eyes mirroring what only a sixteen-year-old can mirror—the gorgeous excitement and wonder of being alive. But that’s never enough for Hollywood. From 1909, when lovely little Norma Talmadge played hooky from Erasmus High in Brooklyn to appear in one-reelers at the old Vitagraph studio, movie-makers have pushed beautiful female children into the role of nymphs; directed them into flaunting charm of which they were only half aware; beguiled them much too soon into the vocabulary of sex, and rushed them into portraying loves they weren’t nearly mature enough to understand.

Elizabeth Taylor at sixteen, playing her first adult role as Bob Taylor’s bride in “Conspirator,” said honestly, “I don’t really know what I’m expected to do. I have the emotions of a child in the body of a woman.” She had never really dated, she was carrying on her long distance correspondence with Glenn Davis, in love with love. When she was supposed to be playing an adult scene, she was reliving the moment when she’d received (by mail, of course) Glenn’s “A” pin.

Loretta Young at fourteen, playing her first love scene, in “Laugh, Clown, Laugh,” was padded out in symmetricals to enhance her thin little fourteen-year-old frame. “Look into the mirror,” her director would say, “You see your lover, you’re mad about him, make it sexy. Okay, let’s go.” Loretta would nearly burst her chest trying to show emotion but the director, furious with the effect, would bellow through his megaphone and they’d have to try again. Finally Nils Asther, her lover, said, “Loretta dear, when you see me in the mirror, just imagine I’m a hot fudge sundae.”

And Jean Simmons, playing Ophelia, winced every time she opened her mouth. Her babyish rabbit teeth had just been filed down and the cold air “fractured” them. When Laurence Olivier tried to tell her how to read her lines, she committed the—for him—unforgivable sin. She giggled.

Seventeen-year-old Clara Bow had never had a date when she arrived in Hollywood. Seventeen-year-old Joan Crawford, then Lucille LeSueur, burst into tears because no one met her at the station. Seventeen-year-old Rita Hayworth was escorted to and from the studio by her father, and all the wolf whistles followed them to no avail. Seventeen-year-old Judy Garland wasn’t allowed to date and was forced to dress like a child. Seventeen-year-old Lana Turner wore a sweater, all right, but she’d never had any fun. But Natalie Wood, who at sixteen, had taken her high school diploma with straight A’s, was a show business veteran at seventeen—thought nothing of dating actors of twenty-five.

Never doubt this:

Playing love scenes on screen forces a girl into a woman’s role just as surely as a hothouse forces a flower into bloom. But when the little nymphs start taking on a woman’s life off screen, with no script writer to write the script—catastrophe strikes!

You have to be a teenager before you can become an adult, and these girls who’ve been robbed of their teenage eventually wind up in headlines as they reach out for life—for love—for security—for the woman’s life they’ve essayed too soon. That they’re insecure in their grown-up pose is reflected in the fact that one and all of these girls reach out for love, yes, but also for someone to reinforce and guide them.

Witness Mary Pickford, who married Owen Moore at sixteen, three months after rehearsing her first love scene with him for D. W. Griffith . . . Witness Clara Bow, who clung first to Gilbert Roland, then to director Victor Fleming, then to Gary Cooper, then to Harry Richman, then to Rex Bell . . . Witness Lana Turner, who married Artie Shaw on their first date when she was really in love with Greg Bautzer . . . Witness Joan Crawford, who married once out of sheer loneliness . . . Witness Jean Simmons, who at seventeen was trailing behind thirty-two-year-old “Jimmy” Grainger, ignoring the friends who advised her he was a “scoundrel,” that he’d been married and had two children, that he was far too old for her . . . Witness Greta Garbo, who at seventeen played Trilby to Mauritz Stiller’s Svengali and never even found moral sup- port without him . . . Witness Judy Garland, who fell for Dave Rose and Vincente Minnelli and Chuck Walters—always older, brilliant, talented men—in a desperate effort to find reinforcement and guidance . . . Witness Tuesday Weld, who couldn’t wait for love . . . Witness Liz Taylor, ditto . . . Witness Loretta Young, who ran away to Yuma on her seventeenth birthday and married Grant Withers, the handsome young man she’d just played love scenes with in “Two Lovers.”

This was the first in a series of romances that left romantic Loretta bereft. She didn’t know where the scene ended and life began. She was able to convey passion realistically on screen—all these girls have—but off screen they hadn’t matured enough as women to give a man the relationship marriage demands. Do the girls ever mature? Or do they forever “act” a love scene, forever reach out for some man to guide them?

Norma Talmadge had never dated until she was a star. Ardently courted by Bill Hart and a dozen other glamorous actors, she married a stocky Russian-born newcomer, Joseph M. Schenck, who for ten years produced her pictures and made her a star. “Daddy,” she called him and to “Daddy” she confided the ambition of her life. “I want to succeed!” she told the dependable Mr. Schenck one night, strolling along under the pepper trees. “I want to get to the top because I want luxury.” Within a couple of years she had luxury, she was collecting emeralds and diamonds like a child turned loose in a candy shop. From DuBarry to Camille, Norma played the great heroines, pitting herself against the world for love.

Norma once said. “Our constant association with romance on the screen makes love a part of our lives. We need it and the companionship that goes with it. Love is a different thing with us than it is with most people.” When she said that, she had been married to Schenck almost ten years, they were still called “Hollywood’s ideal couple.” But he was too involved in business to always give her the companionship she craved. More and more, Norma was seen with Gilbert Roland, whom she had picked from the extra ranks in 1925 to play Armand to her Camile. Roland was her constant escort, they traveled together to Europe and to Honolulu—but when Norma finally divorced Schenck it was to marry George Jessel. At that point she retired from the screen and prepared to enjoy life. During their five-year tempestuous marriage, Georgie made six transcontinental trips to win Norma back after temporary estrangements, finally lost her in divorce. (Norma joined her sisters, who had also been teenage actresses, in the divorce court. Natalie had just divorced Buster Keaton and Constance had just divorced Townsend Netcher, her third.)

Wed for love—finally

In 1946 Norma married a man whom she loved and respected—Dr. Carvel James, a navy surgeon and war hero. She had been his patient and then his lab assistant, before the war. For him she retired from the screen, still a very beautiful woman, and at last knew a woman’s life.

Mary Pickford, also retired from the screen, found her life finally with Buddy Rogers. Joan Crawford, after thirteen years alone, found hers briefly with executive Alfred Steele until his death. Liz Taylor knew a woman’s life briefly with Mike Todd and has been unhappily seeking such a life ever since his death. Jean Simmons seems to have found hers with Dick Brooks.

They were luckier than Rita Hayworth, who also married early and put her career in the hands of an older man. Rita had been dancing with her family from the age of six. By the time she was sixteen, the dark, chubby, beautiful senorita was rattling her castanets and stamping her flirtatious feet as dancing partner to her handsome dad, Eduardo Cansino, in the floor show at the Caliente Club, where he hoped she’d be seen by film executives. She was. Winfield Sheehan of the old Fox Film Company saw The Cansinos and offered her a film test. During that first year in Hollywood, Rita bicycled four inches off her hips, studied dramatics, practiced dancing with her father, appeared in six pictures—and dated no one. Shy, quiet, unambitious, she probably would never have made it save that her father took her by the hand to the studio every morning. “People said I was too strict, I should allow her more contact with men or she’d rebel.” Eduardo Cansino once said. “But she seemed quite content.”

Then one night Edward Judson, a suave, balding auto salesman as old as her father, phoned to say he’d seen her on the screen and could he take her to dinner? Within ten minutes he was at the house, chatting with her mother and father. and he did indeed take Rita to dine. During that first evening he convinced her that she could become a good actress. “It was warm, pleasant oil he poured in my ears,” she said. Edward Judson became her business manager, he selected her wardrobe, dyed her hair red. got her parts, demanded high salaries and “convinced me I was helpless without him.” The girl who had been fiery and provocative on screen from the first, now found herself married to a man who regarded her “only as an investment.”

Six years later Rita Hayworth began to chafe under the protection she’d longed for. She divorced Judson, rebelled against parental and marital sheltering and set out to become the gayest, dancingest girl in town—just as she was on screen. With Victor Mature she closed Ciro’s and the Mocambo. She dated Steve Crane and Tony Martin, David Niven, Howard Hughes and Orson Welles. To criticism she retorted boldly, “In Spain where my father comes from and in Mexico where I’ve lived, a girl’s worth is judged by the number of her suitors.” She announced her engagement to Vic Mature, but Vic went into the Merchant Marine and Orson Welles snatched her from her brief fling (less than a year) of freedom.

Characteristic of the poor little love goddesses seems to be a total inability to judge their lovers or the potential of happiness with those lovers. Rita adored Orson Welles, he was her mentor, but she couldn’t have weighed her chances for happiness with a man whose talent amounted to genius and who gave himself heart and soul to his own creativity. He only worked. he never played, he stayed up all night writing. The love goddess divorced him in 1947, shortly after “Gilda” was released and Rita became the most publicized girl in the world, the darling of the GI’s. She went to Cannes, hoping to see Orson and instead met Aly Khan, the gay charmer, the cultured prince. Not long after, she phoned her father.

“Daddy, come over,” she said. “I want you to meet somebody.” (It was a message reminiscent of the telegram Lana sent her mother the night she was married to Artie Shaw. “I’m married, honey. Love, Lana.” In neither case did the nymph mention to whom.)

Rita was “Baby Darling”

Had Rita studied the script she might have found flaws in her Prince Charming. He had, to begin with, an obligation to an empire. He also had a great flair for living, an unbelievable charm and energy galore. He drove his motor cars at a hundred kilos an hour, sometimes with his feet rather than his hands on the wheel. (When he died, it was at the wheel of a fast car.) Lovely women he found irresistible—even when he was married to Rita, said the rumors. Katherine Dunham, for example; Heidi Beer, wife of a European hand leader, for example; Nancy Masseroni, of Boston society, for example. Rita herself really had no taste for the lavish life and not for a moment was she equipped to handle her husband’s Chateau de l’Horizon as her mother-in-law, the Begum, handled the Aga’s household. “I will order, Baby Darling,” Aly always said.

There was no question that “Baby Darling” loved her prince, but she did not love his life, and a life is different from a movie script. It goes on and on and on. And one pattern marks the lives of all these once-teenage love symbols. Can you imagine them on screen without a man in the picture? Well, they can’t imagine themselves off screen without him, either. They must have a man, must find a marriage, they’ve never developed the muscles for standing on their own feet or quietly pausing to get their life back in focus. Natalie Wood jumped from Bob Wagner to Warren Beatty. Liz went from Todd to Fisher to Burton. Frantic for security, needing to he needed, dependent on the aphrodisiac they tasted too soon and found sweet—they throw themselves from one romance to the next.

Rita turned her back on her royal life and her royal prince and threw herself into blue jeans and slightly uncombed marriage to singer Dick Haymes. Haymes was broke and living in a lakeside cabin in Nevada. How Rita could have seen strength in him is a mystery. He was probably the most harassed man in the world at that point, he was being sued by numerous plaintiffs on financial matters, was fighting deportation to Argentina on charges of avoiding military duty, being sued for back income tax and bickering over his divorce from Nora Eddington. Perhaps little Rita felt that they were both victims of society, for she was fighting Aly over Yasmin’s custody and Yasmin’s financial settlement, there were rows with the studio and a charge of child neglect. But she clung to Dick for a miserable couple of years until she couldn’t stand it anymore.

After Haymes, producer Jim Hill. After her divorce from Hill, Gary Merrill. With Gary she has trotted barefoot and carefree, or bitterly bickering, around the world. One of the most beautiful women ever filmed, Hollywood’s Love Goddess, Rita Hayworth is living at the Chateau Marmont, at this writing. The girl Aly once moved into the Hotel Reserve near Monte Carlo into a suite draped in pink satin like the boudoir of a French empress, the girl he ensconced in his own palace, is now living in a small suite and she is alone. When she left Aly she said that essentially “I am a Spanish peasant. I’d like to work two days a week and run away with the children for five.” But her children are in school now, Yasmin in Switzerland. And her last picture “The Happy Thieves” was completed two years ago. You wonder what might have been the fate of Marguerita Cansino if she had not been a child dancer, if she had not won a movie contract at seventeen and started acting love scenes on screen before she’d ever had a date with some teenage boy.

You wonder what might have been the fate of Greta Garbo if she had married Mauritz Stiller—the one man who ever gave her true moral support—or if she had been able to work with him over a long period of time. She was seventeen and Stiller thirty-nine, when they met. He taught her how to read, how to dress, how to think, he directed her so relentlessly before the camera that she sometimes ran off the set screaming that she hated him. But of course that wasn’t true. She has said many times, “He willed me to do as he wished. Everything I have ever done I owe to him.” He was the one who took her out of the Royal Dramatic School in Stockholm and gave her her chance in “Gosta Boerling.” He brought her to America, intending to be her director—but things didn’t work out that way. After ten days on “The Temptress” he was fired, and Greta distraught. “I thought the sun would never rise again,” she says.

When Stiller died, she still kept him in her consciousness, “Moje says I must do this. He doesn’t want me to do that.” Symbol of glamour on the screen, often a lonely woman off screen, what would have happened to Greta Garbo if she had had no dramatic aspirations? If she had not plunged at seventeen into a world where she competed with men on their terms and simply exhausted herself emotionally?

Clara Bow, the “It” girl

You wonder what might have happened to Clara Bow if she had not become the toast of the 20’s, the symbol of flaming youth, the “It” girl, the symbol of sex. In 1928 there was nothing to match this girl’s popularity, she was receiving twice as much fan mail as Valentino. She’d been a high school kid from Bay Ridge, Long Island, who entered a magazine beauty contest—a little tomboy who’d been a darn good baseball pitcher but had never been to a party or a dance. Her mother loved her with a strange bitter love, and was so opposed to a movie career that she felt it her duty to kill Clara with a butcher knife (she actually made the attempt) to keep her from taking her first part in “Down to the Sea in Ships.”

Tomboy Clara had never been in love, never known romance, until she got to Hollywood and started making “B” pictures with a jazz age background. Gilbert Roland was on the same lot (not yet discovered by Norma Talmadge) and he and Clara fell in love. “ ‘Clarita,’ he called me,” Clara says. “He still had a Spanish accent and we used to dream of being married and dream of the time when we’d both be stars. I don’t know what ever separated us. I adored him. There was one wonderful year, then he was working hard on one lot and I on another, we were both terribly jealous and everyone seemed to come between us. We had one violent quarrel, I certainly didn’t dream it was final but it went on and on and after that we were each too proud to make a move. I ran wild, trying to make up for all the starved years of my childhood. I’d have gone haywire without Victor Fleming, who directed several of my pictures. He steered me straight. I began to read, to enjoy music, grow calmer, even happy.”

But Mr. Fleming was a good deal older and gradually their romance developed into a close friendship. Then Clara made a picture, “Children of Divorce.” Gary Cooper was cast opposite her in his first big part—and during rehearsals, even before the cameras started turning, they were in love. “It was wonderful and beautiful while it lasted,” Clara says, “but it’s difficult for a motion picture star to marry. Gary was so jealous.”

And Clara went on and on. Bob Savage, the millionaire playboy, cut his wrists for her . . . The wife of a handsome Texas doctor sued for alienation of affections . . . There was Nino Martini and Bela Lugosi. And Harry Richman. whose New York girl friend, Flo Stanley, told the press, “Harry’s my man. He doesn’t love that little kid. He’s only playing with her for all the publicity he can get out of it.”

The press criticized Clara as today they criticize Liz. “She’s still behaving like a headstrong school girl, allowing her emotions to gallop off with her good sense,” they wrote. No one stopped to realize that of course she was acting like the school girl she’d never had a chance to be. She was the “It” girl. Elinor Glyn wrote the story for her and Clara believed it. She played the “It” girl and lived the “It” girl until the era of flappers ended—and with it her phenomenal popularity. She never came close to a woman’s life until she married Rex Bell and retired from pictures. Today the “It” girl is still pretty but in delicate health; she lives in a modest cottage with only a nurse companion. At the height of her fame as a love symbol, a discerning pen wrote, “Clara has everything but love.”

Like Clara, Lana Turner had a childhood marred by violence. When she was ten, her father was blackjacked by thugs and dumped in an alley to die. After that, Lana and her mother were poor, and Mrs. Turner’s health was bad.

Julia Jean Mildred Frances—later, Lana—spent a number of years in a convent. When they came to Los Angeles and she went to Hollywood High, she just didn’t care much for school. And then suddenly she was in movies—America’s sweater sweetheart—dashing from nightclub to nightclub, trying to cram into this minute all the fun she’d never had and up to her pretty ears in a torrid romance with twenty-seven-year-old Greg Bautzer. He was her mentor, a gay dashing lawyer whom Lana adored; they were engaged, but Greg was altar-shy and as Lana herself says ruefully, “I’ve always been a dead duck for a guy who’s hard to get.”

Lana said, “I was really hooked. Greg was the first man I’d ever loved and so Help me, every woman remembers her first love! But one night on my mother’s birthday Greg broke his date with the two of us, and I was furious. When Artie called and asked me to go for a drive, I went.”

Artie, of course, was Artie Shaw, with whom she’d just made a picture and whom she hated—she’d said so in print. Her mother also detested Artie and had said so. But somehow, as they drove along in the moonlight and Artie told her about the little house with the white picket fence and lots of children . . . “They were all the things I’d dreamed of having with Greg, only Greg wasn’t going to marry me. When Artie took my hand and asked me to marry him, I said yes.” An hour later they were on a plane headed for Las Vegas. She was still wearing Bautzer’s ring.

“Doesn’t it make you sick?” Lana says today. “Now do you understand why my friends tell me I’m the hokiest broad in the world? Well, at least, I can laugh at myself.” And she still tries to.

Four months later the Shaws were divorced. Lana was eighteen, still a child with a child’s values, and she went out looking for love. She was totally unpredictable. She’d fail in love one day and not see the guy the next. Once a press agent spent five hours talking her out of marrying a radio announcer she’d met a few hours before, and then spent a week trying to keep the radio boy from killing himself over lost happiness. But for Lana there was Victor Mature and Tony Martin, Tommy Dorsey and Howard Hughes. Then a month’s glamorous whirlwind courtship and she married Stephen Crane.

The ceremony was performed by the same Justice of the Peace at Las Vegas who’d married her to Shaw. “This time please tie a knot that will stay tied for keeps,” Lana implored him. And she meant it. She wanted a husband, she longed for children. Then she discovered that Steve had neglected to obtain a valid divorce from his former wife. Their marriage was hastily annulled but soon after, when Lana discovered she was pregnant and when legal technicalities were cleared away, she and Crane remarried. The headlines never ceased exploding. Lana’s baby, Cheryl, was a blue baby because of an Rh-negative factor in Lana’s blood and the struggle for the child’s survival is a nightmare that Lana has never lost. Six months later, her marriage blew up and headlines screamed the news of Steve Crane’s attempted suicide.

And Lana kept reaching out. There was Turhan Bey, then Tyrone Power. This time she said. “I’m seriously in love for the first time. I was young before, I made all the teenage mistakes other girls make, but I grew up in the spotlight where everything I did was magnified. Now I’m in love and I hope to marry.”

She never did marry Tyrone Power. After his death she discussed the matter for the first time. “I loved Tyrone Power in a way that I never loved anyone in my life,” she said. He was in Europe making a film and Lana flew to New York to meet him. The next thing she knew, she received a call from Palm Springs. He hadn’t been able to stop in New York, he’d been summoned by the studio. When Lana flew west—which she did immediately—she never left the airport. Tyrone met her there—and he had changed. Lana feels that he was told lies about her by someone who claimed to be her friend. Lies or no lies, Linda Christian had moved in.

Lana’s name was coupled with Sinatra’s, with Fernando Lamas’, with Bob Topping’s. In 1948 she married Bob without loving him, but with a tremendous respect for his powerful personality. After that, she married Lex Barker.

“Let’s be honest, the physical attracts me first,” she has said. “Then if you get to know the man’s mind and heart and soul—that’s icing on the cake. But the first thing that brings a man and woman together is physical, and anyone who denies it, if you ask me, is a liar. . . .”

Just like a movie script. It’s a very young and naive attitude and it’s gotten Lana in plenty of trouble. It brought into her life a thirty-two-year-old ex-marine with underworld associations, Johnny Stompanato, who was killed in Lana’s home one spring day in 1958 by a knife wielded by her then fourteen-year-old daughter.

During the ordeal that followed, Lana Turner grew up, people said. But her marriage to Fred May, which seemed to make her happy, ended in divorce. She still sees May, she is friendly with him, but the fact remains they’re divorced.

Lana’s heart goes out to Liz Taylor at this moment because like few women in this world, she understands what Elizabeth has suffered, how desperate she’s been for warmth and security, how miscast most of Liz’ lovers have been. Lana and Liz have this in common: when they can’t get what they want, they grasp at frantic alternatives. With Liz it was Nicky Hilton after the Bill Pawley romance went on the rocks; Eddie Fisher when death snatched Mike Todd; Dick Burton—because he was there.

A teenager’s first awareness of love is a physical attraction, the goodnight kiss. A normal teenager falls in love but keeps growing and falls in love again. She doesn’t consider herself ready for marriage to the first boy who comes along. Teachers and parents suggest caution and gradually, as a girl matures, she goes to college or gets a job. She discovers that sex isn’t enough, a man must have strength, an intellect and a personality that jells with hers. Kissing is great, physical attraction is great—but it isn’t enough. That’s how a normal teenager behaves.

But the teenagers who become the passion flowers of the screen bloom too fast, they love too fast. They plunge into the mad whirl of Hollywood nightlife. They date every eligible beau and some not so eligible. All too often they find themselves with a string of broken marriages before they begin to understand the nature of love.

Natalie Wood seems to follow the pattern. There were Scott Marlowe and Martin Milner, Tab Hunter, Dennis Hopper, Nick Adams (to whom she was rumored married), Bob Vaughn, Jimmy Dean, Elvis Presley. (Elvis with Hollywood still a dream ahead was asked what he’d most like to do if and when he ever got to Hollywood. He said, “I’d jus’ like to date that Natalie Wood. I read about how fickle she is and I’m fickle, too, so we should get along jus’ fine.”) But Natalie wasn’t fickle. She was a rebel and she had a cause. What she wanted and needed more than anything in the world was love. “I don’t know how people can exist without love, far less work without it,” she said as she swooned altarward with Bob Wagner. And she’s still chasing love, still reaching out—this time for a man who isn’t altar-bound.

Tuesday Weld started out the same way, dating every boy in every picture, dancing the fastest, laughing the loudest. She was fifteen when she came to Hollywood and within a year she’d kicked over the traces. She was getting the reams of publicity that go with a Clara Bow or a Lana Turner—or a Tuesday Weld. Then she met Gary Lockwood and for a year it was only Gary Lockwood. It was a different life, a life of quiet dates. They cooked at her house in the hills, they spent days on his little boat, then the romance cooled.

Tuesday isn’t rushing into marriage, maybe she’ll still beat the rap that follows little-girl loves. “She’s smart enough to realize that happiness is better than nonsense,” Gary said when they were inseparable. “I’ve seen her have more fun on fifty cents than anyone else could have on fifty dollars.”

And Tuesday said then, “He understands me, I never wanted most fellows to under- stand me. You can’t just sit down with someone one night and say this is how I am. They have to see you in action over a period of time, know you little by little. For this boy I’m willing to spend the time. He’s a rebel like I am.”

Rebels against society. Rebels against parental authority. Rebels against studio authority. Read through the histories of the hothouse blooms and you’ll find the pattern. Mary Pickford disobeyed her mother in marrying Owen Moore, Lana disobeyed hers by marrying Artie Shaw, Loretta rebelled and married Grant Withers (her mother tried to have that marriage annulled). Judy Garland married Dave Rose to get away from Mama, Rita married Judson. Liz Taylor asserted herself after she divorced Nicky, Natalie asserted herself after she divorced Bob (her mother was hoping until the last that she wouldn’t divorce him).

They are passionate and willful, they break hearts including their own. They live too fast and think too little and give themselves and everything they have to love. But they don t know—for certain—just what love is.

Brigid Bazlen isn’t having any, thank you. She’s a little luckier than some, she has a mother who is hep—a talented columnist and fashion commentator. Brigid comes from a family of talented writers, her aunts have all won distinction, so what’s so new about a girl with a career? She was brought up with definite standards of taste in clothes, in literature, in living.

Salome or not, Brigid is not ready to bloom Hollywood style. She goes home when her picture is finished and leads a teenager’s life. She’s afraid of the Hollywood rush, the hothouse bloom that leaves you a swinger, yes, but with a cold, cold and often empty heart.

—JANE ARDMORE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1963

No Comments