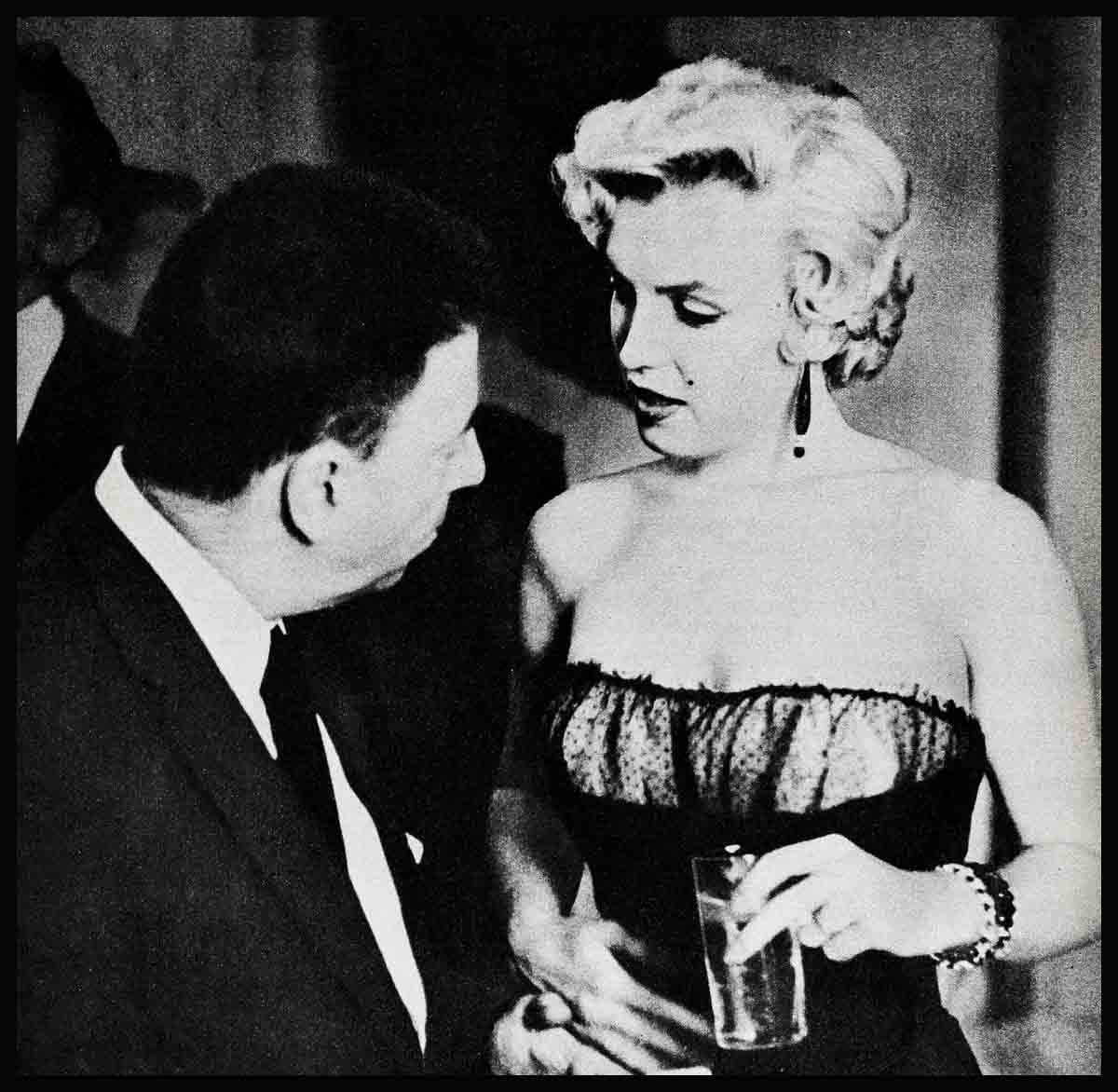

The Things Marilyn Monroe Said To Me!

My conversation with Marilyn Monroe took place in her New York apartment—in her bedroom . . . her all-white bedroom.

It happened like this. She had been busy getting dressed in a white sweater and black velvet toreador pants, while I had been waiting in the sunken living room. Then suddenly people began arriving. More people than could conveniently be kept quiet during an interview.

“You’ll have to interview me in my bedroom,” Marilyn said to me.

I agreed—not too reluctantly. There being no empty chairs in the bedroom, I was invited to fling myself down on the bed—shoes and all—atop the pink taffeta bedspread.

Marilyn pointed out to me that I was in very good company, as far as gentlemen were concerned, for above her bed hung a painting of Abraham Lincoln. On her night-table was a celebrated photograph of Albert Einstein, taken by Milton Greene, vice-president of Marilyn Monroe Productions. Also on the night-table was a book, “Selected Plays of Sean O’Casey.” Over in a corner was a hair-dryer.

While I was in the living room I had been impressed by the library of good books—several on art and painters—and several paintings, one of Marilyn herself, by Jean Negulesco, a Hollywood producer and director who had managed to paint only Marilyn’s face. Anyone who looks at Marilyn and doesn’t see the rest of her certainly is different.

Marilyn talked to me in the breathy way that all the other sexpots imitate.

She was on the verge of her Hollywood comeback and, as a reporter, ventured to remark: “I hope the year away from Hollywood didn’t give you any highfalutin ideas and that you’ll quit being sexy.”

“I’ll never quit that!” she promised in a sexy gasp. “But put it ‘exotic,’ will you, instead of sexy?”

Exotic, sexotic—whatever she wants is all right with me. Still, in “Bus Stop,” her first Hollywood picture to be made under her new deal, she plays a night-club singer with a wiggle-waggle in her voice. And in “The Sleeping Prince,” which she’ll do in London—with none other than Sir Laurence Olivier, knighted for his great acting by the King of England—she plays a chorus girl with a lot of zing and zang in her walk. Sex shall not take a holiday on the Marilyn Monroe calendar which we all know so well.

“Where will you be living in Hollywood?” I dared to inquire.

“We’re talking about maybe I might get a house with Amy and Milton and Josh, their baby—little Josh. He’s very fond of me and I of him.”

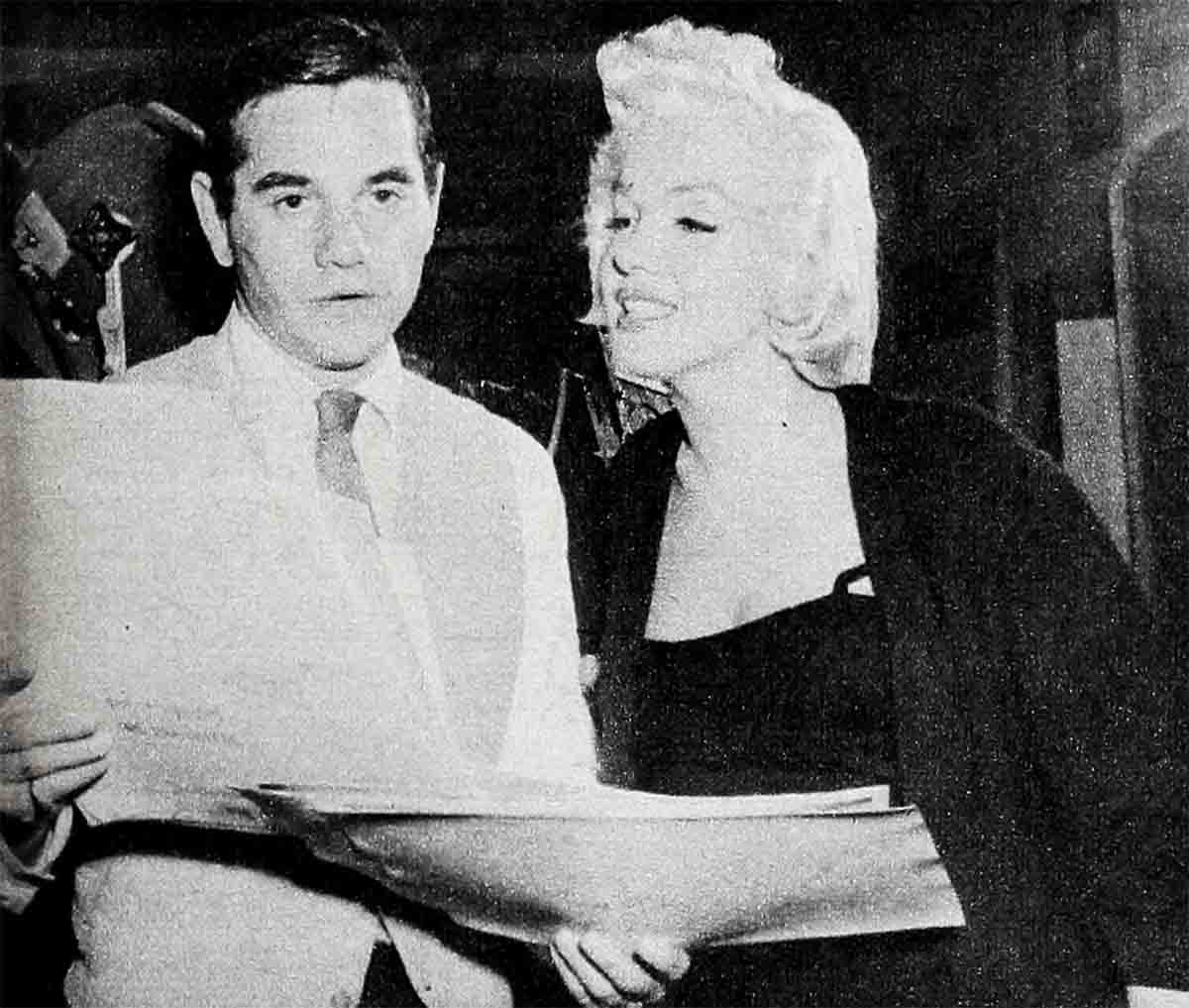

She was referring to Milton Greene— who guided her in her successful bolt from 20th Century-Fox—and his cute, 98-pound wife and their child.

“How long will you remain in Hollywood this time?”

“Probably till June 1.”

“And then—England?”

“That depends,” Marilyn said. “We don’t know yet when we’ll be doing “The Sleeping Prince.’ We think we’ll get started in August, and are so delighted to have Sir Laurence Olivier as my leading man and director. He’s my dreamboat!”

As a producer and head of Marilyn Monroe Productions, she had acquired from playwright Terence Rattigan the English play. As a producer it had been up to her to get the proper leading man and, in as much as Olivier was a great actor who had played the part on the London stage, and also had box-office appeal, he’d been tagged for the part.

“Who the heck is ‘The Sleeping Prince,’ anyway?”

“It’s England, 1912,” Marilyn answered. “I’m an American chorus girl. I meet this Regent. He’s Acting Regent for his brother. He’s older, and he’s moneyed, and he’s sleeping—evidently sleeping. I wake him up”

“Had you met Olivier before your and his press conference a few weeks ago?”

“Years ago. Before I was anybody. That was really years ago. Gosh! They wouldn’t remember.”

She got that far-away look in her eyes people get when thinking back across the years.

“I met them through Johnny Hyde,” Marilyn said. By “them” she meant Olivier and his wife Vivien Leigh. Hyde, who has since died, was her agent and very dear friend then.

“Will you be doing any singing or dancing?” I asked.

“Certainly! In ‘Bus Stop,’ I sing ‘Old Black Magic’ standing on a table in a bus station.”

“Have you ever sung ‘Old Black Magic’?”

“No, but I’ve heard Sammy Davis, Jr. sing it!”

Marilyn, considerably thinner now—around the waist but not around the bodice—heaved a sigh, which is a very pretty sight. With all her schedule of working and studying, she gets to be a tired girl at times, and this was one of the times. But she remained bouncy and vibrant, frequently hopping up to answer a phone, or to look up a line in a book, or just to show us a new dress and its wonderful lines.

“You scored quite a triumph in your holdout against the studio,” I suggested.

“What I have settled for is a compromise,” Marilyn answered.

“A compromise!” I exclaimed. “Aren’t you underestimating and understating it? Didn’t you win a big victory?”

Not that I had been completely taken in by the Hollywood stories of Marilyn making an $8,000,000 deal with Twentieth. Nor has Marilyn. She didn’t know where the $8,000,000 figure came from. She wishes she did!

“It could be a lot more than that—or a lot less,” she elaborated.

“It was a compromise on both sides,” Marilyn explained. “I do not have story approval, but I do have director approval. That’s important. I have certain directors I’ll work for and I have trust in them and will do about anything they say. I know they won’t let me do a bad story. Because, you know, you can have a wonderful story and a lousy director and hurt yourself.”

“What directors do you have great faith in?”

“Oh, of course Elia Kazan, John Huston, George Stevens and Billy Wilder. I love Huston for ‘Asphalt Jungle’ and Billy Wilder after ‘Seven Year Itch.’ ”

With a saucy toss of the Monroe head and torso, she said, “And I love George Stevens and Kazan even before I make a picture with them!”

Quite candidly then, Marilyn revealed for the first time her financial deal with Twentieth.

“I’m working for 20th Century-Fox for $100,000 a picture—the same $100,000 that—said I walked out on before!” she said.

The point was that she’d never actually received $100,000 a picture before this time.

That impression had erroneously been given. Now, however, she is to get that sum, thanks to her holdout.

“Do you have any participating interest in any of the pictures you’ll make with Twentieth?”

“No.”

“Then you can’t make more than $100,000 on any picture for Twentieth?”

“No—but I’ve got director approval!”

“What are you going to do with all your money?” I inquired.

“What money?” she laughed.

“A hundred thousand dollars a picture!”

“Well, when I get some money, I’d like to travel. To London, Paris, Rome, places like that . . . Russia.”

“Will you keep the New York apartment with the all-white bedroom?”

“Not permanently. Because it’s not really my apartment. It’s Milton’s and Amy’s. I plan to buy a house in New York.”

“Where?”

“Somewhere in the 60s . . . or 70s . . . or 80s . . . or somewhere.”

There’s been no change in Marilyn’s determination to live in New York most of the time, so that she may continue her studies under the great drama coach, Lee Strasberg, and also attend the Actors Studio, which Elia Kazan and Strasberg head.

“Did you hear about that actor who gave out a statement about you not being a member of Actors Studio?” I said.

“No! Who was it?”

For a moment I couldn’t remember.

“Was it a man or a woman?” she asked excitedly.

“A man.”

“Oh.”

Checking back, I found that actor William Smithers had said Marilyn only dropped in occasionally, that “it has become fashionable” to go to Actors Studio, and that Marilyn was one of the fashionable ones.

Swiftly, she ran over her busy New York study schedule in the months when she was “sitting out” her holdout.

Wednesdays and Fridays she had private classes with Strasberg—private in that they were not part of the Actors Studio. There was another Strasberg class, meeting Wednesdays and Thursdays.

“Tuesdays and Fridays I go to the Actors Studio. I’m not a member, but I’m one of the people privileged to observe.

“When you feel you’re ready to become a member of the class,” Marilyn breathed, “you do a scene, trying to make use of all the things you’ve learned. That is what I’m working toward. I will audition eventually—but there is plenty of time for that”

“How do you like the private classes?”

“They’re wonderful, but it seems to me that the other students are children, just children. I guess I’m really not a lot older than they are, but I feel like it. They’re nice kids—just wonderful.”

Marilyn looked positively bubbly with health when I saw her and she wished me to point out that the laryngitis and virus she had while in New York during the winter had been nothing serious at all. As a girl known for her robust good health, she didn’t want anybody to get the idea that she was beginning to be ill a lot.

“Of course, I could hardly talk for a while. I could only croak and whisper, but it was nothing serious,” she said.

During this time, she’d gotten a penicillin shot, although she’s supposedly allergic to penicillin.

“Where did you get the shot—in the usual place?” I asked.

“Sure—where else?” giggled Marilyn.

“And what was the name of the lucky doctor?”

Marilyn laughed again. Anyway, she had licked the virus finally and was back in action. This meant being called on day after day for personal appearances at charities. If she refused, she was likely to be called a snob. If she accepted, they would probably take her picture, and then somebody would say she was always getting her picture in the papers. It was not such an easy life, but Marilyn, and Milton Greene, tried to steer a sensible course, doing what they considered right and proper.

Naturally, I got around to asking her about her love life.

“I haven’t any,” Marilyn insisted. “I wish I did!”

Then she launched into a little discussion of that. There had been talk about a romance with Pulitzer-Prize playwright Arthur Miller, who had divorced his wife after fifteen years of marriage. Most vehemently, Marilyn denied there was any romance with Miller, who was an old friend, nothwithstanding the gossip.

“You know,” she said to me, “there was the same talk about me and—”

She named a famous American, middle-aged and attractive, also wealthy and married.

“And as I told you before, I’ve never even met him!” she said.

Not once during this talk was Joe DiMaggio’s name mentioned by either of us. There was nothing around that hinted of Joe. The atmosphere was more scholarly and artistic, than athletic. The impression was of a girl who, despite her charmingly amusing little flippancies, is trying hard to become a very serious actress—that is, a sincere actress, even though frequently an “exotic” one.

I left Marilyn, feeling—as I always do when I visit her—that this is one of the great women of our age. I regretted to hear, though, that such a beautiful, healthy girl had no romance in her life. It’s a shame—when there are so many men who are so willing!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1956