The Fall

PART IV

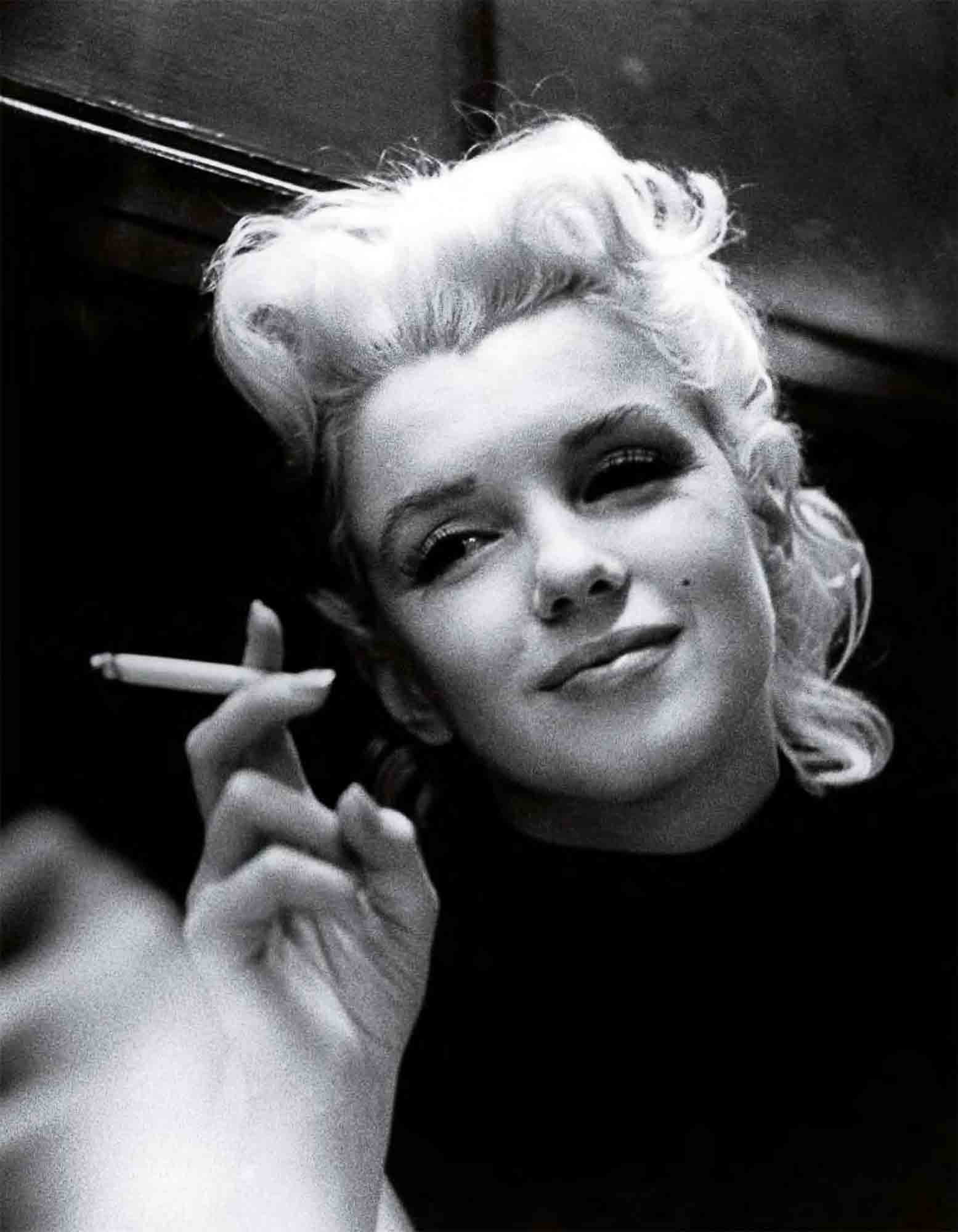

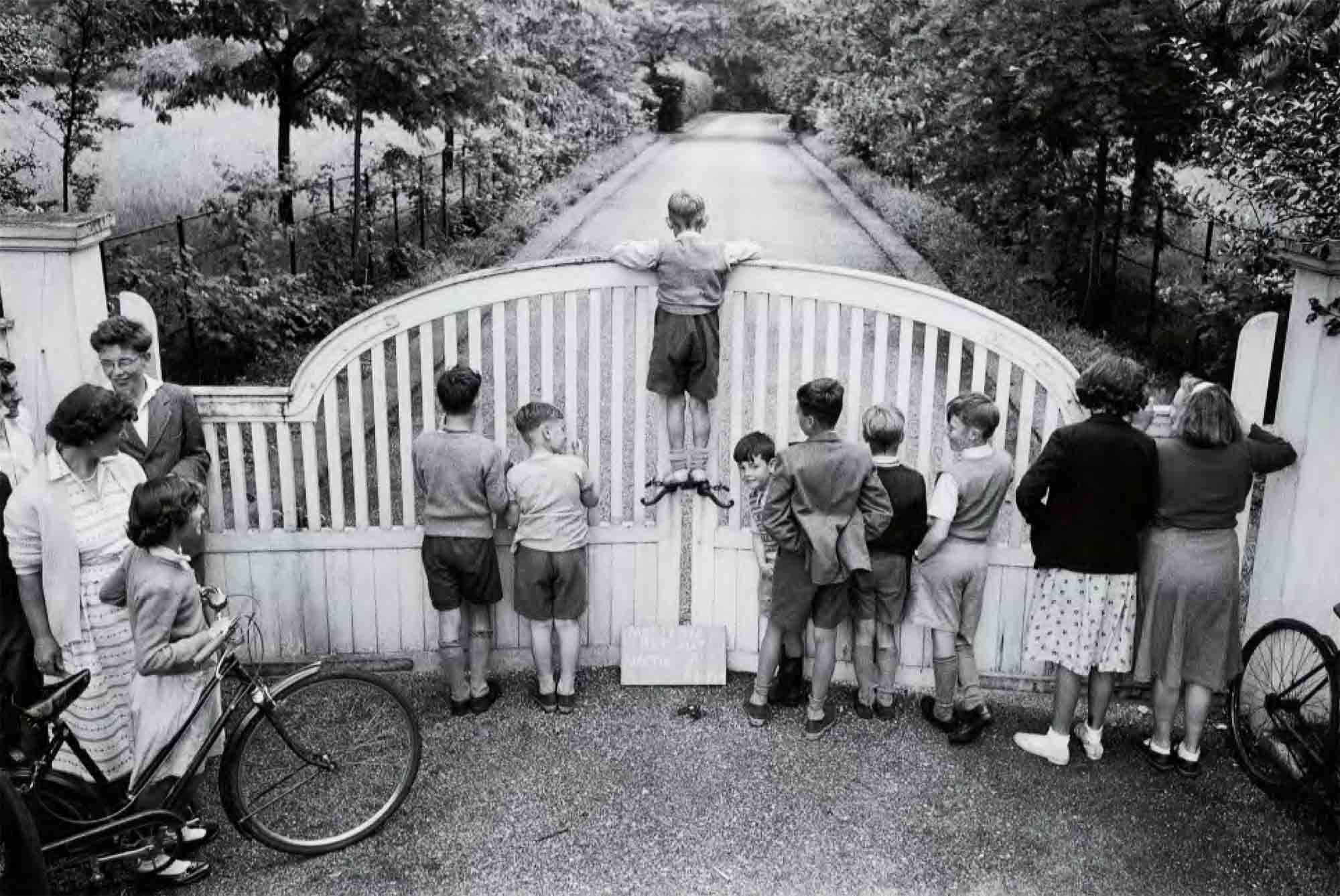

“A brilliant comedienne” was Laurence Olivier’s assessment of his costar Marilyn Monroe before they began filming The Prince and the Showgirl in London in 1956. “And therefore an extremely good actress,” he added. A few weeks into production, Olivier, who directed as well as acted in the movie, may have been somewhat less gracious with his words.

Not that Monroe showed any glaring lack of talent, but her behavior—and especially the conduct of her entourage—made for a tense, unhappy set. Beginning with Bus Stop, Monroe had replaced drama coach Natasha Lytess with Paula Strasberg, and the new tutor’s ubiquity would factor into all of Monroe’s final movies, much to the dismay of a string of directors. Olivier considered Strasberg a sycophant, a buttinsky and even a no-talent phony. There was also resentment that because Monroe was convinced her success hinged on the Method, Lee Strasberg had successfully demanded for his wife an astronomical pay increase to work on the film. So she was in the way, as Olivier saw it, and being royally rewarded for it.

Monroe, for her part, was plunging further into a dependence on pills for sleep and then, in turn, for alertness during the day. Various ailments caused weight fluctuations, which necessitated costume alterations. At one point, according to some accounts, Monroe suffered a miscarriage.

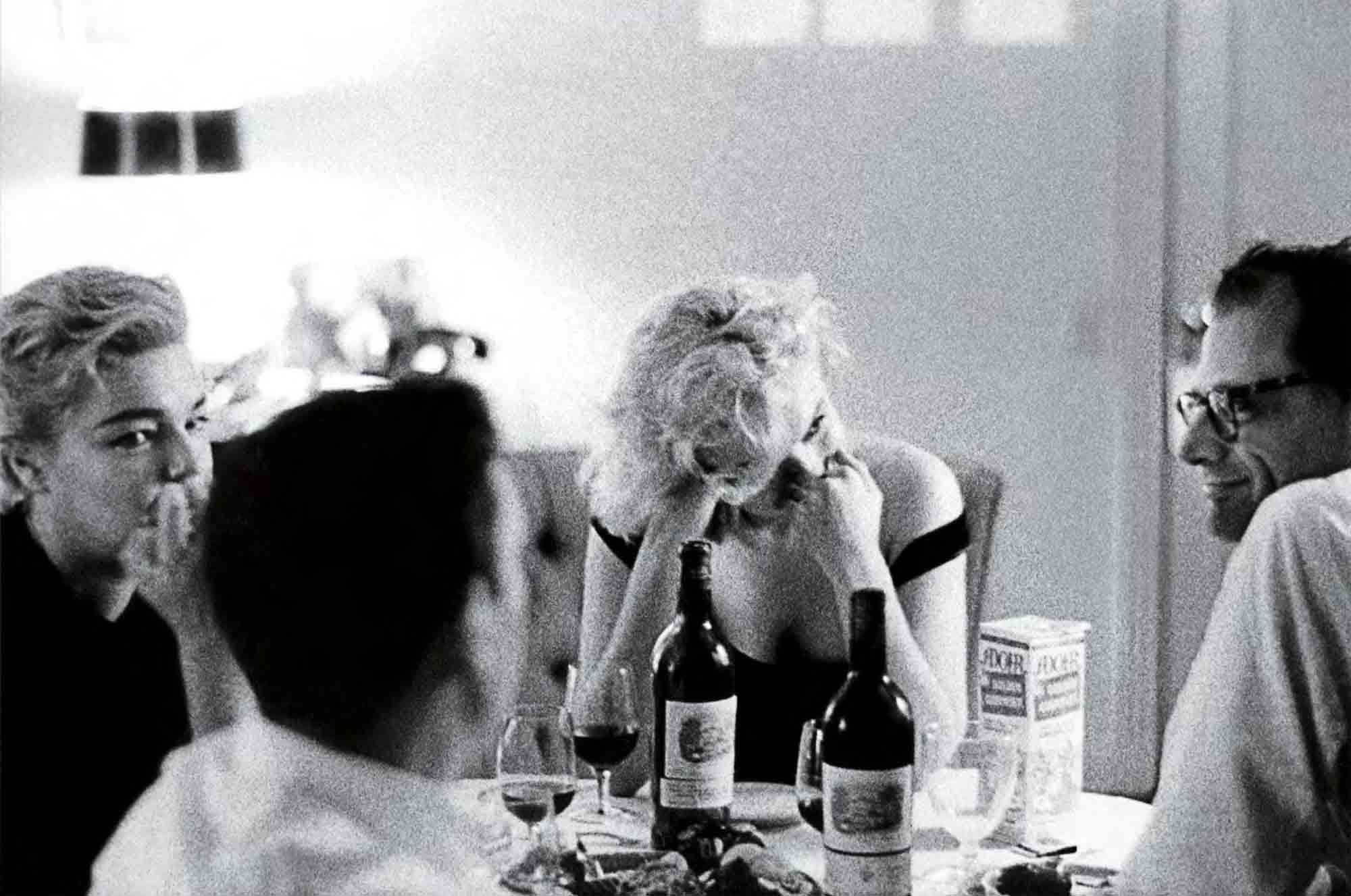

Which brings us to Arthur Miller. He was in London, too, and when visiting the set behaved, according to some who were there, in a highly arrogant manner. He seemed to display little respect for his wife.

Such observations were probably spot-on, for it seems the bloom went off the rose of this relationship as quickly as it had in Monroe’s earlier marriages. Monroe was understandably hurt when she happened upon an entry in the playwright’s open notebook that implied he was disappointed in her, that she wasn’t the “angel” he had initially thought her to be.

But amid all this rancor and recrimination, Monroe turned in a performance the gallant Larry Olivier called “quite wonderful.” In Italy, she won that country’s version of the Academy Award; in Britain, she was nominated for its equivalent; and in France, she won the Crystal Star. A corner was being turned in the way the film world regarded Marilyn Monroe, which is poignant to consider: Even as she was gaining what she had long sought, and what had looked to her as the ultimate redemption—as the making of her—she was getting caught in a downward spiral from which she would never escape.

After filming wrapped and Monroe returned to New York in late 1956, she started to cut some long-standing ties and forge new ones. She and longtime friend Milton Greene parted ways, and he was no longer vice president of her production company. Monroe also stopped seeing her (and Greene’s) psychoanalyst, switching to Dr. Marianne Kris, a close family friend of Sigmund Freud, whom she would visit five days a week. According to the biographies, there is little evidence that any of her decisions in this period led to greater emotional stability.

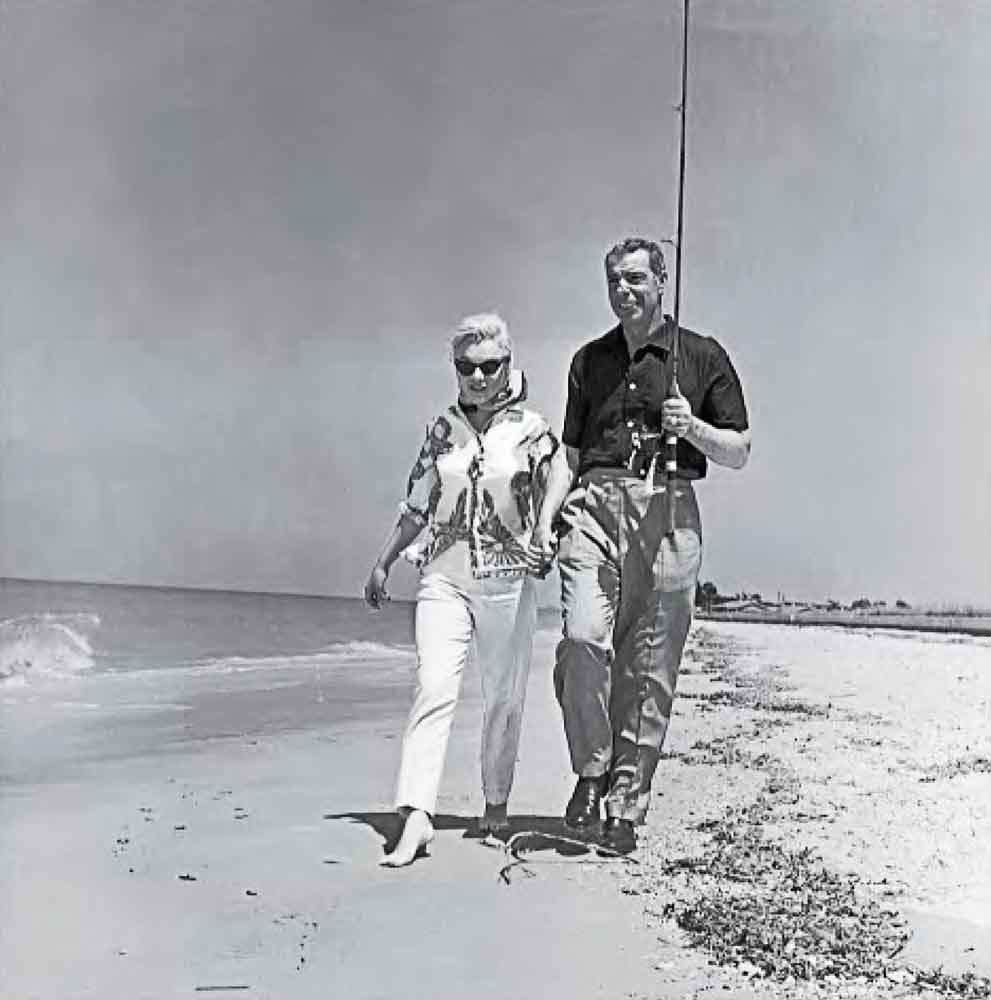

On the home front, Monroe hoped domesticity, time away from the movies and, most crucially, a baby might improve things. She and Miller spent the summer on Long Island, New York, where they tried to start a family. Monroe did conceive, but it turned out to be an ectopic pregnancy, in which the fertilized egg grows outside the uterus. Such a condition is serious and can lead to the death of the mother. The pregnancy was terminated soon after, in August 1957, and Monroe, who desperately wanted a child, was shattered. She was gaining weight, drinking too much and, according to some sources, taking copious amounts of sleeping pills. The pills would, reportedly, lead to a string of overdoses in the years to come. Biographer Barbara Learning says that not long after the pregnancy, Miller found his wife collapsed and breathing irregularly—a “sound [that] would become terrifyingly familiar” during the rest of their marriage.

Was there any refuge for Marilyn Monroe? No one could say, but in July 1958, with her husband’s encouragement, she returned to Hollywood, after agreeing to play the part of Sugar Kane Kowalczyk in director Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot. Her behavior on that production made what had transpired during The Prince and the Showgirl shoot look like a pleasant stroll through Kensington Gardens. She was routinely late, unsure of her lines and insistent on numerous retakes of the simplest scenes. The merest slipup could cause tears, which meant her makeup needed to be retouched. From a thermos, according to Learning, she sipped vermouth throughout the day.

“We were in mid-flight,” Wilder is quoted as saying in the Anthony Summers biography Goddess, “and there was a nut on the plane.” Wilder said elsewhere that instead of the Actors Studio, “she should have gone to a train-engineer’s school . . . to learn something about arriving on schedule.” He elaborated for biographer Donald Spoto: “To tell the truth, she was impossible—not just difficult . . . There were days I could have strangled her, but there were wonderful days, too, when we all knew she was brilliant . . . Yes, the final product was worth it, but at the time we were never convinced there would be a final product.”

That product, which is regarded as a comedy classic today, was a smash hit, garnering six Oscar nominations. Monroe won a Golden Globe for her performance.

If we did not now know what was going on behind the scenes, this could be regarded as a high point of her life.

Monroe became pregnant yet again in the autumn of 1958. Yet again she miscarried. Yet again she took some time off, then returned to the business of making movies.

In 1959 and ’60 she worked on Let’s Make Love, a fraught production floating on a leaky script that had been doctored, unsuccessfully, by Arthur Miller. On the set, Monroe’s conduct was what could now be characterized as “characteristic.” Off the set, she had an affair with her co-star, the French actor Yves Montand. While this can technically be seen as cheating on Miller, consider that even earlier, after meeting the playwright during the filming of Some Like It Hot, director Billy Wilder felt that “at last I met someone who resented her more than I did.” There was no longer any love lost between the husband and wife—no love lost and no love left.

Miller had been working for a few years on a screenplay that at first he had intended as a kind of homage—a love letter—to Monroe. She was never enthusiastic about the depressed divorcee role Miller had written for her; she found it hit wholly too close to home. But the playwright was dogged in his determination to get the film made. The movie was The Misfits, and it would be the last that Monroe would ever complete.

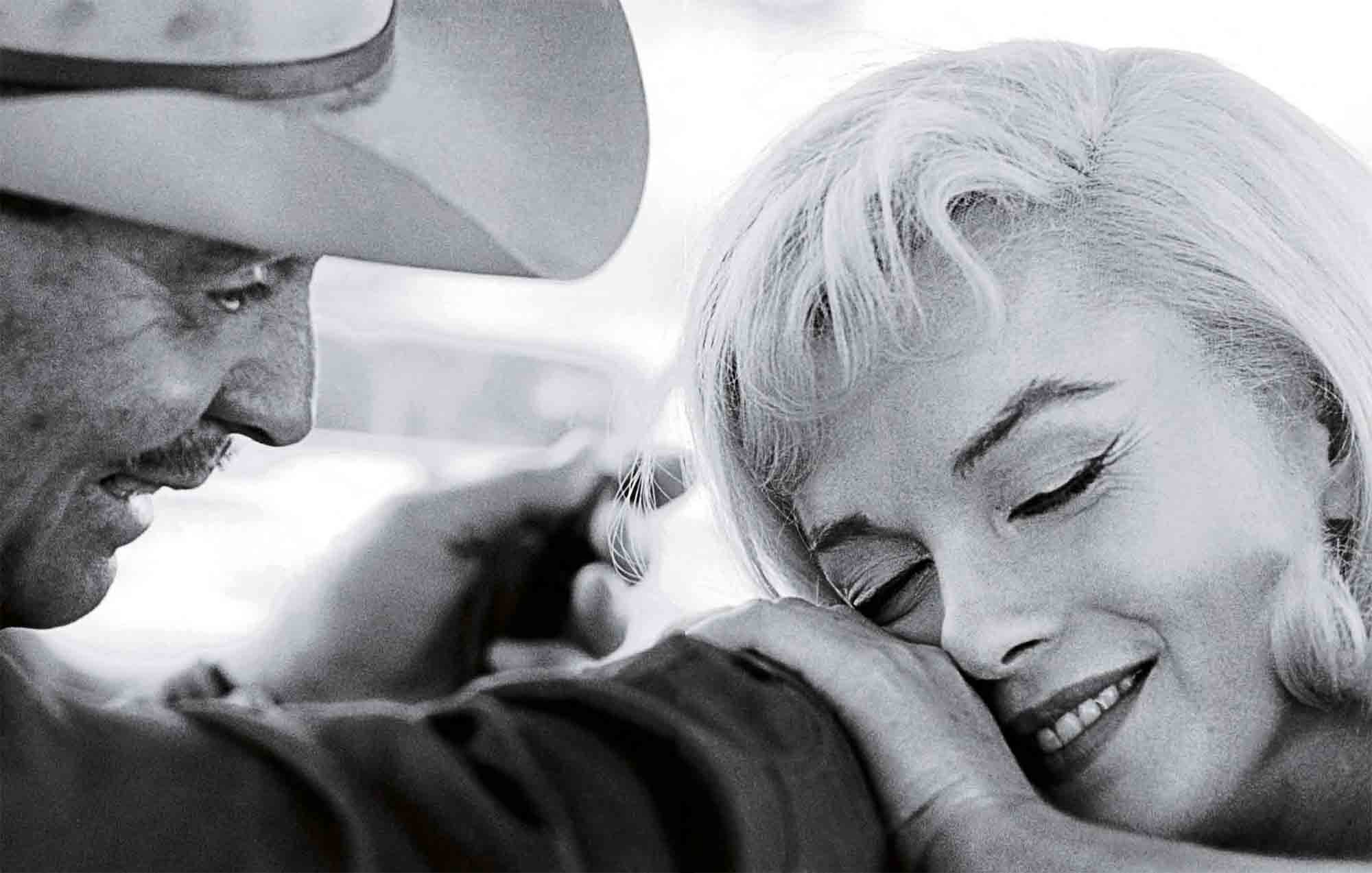

She was hardly alone in causing problems on this set. The heat in the Nevada desert, where the film was shot in the summer and fall of 1960, was oppressive and had everyone on edge. Miller was constantly revising his screenplay, which didn’t help matters, and constantly feuding with his wife. As for the director, John Huston, his penchant for drinking and all-night gambling left him so debilitated at times that he would fall asleep in the director’s chair.

But if blame for the generally miserable atmosphere can be spread around, certainly Monroe merits her share. Her consumption of addictive barbiturates, which she sometimes pricked with a pin to hasten their effect, was on the rise, and she may have been taking other drugs as well. The medications can and apparently did cause depression, confusion and slurred speech. She was mighty difficult to awaken for work—some mornings, she was taken bodily to the shower and then her makeup artist would apply cosmetics while she lay in bed. The phrase absolute mess pretty well describes her condition. Her costar Clark Gable tried to support her, but it was an impossible task. At one point, Huston shut down the set for a week while Monroe was sent to a hospital to dry out and regain strength. (At least one of Monroe’s biographers, Donald Spoto, asserts that Huston orchestrated the hospitalization so that he could take several days off to deal with his gambling debts.) Monroe returned to the set and, against all odds, finished the film. Gable reportedly said after the sets had been struck, “Christ, I’m glad this picture’s finished.

She damn near gave me a heart attack.”

In early November, shortly after leaving Nevada, Monroe and Miller announced they were divorcing. Barely a week later, Gable died of a coronary at 59; there was speculation that the stresses of making The Misfits were a contributing factor. Monroe’s depression was only made worse now by an overwhelming sense of guilt.

If Monroe even registered the critical praise accorded her and Gable’s performances when The Misfits was released in January 1961, there was nothing that could improve her mental state. Her psychoanalyst, Dr. Kris, by some accounts, worried that she was becoming suicidal and urged hospitalization. One Sunday in early February, Monroe checked herself into the Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic in New York City. Once inside, she panicked. Was the madness that had consumed her mother being visited upon her? She slammed a chair into some glass, breaking off a piece. When personnel returned to her room, she threatened to cut herself with it if they didn’t let her go. “If you are going to treat me like a nut, I’ll act Like a nut,” she told them. She was taken by force to another room where, she Later wrote, the watts bore “the violence and markings” of previous patients. She heard the screams of other women. “I’m Locked up with these poor nutty people,” she wrote to Lee and Paula Strasberg in a plea for help. “I’m sure to end up a nut if I stay in this nightmare.”

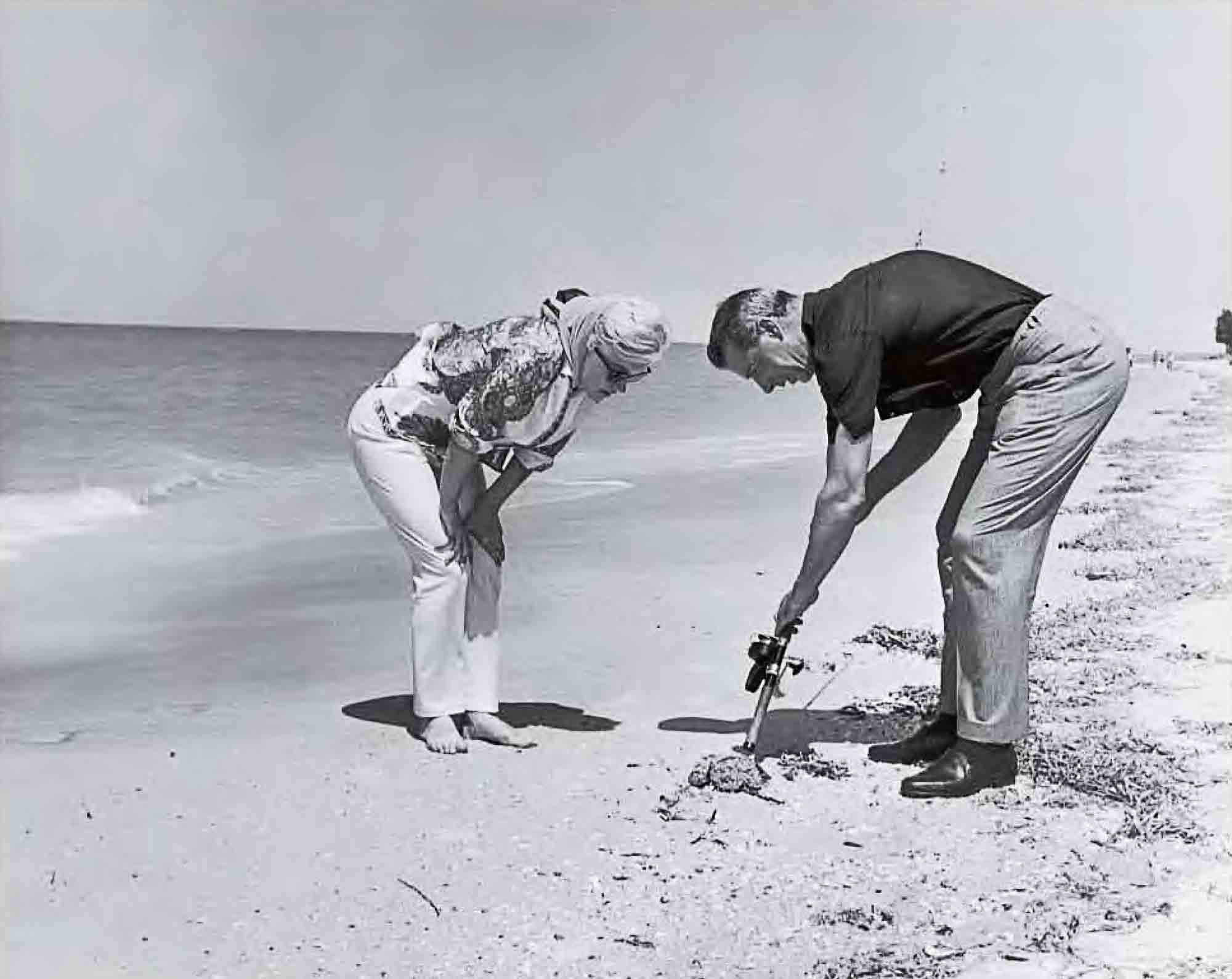

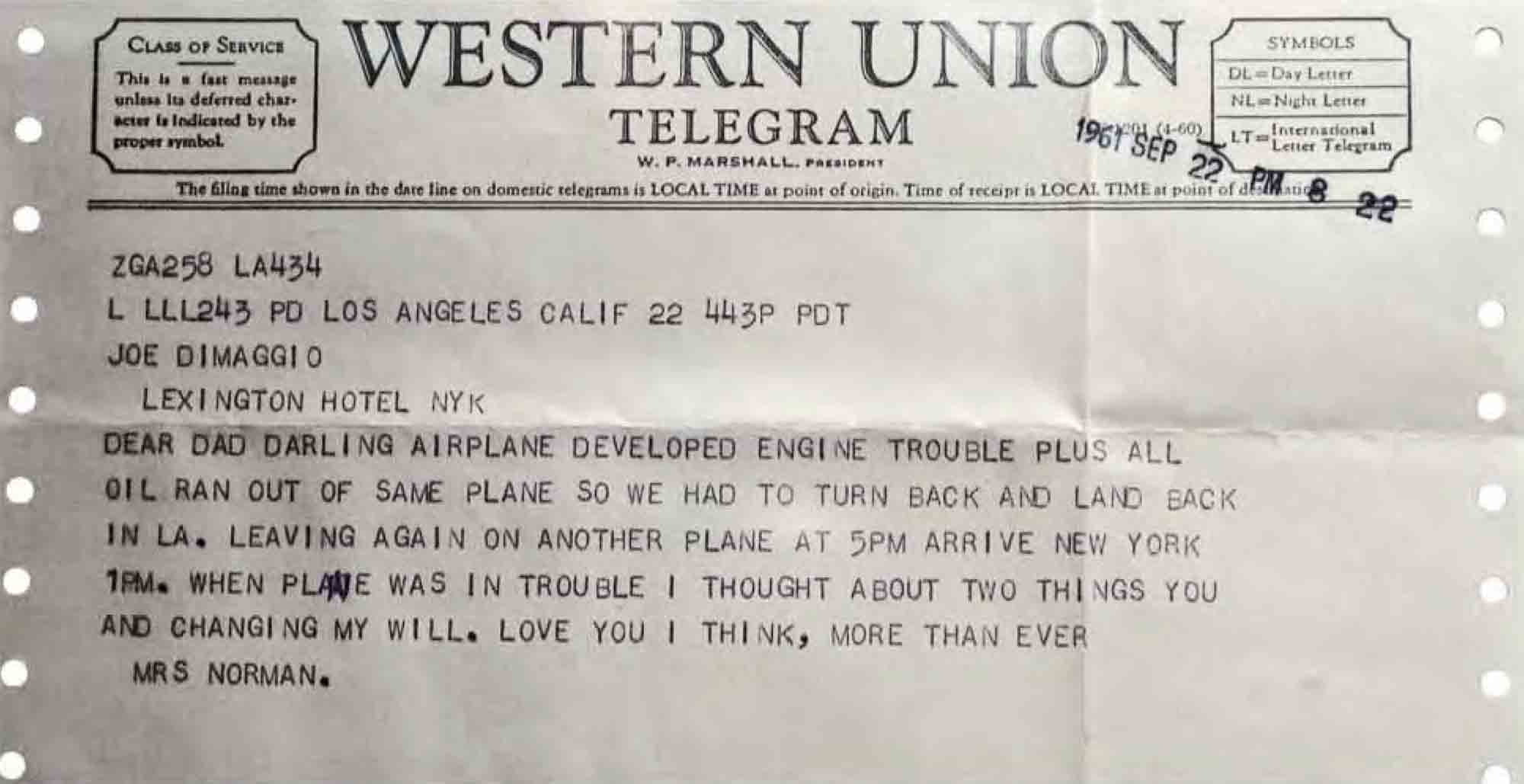

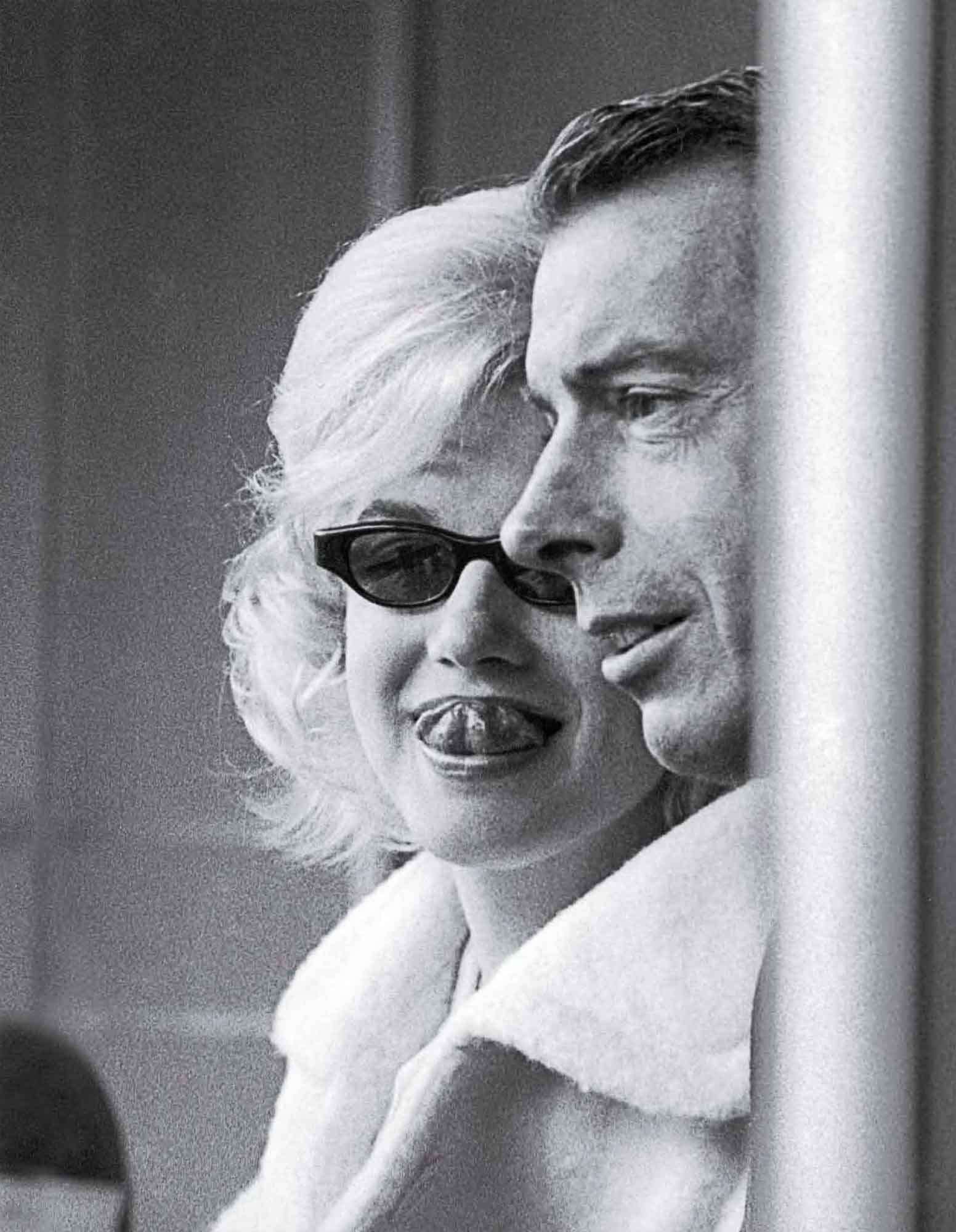

Three or four days after checking in (accounts differ), she reached Joe DiMaggio by phone in Florida. He rushed to New York and threatened Dr. Kris that he would tear apart the hospital “brick by brick” if Monroe was not released the next day. She was, and DiMaggio would stay in the picture from here on out. (Some biographers maintain that there was talk of a remarriage, and even plans for one, Late in Monroe’s Life.)

Monroe spent three weeks recuperating at Columbia University Medical Center, then moved back to Los Angeles, where she would make daily visits to Dr. Ralph Greenson, a psychiatrist whom she had originally seen in 1960.

This stage of Monroe’s Life, as chronicled in dozens of biographies, each with its own point of view, becomes as hazy as it must have seemed to her white she Lived it. What really happened between the last weeks of 1961 and August 4,1962, depends entirety on which version a reader chooses to believe. Much of the murk involves the Kennedys and the extent of Monroe’s relationship with them. According to some retellings, in October 1961, Monroe met Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and the following month his brother President John F. Kennedy at separate parties hosted by their sister Pat and her husband, actor Peter Lawford. These would not be her last encounters with either brother, and it is a consensus view among her biographers that there was an affair between the actress and the President. Whether it went beyond a single night (one friend asserts that Monroe herself acknowledged a sexual liaison with JFK during a stay at Bing Crosby’s house in March 1962) and whether there was also an affair with Bobby Kennedy is still debated—as is the theory that the Kennedys had something to do with her death.

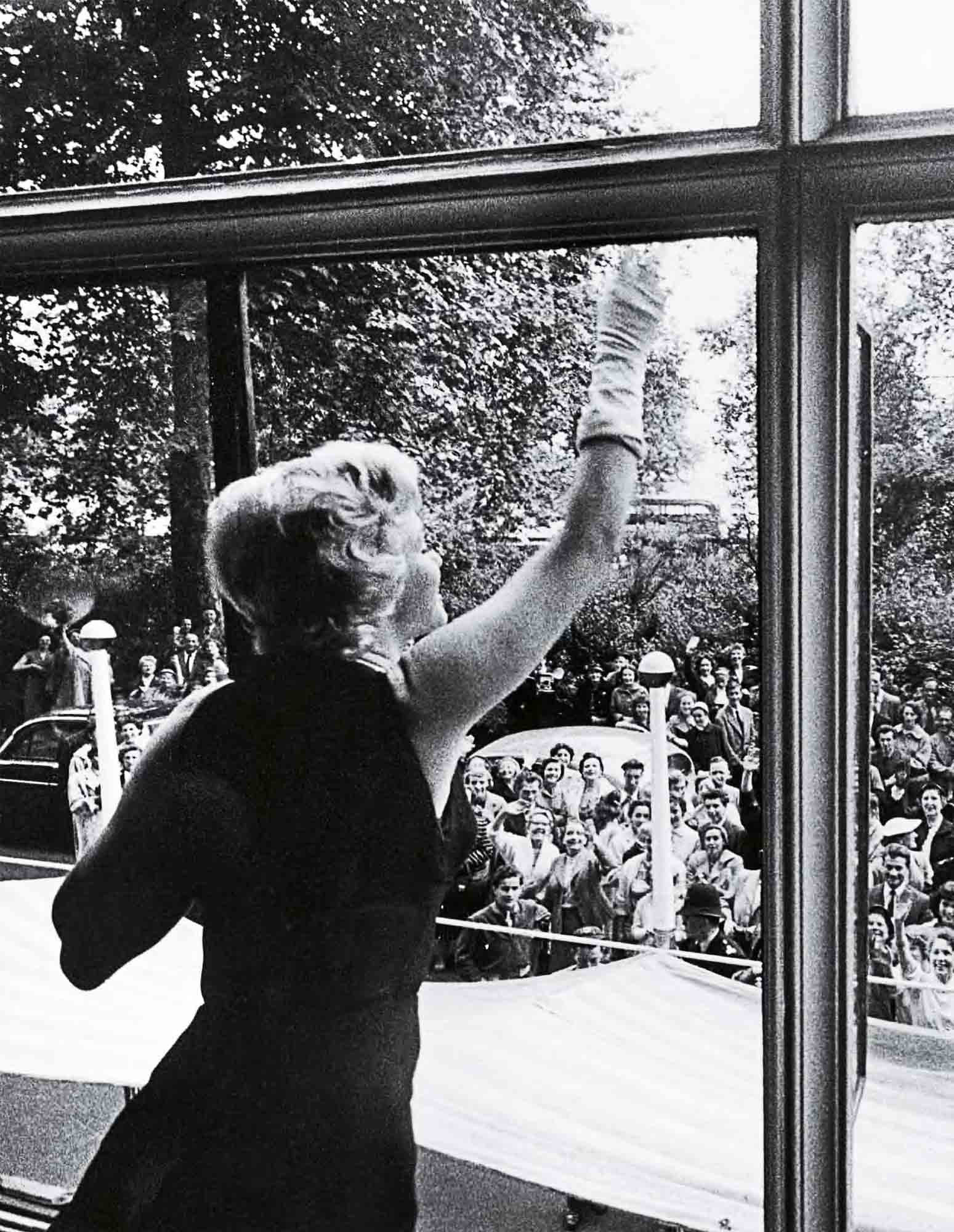

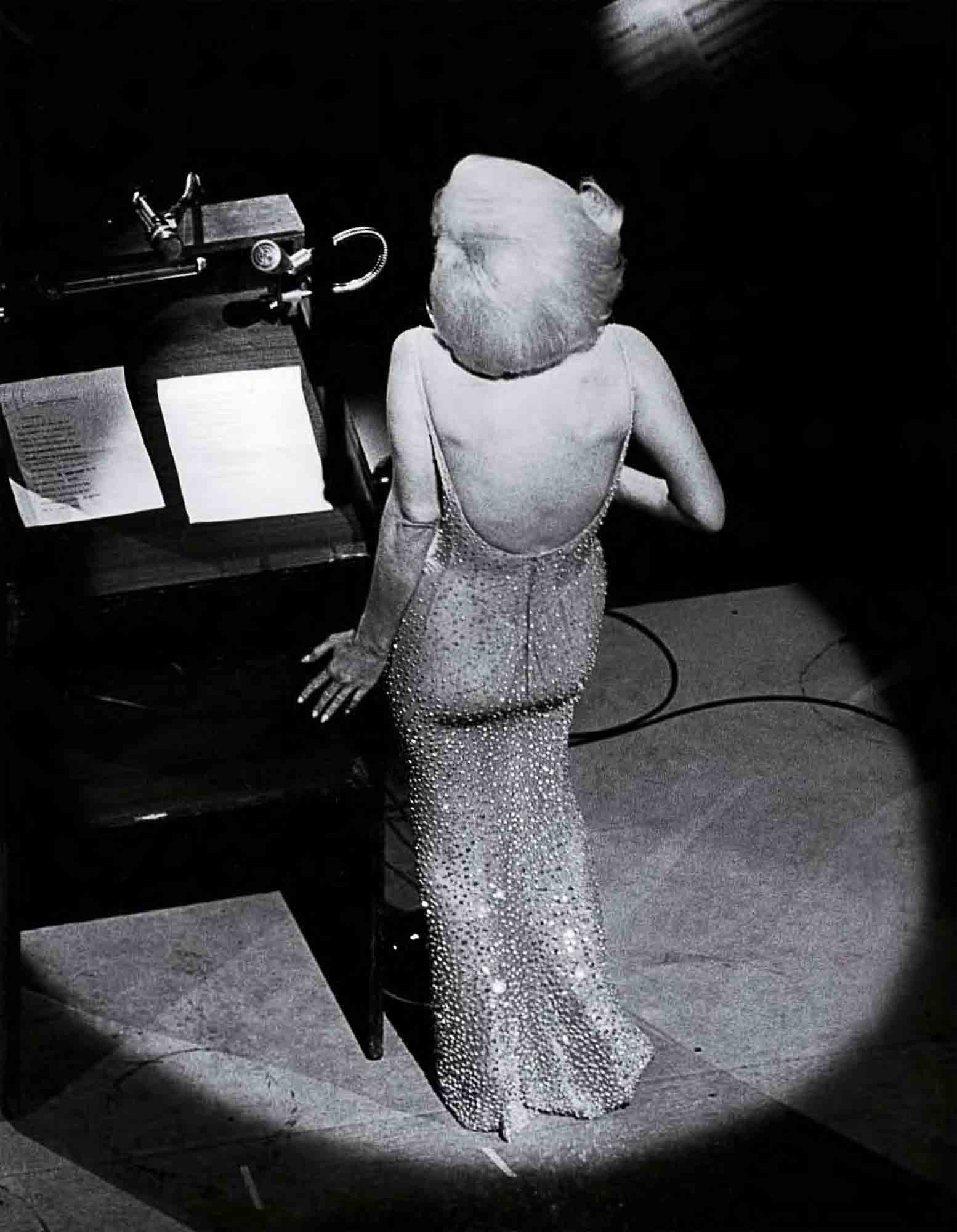

Monroe had signed to star in another film for Fox, Something’s Got to Give, but in April 1962, when time came to shoot her first scene, she was too ill to report for work. She stayed out for nearly three weeks, put in a few days of work, then said she was jetting to New York to take part in a Democratic fundraiser celebrating President Kennedy’s 65th birthday. The studio, despite having earlier approved the trip, countered that if she left, she would be in breach of contract. She ignored her bosses and on May 19 was introduced by Peter Lawford to 15,000 party-goers at Madison Square Garden. Shimmering like a disco ball in a dress as snug as plastic wrap, she proceeded to croon her best wishes to Kennedy in a voice somewhere between sultry and downright dirty. The President later told the crowd, “I can now retire from politics after having had ‘Happy Birthday’ sung to me in such a sweet, wholesome way.”

Two weeks later, back in California, Monroe celebrated her own 36th birthday on the film set with a sparkler-studded cake; it would be her last day at work. When she didn’t show up the following week, she was fired. The studio subsequently filed a $750,000 breach-of-contract lawsuit. Dean Martin, Monroe’s costar on Something’s Got to Give, said he would walk if Monroe wasn’t brought back. Fox capitulated, and by the beginning of August, the studio signed Monroe to a second contract.

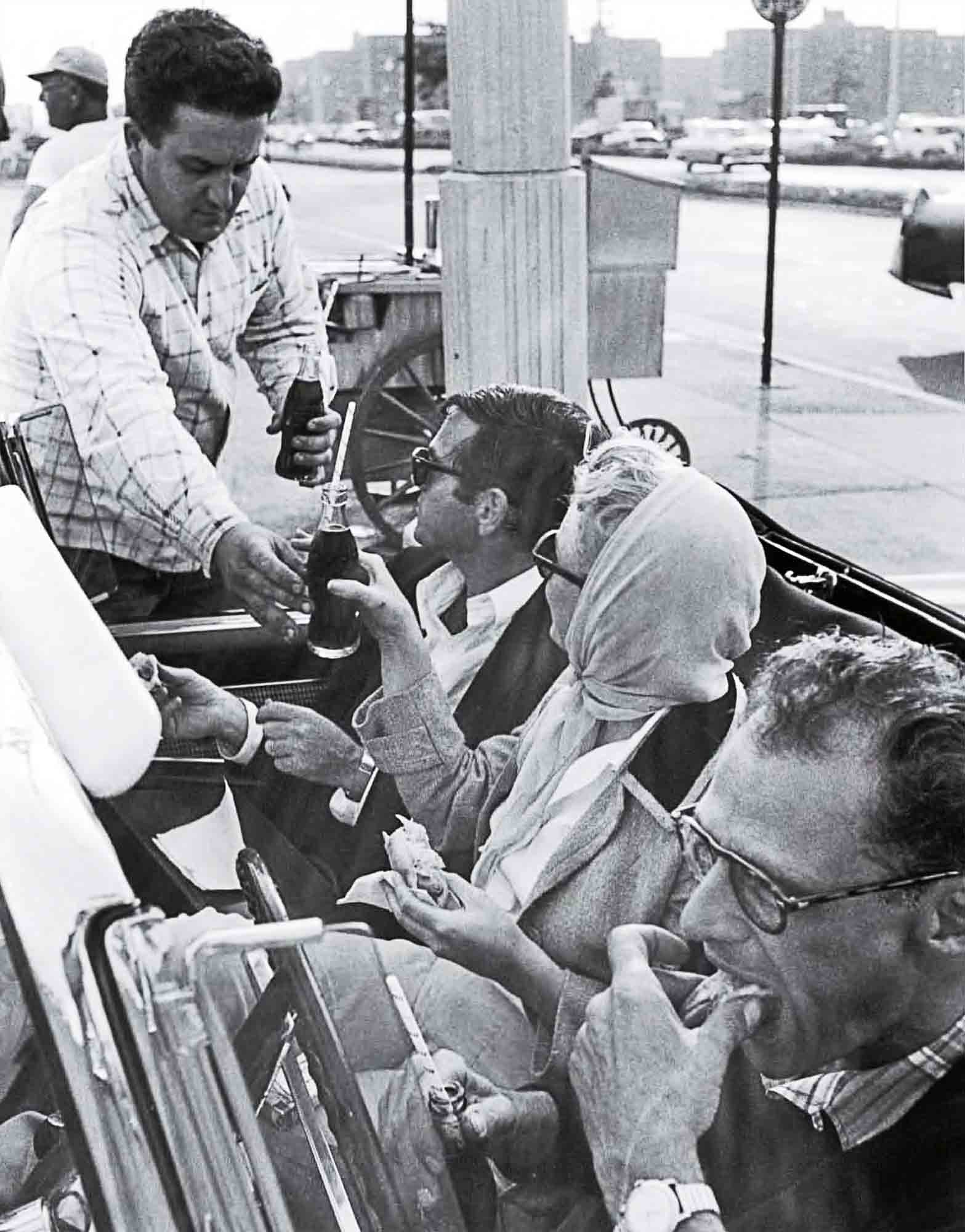

While she was negotiating this new deal, in July, Monroe met with LIFE’S Richard Meryman for a series of interviews that would prove to be her last. At one point, she compared fame to caviar—“not really for a daily diet, that’s not what fulfills you”—and said that celebrity could be a dangerous business: “You’re always running into people’s unconscious.” She talked about being “picked on” and pulled apart, treated like a commodity. She vented her anger at the studio.

“Fame will go by and, so long, I’ve had you, fame,” she said. “If it goes by, I’ve always known it was fickle. So at least it’s something I experienced, but that’s not where I live.”

She said further: “I don’t think people will turn against me, at least not by themselves. I like people. The ‘public’ scares me, but people I trust.”

She added, again referring to the idea of fame: “It might be kind of a relief to be finished.”

Meryman, upon seeing Monroe so agitated, asked if many friends had called to offer support. She paused and, looking hurt, answered softly, “No.”

At the end of their interview, she implored Meryman sadly, “Please don’t make me look like a joke!”

Biographical reports of Monroe’s last weeks differ wildly. In one, she is a woman on the mend and in good spirits; in another, she’s wresting control of her life from Dr. Greenson, with whom she had become disillusioned; in the next, she is addled by drugs and despair, careering toward her doom. Which was it? We’ll never know for certain.

Of August 4, 1962, which she spent at her home in Brentwood, only a few details are generally accepted: We know that Monroe spent part of the day meeting with a photographer to approve for publication nude poses he had taken on the set of Something’s Got to Give. She met with Dr. Greenson sometime in the afternoon and into the evening. Before 8 p.m., she took a phone call from her former stepson, Joe DiMaggio Jr. Shortly after, some accounts say, she was on the phone again, this time with Peter Lawford, who that night was having a small gathering to which she was invited. During their call, Lawford told police much later (his story undergoing revisions through the years), Monroe refused to join him. He said she was speaking in a slurred voice that became less and less audible. He yelled into the phone, trying to startle her, to no avail.

“Say goodbye to Pat,” she said, according to Lawford. “Say goodbye to Jack. And say goodbye to yourself because you’re a nice guy.”

At some point during the night, Monroe’s housekeeper, Eunice Murray, catted psychiatrist Greenson to say she suspected something was wrong. Greenson rushed to the scene, broke into the room and catted Monroe’s internist, Hyman Engelberg. Engelberg arrived, inspected the body and catted the police at 4:25 a.m.

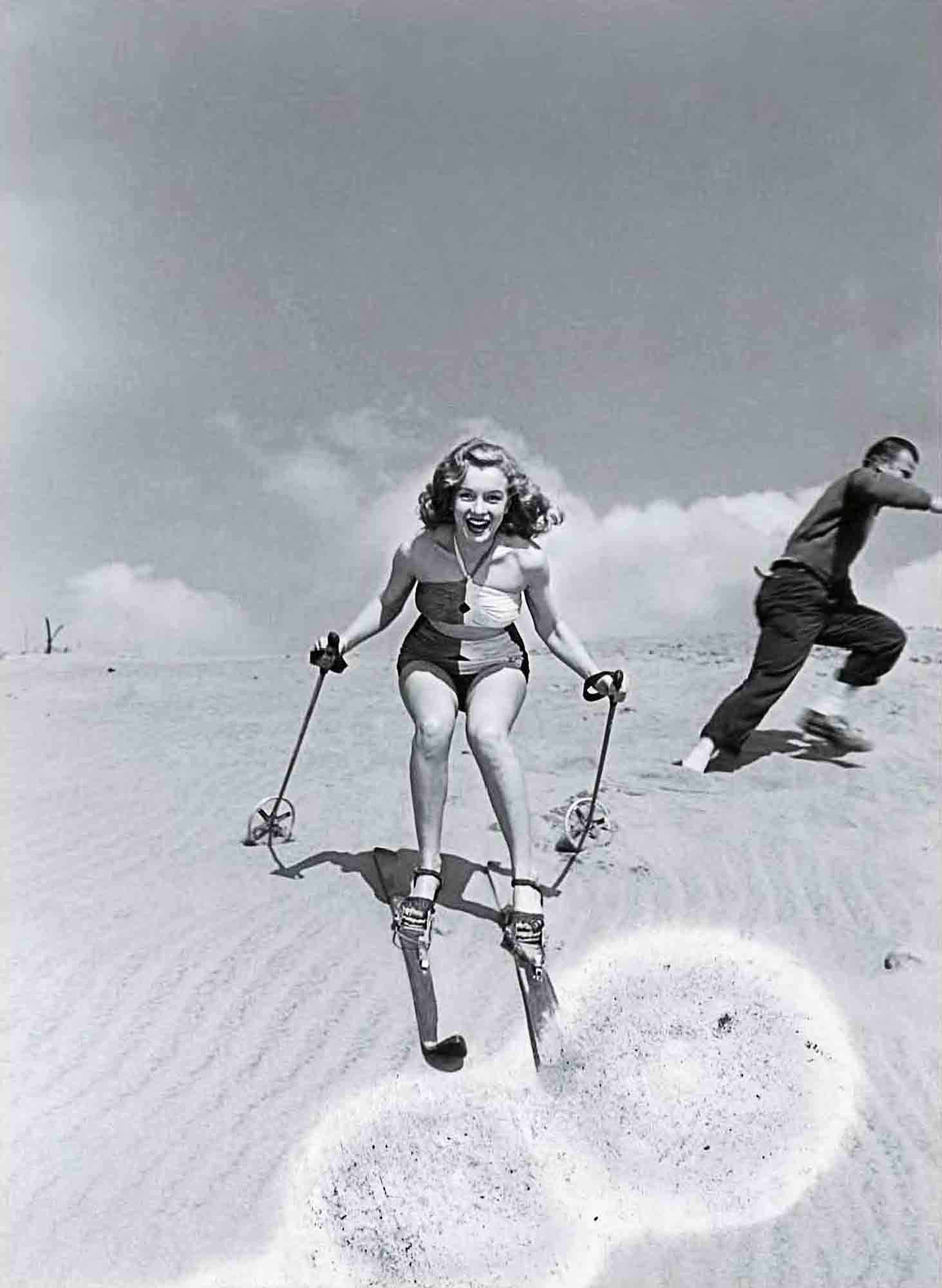

For a time, Marilyn Monroe was the most beautiful, most desired woman anywhere. But behind the glamorous images was a vulnerable star with an unhappy past. The story of Norma Jeane Baker’s unlikely path from foster homes to international fame to mysterious death is as dramatic as any film she ever made.

A small cache of pill bottles, one empty, sat on a night table beside the bed where Monroe fay dead when police arrived. No suicide note was found (some accounts hold that there was a note of some kind and Lawford destroyed it). Tests conducted during the autopsy revealed the barbiturate pentobarbital and the sedative chloral hydrate in her blood and more pentobarbital in her fiver. (Both drugs are used to treat insomnia.) The cause of death was ruled a drug overdose and probable suicide.

Circumstances, however, were muddied from the first by conflicting versions of the time fine, the possibility of tampering at the scene and questions about the completeness of the investigations by the police and the medical examiner.

When was Monroe’s body actually discovered? Why was there a fag—perhaps of several hours—between that discovery and when the police were catted? Why did the coroner receive results for only some of the fab tests? Was Bobby Kennedy in Los Angeles, as some have said, and did he visit Monroe? Might this have been a politically motivated murder done either by or on the behalf of the Kennedys—to protect reputations or state secrets? Alternately, was Monroe killed by an enemy of the Kennedys? Or was it, after all, just an accident?

“In all this discussion of the details of her dying,” Norman Mailer wrote in his impressionistic 1973 book, Marilyn, “we have lost the pain of her death. Marilyn is gone.”

It is a quote. LIFE MAGAZINE JULY 2017

Getler

11 Ağustos 2023A round of applause for your blog post.Much thanks again. Awesome.