The Story Of Shelley Winters’s Baby

The baby was not due until April of this year, but in her heart Shelley Winters hoped the child might come late, for then Vittorio would be back from Italy.

As she pictured the scene in her mind, he would drive her to the Cedars of Lebanon Hospital when her time came. Dr. Emil Krahulik, the eminent obstetrician, would be waiting. She would look at her husband, and Vittorio would give her one last kiss before they wheeled her into the delivery room.

For hours he would nervously pace the corridors, hoping for a boy, waiting for some word. Presently, they would come out and tell him that Shelley had given birth to a child. They would call him in to identify the infant as his, to count all the toes and fingers, to give his okay that everything was in order. Then when they wheeled her out to her room, Vittorio would hold her hand. They would gently lift her onto her bed. Vittorio would be permitted to remain at her side for only ten minutes. Soon the sedative would take effect, and she would pass to peaceful slumber.

That’s how Shelley Winters imagined the event.

What actually happened was entirely different. The birth of her little daughter was six weeks premature. The child’s father was 6,000 miles away. For a time it was touch and go as to whether the infant might live or die. Shelley herself was in danger.

The birth of her first child was as wild, chaotic, and unpredictable as Shelley Winters herself.

It started on the night of February 12th, a Thursday. Shelley was at home with her mother, Mrs. Rose Shrift. Shelley’s mother has been watching over her ever since Vittorio flew back to Italy last winter to stage Hamletwith his own company.

Toward eleven o’clock, Shelley who had the most miserable pregnancy known to woman, seven and a half months of uninterrupted illness, suddenly began calling, “Mama, mama!”

Mrs. Shrift rushed to her side.

“You’d better call Dr. Krahulik, Mama.”

The sac containing the amniotic fluid had broken. Shelley, like any young girl, was frightened and afraid. Her mother packed a bag. The doctor was called, and Shelley, white as a sheet, was raced down to the hospital. She was admitted at five minutes past midnight on Friday, the 13th. Taken to her room in the maternity section of the hospital, she was examined to see if there was any possibility of delaying the birth. In first births there are occasional false alarms which later subside.

This wasn’t true in Shelley’s case. The examination revealed that she would deliver her child within 36 hours at the latest.

Vittorio was notified in Rome, and although he’s been a father once before—he has another daughter, seven-year-old Paula, by a previous marriage—he got so excited that he made little sense on the transatlantic phone. Within the next 12 hours he called twice to find out how Shelley was. “Has the baby come yet?” he shouted. Shelley’s mother told him, “No.”

It was after midnight, in the early morning of the 14th that Shelley was wheeled into the delivery room. At 2:47 A.M., a tiny, dark-haired female baby was taken from her. The girl weighed four pounds, ten ounces, the premature birth undoubtedly being caused by Shelley’s profound anemia.

During the course of her pregnancy, Shelley had suddenly grown anemic, and on several occasions, in addition to vitamins, hormones, and injections of iron, she’d been given blood transfusions. What caused her anemia is difficult to tell. Early in her pregnancy she visited Vittorio when he was in Mexico making Sombrero,and it is suspected that she caught some bacteria south of the border which weakened her whole system.

As soon as the baby was born, little Vittoria was placed into an Armstrong incubator, and the mother told that the child was doing fine.

The truth, however, was that the infant wasn’t breathing properly. Something was wrong with baby Gassmann’s respiratory system—she couldn’t seem to get enough air down her lungs. The little girl who was later named Vittoria Gina Gassmann hovered between life and death.

Shelley’s pediatrician was called immediately, and he in turn, brought in Dr. Arthur Parmelee, one of the crack children’s specialists in the country, as a consultant. Dr. Parmelee examined the child, ordered special day and night nurses to see that the baby’s temperature never went lower than 97 degrees nor higher than 99 degrees.

If Vittoria Gina lived for the next 48 hours her chances of survival were excellent.

When Shelley awoke she asked for her baby and was told it was in the incubator. Her reaction was typical of all mothers who give birth to premature babies. Physically she felt exhausted and yet the maternal instinct in her cried out for some way in which to help her child. There was no way, nothing she could do, and a period of frustration seized her.

“It seemed like a year,” she says in retrospect, “before they let me see my baby.”

When presently she did, Shelley noticed that her baby’s skin seemed pale, almost blue. Shelley began to worry. The nurses told her that of three and a half million babies born in the United States each year, 1 out of 20, approximately five per cent, are premature. They told her not to worry; that her baby weighed almost five pounds; that Winston Churchill, Victor Hugo, and Sir Isaac Newton had all been born ahead of time.

But Shelley is a worrier, and for the first two days there was nothing anyone could say or do to alleviate her fears. She prayed for her baby’s survival.

Oddly enough, Shelley who loves publicity, cautioned everyone to say absolutely nothing about the birth of her child. “I was trying to regain my strength,” she says now. “I didn’t want to be bothered by reporters and press agents asking questions.”

As a result of this insistence upon secrecy, it wasn’t until three days after the baby was born that the item made the newspapers. By that time Shelley had been assured by the doctors that her infant had passed the crisis and, barring some unforseen relapse, would live.

In Rome, Vittorio said nothing for public consumption about his new daughter. He did, however, manage to give out with a professional announcement. He and his company, he stated, planned to go to the United States to tour the country in an Italian repertory program. The bill would include his four-hour-long production of Hamlet. He would bring with him such stars as Elena Zareschi and Anna Proclemer.

In Hollywood there has been a good deal of talk about Vittorio’s conduct during Shelley’s pregnancy. Other actresses have said that Vittorio, regardless of his commitments in Rome, should have stayed at Shelley’s side when she needed him most.

“I know,” a colleague of Shelley’s said, “that the Italian Government backed his Repertory Company. I know that he didn’t want to put a lot of people out of work. I know all about the show-must-go-on tradition, and I know how Italian men feel about childbirth. To their way of thinking, giving birth to a baby is no worse than having a bad cold. I realize all that, but let’s face facts.

“Vittorio today would be relatively unheard of in the United States. It was Shelley who brought him to Hollywood; Shelley who got him in touch with the right people; Shelley who helped him land that contract at Metro.

“I’m the first to admit that she may not be the sweetest or most well-bred girl in the world. She may not even be the most companionable wife. Maybe they argued like cats and dogs. But she did fly to Mexico to be with him. She did tell him she was pregnant.

“Under the circumstances I think he should have stayed in this country. Not that he could have helped Shelley have the baby, but it would’ve helped her morale. And when the baby did come, well—I think he should’ve been around to share the responsibility.

“After all the baby almost died. She had a mucous obstruction in her throat, and the doctors were afraid she was coming down with pneumonia—in which event she would certainly have died—and they had to keep her under oxygen and feed her by dropper. The baby’s all right now—I mean the doctors say she’s passed the danger zone, and Vittorio is the proud father. Only I’d like to ask one question. Where was he when the going was tough?”

In Rome when this question was put to Vittorio Gassmann he said, “Look, Shelley is a very sensible girl. She knew I had these commitments even before she came with child. If there was anything I could do that would have really helped, I would have tried to stay behind. But Shelley herself told me to go.

“We thought for a while that maybe she could come to Rome with me, but the doctors would not allow. it. When Shelley gave birth I spoke to her over the phone. She told me about our darling little daughter.

“I could not fly back to California just for the weekend. I’m opening in a new Italian play here. Late in April I will return to the United States. In the meantime, Shelley knows that I am thinking of her and our baby every minute.

“Believe me when I tell you that it is very hard for me to be patient. I know what Shelley went through. But there are certain times when husbands are helpless. And that is one of the times.

“Any stories that Shelley and I did not get along, they’re not true. I love Shelley more than I have ever loved her before, and if I did not have these stage commitments, I swear to you, I would be on the first plane back to California. I have spoken to Shelley several times now, and she tells me that she and our baby are fine. I thank God.”

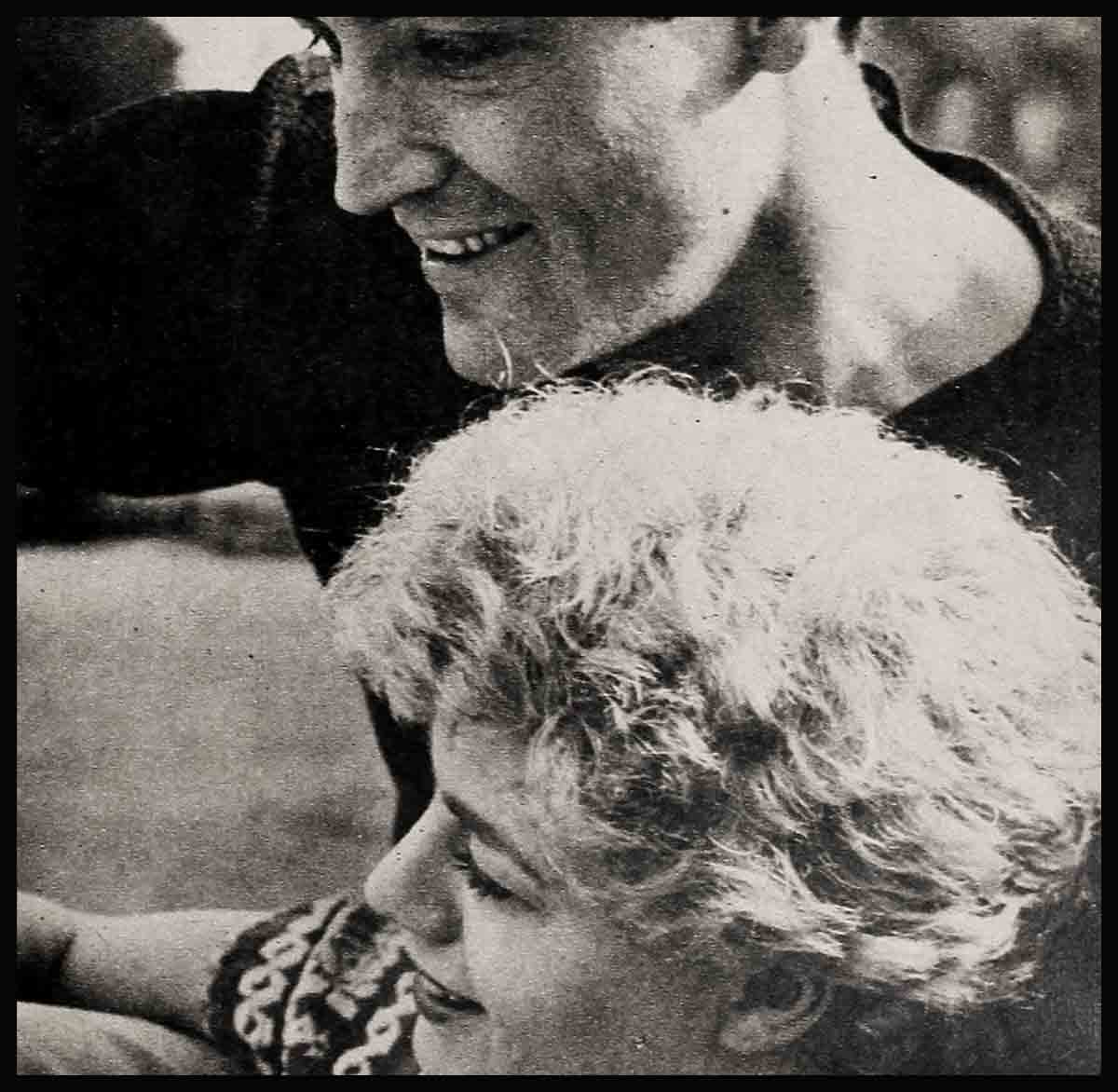

As for Shelley, back home with her firstborn, in the duplex apartment she bought last year, she is well on the road to complete recovery from her near-tragic experience.

Child-birth has also wrought several personality changes in her makeup. She seems no longer obsessed by her career. Constant chatter concerning productions and castings no longer occupy her tongue. Having performed the primary function of womanhood—the perpetuation of the life cycle—she seems strangely subdued like a soldier who has gone into battle and for one fast fleeting moment, met his Maker.

No one brushes by Death without some chastisement—not even the tempest-tossed new mother, Shelley Winters.

THE END

—BY ALICE HOFFMAN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1953

No Comments