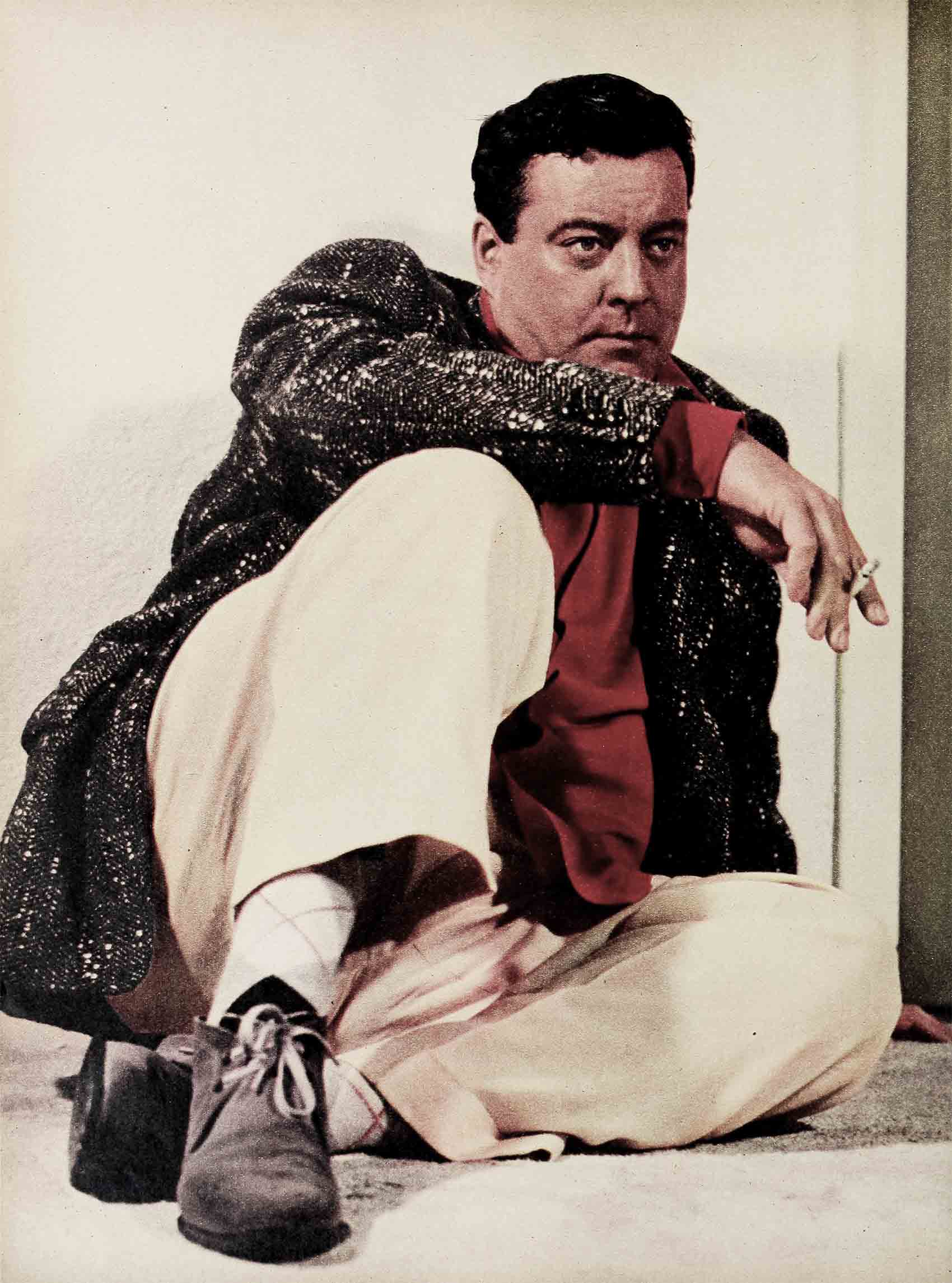

Jackie Gleason

Jackie Gleason should have the world by the tail. But he is one of its most miserable men.

There he is—all 285 or 265 or 245 pounds of him—and he looks fat (which he is) and sassy (which he can be). Not yet forty, he is one of America’s funniest and richest comedians. He could even lay off work tomorrow and be rich for the rest of his life. Working, he is worth millions. He can afford everything he wants—clothes by the custom-made carload, apartments, country homes, European trips—and have plenty left over to give his wife and daughters the 14¼ per cent of his income which the judge deemed fair at the time of his and Genevieve’s separation. Although he cannot get divorced and marry again, because he is an ardent Catholic, he is happily in love with Marilyn Taylor, the pretty young sister of his choreographer, June Taylor. And Marilyn, while perhaps not overjoyed that the wedding bells will never ring, loves him and does not protest.

Jackie looks happy. To watch him when he is off television, you’d think he didn’t have a qualm on any question. There he is, brandishing a glass and spouting off-color quips as fast as lightning. Or sitting around the $25,000-a-year duplex apartment that houses the Jackie Gleason Enterprises, Incorporated, and merely waving a hand to get service from an army of yes men that swarms all over—out in the kitchen, up in the little balcony, up in the bedrooms and rehearsal halls. Or, legs on a table, overseeing the expensive decorating job being done on his new, private apartment. Or running through his fast, one-day rehearsal being the big boss of a theatreful of observers, friends, hangers-on, actors and just plain fans who sneaked in. Or conducting script conferences at the head of the table up in his private office at the theatre, with everyone else relegated to sideline seats and guards keeping others out and away from The Great Gleason.

It’s a great life, you say? It is, and Jackie is honestly grateful for all his fortune and fame. It’s inside that he’s miserable.

The symptoms are there for anyone to see. The most obvious one is Jackie’s weight, which goes up and down like a barometer in a hurricane. It varies from a low of 185 up to 285 (where it was when he began his public dieting recently) and his closets have to be full of suits, jackets and slacks in all the many sizes he might need. A man who loves to eat—especially spaghetti and all. the highly spiced Italian foods—and who likes his liquor—even triple shots—poor Jackie has had to starve himself on and off for years or he’d have been an even bigger blimp. He has lived on Rye Krisp during his dieting periods, or on steaks, or on graham crackers, or on lettuce and carrots and “skinny pills.” He has retired to hospitals again and again and starved himself on doctors’ orders (although he nearly always sneaked out to Toots Shor’s and lived it up a little between intakes of carrots).

Anyone whose weight can rise so rapidly, and anyone whose weight can fluctuate so erratically, is a sick man.

Jackie is the first to admit it. He has beaten a path to scores of doctors trying to find a cure. He even tried a few psychiatrists. He himself has figured out part of what’s wrong with him. He says that anyone who puts on weight has something bothering him, and eating gives that person a feeling of well-being. “If a guy could go out and get loaded, that would help. But a guy in this business has too much to remember, too much to think about. He can’t get loaded. So I eat.” What Jackie can’t figure out is what is bothering him. So, when he isn’t stuffing himself and even when he is—he tries to forget his unhappiness by keeping frantically busy.

Gleason never sleeps more than four hours a night. The rest of the time he is active, constantly—as though he were running away from himself. He insists on watching every line in his script. He checks the music, the camera angles, the costumes, the dance routines, everyone on his show. He collects books on hypnotism and mental telepathy—on all things occult (another sign that he is searching) and reads them, ferociously, three and four at one sitting. Although he cannot read or write music, he hums a tune and orders an orchestration of it. He records music albums, picking out all the numbers he himself doesn’t compose and waving a baton in front of the orchestra. He hands a room in his duplex over to a writer because he wants to put his biography on the stands. He tries to write novels, and, failing, tries to hire people to write out his plots for him. Not satisfied with just being a top banana, he wants to act seriously—and does, memorizing those scripts just as fast as he does his own. He keeps getting ideas for television shows and works on the production of the pilot films. He wants to make movies. He wants his Enterprises to branch out and go into non-show business lines like frozen foods. Jackie is never still. He probably keeps turning even during those four hours of sleep.

This frenetic activity has always been characteristic of Milton Berle’s “three favorite comedians.” Back before he was a huge hit, back when he was hungry and out of work, Jackie couldn’t keep still. When he wasn’t performing, he’d go to a nightclub and heckle whoever was. Or he’d stay up all night making merry and annoying the neighbors. One time, when he was an all-night disc jockey, he got bored with the routine of just playing records and talking between them, and threw a knock-down, drag-out party complete with refreshments and pretty girls. He got fired—as he knew he would—but he could not overcome the compulsion To Do Something. Even though his wife, whom he married very young, and his two girls needed the pay envelope from that job.

All this hustling and bustling is just part of the Gleason make-up. One other characteristic is his extravagance. Not just with money, but with words and gestures. He never sends anyone a dozen roses; he sends thirty-six and a little something extra. When he saw a vicuna coat he liked, he ordered a dozen of them—at some $300 per coat. When he diets, as we’ve noted, he does not cut down; he cuts out. When he hires an orchestra for his show, he has to have a big one. When he has dancers, he wants more than anyone else has. When he has a crowd scene on his show, he insists on a bigger crowd. As one observer put it, “He wants more people than Ivanhoe.” When he takes a country place for the summer, he decides that one is not enough and takes another—maybe a third, too. When he has an operation, he goes to Switzerland to have it. When he drinks, he never sips; when he eats, he never nibbles.

Jackie has always had this extravagant streak. He never hesitated to run up astronomical bills all over town, even in the days when his career was going nowhere fast. He didn’t used to borrow $5 or $10; he’d ask for $500. (He paid everyone back when he got in the chips.) When he was struggling along as a comic in small saloons, he didn’t pick a fight with a puny ringsider; he invited “Two-Ton” Tony Galento outside—and got his block knocked off.

Always dynamic, even back in Brooklyn as a kid, Jackie lost his wife’s love because of his excesses. Genevieve, from whom he had been separated many times before the final break came, just couldn’t take it. She accused Jackie of not being able to adjust to his success, and berated him for having a too-fabulous wardrobe, over-expensive jewelry, and too-elegant surroundings. Genevieve did not believe anyone should spend money with such reckless abandon—or so she said in her legal petition for more money. Jackie’s free-wheeling came as no surprise to her, however. Any man who borrows $500 and blows it in one nightclub outing is not going to turn into a miser when he gets in the chips. Just as any man who does not hesitate to ask a friend for a big hunk of money is not going to turn down his indigent pal when he is loaded.

Gleason is as generous as he is generously proportioned. He may not see his old boyhood friends all the time, but he remembers them with presents, he’s available for a touch, and he scatters their names all through his TV sketches. He is also followed by as large a retinue—which he supports—as any man in the business. His extravagance works both ways—things for himself and things for everyone he loves. And, looking at his face, which can break into the sweetest smile this side of an Ivory Soap ad, you know that here is a sweet man as well as a generous one.

He is just too flamboyant to be consistent. “Nothing in moderation” is the Gleason motto. When he gets mad at rehearsals, he does not draw the offender aside and whisper a light reprimand in his ear. Jackie yells at him in front of everyone. When he is frustrated by something or someone, he gets stomach aches, and will pull a tantrum at the drop of a “No” from a yes man.

All of this, as Gleason is the first to admit, is not normal. A man without self-discipline is a man without peace.

And Gleason craves peace. He doesn’t want to spend his twenty waking hours seven days a week in a rat race. That is why he is subject to fits of melancholy—despondency as deep as his hilarity is high.

He is envious of everyone who is at peace with the world. This is one reason he and Art Carney have that rapport that comes as a surprise to everyone who meets them for the first time. There is Art, a devoted and very happy family man who prefers being quiet, always polite, and never torn apart—and is always like that. And there is Jackie—noisy, sharp-spoken, and tormented. Art is too strong within himself to envy his boss, but he admires Gleason for his consummate skill as a comedian and for his generosity as a human being. Jackie, on the other hand, envies Art. He envies every man who is happy. And he is searching for something that can make him calm.

Why is Jackie always cataclysmic, never calm? For the answers to that, you have to go back to his childhood. It wasn’t easy for Jackie. His only, and older, brother died when he was three. His father did not come home one night when Jackie was eight, and has not been heard from since. To this day, Jackie does not know whether Mr. Gleason walked out on the family or met with foul play. Then his mother died when he was sixteen, leaving him alone in the world with thirty-six cents in his pocket. A childhood like that one is enough to ruin a man forever. What Jackie’s detractors should remember is that it is amazing he mustered any spunk at all after that series of family disasters.

But even as a boy, Jackie was full of spunk. When he wanted to move nearer a grammar-school flame, he packed all the family belongings into a junk wagon and wheeled them over to another apartment all by himself. (As he got older, he was one of the boys who hung around the corner drugstore and cracked wise remarks at all the passersby. That, too, takes spunk of a sort.) The day his mother was buried, he emceed a stage show in a movie house because it paid $4 and he needed the money. That takes real intestinal fortitude—and it is a gesture that leaves a scar.

Jackie’s religious upbringing, which left him with deep convictions, gives him what peace he has. In spite of years of batting around burlesque houses and nightclubs, he is very religious. And his religion says that a man and wife are married for life. That is the main reason he kept returning to Genevieve and his daughters time after time—even though he and Genevieve were incurably incompatible. It wasn’t, as some have charged, only because he was down and out. It was his conscience that drove him back to his family—and that, more recently, took him to Genevieve’s bedside when she was hospitalized. The only reason he doesn’t see his daughters more often now—outside of the time-consuming work demands he has placed on himself—is that he feels guilty because he has a sixteen-year-old daughter and a twelve-year-old daughter who live in another apartment a few blocks away from their father. This arrangement, to Jackie, is wrong. But there is nothing he can do about it.

So he gads about, buys another sports jacket, formulates another format. Every day he gets richer, busier, more boisterous.

Those who know Jackie and love him rejoice for the pleasures he gets out of life, but they know they are momentary and monetary. When, they wonder, will he be able to relax and be happy?

THE END

—BY RICHARD MOORE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE APRIL 1955