Love Is Never A Mistake

A little girl lay by the side of a dusty, lonely road. She was scarcely conscious; badly hurt. The sun beat down upon her crumpled body and she whimpered with pain. ‘I am going to die,’ she thought. And then a fine handsome cowboy galloped up on his horse and rescued the little girl. She looked at him and saw that it was Hopalong Cassidy. ‘Where are you taking me?’ she asked.

“ ‘To Hollywood, to be a movie star,’ said Hopalong.”

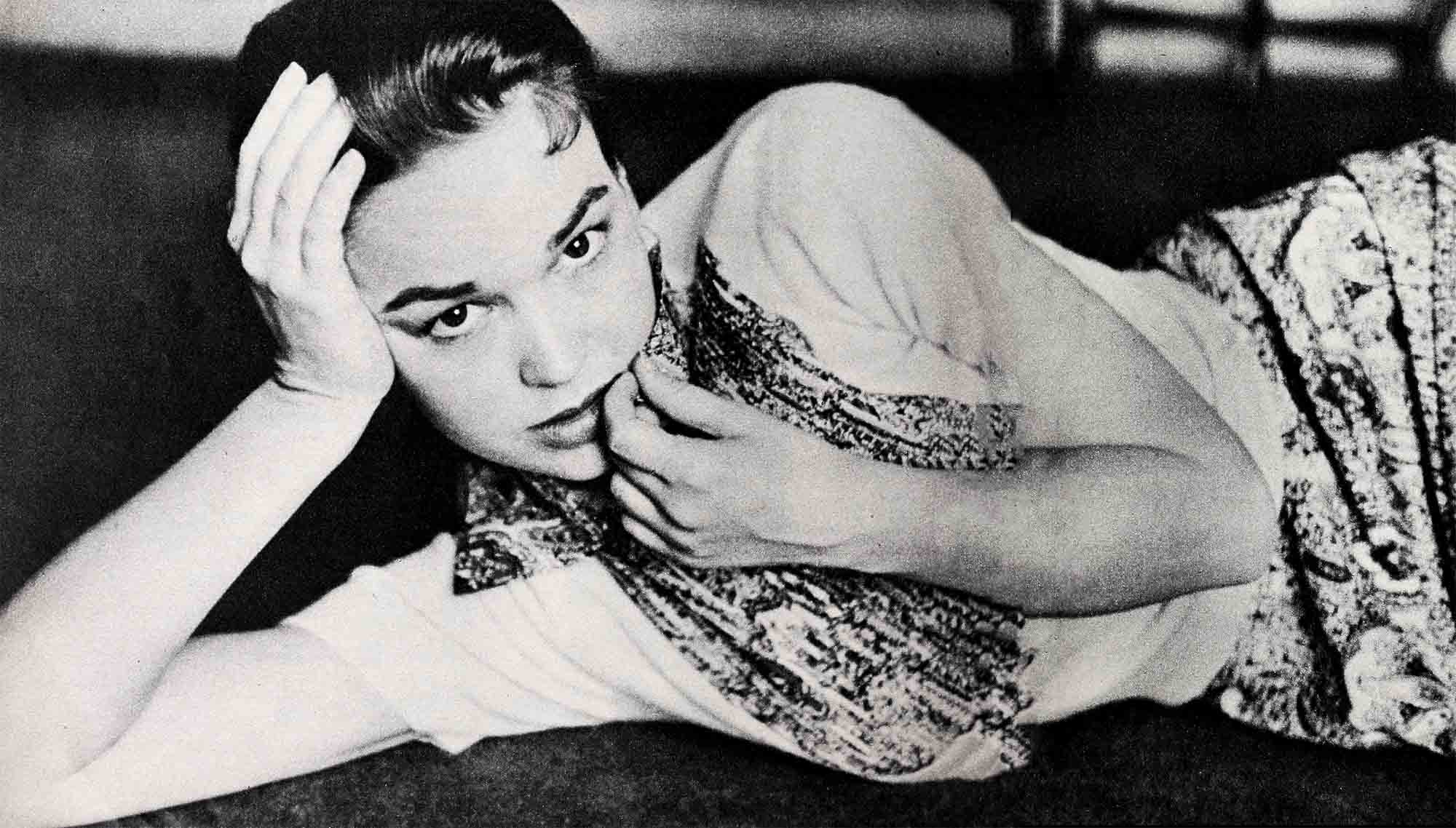

Kathy Grant tells this story—a dream from childhood—to show how she became a movie star. “Not that simple, really,” she laughs, “but I’ve had the dream a long time. I had lots of dreams to keep me company when I was growing up. I must have been lonely,” she admits candidly, “but I know it was my fault. I had a lot of imaginary playmates, though. But the only one I remember by name is Lulu—the bad one. She really was a little devil. Every time something bad happened, Lulu was to blame.”

“And who is to blame for unhappy things today?” I asked. Kathy knew what I meant, for she had promised not to evade the question of her romance with Bing Crosby. In the two years they’d gone together, their romance had hit the gossip columns, the front pages and the cover lines of magazines throughout the world. Some stories had been kind, but many had been cruel, filled with innuendos and misplaced motives. Reading some of them I’d thought, “How can a youngster like that take it.” I asked Kathy and listening to her talk about herself and about her childhood, some things were easier to understand.

“I was born Kathryn Grantstaff, not Kathy Grant,” she explained, “in Houston, Texas. When I was a little girl, my family moved from Houston to the tiny town of West Columbia, and I lived there all during grade and part of junior high school.”

Some two hundred miles away from West Columbia, in Robstown, Kathy’s Aunt Frances—her mother’s sister—and her husband Leon Sullivan lived. “Aunt Frances and Uncle Leon didn’t have any children of their own,” Kathy explained, “so we visited them on summer vacations and holidays. Robstown was our second home.” At twelve, she went to live in Robstown with her Aunt and Uncle.

“Leaving my family, moving to a strange town—it all seemed painless to me,” she says without much feeling, “I made a few friends, but gradually my imaginary playmates took precedence over my real ones. It was here in Robstown that I dreamed of Hopalong and Hollywood. I don’t remember where the thoughts began—or ended,” she adds seriously, then suddenly, smiling, “Silly isn’t it?”

But those who remember Kathy then know it was not silly. She was withdrawn and uncertain and unable to make an effort to win acceptance among her fellow students. There is still pain for Kathy when she speaks of those days, and still surprise that she was so often misunderstood.

“I didn’t know how to go about being popular,” she recalls somewhat ruefully. “At first I didn’t even realize I wanted to be. I just got off to a bad start with the kids,” and she let her thoughts wander a moment. “I guess right from the beginning I did.”

“I’ll never, never forget the first party invitation I received from a girl who was very popular in school. But Aunt Frances and Uncle Leon and I had planned a picnic for the same afternoon. I loved those picnics—and I didn’t go to the party. The next day I found out it had been a surprise party for me. Isn’t that awful? A sort of introduction to all the kids. Their opinion of me was pretty low. They thought I was a snob.”

Kathy recalls: “Aunt Frances was really distressed by it all. She spent many weary hours trying to impress upon me the importance of social graces and etiquette.”

At the time she listened quietly and agreed to change her ways, but “deep inside something rebelled against following a fixed pattern—just as it does now. I didn’t mean to hurt people. …” and then abruptly she adds, “Aunt Frances was very good to me—really. I just didn’t appreciate it all. I was pretty headstrong and there were times I made her pretty angry, too. She had every right to be, but then again, I thought, so do I.

“My aunt sewed beautifully. She made all my clothes. The trouble was I wanted clothes that were different. She told me she knew best. I remember, during my Junior year, I was invited to the Junior-Senior Banquet. I knew just what I wanted: a red strapless evening gown. But Aunt Frances made me a white organdy one with puffed sleeves, very kiddish and proper. How I hated it. We argued a lot. My own mother was far away. I used to think that perhaps she would have understood some of the things I couldn’t make Aunt Frances understand, now I realize I was silly. I adopted another ‘mother’ in Robstown, Bea Jackson, who was our Rainbow Girls adviser. Almost immediately she became “Aunt Bea” to me. I ran with all my troubles to her and she’d listen patiently and say, ‘but Kathy, don’t blame your auntie. She only wants you to be perfect.’ I remember crying out bitterly one day, ‘But I don’t want to be perfect. I just want to be happy . . . to be me.’ ”

Happiness had many faces and Kathy Grant had yet to find the one which best suited her. She was still a “loner”—as she is today—but the need for acceptance, a desire for love and warmth and roots—drew her deeper into school activities. She went out for athletics, dramatics and as many school functions as she could manage—and she made friends. And without her knowledge, a group of fellow students entered her photograph in a beauty contest. She won, and this, the first of several awards, proved a turning point in her life —a point where dream and reality suddenly began to fuse.

“At sixteen,” Kathy explained. “I was chosen Texas Rodeo Queen. One of the judges was Art Rush, who was also Roy Rogers’ manager. I talked with him about my dreams of a picture career.

“ ‘Finish school. Grow up, Kathryn,’ was his recommendation. ‘Then think about it.’ Although my Mother, Dad, Aunt Frances, Uncle Leon and a schoolteacher had all said the same thing, it was Art Rush who carried authority,” Kathy admitted. “So I graduated from high school and went on to the University of Texas, with thoughts of Hollywood, though, still in mind.”

A year later she won second place in a “Miss Texas” contest, and the following summer left for Hollywood, where she secured a screen test through Art Rush’s help.

“Hollywood’s a confusing place for a teen-ager on her own,” Kathy explained. “Suddenly, there was no Aunt Frances, no Uncle Leon, no Aunt Bea. And I was only sure of one thing. I wasn’t going to fight the battle of a girl alone in Hollywood. A home and family atmosphere were too important to me. I didn’t see myself living alone in some furnished room—or even in a girls’ club. I needed to be with a family. And I needed to go on with my college work, so I enrolled at UCLA and lived with a family near campus. They became my new elders. They were wonderfully understanding.” And Kathy might have added, they gave her the needed understanding and affection she’d always searched for.

Later on, when she went back to the University of Texas for a six-week summer course to complete her credits for her college degree, she met in her government class, “Aunt Mary Banks”’—a bright charming and friendly woman who was taking the course because now she had time for study with her own children grown. The Banks family—Gilbert Sr., their daughter Marilyn, who is about Kathy’s age, and Gilbert Jr., who is in his teens—became her family too. Kathy speaks of the latter as my “sister and brother.”

Although Kathy has her own apartment, when Mr. Banks moved his business to California, she made the Banks her real home. Here roots were firm and deep and their understanding made the months to follow less painful. “But I’m trying to be a grown woman now,” she says, “so I’m determined to try to make my own home out of this apartment.”

We were in her apartment when she told me about Bing Crosby. On her coffee table lay a book called “The Consolation of Philosophy.” Alongside of it were a decorator’s plans for redecorating the apartment—Kathy’s current big project.

They seemed to symbolize what’s important to Kathy. Her thirst for knowledge, her need for a philosophy—and her yearning for a home.

The story of Kathy Grant and Bing Crosby is truly the saga of all star-crossed lovers, from the moment of their meeting to their ultimate break-up. They are not the first couple who have bridged the chasm of two decades to fall in love. But they ended it as they feared from the beginning that they must.

“The difference in our ages meant nothing,” Kathryn said softly. She smoothed back her already smooth dark hair and a strained expression came over her face.

“We were two human beings. We loved each other. He is a lonely man, a gentle man. He takes his responsibilities seriously, weighs them carefully. We were happy in a relaxed quiet way. We did not yet know what we learned later: that a man like Bing Crosby is not just a person. He is a symbol. Even I was a symbol. And one doesn’t disturb a public symbol without paying an exorbitant price.”

Later, Mary Banks added further to the story:

“Kathy told me about Bing as soon as they met. She wanted him to know the family. She wanted us to meet him. It was arranged. We went to her little apartment on a Sunday evening. Kathy had read in the newspapers that it was Bing’s birthday. She bought a birthday cake. She served tea and we had a lovely time. There were no tensions, no embarrassing silences. My husband and I didn’t know just what to expect, but the visit was pleasant. Nevertheless we were worried.

“They were simply wonderful together. He is a deeply quiet man at heart. Kathy is. that way too. They seemed to share a remarkable, under-the-surface level of understanding.

“There was a flowing of spirit from one to the other which went on of its own accord. This happens between a man and a woman, sometimes. Kathy has depths and wisdom far beyond her years. (She also has a very high IQ, rated tops in studio group testing.) Sometimes I marvel at her myself. It was this very depth that lessened the age difference between them, but the outside world couldn’t know that, of course.

“Already some of the gossip columns had used an item or two about them. We all felt that a great storm of public dis- approval was building up. They conducted their friendship with distinction and dignity, but I think they knew from the start that their friendship venture on unapproved ground would be difficult.”

There were those who said that Bing Crosby was interested in a young girl because he was going through a phase common among middle-aged men. There were those who said that Kathy was only interested in him because he was a big man in the picture business.

They found their targets with cruel precision, the climate of public opinion was no longer threatening a storm. The storm was raging and nearly at its peak.

“Despite this, Kathy and Bing seemed to be two happy people. Not hysterical, nor overly romantic about each other, just down to earth, and aware,” says Mary.

Some say Kathy thought, till the very end, that they would be able to work things out. She’d bought a wedding dress (and never used it). She had asked to be converted to the Catholic faith. (It was her own idea, but it was Bing’s religion). And then their relationship seemed untenable.

Mary Banks’ hazel eyes filled with unshed tears behind her glasses. She added, “We love Kathy so much. We felt sorry for her. And for Bing too.”

“We had so much fun together,” Kathy declares. “We didn’t have to talk much. I don’t like making small talk. I almost can’t. Bing’s that way too. We didn’t need small talk.”

She was silent for a moment, lost in reverie. Then she jumped to her feet and cried in a too-cheerful voice. “Let’s have some tea! I make good tea!”

She went into the kitchen and came back soon bearing the tea things. Bending over the cups as she poured, she went on:

“There’s something the economists call the climate of public opinion. The world could not accept our departure from the accepted pattern. What had started as an ideal human relationship became muddled and confused. In time we were forced to recognize that our responsibility to the . outside world was more important than our responsibility to each other. But it wasn’t easy to act on that realization. It was an intellectual decision. Emotions aren’t so easily influenced.”

The lengthening shadows of late afternoon streaked across the room. A tardy shaft of sunshine caught the highlights of a beautifully hand-wrought brass tray. Kathy’s fingers traced its carving lightly.

“I brought this back with me from Korea,” she explained. “It’s lovely, isn’t it?”

The trip to Korea, and other trips to entertain service men, had followed as an antidote for pain.

“I wonder,” she mused thoughtfully, “if it would have made a difference to people if I had announced that I was giving up my career? Would the climate have changed? I would no longer have seemed ambitious—would people have believed me then?”

She immediately rejected this notion with her next: “But I couldn’t do that! It wouldn’t have been honest!”

No, it wouldn’t, and not being honest is the greatest crime of all to Kathy Grant. What she will be, she will be on her own—as always. And what she must do, she must do because of her inner convictions.

The doorbell rang and Kathy ran to answer it. She let in a tall, lanky, good-looking boy and gaily announced: “Oh, meet Guil, my adopted kid brother.” And in a moment, Kathy had shut the door on her memories.

“Mom says I’m to bring you back to the house for dinner. It’s your turn to do the dishes.”

And as Guil bent down to help her into her jacket and take the chocolate cake she was bringing over for dinner, Kathy turned suddenly towards me, serious for a moment, and said, “Answering your questions. No, love is never a mistake.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1957