The Made Him A Star—John Saxon

It all began one afternoon late in September, 1953. Carmen Orrico hurried across Manhattan’s traffic-jammed Forty-Second Street and headed for the editorial office of Macfadden Publications. He had a modeling appointment, the third after-school modeling job he’d gotten. “I don’t mind the work,” he’d told his parents. “I enjoy meeting the people and I’m getting experience. Besides, the money’s good, too.”

He bought the late evening newspaper, then turned into the huge building, asked the elevator operator for the seventh floor and checked his watch. “Five minutes to spare,” he muttered and, getting off, found himself in the reception room.

“Where are the True Story offices?” he asked the receptionist.

“Go left,” receptionist Jean Hanson told him, “and ask for the art director.”

Half an hour later, slumped against an alley garbage can, his face and arms made to appear bruised and bleeding, Carmen posed for the picture on this page—the picture which was to make him a movie star.

“It was for a True Story novelette” John Saxon explains today. “. . . A kind of off-beat shocker on delinquency called ‘Street-Corner Girl.’ ”

When Fred Sammis, then editorial director of Photoplay and other Macfadden magazines, was shown the color-photo transparencies of John, he says, “I realized immediately that the boy had a photographic quality which could be just as good in movies as in stills. I had the transparencies airmailed out to Photoplay’s coast office, marked for Henry Willson, the same agent who sent Rock Hudson and Tab Hunter on to fame. Willson called me within a day and said he was interested. ‘I like his face,’ he explained. ‘There’s a troubled, hungry look that might come across on the screen. What do you think of him, Fred?’ he asked me. ‘He has an animal brooding look,’ I agreed. ‘A sort of sullen Tony Curtis.’ ”

Within a week, Carmen Orrico was discussing a Hollywood contract.

Carmen took his first screen test in New York. But there was only one hitch: He was not yet eighteen, legally under age. So he had to stay on in New York and continue his studies for six months, finishing high school.

“When Mr. Willson called from Hollywood,” John admits frankly, “I didn’t know if someone was playing a gag or not. I was too flustered to realize what he was saying. ‘Send the contract along,’ I managed to get out, ‘and I’ll show it to my folks.’ ”

The atmosphere around the Orrico family dinner table that evening was a mixed one. Carmen’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Anthony Orrico, were thoughtful; the two younger sisters, Delores and Julie, overwhelmed. (“If Carmen goes to Hollywood, maybe he can get us Marlon Brando’s autograph!”) Nobody ate.

Mrs. Orrico was worried about Carmen’s being an actor. “She was afraid I’d be disappointed and hurt,” he explains. She knew her only son was quiet and sensitive. Everything in Hollywood would be new and strange. He wouldn’t know anyone, not even Henry Willson, whom he’d only talked to on the phone.

As she sat at dinner, Mrs. Orrico’s thoughts skimmed back to when Carmen was thirteen. He’d talked the sixteen-year-old boys into letting him join their Ty Cobb Baseball Team. He was the youngest and the smallest—the butt of their jokes, the work-horse for their whims. Her heart still almost stopped when she remembered how an older boy had found Carmen bending over, tying his shoe in front of a locker, and had picked him up, turned him upside down, and locked him in the metal compartment for ten minutes. Fortunately, some of his friends had heard his cries and helped get him out.

Hollywood, however, was something else. Of course, he was growing up—he was seventeen. Yet, like all mothers, she worried. He would be away from home for the first time, trying for a highly competitive career. Who was there to offer a helping hand?

Mr. Orrico, a hard-working painter and contractor, was more practical about his son’s career. “If you want to be an actor,” he advised, “don’t spend your. time day-dreaming while waiting for the agent to phone. Learn your craft.”

The contract arrived from Henry Willson, and the Orricos, who had to sign it since Carmen was still under age, considered it long and seriously before doing so. Finally they did, and Carmen promptly enrolled in a drama course at New York’s Carnegie Hall.

“The boy used to come up to the office for advice during this time,” Fred Sammis explains. “It had all happened so suddenly that he was frankly quite bewildered.”

“When I look back on that period, I realize I didn’t have any dogged determination to make acting my life’s work,” John Saxon now admits. “All I know is, I had a curiosity and an intense desire to learn.”

Fate and Mr. Sammis were to cooperate in making acting Carmen’s life work, for in January, 1954, “Street-Corner Girl” was published. The caption under Carmen’s picture read: “Raf would die if I didn’t get help. There was no one to turn to but the cops—and they were looking for us, guns in hand.” And Carmen, portraying Raf, carried the job off beautifully.

When the magazine came out, all Carmen’s neighborhood buddies in Brooklyn began razzing: “Here comes the celebrity!” “Yoo-hoo, how does it feel to be a hero?” “Look at Carmen, boy model!” They held their stomachs as they choked with laughter.

But across the country the tune was different. Suddenly, within a few days after the issue appeared on the newsstands, the offices of True Story were flooded with fan mail of a sort they had never received: stacks of letters demanding to know: “Who’s the boy on page 37?” Letters and cards jammed the editorial mail bags, begging for information on an unidentified male model! “Tell us about him!” “Can we start a fan club?” “Where does he live?” “How old is he?” Reaction of this kind, to a model, rather than to a story, was practically unheard of, said the magazine’s editors.

Now Carmen’s mere curiosity developed into full-flamed interest. His burst of popularity had given him needed confidence, and he went at his drama lessons with a vengeance. The first to arrive for a lesson, he was almost always the last to leave. He became so absorbed in trying to improve that he’d often wake up in the middle of the night and find himself repeating his diction exercises.

Two months later, the day arrived that Mrs. Orrico had worried about, that Carmen had wondered about and feared. Willson wired that now would be the time to come to Hollywood.

“The morning I left New York, the temperature dropped to thirty-two degrees,” says John. “At the last minute everyone was helping me pack. My mother insisted I wear an overcoat, my sister found my rubbers and made me promise to wear them, while my father handed me my plane tickets. It was my first trip away from home, as well as my first flight.”

The boy tried not to look bewildered when the plane taxied to a stop at Los Angeles’ International Airport and he walked down the ramp. It was easy for his agent to spot him. “He was the only passenger wearing an overcoat and carrying rubbers,” Willson laughs. “The mercury was bubbling at ninety-six!”

Willson, seeing the boy was nervous and exhausted, asked him to dinner and discovered John hadn’t been able to eat in twenty-four hours. Pulling his convertible up to the nearest restaurant, he predicted: “There are going to be lots of steaks in your future!”

Carmen beamed. But his face clouded minutes later, when, over steaks, Willson continued in a more serious vein, “. . . But what’s not going to remain in your future is Carmen Orrico.”

He reacted instantly to Carmen’s puzzled expression. “This change we’re making immediately. Your real name, Carmen Orrico,” he insisted, “is too hard to pronounce. We want something that is easy to say and remember.” Willson, noted for thinking up Rock, Tab and Rory dubbings, suddenly beamed. “That’s it!” He snapped his fingers. “Rip Saxon. How does that sound?”

It didn’t sound right. Although he was excited, Carmen wasn’t too awed by his sudden success to speak up when he felt strongly about something. “It’s not for me,” he said, digging his heels deep. “I think John would be better.”

“But there are thousands of Johns, and only one Rip,” the agent countered.

Carmen knew he had enough hurdles to jump as a newcomer without the burden and ribbing caused by an unusual or phony-sounding name. “I remain firm,” he maintained. And John Saxon was the compromise.

“Johnny was the most eager client an agent could handle,” Willson says.

“I had to be,” John recalls. “I had only enough money to stay in Hollywood three weeks. If I didn’t attract attention in that time, I had to go home.”

The three-week deadline worked out to the day. First, he was taken to 20th, then to U-I, where they tested him. “I did the love scene from ‘Picnic, and everyone seemed to like it. But it wasn’t until the last day, when my money had dwindled to a few dollars, that they offered me a seven-year contract!

“Before I signed, I sent the pact back to my folks. I also explained about my name change. A few days later, they returned the papers, along with an identification bracelet with John Saxon engraved on it. It was their way of letting me know they were rooting for me.”

But the rock ’n’ roll merry-go-round John had been on suddenly slowed to a waltz, and finally to a thud. For eighteen months, he reported regularly to the studio for a drama lesson, but never once for a movie role.

“I thought I’d go nuts,” John is ready to admit. “I’d go home, eat dinner, study and sit and brood.”

And then he met artist Mark Edens, another transplanted New Yorker.

“We didn’t start out as buddies,” Edens recalls. “I was working in the expressionist school of painting, and John couldn’t understand why a face I’d paint shouldn’t always look like a conventional face. In fact, we hardly exchanged hellos until we got into an argument one day. From the debate, I suddenly realized he wasn’t being stubborn but was eager to learn.

“Many times when Id have a group of friends over, we’d sit around and talk until four in the morning,’ Edens continues. “Gradually, John edged from the fringe of the conversation into the middle of it.”

Frequently, at these hashing sessions, spontaneous entertainment would suddenly erupt. Occasionally, the late James Dean would act out a Midwest epic in which he played all the roles from the shy schoolboy to the cracker-barrel philosopher. Others would do improvisations, and John would do vignettes about his native Brooklyn and the various nationalities that lived in his neighborhood.

In the meantime, Jess Kimmel, head of talent development at U-I, was assisting John at the studio. He used a firm hand, a non-kid-glove treatment. “For eighteen months,” Kimmel says, “Johnny saw young players, signed much later than he, get role after role, while he seemingly stood still. With no part to bolster his confidence, he could never accept himself as an actor. Even after almost two years in Hollywood, Johnny hadn’t gotten past the ‘don’t call us’ stage. He was discouraged.”

John was never self-charmed by the fact that he was under contract. “He had to be kept busy,” Kimmel confided. “So, in the months that followed, I had him do everything from interviewing Jose Ferrer, playing a fifteen-year-old, reciting Shakespeare and portraying the sensual hero in ‘The Girl on the Via Flaminia.’ ” The only interruption in the routine took place when John was given a bit part in “Running Wild.”

“I wanted to stretch his talent and imagination, and when the part of the bewildered boy opposite Esther Williams in ‘The Unguarded Moment’ came along, I saw: ‘He’s the one to play it.’ ”

But to the director, producer and star, John was an unknown quantity. They insisted on testing six name players. John won the role, though.

Kimmel’s confidence was more than rewarded in the praise notices from the critics. When “The Unguarded Moment” was finally shown, the fan clubs were pouring in mail, bombarding the studio and jamming the magazine mail bags: “Please tell us about John Saxon!” The studio caught surprised, searched around for other pictures but couldn’t find any!

Johnny, however, was taking all the attention in his stride, reporting to classes regularly. “I’m glad I did,” he grins. “That’s where I met Gia Scala.”

The Italian beauty had just arrived in Hollywood as one of the finalists in the world-wide search for someone to play Mary Magdalene. When they met in class, John greeted her in Italian. “It was like a touch of home,” Gia says. “I’d seen Johnny the minute I entered the room. With his unruly dark hair and thick black eyelashes, who could miss him? ‘Who is that good-looking boy?’ I asked one of the other kids.”

From then on they were friends.

“We’d use our Italian as a secret signal,” Gia laughs. “At a boring party, Johnny would mumble a few romantic-sounding Italian phrases, really meaning, ‘Shall we get out of here?’ ” And they’d leave.

At this point, John and Gia are much too career-minded to take their dates seriously. And so Johnny’s name has also been linked with Susan Kohner, Vicki Thal, Helen McCormick and Luana Patten from time to time. As John explains, “I get much too upset over career problems to take on marriage now.”

However, he does have definite ideas on the type of girl he wants for a wife. “Not the aggressive kind,” he states flatly. “Naturally, I don’t expect her to agree with everything I do, but still I hope she’ll be intuitive enough to understand my right to do it. Of course, my fiancée should have outside interests, but when we are married—” he continues, his dark eyes flashing, “then we should share a world of our own. That’s the way it’s been with my folks—and they’ve been married twenty-four years.”

John, whose parents are of the Catholic faith, was raised in an atmosphere of love and understanding, where there was a close relationship between all members of the family. He has had his salary prorated so he gets a check fifty-two weeks a year instead of the usual forty. That way each pay day he banks a certain portion, so he can eventually bring his parents, sisters and grandmother to California.

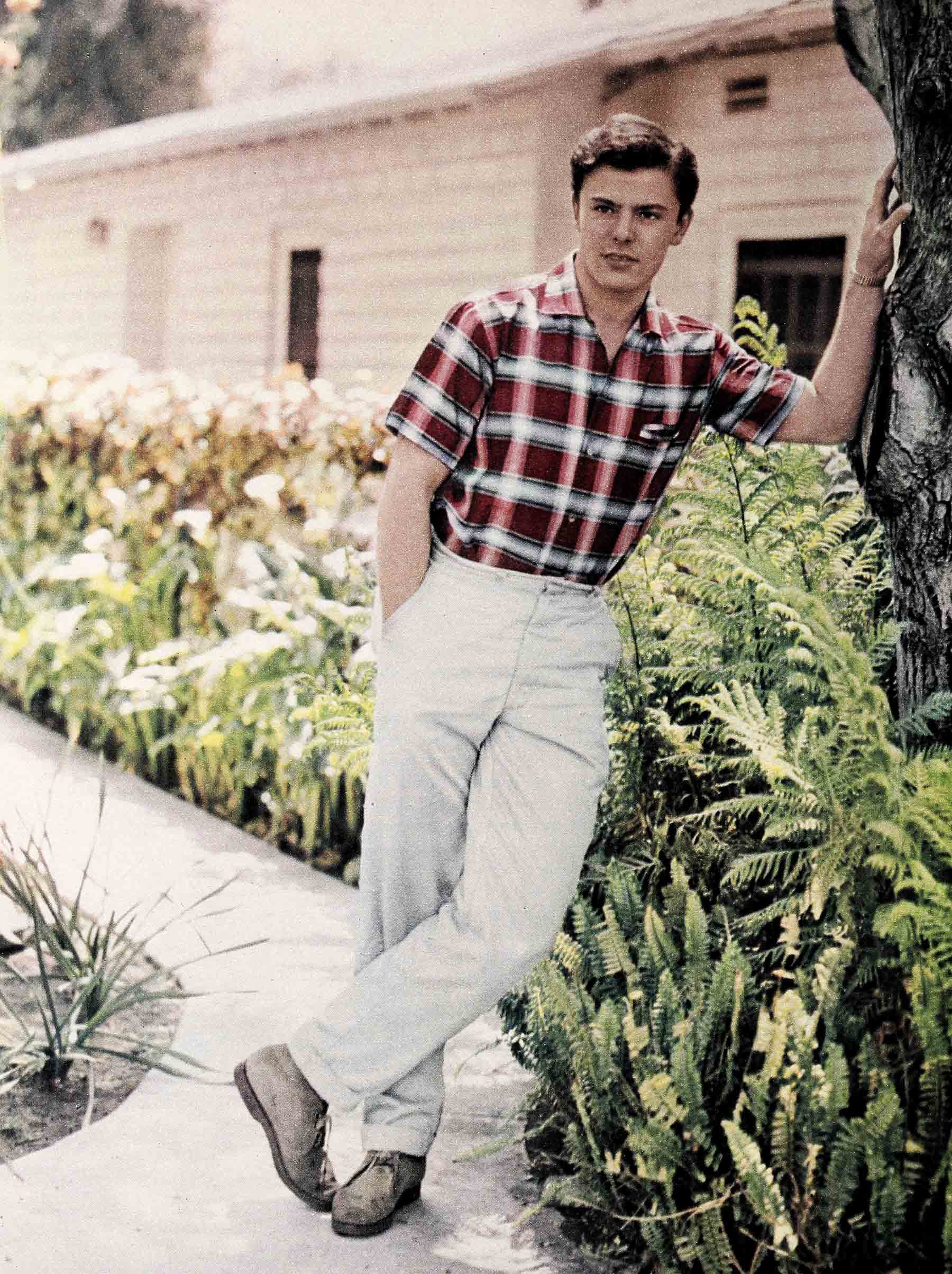

When the Orricos do come to Hollywood, they’ll find several changes in their son. He expresses himself more freely. He’s read everything from Freud to treatises on yoga. His face has firmed from an inexperienced teenager’s to a purposeful adult’s. Emotionally, although still not demonstrative, he isn’t afraid to speak up for what he admires.

“When I came to Hollywood,” he confirms, “I had only six months of dramatic training and knew no one in show business.” Now he’s made it, has had his contract rewritten, receives star billing and drew almost as much fan mail as Sal Mineo from their film “Rock, Pretty Baby.” John looks forward anxiously to his next picture, “Summer Love.” This breeds self-satisfaction—something his folks have already noticed.

“But he’s wearing his success well,” says his father. Happiness is written right on John’s face these days, whether he’s riding down a Hollywood avenue in his red MG with its rear window sign that reads “Built in Africa by ants,” or discussing his next movie. He shows it in his big smile and friendliness and co-operation.

He’s not mastered, though, the knack of feeling completely at ease with people and in situations. When upset, he still lapses into Italian, still has the New Yorker gait—seven paces ahead of the leisurely Californian. He still has an unrelenting individuality, which sometimes works to his own disadvantage.

An example of one of his own blunderings is an embarrassing moment Johnny tells on himself: “Just before I came to Hollywood, my drama teacher suggested I see Jose Ferrer, who was appearing at City Center in ‘Cyrano.’ I didn’t need any urging, for he’d always been one of my favorites. I was standing outside the theater, watching the marquee lights blink his name. I guess I was imagining for a minute or two that his name was mine, for when the crowd started moving in for the first act, I carelessly tossed my cigarette toward the street without looking. Just then I heard something, turned around and saw that I’d thrown it right in the face of Jack Palance.

“On my first day in Hollywood, my first time in a studio, my first lunch in a commissary, and my first introduction to a star—you guessed it—my agent introduced me to Palance. I was all mumbles and fumbling when I spoke and all thumbs when I tried to shake hands. I thought sure he recognized me as the thoughtless kid who’d thrown the lighted cigarette on him. I couldn’t relax, although he was friendly and didn’t even mention the incident. Later, I learned he’d forgotten the whole thing, and hadn’t even known it’d been me. I had to open my big mouth and tell him! At least my conscience was clear!

“Right after this, things looked up again. As I was leaving the commissary, a girl rushed up to me, all smiles, and sighed, ‘May I have your autograph?’

“I was so stunned I couldn’t even react at first. When I came to, I was so pleased, I gave it to her.

“ ‘Who’s he?’ her girl friend asked.

“ ‘I don’t know,’ the first girl shrugged, walking away, ‘but he ought to be a movie star.’ ”

Today that sentiment is being echoed by Johnny Saxon’s ticket-buying fans, who started the ball rolling and pushed him to stardom. The letters demanding to know “Who?” provoked action. A motion-picture magazine editor sensed the trend and quietly channeled it to the attention of the powers-that-be.

Johnny’s come a long way since posing for “Street-Corner Girl.” The road has been conspicuously lacking in press, publicity or talent-agency influences, studios or photographers—the kinds of businesses usually claiming credit for “discoveries” and pushing them hard.

Serious-minded John is working hard to stay where fans, fate and Photoplay have put him. As he himself says: “From now on, it’s up to me.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1957