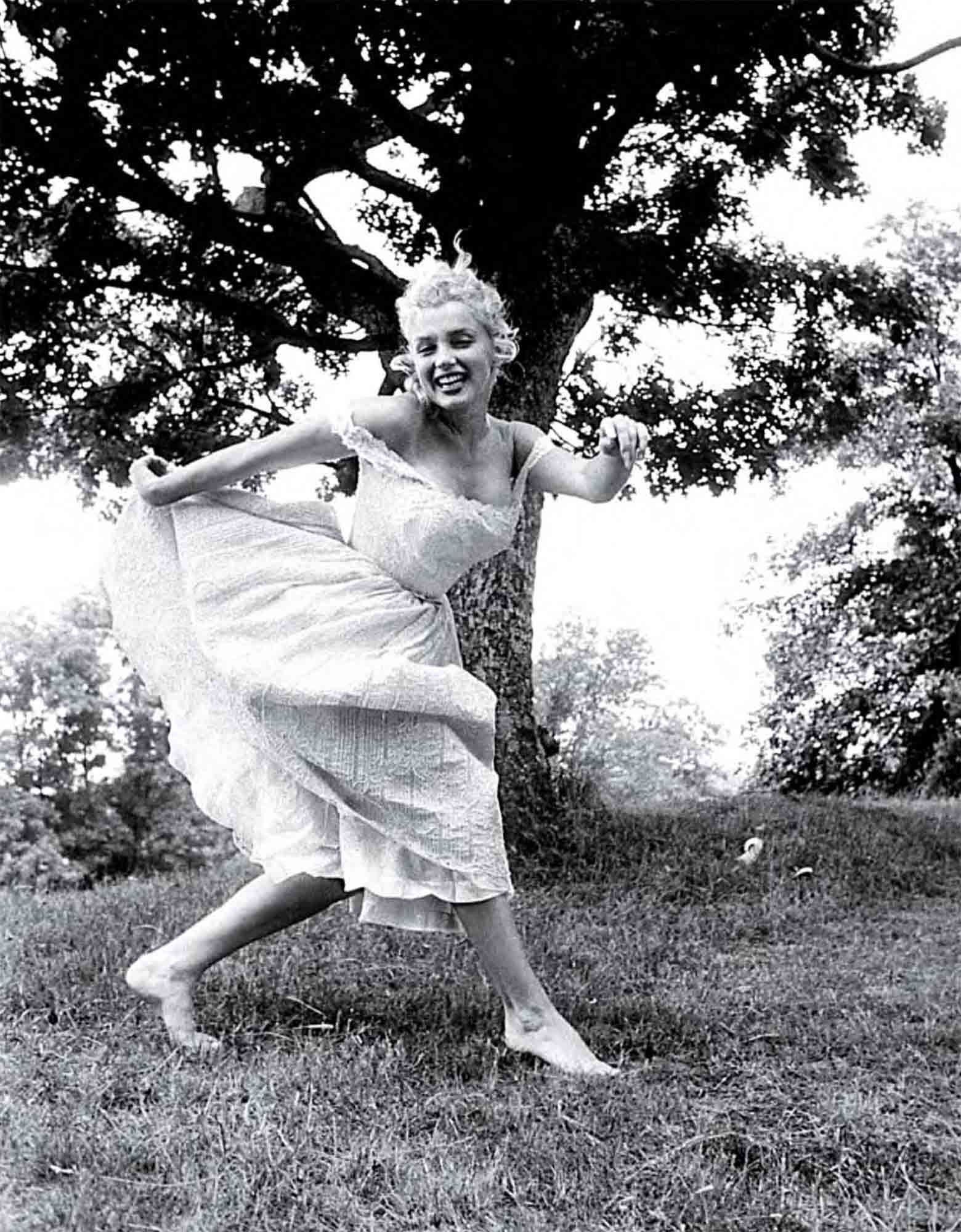

Marilyn Monroe

PART III

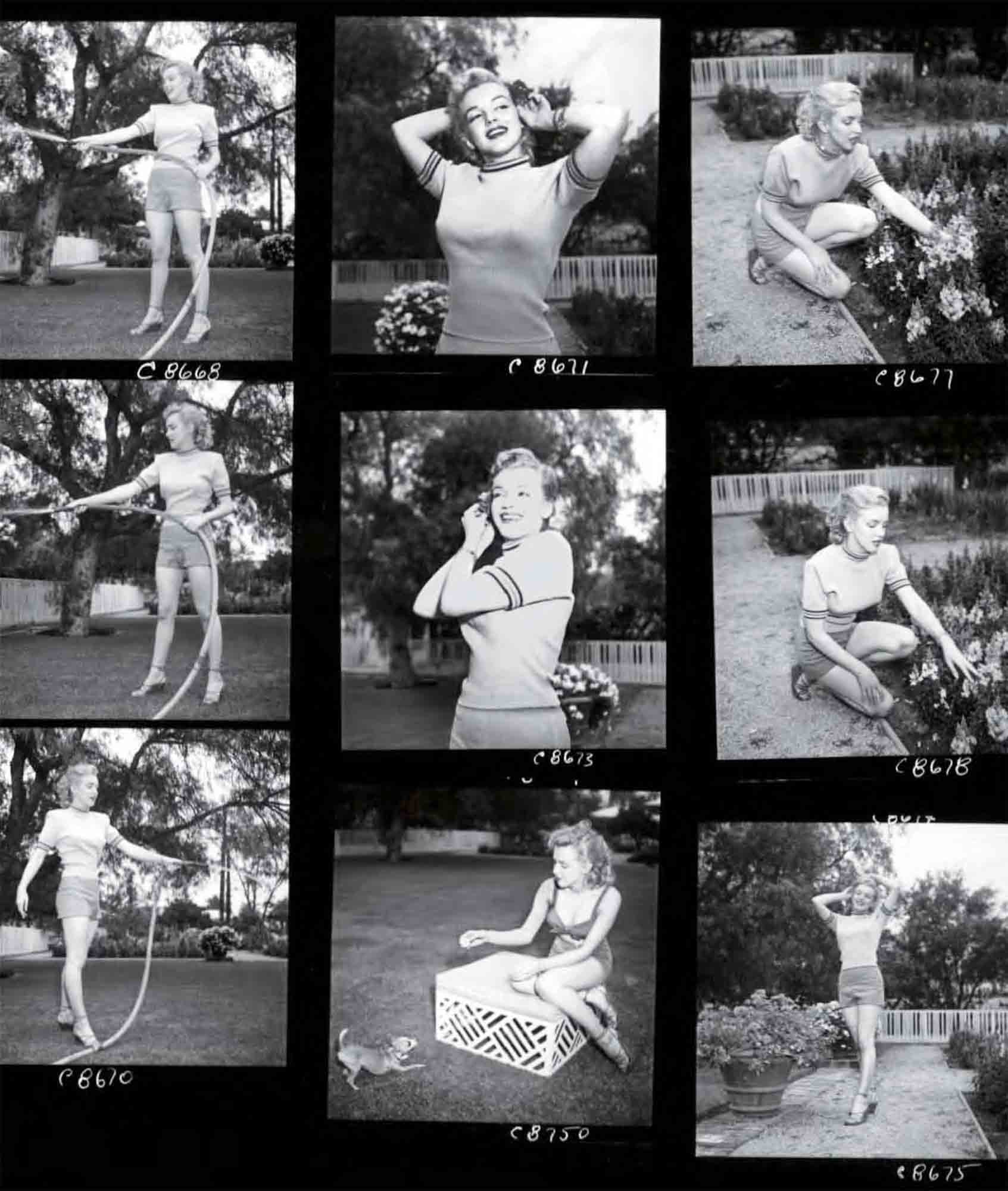

Emmeline Snively, who ran the modeling agency that employed Norma Jeane Dougherty, commented years later that girls would often ask her how they could be more like the woman who had become Marilyn Monroe. “I tell them, if they showed one tenth of the hard work and gumption that that girt had, they’d be on their way. But there will never be another like her.”

While that is no doubt true, Monroe’s singularity wasn’t immediately apparent to Twentieth Century-Fox’s filmmakers, who used her for small parts in a couple of forgettable vehicles, Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! and Dangerous Years, both filmed in 1947. After one year, Fox dectined to renew Monroe’s contract. She signed a six-month deaf with Columbia Pictures and was given a big role in a bad film, the tow-budget musical Ladies of the Chorus. In that 1948 movie, Monroe first displayed her velvety singing voice—to the precious few patrons who bought a ticket. Columbia, too, opted not to extend her contract, but her association with the studio would have lasting benefits, since it brought her into contact with the noted drama instructor Natasha Lytess, who would continue to coach her for several years.

For a time, Monroe was forced to resort to one-picture agreements and a renewed emphasis on her modeling career. She may have resorted to prostitution as welt during these early years. One former friend told biographer Donald Spoto that Monroe had bartered sex on Hollywood’s side streets in exchange for meals. She was barely 20 at the time, very much on her own, and surety desperate to make ends meet—but there is no consensus. Likewise, just as her various biographers differ in their conclusions regarding any casting-couch liaisons, there is little agreement on speculation as to how many abortions Monroe may have undergone in her lifetime. The estimates range from more than a dozen, by one count, to none, according to the actress’s former gynecologist.

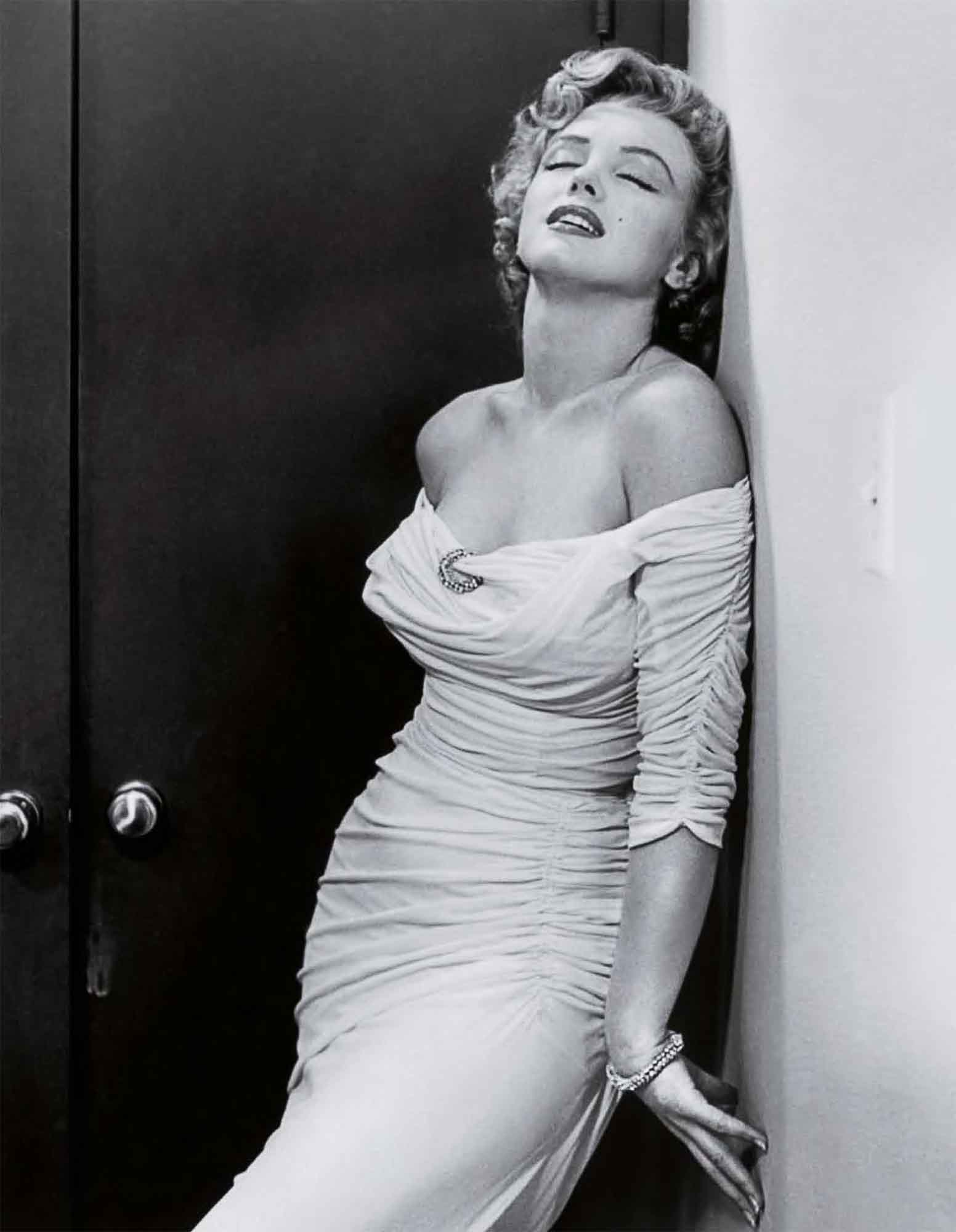

The limitless sexuality that would be such a hallmark of Monroe’s persona was openly acknowledged in one of her earliest films, the Marx Brothers’ Love Happy. When Monroe appears in the doorway of Sam Grunion’s detective agency, a male character’s monocle pops out and a billow of smoke whistles from his pipe like steam from a kettle.

“Some men are following me,” Monroe breathes to the detective Grunion, played by Groucho.

“Realty?” he says, as he watches his prospective client sashay about. “I can’t understand why.”

Monroe’s part in the movie was only a small one, but she made enough of an impression on the producers at United Artists, one of whom was legendary actress Mary Pickford, that they sent her, for $100 a week, to help promote the movie in New York and other cities ahead of its release in the spring of 1950. In that same year, two much bigger and more serious-minded pictures by heavyweight directors were released, each of which featured Monroe in a minor role. When John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle and Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Oscar-winning All About Eve followed on the heels of Love Happy, a buzz began to build about this young actress who could play funny, play dramatic and always play beautiful. In 1951, the ascendant Monroe returned to Fox, where this time she signed a seven-year contract promising her a steady income of $500 a week, with yearly increases that could push the weekly pay as high as $3,500. She appeared first in a string of B movies and then, in 1952, drew some praise for her comedic performance in Monkey Business, which starred Cary Grant and Ginger Rogers, and her dramatic turns in Clash by Night, which starred Barbara Stanwyck, and the thriller Don’t Bother to Knock, in which Monroe herself played the lead. We say “some praise” because acceptance by the public came weft before acceptance by the entertainment press.

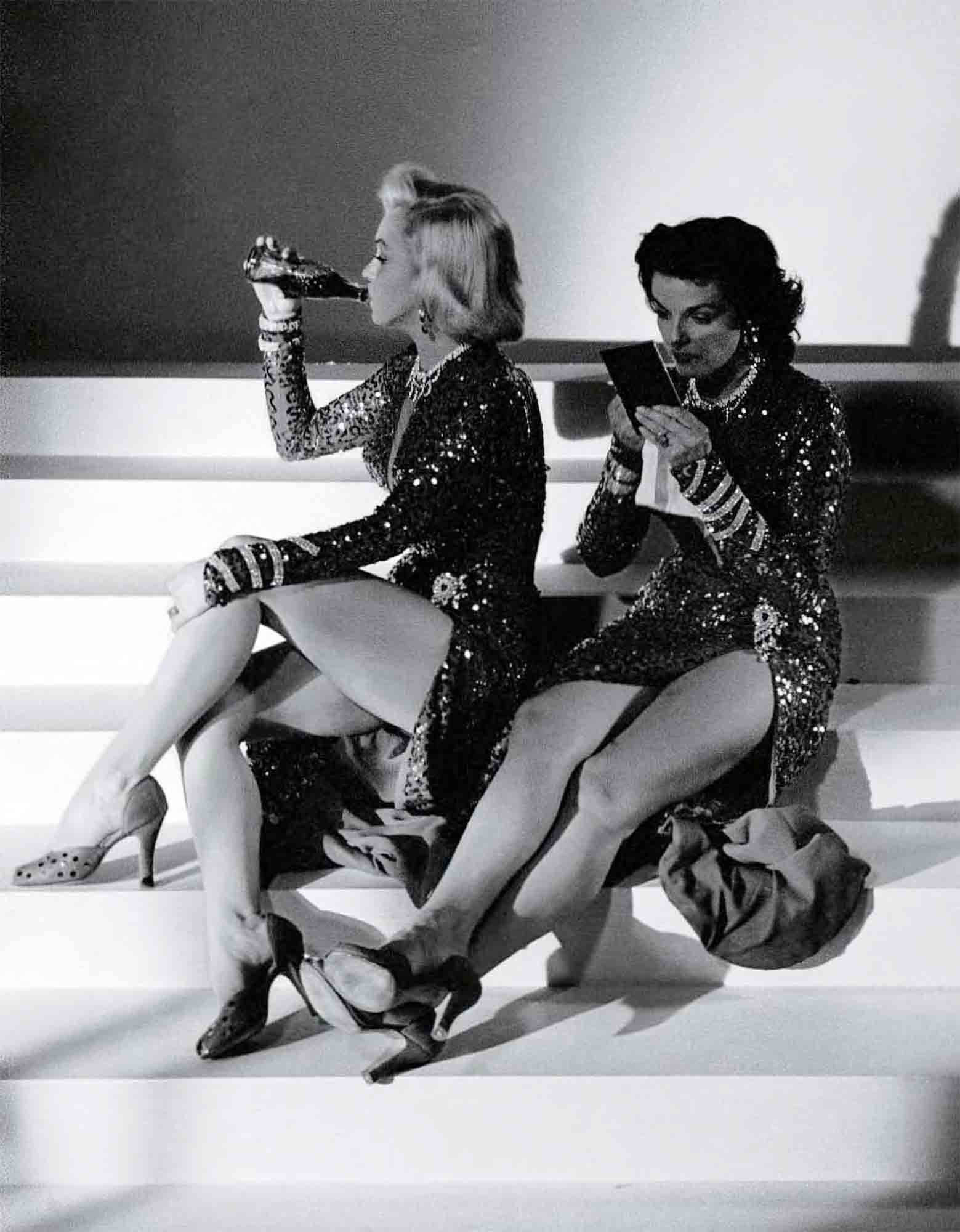

Her next cover comes the following year and is shared with fellow glamour queen Jane Russell, her costar in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

Whatever the critics’ opinions of her talent, Monroe was now on the fast track to stardom. Thousands of fan fetters were arriving each week, and across the land there was, according to a 1952 article in Time magazine, a “loud, sustained wolf whistle’’ emanating from the doors of the nation’s barbershops and garages. That whistle, accompanied by howls of outrage from some sectors, grew positively deafening when a decision that Monroe had made came back to haunt her. In 1949, the struggling actress had posed nude fora calendar for $50. Now, in 1952, Fox executives were hearing rumors that the naked blonde in the scandalous shot was none other than their young starlet. And the firestorm only gathered heat the following year when the picture was selected as the first Sweetheart of the Month centerfold in the debut issue of Playboy magazine. In addressing the brewing controversy with a reporter from the United Press wire service, Monroe exhibited a disarming cheerfulness that played weft with her public. “Why deny it? You can get one anyplace,” Monroe said of the calendar. “Besides, I’m not ashamed of it. I’ve done nothing wrong.”

Right you are, agreed a majority of moviegoers, with an overwhelming majority of the yeasayers being mate. All men desired her, and suddenly one of the most famous ones seemed to be on the verge of landing her. Right around the time of the brouhaha over the nude photo, Monroe went on her first date with the recently retired baseball deity Joe DiMaggio. She arrived two hours fate but assuaged the erstwhile Yankee Clipper with a bon mot: “There’s a blue polka dot exactly in the middle of your tie knot. Did it take you long to fix it like that?” How do we know these intimate details? Well, because Hollywood’s press departments (not to mention the stars themselves) didn’t miss a trick in quickly disseminating social items (real or fabricated) that might enhance or elevate an actor’s public image. In fact, one of Monroe’s biographers, Barbara Learning, suggests that the liaison with DiMaggio was a calculated PR move to deflect attention from the naked-pix controversy, though most other chroniclers take the advent of the Marilyn-and-Joe relationship at face value.

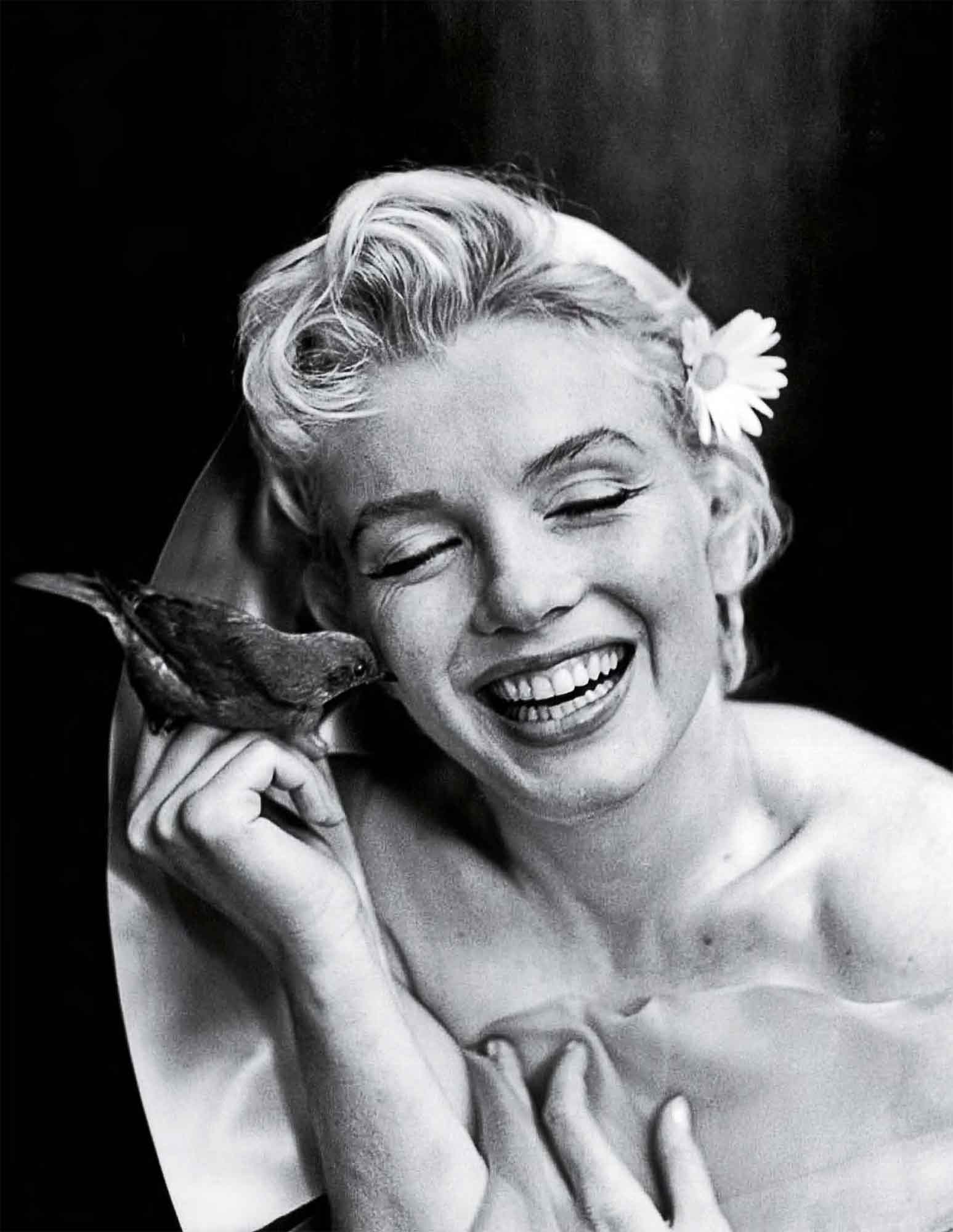

We cannot doubt that Monroe was capable of coming up with that playful witticism spontaneously and without help from Fox’s marketers. In public appearances and with the press, she showed a quick, dry wit, as well as a willingness to have sport with her obvious sexual allure. When asked whether she really had nothing on in the calendar spread, she answered, “I had the radio on.” Asked what she wore to bed nightly, she replied coquettishly, “Chanel No. 5.” Reporters loved this stuff and led the applause. Time called her “a saucy, hipswinging 5 ft. 51/2 in. personality who has brought back to the movies the kind of unbridled sex appeal that has been missing since the days of Clara Bow and Jean Harlow.” The Los Angeles Press Club presented her at one point with its annual Miss Press Club award.

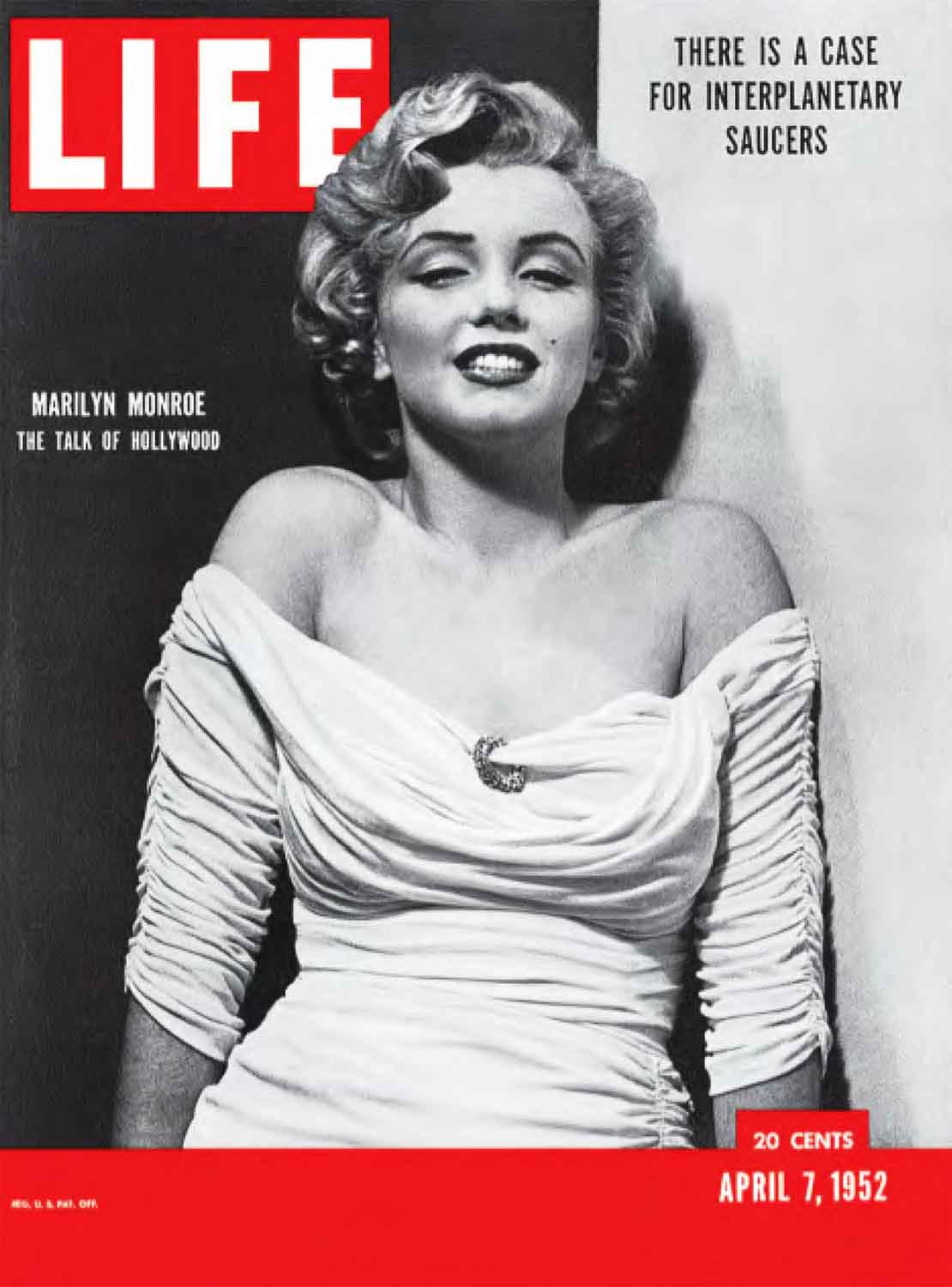

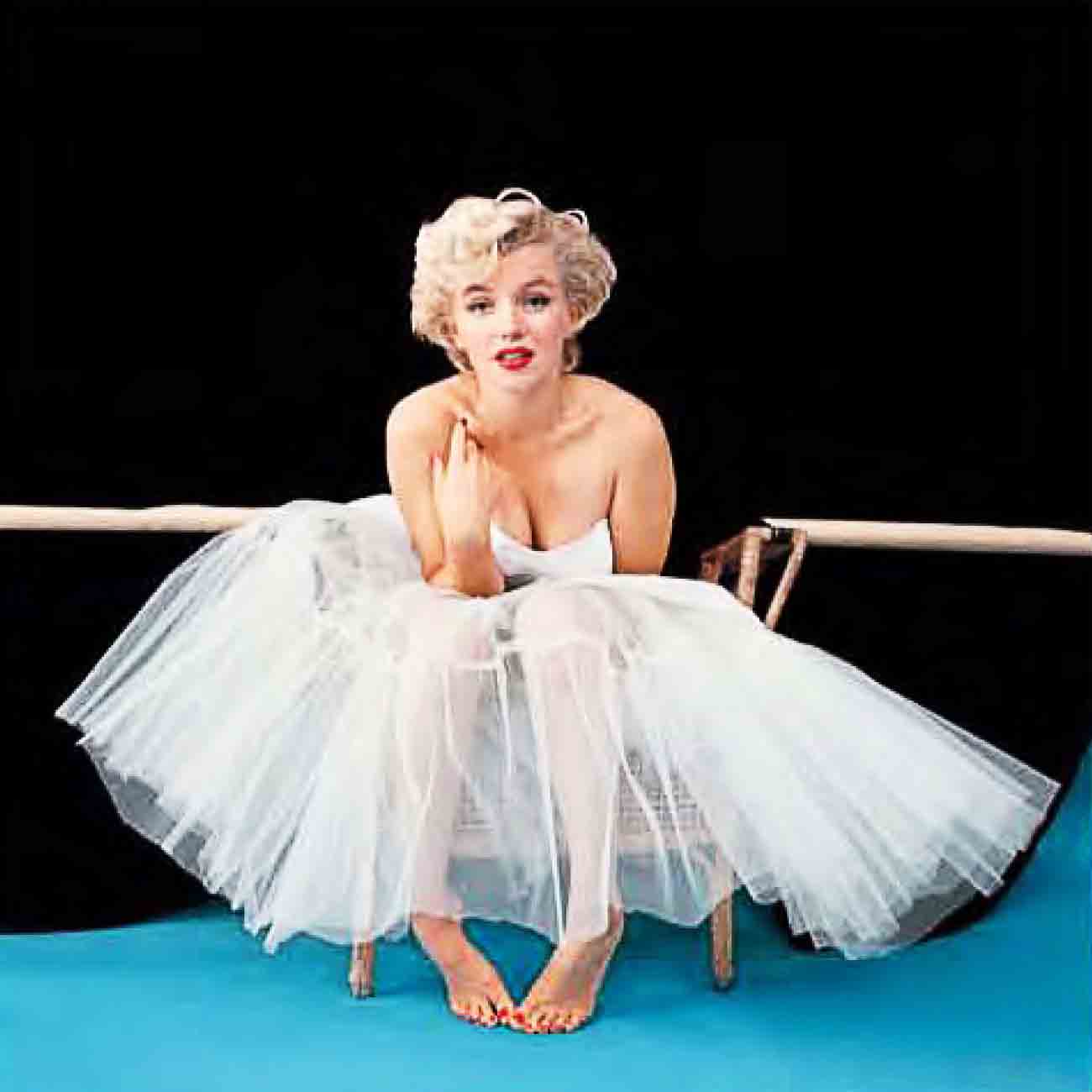

And that was only one of the earliest prizes and titles to come her way. Between 1951 and 1953, Monroe was named Miss Cheesecake of 1951, by The Stars and Stripes newspaper; the Present All GIs Would Like to Find in Their Christmas Stocking, by voting members of the armed services; World Film Favorite, by members of the Hollywood foreign press; the Girl Most Likely to Thaw Alaska, by soldiers stationed in the Aleutians; the Girl Most Wanted to Examine, by the 7th Division Medical Corps; the Girl They Would Most Like to Intercept, by All Weather Fighter Squadron Three of San Diego; Cheesecake Queen of 1952, again by The Stars and Stripes; the Most Promising Female Newcomer of 1952, by Look magazine; the Most Advertised Girl in the World 1953, by the Advertising Association of the West; the Fastest Rising Star of 1952, by Photoplay magazine; the Best Young Box Office Personality, by Redbook magazine; and the Best Friend a Diamond Ever Had, by the Jewelry Academy. Her first appearance on the cover of LIFE came on April 7, 1952: a Philippe Halsman portrait with the simple cover line THE TALK OF HOLLYWOOD.

All of this acclaim and attention was nice, of course, but still the name Marilyn Monroe was rarely, if ever, mentioned in connection with the biggest award of all—the Oscar. That situation would slowly change as the 1950s progressed. In the 1953 noir film Niagara, Monroe electrified audiences if not critics with her portrayal of Rose Loomis, an adulterous wife who plots her husband’s murder. Her quiet, smoldering rendition of the song “Kiss” and an extended shot of her wavering caboose as she ambled away from the camera—regarded as “the longest walk in movie history”—were takeaway memories. The New York Times wrote, “Obviously ignoring the idea that there are Seven Wonders of the World, Twentieth Century-Fox has discovered two more and enhanced them with Technicolor in Niagara . . . For the producers are making full use of both the grandeur of the Falls and its adjacent areas as well as the grandeur that is Marilyn Monroe.”

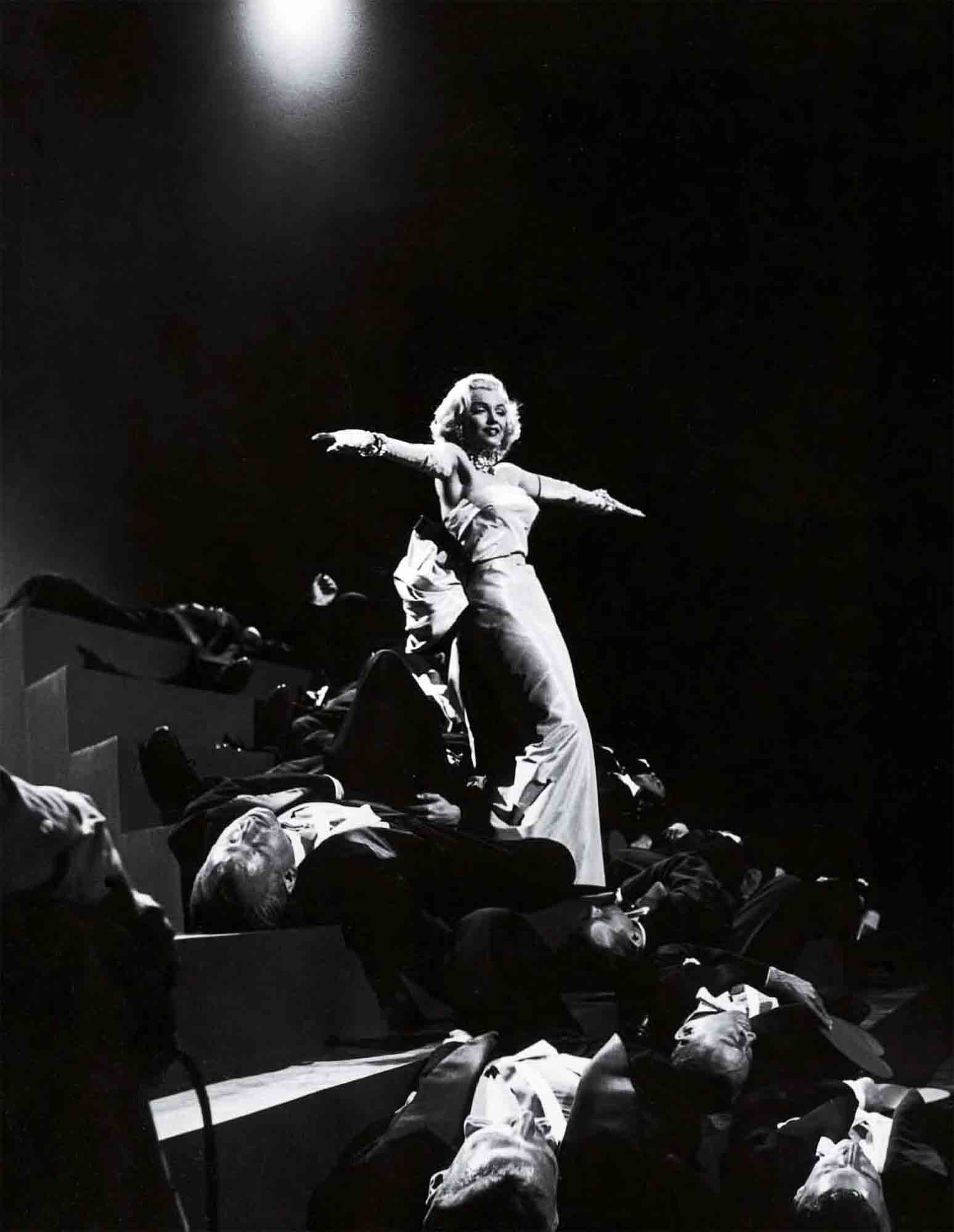

Her very next film to be released was Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, directed by Howard Hawks, and it altered the course of her career. A musical comedy about two showgirls, it featured Monroe (alongside Jane Russell) as the vapid, wide-eyed Lorelei Lee, a money-seeking missile whom men nonetheless find irresistible. This movie, too, showcased Monroe’s vocals, particularly in what would become for her a signature song, “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend.” In a shift from several of Monroe’s earlier roles, Lorelei had a defanged sexiness; a clever woman, she purposely behaved as a dim bulb because, she believed slyly, men preferred women that way. Monroe’s nimble performance helped make the film a hit, but it also served to typecast the actress as Lorelei—not necessarily an off-the-mark assessment. Many of Monroe’s co-workers and friends were always saying that she was no dumb blonde and that there were depths to her personality that were unknown to the public. “Lorelei, like Marilyn, begs the question of how much is a performance, how much is natural,“ Sarah Churchwell writes in The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe. “What is she really like?”

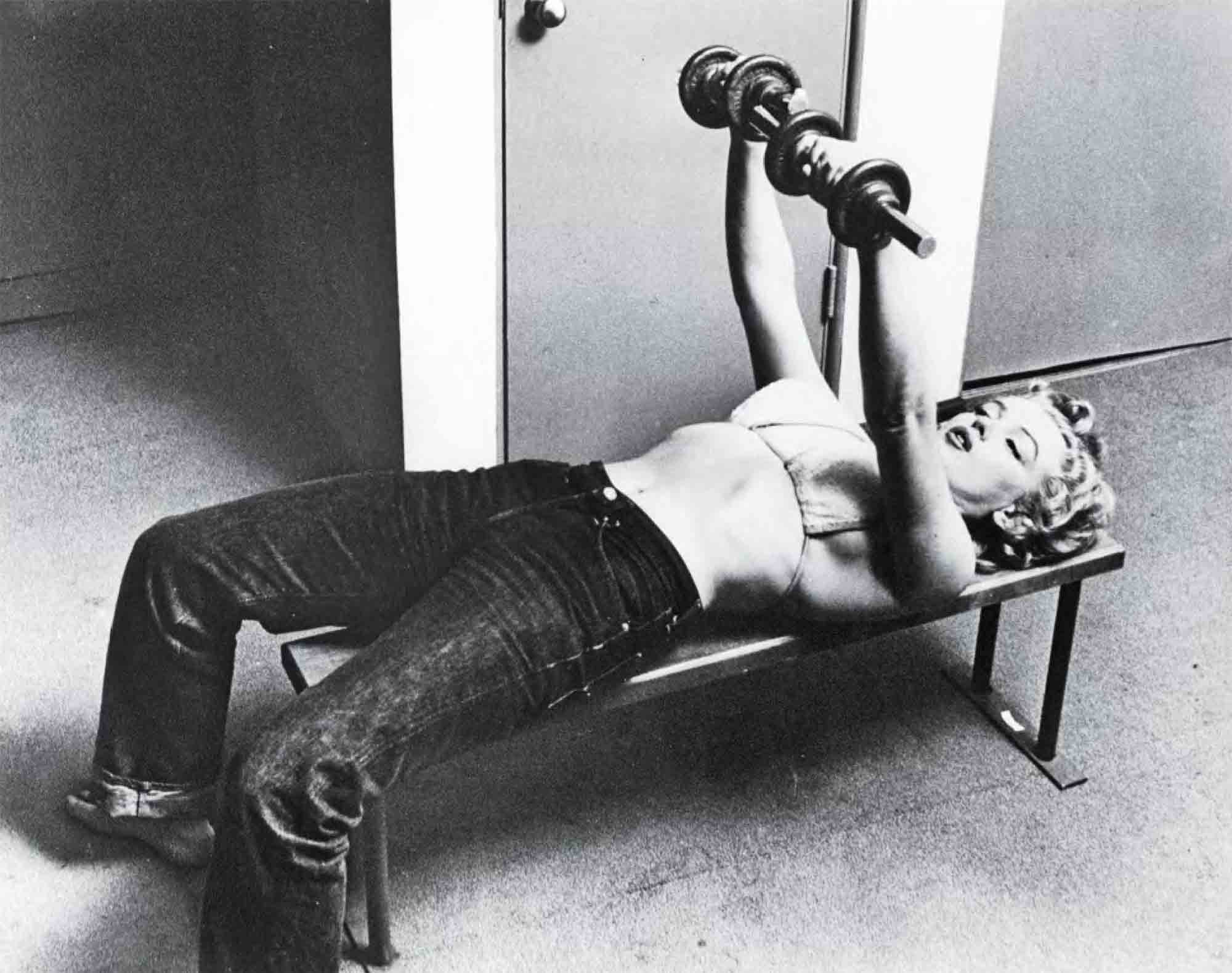

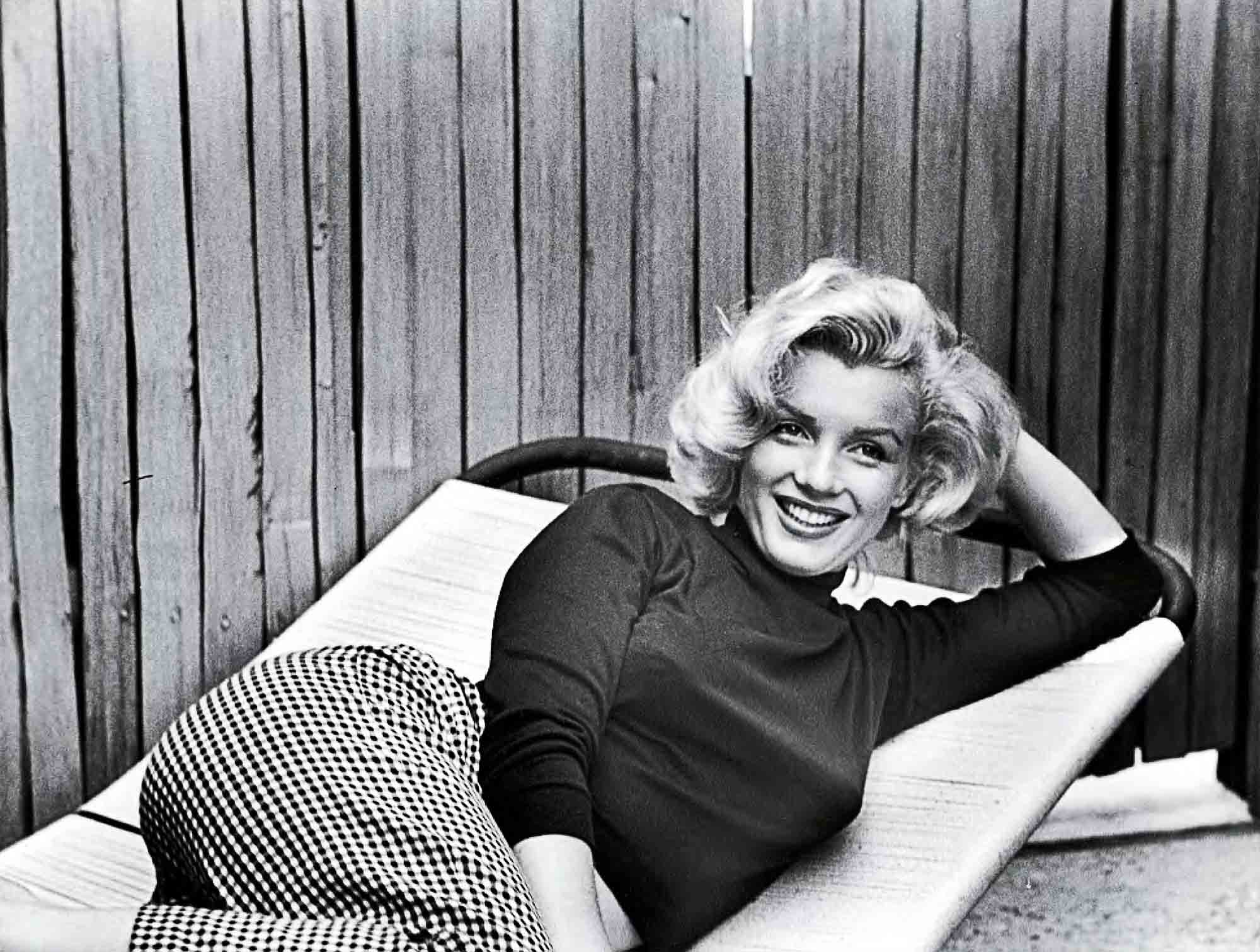

Even if Monroe was a real-life Lorelei, creating that character—or any character—onscreen was no easy task. Her difficulties on movie sets were legion, the polar opposite of the ease she showed in front of a stiff camera. She once said of how she agonized to get things right, “I’ve always felt toward the slightest scene, even if aft I had to do in a scene was just to come in and say, ’Hi,’ that the people ought to get their money’s worth and that this is an obligation of mine, to give them the best you can get from me.” Also, Monroe, who described herself to The Saturday Evening Post as “a mixture of simplicity and complexes,” was never able to leave her anxieties at the office. She suffered from crippling insomnia, then worried in turn that she would appear tired on film. She began taking sedatives at night and, some biographers say, amphetamines to counter any next-day drowsiness caused by the sedatives. She would sometimes break out in blotches or suffer fits of vomiting before reporting for work. She earned a reputation for tardiness. “A tot of people can be there on time and do nothing,” Monroe said, but it was a shallow defense.

She became known for demanding retake after retake, until she or her drama coach, whose presence on the set was anathema to directors, was satisfied. In an article on one of her productions, LIFE reported that the crew resorted to playing along with the retakes without film in the camera.

She got away with all of it. Why? Because the producers and directors were often rewarded with a fine performance. And also because many of them liked her. She was known to be gracious to colleagues, the type who would (and did) give money to crew members who, she had heard, had a sick spouse or were mourning the loss of a loved one. She was no self-indulgent diva on the set but an anguished woman trying her best.

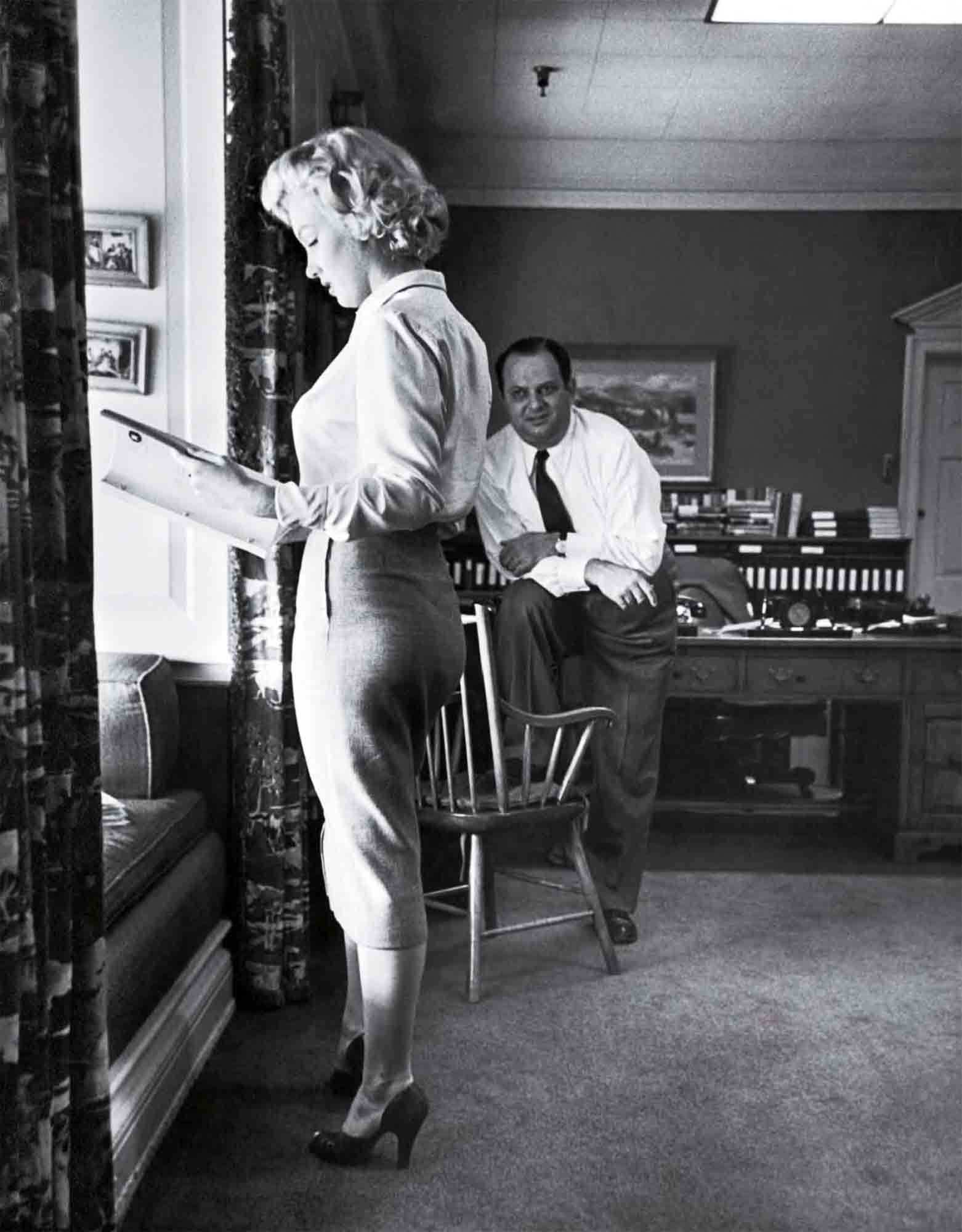

“She is not malicious. She is not temperamental. She is a star—a self-illuminating body, an original, a legend,” said Jerry Wald, a producer of Let’s Make Love, for which, LIFE wrote, the star’s delays in 1960 carried a $1 million price tag. “You hire a legend and it’s going to cost you dough.”

Said Jack Cole, a dance instructor who worked with Monroe: “She is always looking for more time—a hem out of line, a mussed hair, a scene to discuss, anything to stall facing the specter, the terrible thing of doing something for which she feels inadequate . . .

“She wants to do it like it’s never been done before.”

She once said: “I used to get the feeling, and sometimes I stiff get it, that sometimes I was footing somebody. I don’t know who or what— maybe myself.”

In a variation on that theme, she told The New York Times in July 1953, the month Gentlemen Prefer Blondes hit the theaters: “I feet as though it’s aft happening to someone right next to me. I’m dose—I can feet it, I can hear it—but it isn’t realty me.”

Who was she realty, as she became this superstar? Apparently she didn’t know, and certainty the public didn’t. To her fans, she was the golden one, the beautiful girlfriend of Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio, the screen goddess who somehow, with her wit and charm, was approachable. Who was real.

Some biographies claim Monroe was leading such a double fife during this period that she even managed a secret marriage, which to this day cannot be proved. In one version of events, a writer named Robert Slatzer competed for her affection with DiMaggio in 1952, and on October A Slatzer and Monroe, having had drinks at the Foreign Club in Tijuana, Mexico, decided impulsively to wed. They found a lawyer who performed the ceremony, but once back in California, Monroe had a change of heart, perhaps with some urging from Twentieth Century-Fox head Darryl F. Zanuck, and wanted out. She and Slatzer went back to Mexico and paid off the lawyer to erase aft evidence of the marriage. And that was

that: a three-day union. Is the story true? Slatzer, who wrote two books about Monroe and died in 2005, always said it was. There’s room enough for doubt, though, and the biographers are divided.

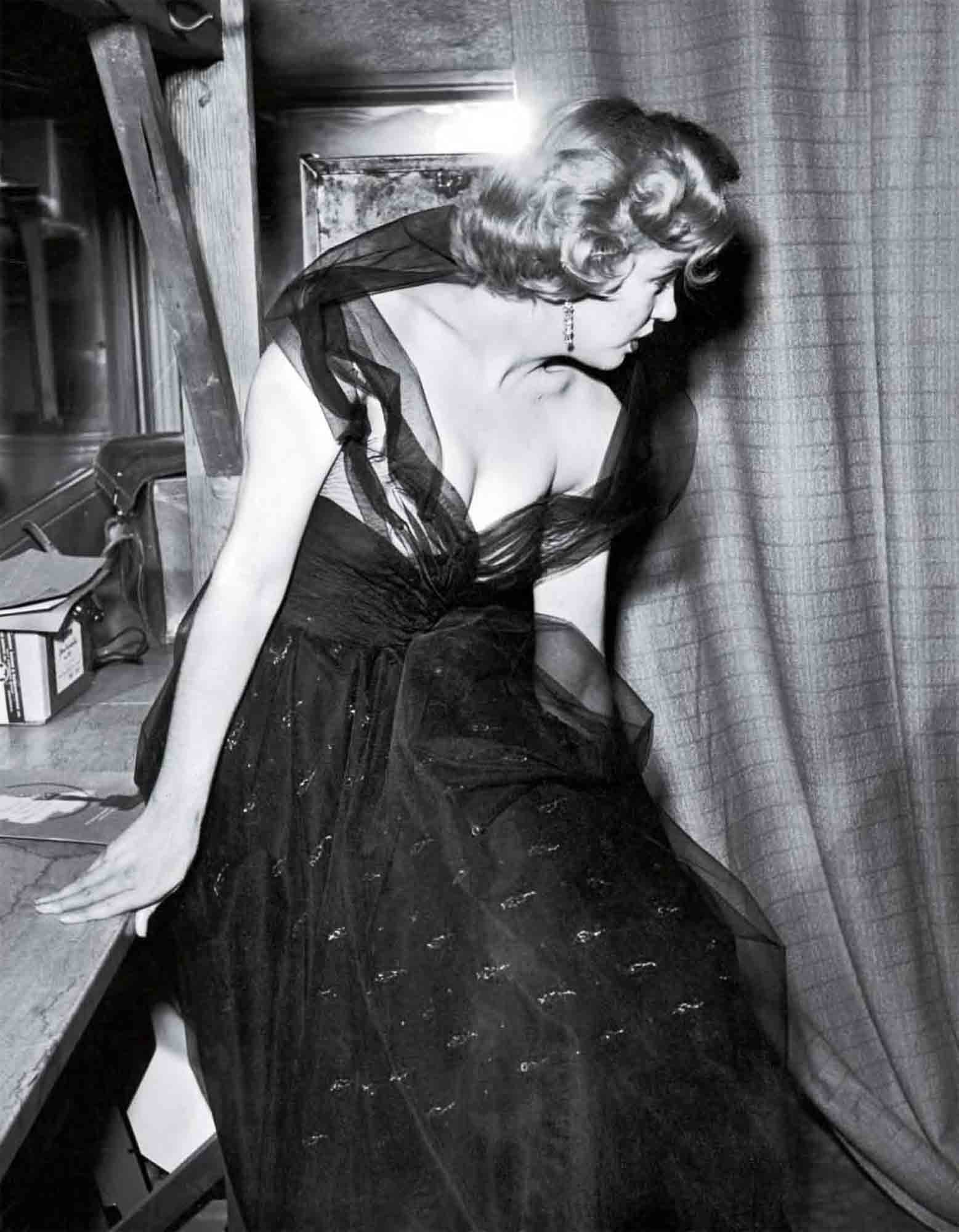

So behind the scenes such events may or may not have taken place, white before the flashbulbs, in the summer of 1953, the actress pressed her hands and high heels into wet cement outside Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, no longer tittle Norma Jeane measuring herself against the imprints of others but Marilyn Monroe, living out the dream.

She clearly knew how large her stardom had become and knew just as weft that she was being underpaid by Fox—for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, she earned a tenth of costar Jane Russell’s take, according to Spoto—and she felt undervalued by the world at large. “I want to grow and develop and play serious dramatic parts,” Monroe told The New York Times in July 1953. “My dramatic coach, Natasha Lytess, tells everybody that I have great soul—but so far nobody’s interested in it. Someday, though, someday.”

Monroe decided to try to take her fate back into her own hands. She had her agent press the studio to negotiate a new contract with better pay and, more important, creative control of her career; she wanted the right to refuse assignments or, at least, to pick some of her on-set collaborators, including directors. Meanwhile, she balked when Fox ordered her in mid- December of 1953 to report to the set of The Girl in Pink Tights, just the kind of movie Monroe was loath to make at that time. She instead jetted off to meet DiMaggio in San Francisco for Christmas. When she failed to report yet again, after the studio had pushed back the start date to early January, Fox suspended her.

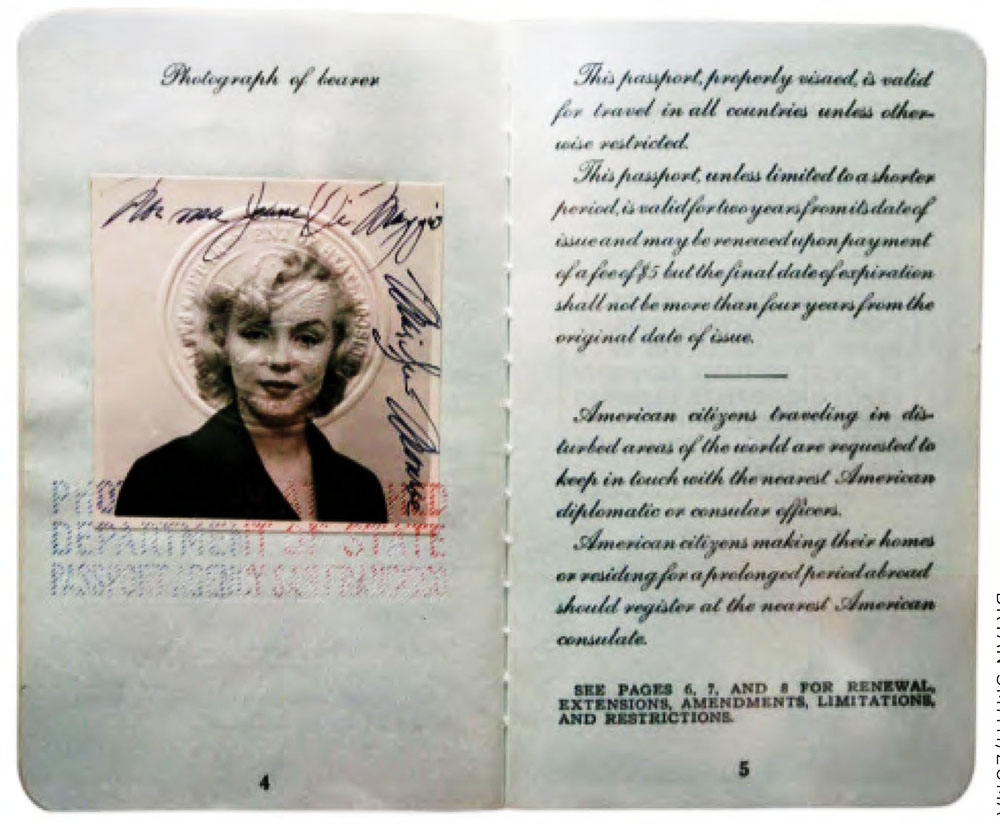

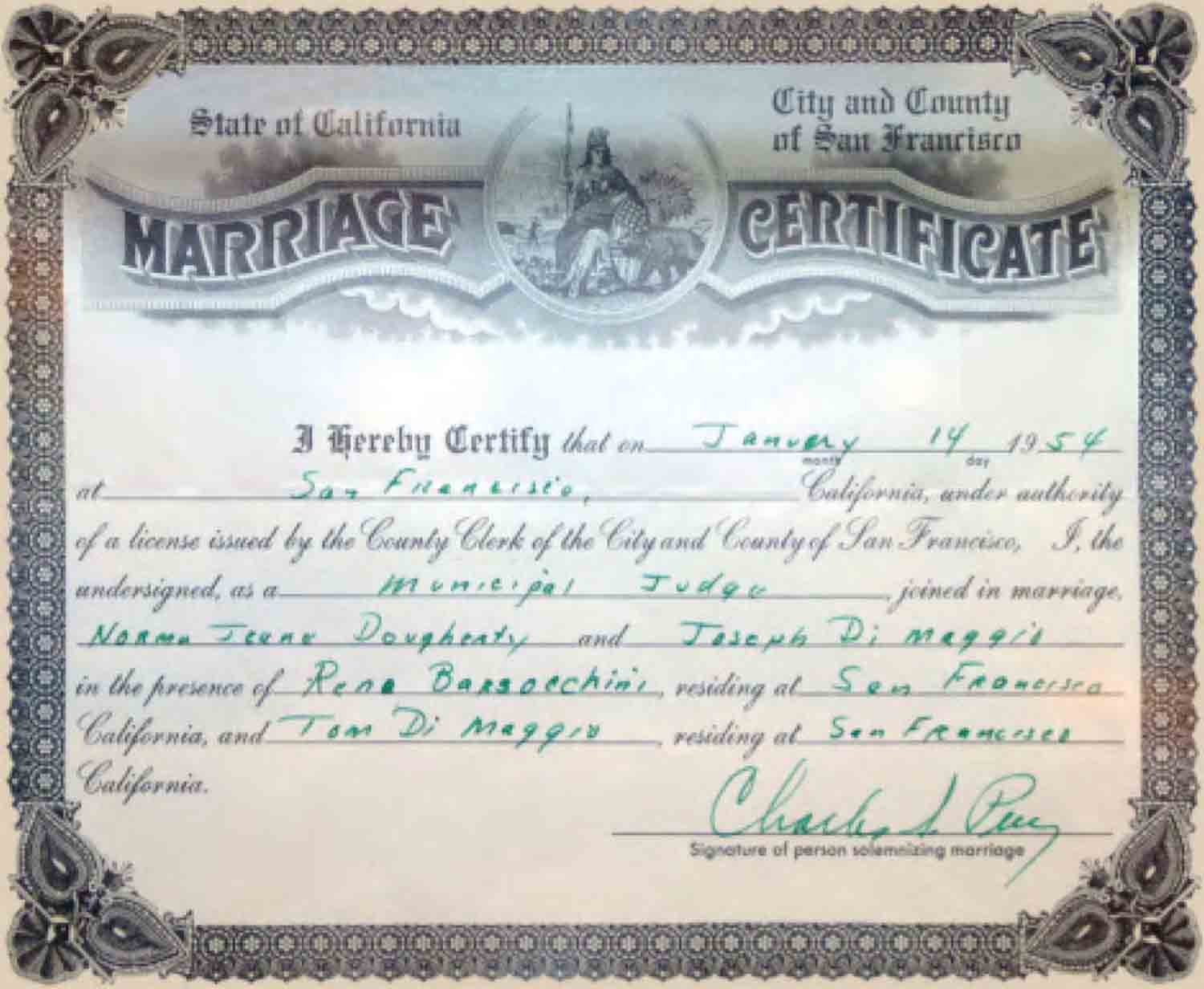

In the midst of all this, DiMaggio proposed marriage, and on January 14, 1954, he and Monroe were wed in a three-minute ceremony at City Flail in San Francisco. According to Spoto, Marilyn turned to Joe at one point and asked if, were she to die before him, he would adorn her grave with flowers each week, as William Powell had done for Jean Harlow. Joe promised her that he would.

The newlyweds flew to Japan, where pandemonium attended their honeymoon as fans craned to see the baseball hero and, as one Japanese radio broadcaster put it, “the honorable buttocks-swinging actress.” The wild attention, abroad as well as at home, coupled with the public’s infatuation with his sexy wife, would very quickly prey upon the private, intensely jealous DiMaggio. Fie had been hoping Monroe would trade stardom for a settled-down life at home—a home that would be far from Hollywood. But her stardom was at its apex while his was in eclipse, and DiMaggio’s desires, it quickly became apparent, would not be fulfilled.

While in Japan, Monroe was offered an opportunity to entertain tens of thousands of American servicemen during a four-day tour of South Korea, and she seized the chance. Throughout her career, she took particular pride in appealing to the everyman—being recognized by a dog walker or a garbage collector—and feeling like she gave their day a boost. She would do the same now for these troops.

And so a bare-shouldered Monroe braved February temperatures to put on a series of honeymoon shows before roaring audiences of salivating American GIs.

“It was so wonderful, Joe,” Monroe reported back excitedly. “You never heard such cheering.”

“Yes,” her husband replied quietly. “I have.”

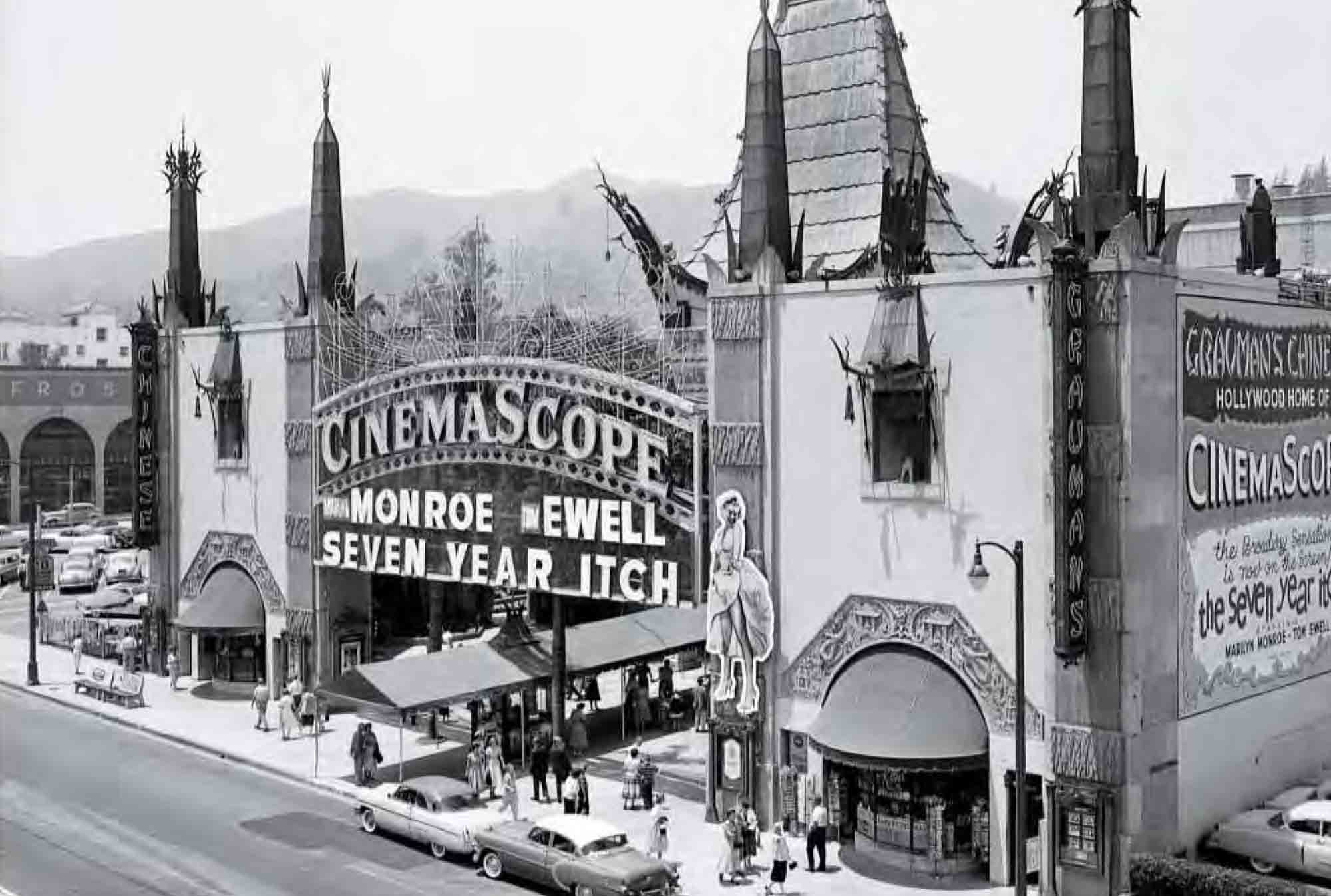

Back in the U.S., Monroe at last returned to work in the spring of ’54. Fox had certainly heard her complaints, was renegotiating her contract and had agreed not to force Pink Tights on her if she instead took a role in the musical There’s No Business Like Show Business. As a plum, she would be given a starring role in director Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch.

Although (and in many ways, because) Monroe’s career was getting back on track, her marriage was quickly eroding. DiMaggio wasn’t enjoying life in L.A.; he would spend much of the day watching TV. He could be withdrawn and distant, and there were times, Monroe later said, when he would go days on end without speaking to her. He also continued to be greatly unnerved by Monroe’s stardom, and there is speculation in some of the biographies that this strong former athlete was violent with her.

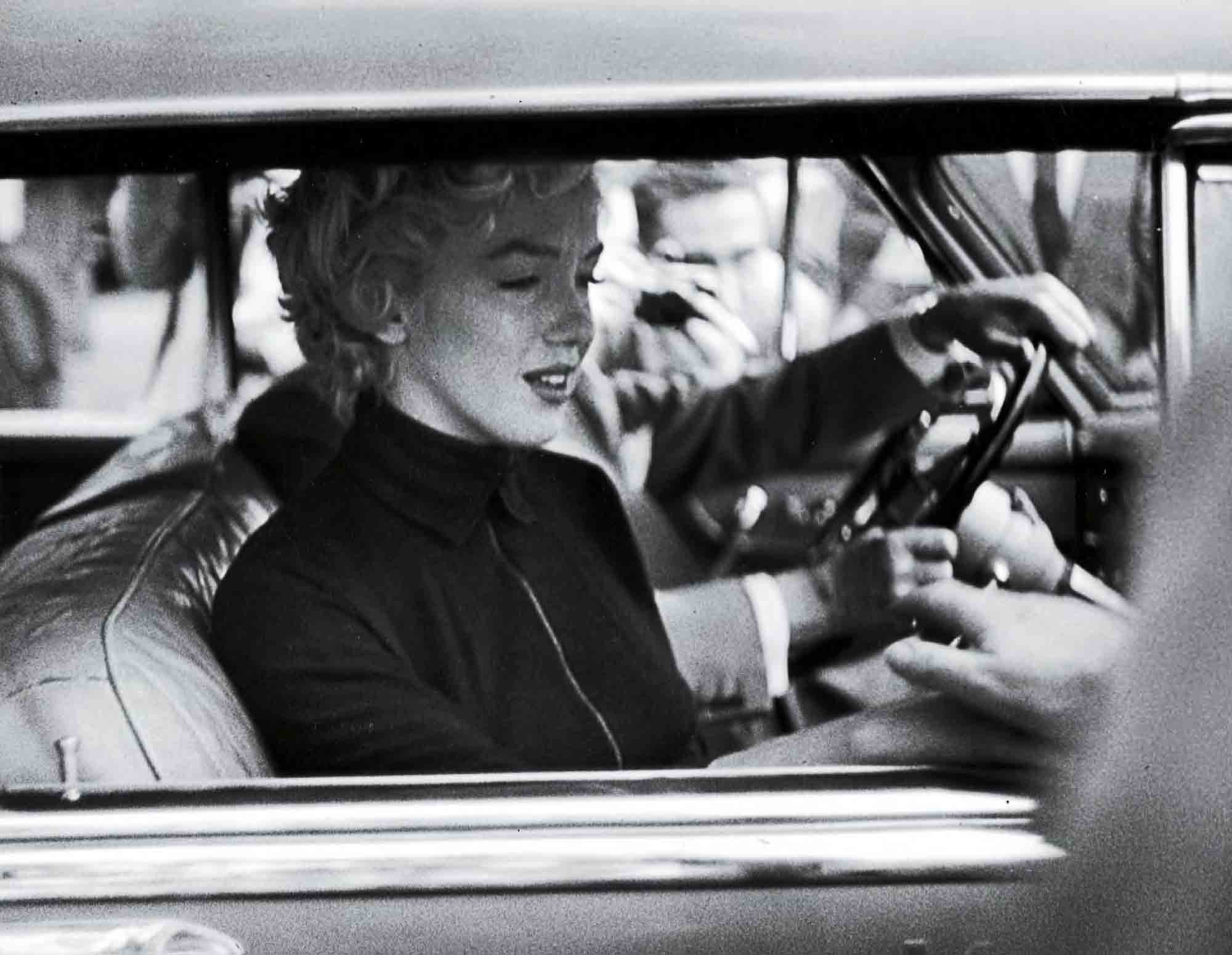

The frayed knot of their marriage finally snapped in mid-September 1954 while Monroe was in New York City to shoot parts of The Seven Year Itch. One of the on-location scenes had Monroe perched over a subway grate as a gust from below lifted her white skirt like a cloud. For hours, a mob of people jammed the city street corner, cheering her on and illuminating the night with a storm of popping flashbulbs. Among the crowd was a furious Joe DiMaggio.

It is widely held that a nasty hotel-room argument ensued, and by some accounts there were bruises on Monroe’s shoulders or back the next day. Whether or not DiMaggio beat her that night, Monroe returned to Los Angeles and, within three weeks, filed for a divorce. At the proceedings, she told the judge that the nine-month marriage had been “mostly one of coldness and indifference.” And with that, it was ended.

A first footnote on the dissolution of this famous relationship: The skirt stunt that finished things off was just that—a stunt. It wasn’t an actual shoot but a publicity gimmick, a way to drum up interest and entice audiences. The footage that actually appeared in the movie was shot later on a soundstage in Hollywood.

And a second footnote: The failure of their brief marriage deeply affected both DiMaggio and Monroe, and although the two were no longer legally bound to each other, they would remain emotionally tied. DiMaggio readily swooped in at a moment’s notice whenever Monroe needed him. He would remain loyal to her in the last years of her brief life—and then after her death.

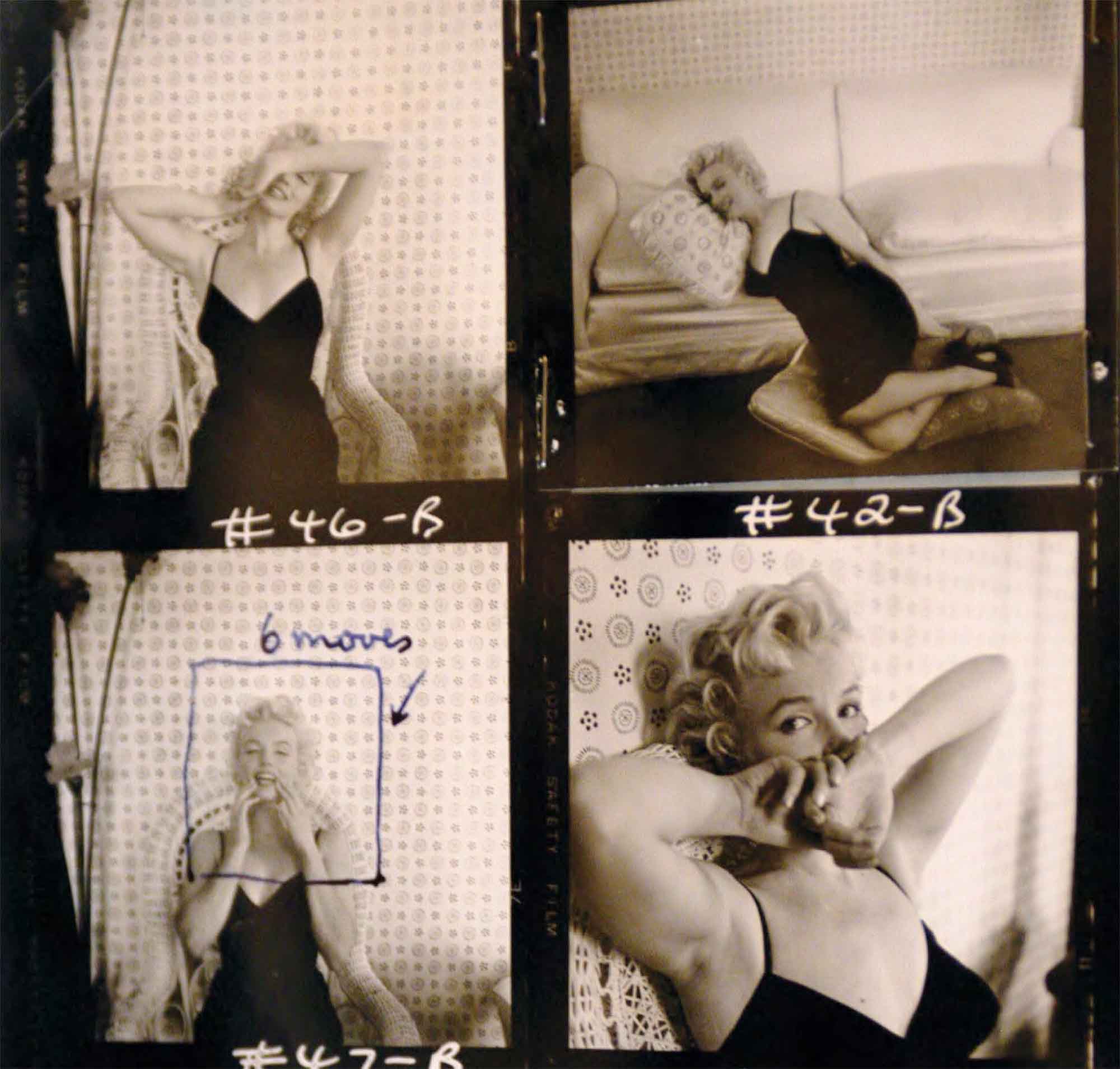

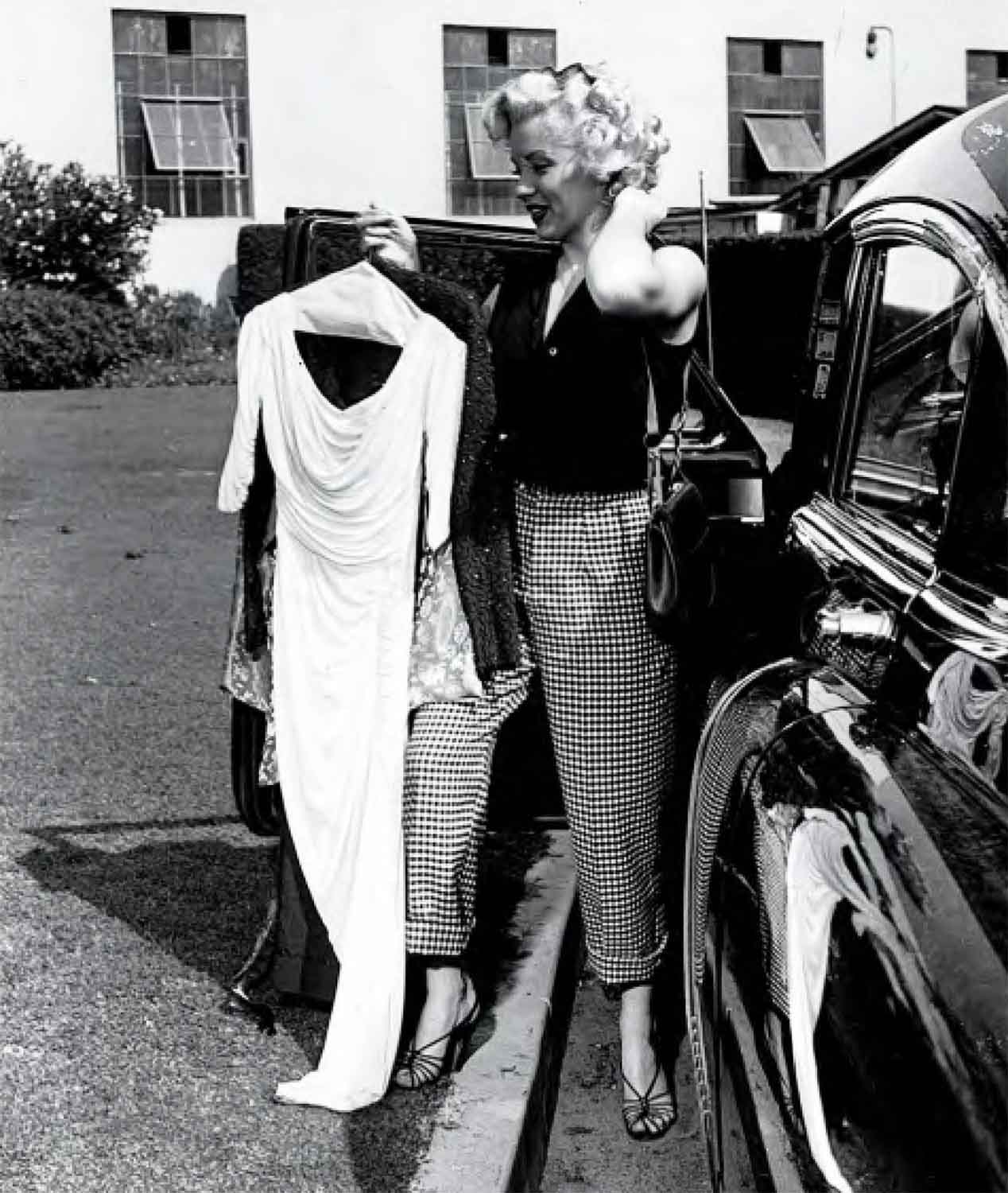

By the end of 1954, it became clear to Monroe that the studio, while making nice, was not going to cede much in the way of creative control. She found a loophole in her contract that under her interpretation freed her from Fox. She left Hollywood for New York City, where she would spend a busy year in an earnest effort to improve her artistry and prove herself worthy of critical acclaim. Meanwhile, in early January of 1955, she and Milton Greene, an A-list photographer who had shot pictures of her in the early days, became friendly. He began advising her on business matters, and soon the actress announced the formation of Marilyn Monroe Productions Inc. She was “tired of the same old sex roles,” Monroe said at the unveiling of her new company. “People have scope, you know.”

Three days after the debut of MMP, Monroe was back in L.A. to put the finishing touches on The Seven Year Itch. “You’re looking good,” Billy Wilder reportedly told her.

“Why shouldn’t I?” she replied. “I’m incorporated!”

The MMP gambit would, Monroe hoped, allow her to leverage her box office performance with the studio; she figured, not incorrectly, that Fox needed her as much as she needed Fox. But more than stardom or money, what Monroe longed for was to be seen as a serious actress; she desperately wanted to be respected. White MMP negotiated a new deaf with Fox, Monroe began acting studies with Lee Strasberg, the artistic director of New York’s esteemed Actors Studio. At Strasberg’s suggestion, she also began seeing a psychotherapist—as often as five times weekly—to enable her to tap into her thick catalog of charged emotions and memories. Strasberg considered such introspection the fuel of Method acting.

She revered Strasberg, and he, his wife, Paula, and their children would become part of a small group that would wield tremendous influence over Monroe in the fast years of her fife. She was like another member of the family, often spending nights in the Strasberg home, and she would hire Paula as her drama coach when she returned to filmmaking in 1956. Paula recognized Monroe’s fortitude and desire to improve, and she supported Monroe’s aspirations. “Marilyn has the fragility of a female but the constitution of an ox,” Paula said. “She is a beautiful hummingbird made of iron.”

On June 1, 1955, Monroe’s 29th birthday, The Seven Year Itch opened and became a huge success, which provided her real clout in the ongoing negotiations with Fox. By year’s end, she had a new seven-year contract that gave her the power to approve scripts and directors for the films she made at the studio, plus compensation of $100,000 per film. Marilyn Monroe Productions, meantime, would be allowed to make movies independent of Fox. In an article titled “The Winner,” Time magazine remarked that despite the snickering that had followed her desertion to New York—she was ridiculed in the press for her association with the Actors Studio and lampooned on Broadway in a comedy about a blonde who feels underappreciated and starts her own production company—Marilyn Monroe “had brought to its knees mighty Twentieth Century-Fox.”

In March 1956, she legally changed her name to Marilyn Monroe. This move is interesting because it is dear from the testimony of friends and associates that she was acutely aware that the Marilyn Monroe perceived by the public was in part a creation, a character, even a caricature. A telling anecdote, as recalled by her friend Truman Capote: One day in 1955, the two of them were leaving a restaurant together. Monroe decided to use the powder room. Capote Later wrote, “I wished I had a book to read: her visits to powder rooms sometimes fasted as tong as an elephant’s pregnancy.” Eventually he decided to check in on her. Knocking, he opened the door to find her before a mirror. “What are you doing?” he asked.

“Looking at Her,” she said.

Other times, she would critique her own scenes with phrases like “No, Monroe wouldn’t do this,” and friends said that she could turn on the Monroe persona on a whim when she felt like attracting a crowd.

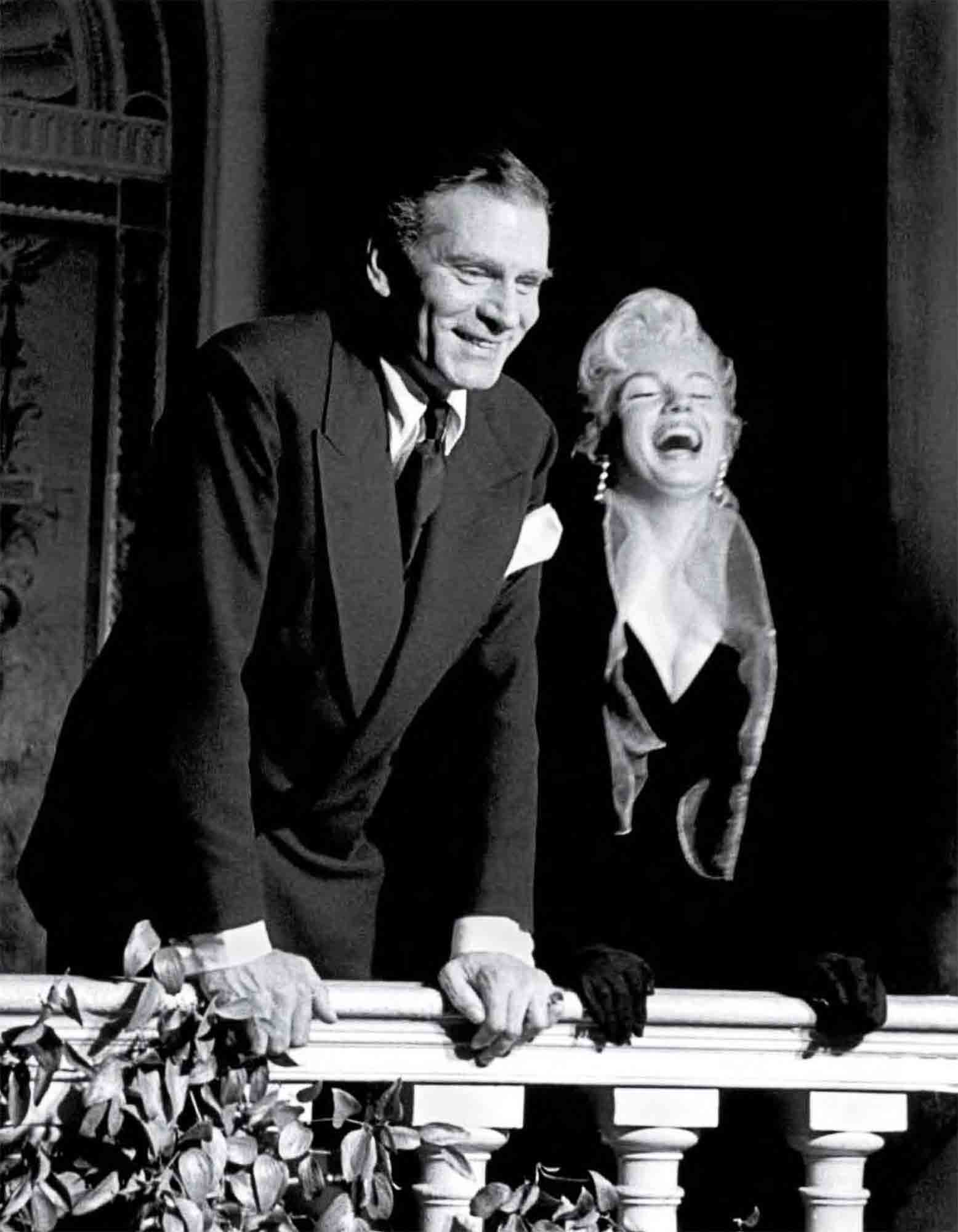

Now she was legally becoming this legendary figure. And it’s evident that she wanted to take firm control of who Marilyn Monroe was; she wanted to reshape Marilyn Monroe. Before returning to Hollywood in 1956 to embark on her next project for Fox, Bus Stop, Monroe laid out p fa ns for the movie that would follow, which would be a major production for MMP. For her costar in that film, The Prince and the Showgirl, she recruited none other than Sir Laurence Olivier. For an actress to play opposite the great Olivier, she believed, weft then . . . that actress would have to be taken seriously. But even at the New York City news conference announcing Olivier’s involvement, she was reminded of how far Marilyn Monroe stiff had to travel. A reporter asked about her designs to play Grushenka in

the The Brothers Karamazov, and she was then asked to spell the character’s name.

“Look it up,” Monroe replied.

She would not have to wait for The Prince and the Showgirl to gain a modicum of critical praise. Although she was often anxious and upset on the set of Bus Stop—her film comeback, after aft, and one in which she would trot out her Method skiffs for the first time—she turned in a winning performance. “Hold onto your chairs, everybody, and get set for a rattling surprise,” read The New York Times review. “Marilyn Monroe has finally proved herself an actress in Bus Stop.”

On top of that, the box office was, again, boffo.

Back in January 1951 in California, Monroe had met and been attracted to Arthur Miller, the playwright who, two years earlier, had won a Pulitzer Prize for Death of a Salesman. In 1955, this time on the East Coast, they reunited and began an affair that would doom Miller’s marriage. “She was a whirling light to me then,” Miller would later write, “all paradox and enticing mystery, street-tough one moment, then lifted by a lyrical and poetic sensitivity that few retain past early adolescence.”

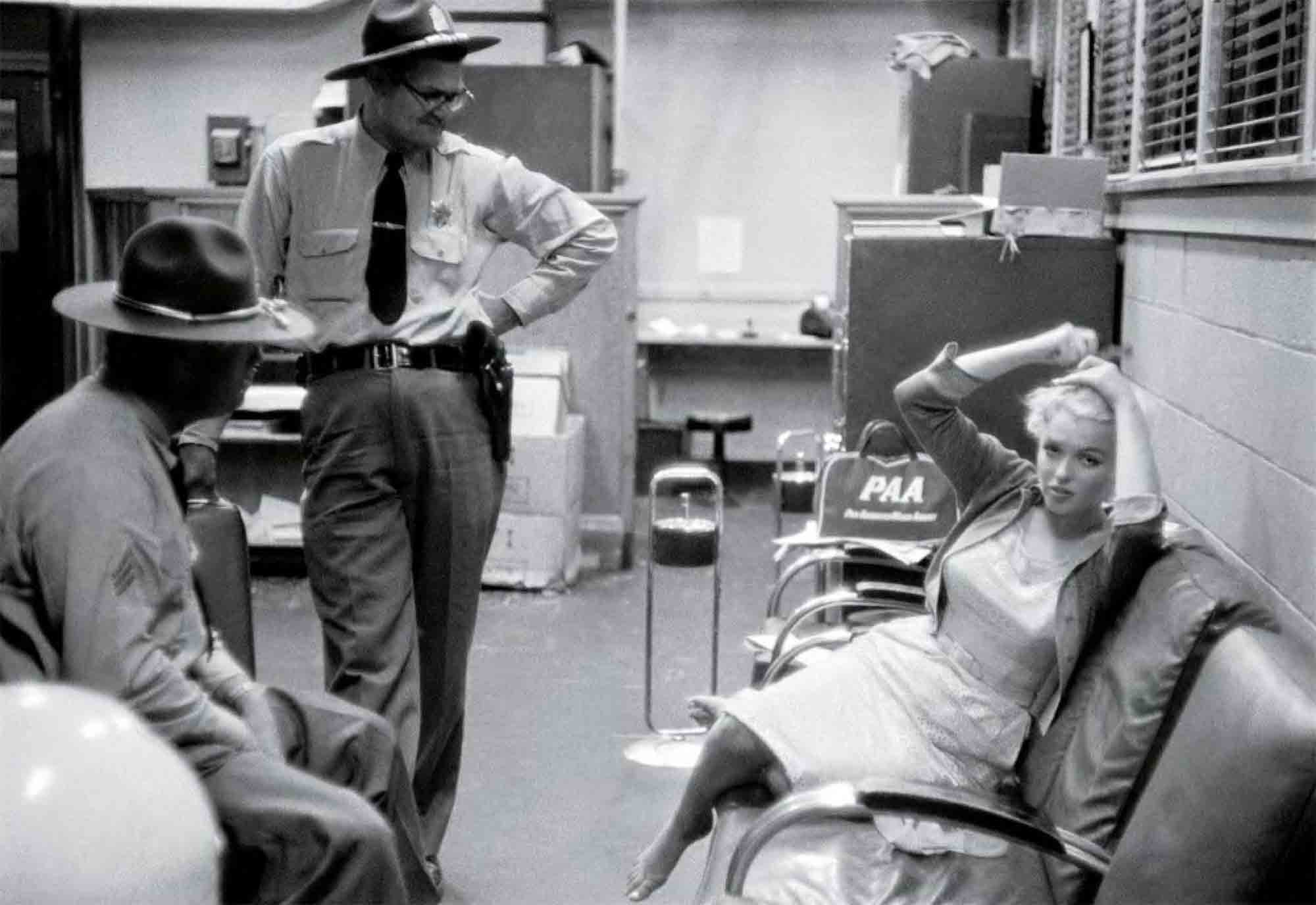

After Miller was divorced from his wife, Mary, in 1956, he applied for a passport renewal so that he could travel to London; he planned to be there for a production of one of his plays and to accompany Monroe as she worked on The Prince and the Showgirl. But suddenly, he was summoned to testify in Congress before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which said it was looking into passport fraud.

For more than a year, Miller had been at-trading the scrutiny of the committee, which had, as one focus, the goat of rooting out any Communist infiltration of the entertainment industry. In 1953, Miller’s heralded play The Crucible had made a metaphorical fink between the work of HUAC and the Salem witch hunt trials of America’s Colonial era. Whether the play contributed to Miller’s being catted to Washington has never been proved but always supposed.

Miller, well aware of which way the wind was blowing, told the committee in advance of the passport-fraud hearing that if he were pressed to name names of any associates who might have Communist sympathies, he would refuse to do so. And so he entered the room.

Warned that she was putting her popularity in jeopardy, Monroe nevertheless was steadfast in her support of Miller. As might have been expected, the committee demanded that Miller tell all that he knew—not about passports but Commies. He responded: “I could not use the name of another person and bring trouble on him.” Miller would subsequently be cited and convicted for contempt of Congress, a ruling that would be reversed on appeal in 1958.

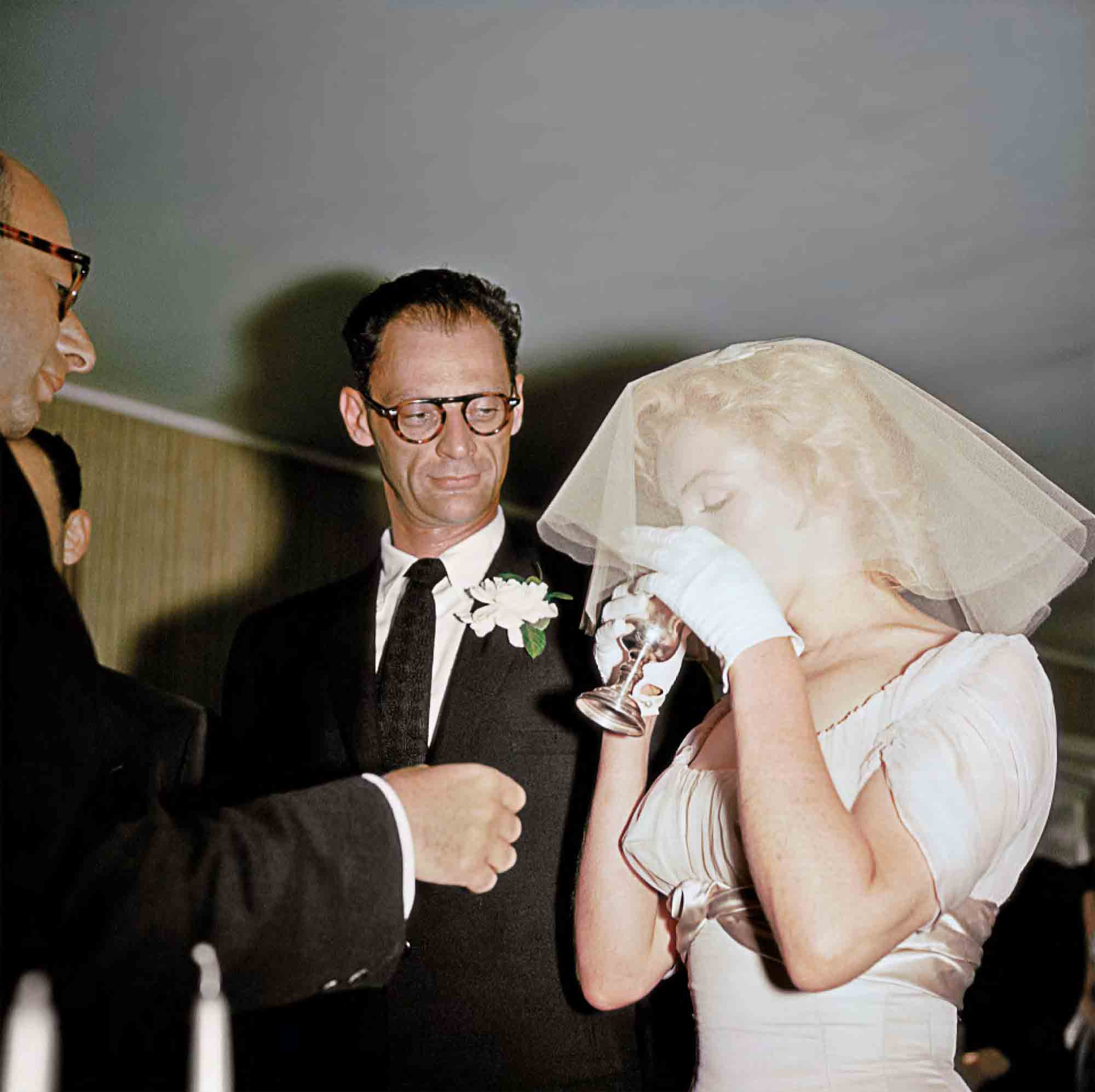

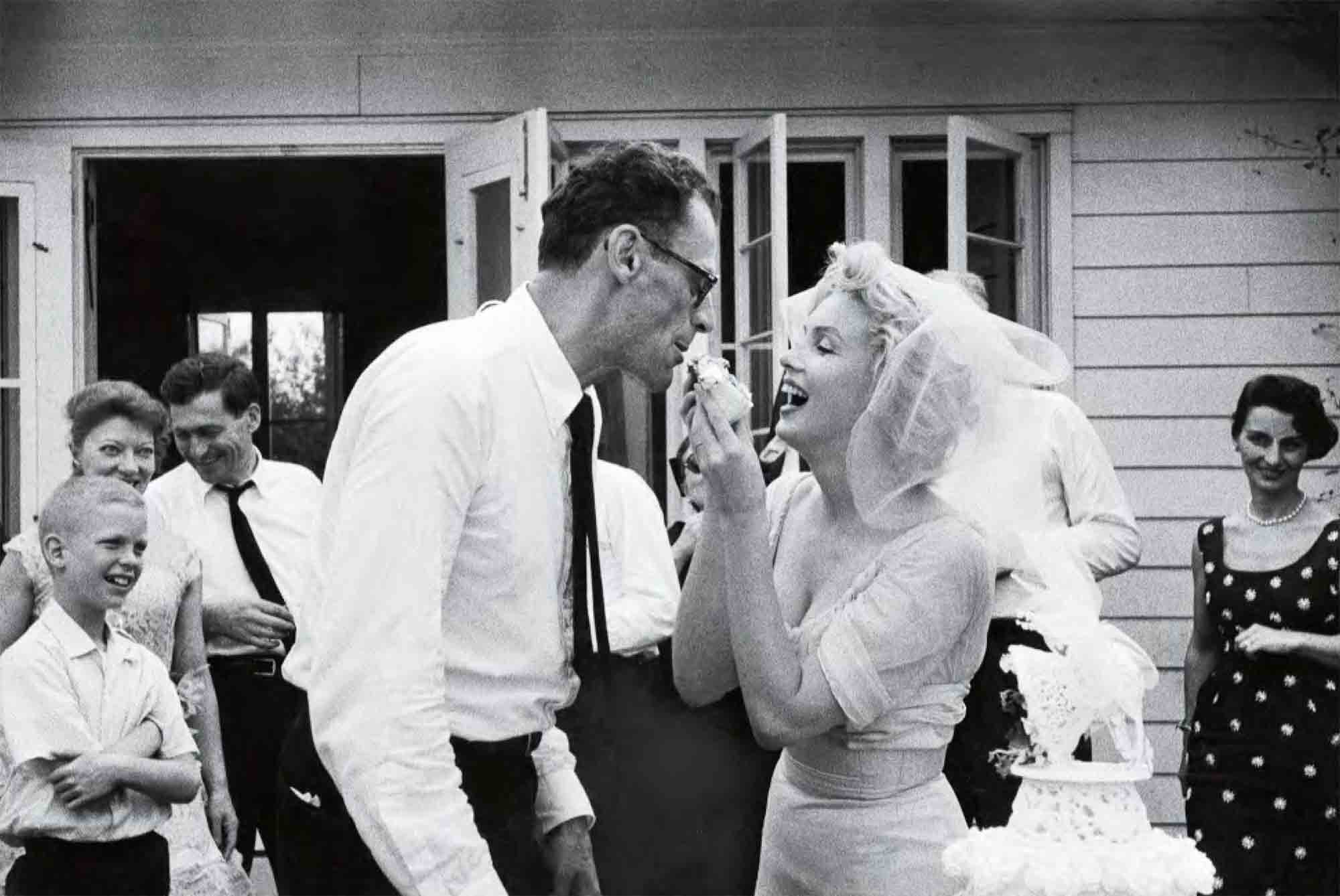

But in the midst of the turmoil in Washington, before any citations had been handed down, Miller announced something that was even more consequential than Communists were to a certain sector of America: He said that he planned to marry Marilyn Monroe in a matter of days. It was an unconventional proposal to say the least, but the lady said yes.

They were wed, first in a civil ceremony on June 29, 1956, and then again two days later in a Jewish ceremony before a small group of guests.

A headline in Variety captured the prevailing view marvelously: EGGHEAD WEDS HOURGLASS.

It is a quote. LIFE MAGAZINE JULY 2017