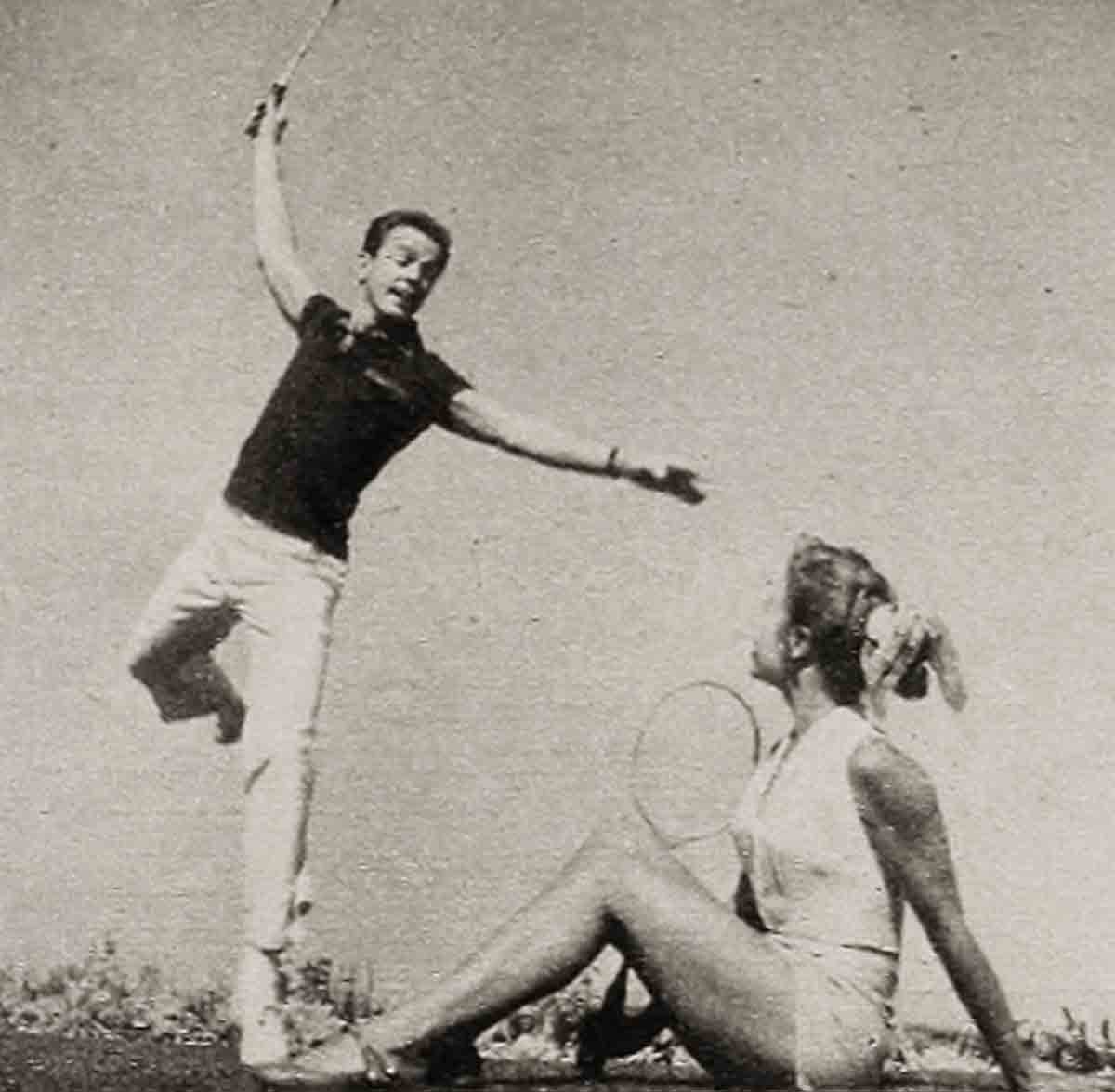

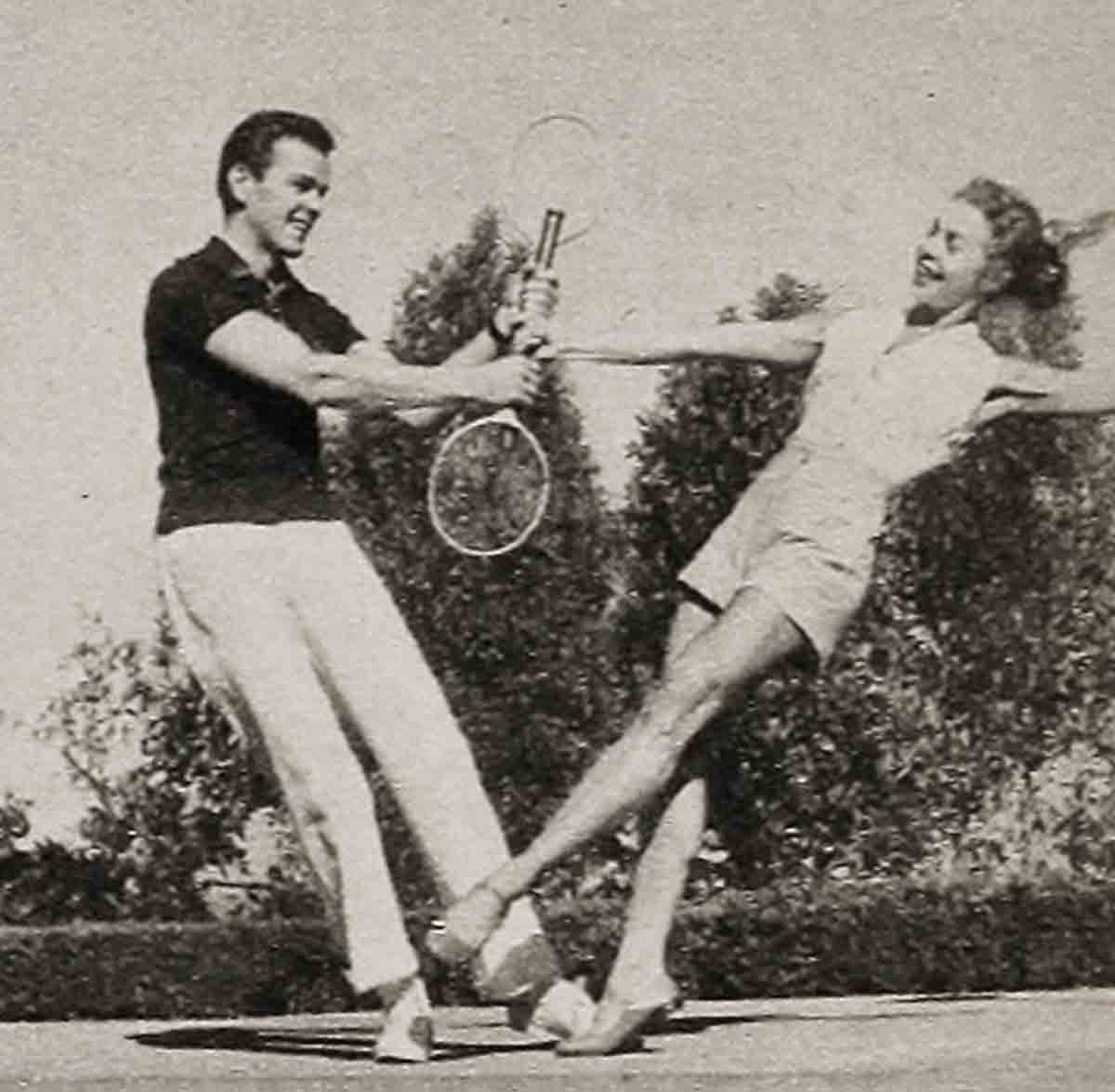

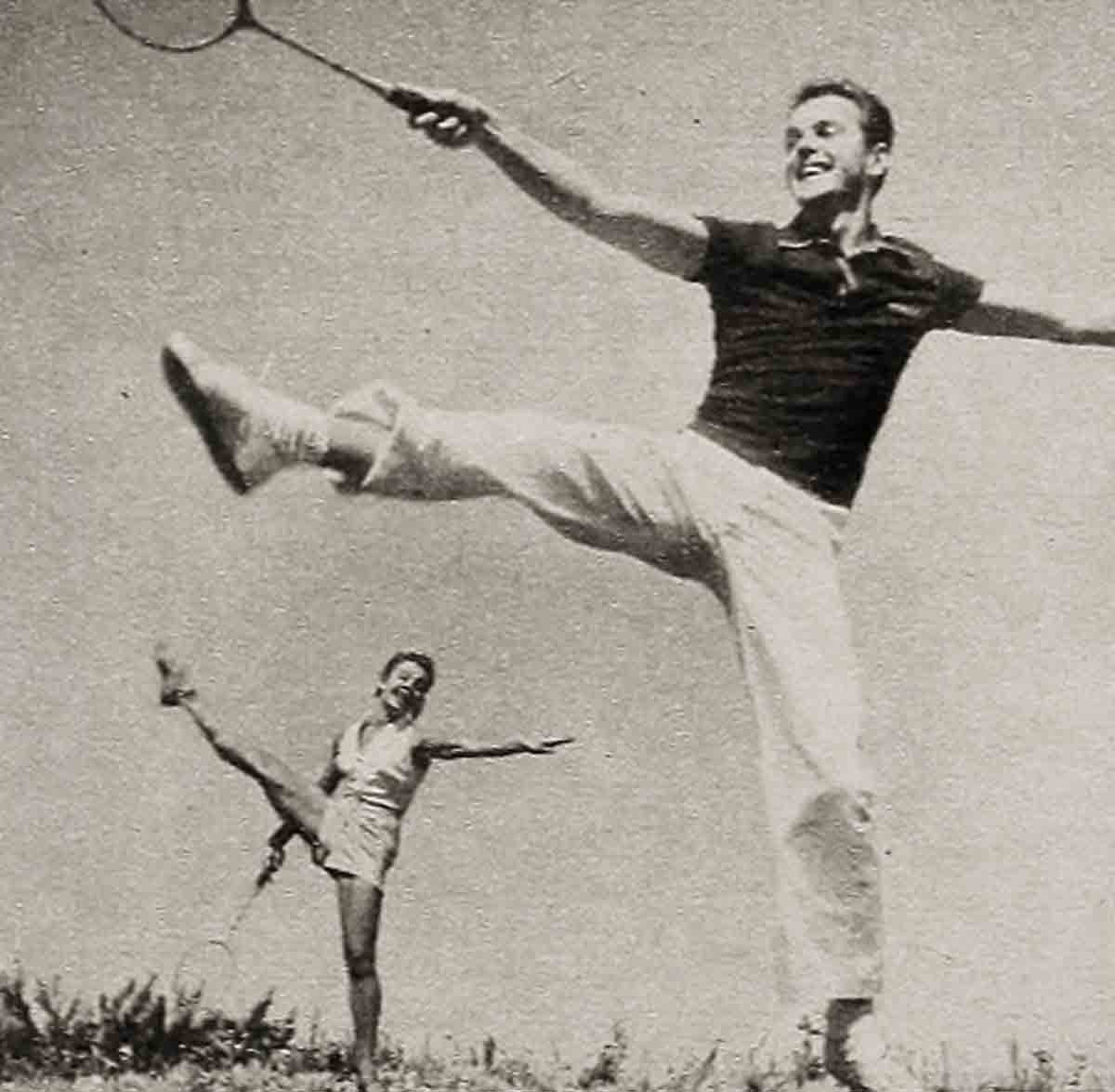

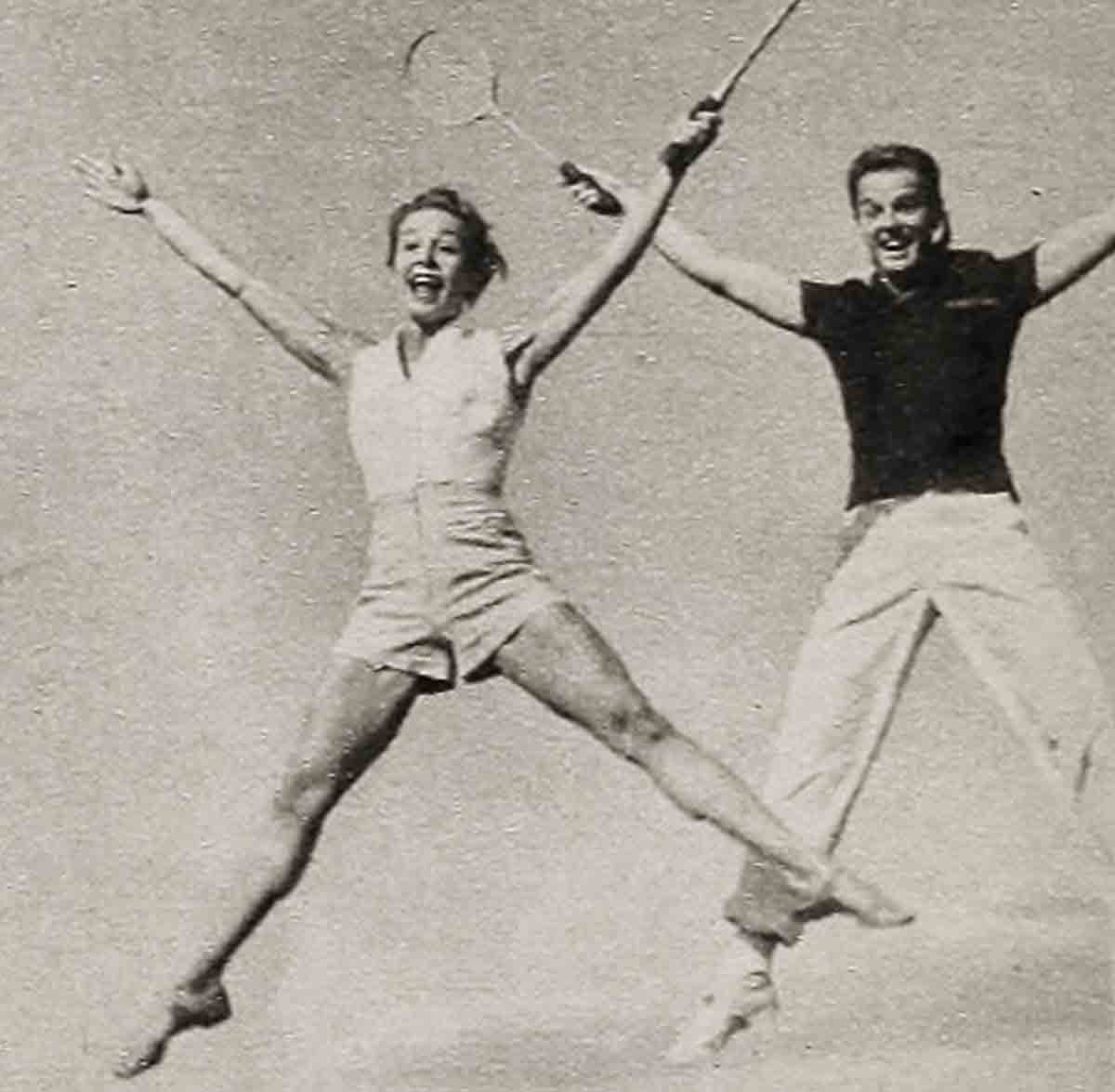

Perfect Balance—Gower and Marge Champion

To the sleepy gas station attendant, the slim figure rapping at his glass door looked like some little girl lost. It was plenty past midnight in Hollywood and he’d seen her scurry across Sunset Boulevard from the darkened front of Schwab’s Drug Store. Her round, brown eyes under the blonde, bun-tucked hair looked anxiously troubled, and he thought, “Some dame who got ditched by her date after a hassle.”

So when she said, “May I use your telephone?” he just grunted, “Help yourself,” and went back to the race track results. But he looked up again when she told the operator, “New York, please,” and started feeding half-dollars into the slot as if it were a Las Vegas one-arm bandit.

You couldn’t blame him for eavesdropping a bit after that but he didn’t hear much. Just this girl telling some Joe across the country, that she loved him and couldn’t sleep until she heard his voice. He didn’t know that for this soothing assurance, Marge Champion had rolled down from the top of the mountain and her lonely house, which didn’t have a telephone then, to haunt Schwabs’ booths for three hours until they swept her out, trying to talk a’ Manhattan hotel into violating “Do Not Disturb” instructions. He didn’t know how important it was to her just to hear a tall, boyish-looking and undeniably drowsy. fellow say the words she had to hear. But then, of course, he didn’t know Marge and Gower Champion.

Since Gower had gone to New York, everything had gone wrong. First, the plumbing at their house had burst in the middle of the night. In the studio, three feet of water had poured onto the expensive cork dance floor they’d laboriously sanded to just the right slipper touch. It took Marge, two patrol cops and assorted friends until dawn, bailing and swabbing in hip boots, to save the place. Then a windstorm had whipped up, sending the spare shutters Gow had stacked whistling around the place like boomerrangs. After that, a tipsy milkman whirled into the drive and knocked over part of a brick wall and three prize camellias. Two cherished cats had vanished and, just to wrap things up dandy, a cop had ticketed Marge that morning for crossing a white line!

Of course, Marge hadn’t let “the Boss” in on the bad news that night—he had the choreography of a Broadway show on his mind. But just saying hello made things better. And he would soon be home. She gunned her roadster back up the hill and flopped into bed.

Luckily, the absent lover blues have seldom seized Marge Champion in her half dozen years of marriage. Marge and Gower have been as inseparable as shadows—walking, eating, working, playing, sleeping.

A few days before last October 5, the graceful, crewcut stringbean Marge Champion loves pulled the gold engagement ring off his dainty wife’s finger and took it down to Tobias, the Beverly Hills jeweler. This year the diamond he added to the glittering arc of five is the brightest of all to Marge and Gower—and with good reason.

When he bought that ring, Gower Champion had to scrape the pockets of his lone tuxedo to do it. The Champs were a struggling dance team then, chronically in hock for Marge’s gowns, fighting to pay the rent on a basement apartment. They had prospects, it’s true, but few dance dates.

Now things are different. As anyone knows, the Champions are the most popular, highest-paid dance duo in America, Since they dazzled Hollywood four years ago with their fairyfooted, romantic grace, they’ve been the highspots of such picture hits as Mr. Music, Showboat, Lovely To Look At, Everything I Have Is Yours and Give A Girl A Break. They’ve also been, and still are, record smashers at the best hotels and nightclubs all over the land and on TV, too. Last year they collected $130,000 and many awards for this and that. They’ve got what both have always wanted—a big time career.

The grey house with the black shutters tucked into a Hollywood hillside is also what they’ve both always dreamed about. And the two barrels of knickknacks, the Lautrec poster and the unpaid-for piano with which they started housekeeping are surrounded by rich (and paid for) antique and modern furnishings, good prints and sketches, shelves of books, racks of records—all the things that make a house the kind of home both Champions love. They’ve got relatives all around them, friends galore, five spoiled cats, and two white cars in their garage. But most of all, they’ve got each other, and a marriage that grows richer and firmer every hour. And that, considering Marge and Gower Champion’s Siamese twin setup, is the most amazing accomplishment of all.

Now, ideally the ancient rites of marriage should result in a perfect blending. But in practice, many brides and grooms who have shaken the rice out of their hair will attest that it is nothing of the sort, although it is true that sometimes they get to looking like each other even by the tin anniversary. They talk alike. A sort of mental telepathy develops so that they think the same things at the same time. That’s evident in the Champions’ dancing which, as one critic marveled, “seems as if they had radar in every muscle.” For example, Marge tripped, making an entrance, and fell on her face. Behind her, Gow immediately made the same stumble and flopped the same way.

When they played the Statler hotel in Cleveland, Marge got woozy with a fever. The doctor came and gave her sulfa. Next day she was all over red spots. “Measles,” he said. So they slapped her into the contagion ward of the City Hospital with barely time to tell Gow goodbye, and no way of communicating with him—no phone, not even notes that might carry germs. A City doctor took over, and for a couple of.days Marge might as well have been in jail.

The place was. swarming with speckled kids. One of them peeped at her and blurted, “You don’t have measles—you don’t have measle eyes.” Marge began to wonder. That noon, her original doctor came in. “I’m not supposed to be here,” he said, “but your husband keeps insisting you don’t have measles. To keep him quiet, I came over.” Well, she didn’t have measles. Just flu and a sulfa reaction. But how did Gow ever know that, with Marge incommunicado?

That phenomenon is sometimes weird, but it’s also fairly common with any Mr. and Mrs. What’s remarkable in the Champions’ ease is that the side-by-side, round-the-clock, foot-away life they lead, constantly under the nervous tension of creating, pressed by deadlines, exhausted by physical exertion, remains a lovebird affair. As a good pal of theirs, a star whose home broke under similar Hollywood strains marvels, “By now, those kids should be sick of each other, but they get sick without each other. The way they live they should be throwing rocks. Instead, they throw kisses. How do they do it?”

Marge and Gower Champion are very different. The Midget has a personality as open and airy as a barn door. Gower keeps his corked up like a bottle of champagne; when he pops it, the boy can bubble in sparkling style, but usually he’s standoffish, even shy. As a new acquaintance put it a little bitingly, “Somebody left the ‘I’ out of Gower’s name.” Another long-time friend, warm, demonstrative Nanette Fabray, always used to greet Gow with a hug and a smack until Marge took her aside one day. “Nanny,” she said, “if you don’t mind, please don’t swarm over Gower like that. If makes him miserable.” Yet, Marge is inclined to do the same thing to her friends’ husbands, or to practically anybody she’s fond of.

Marge’s piano smile is easily her best feature. Often you wouldn’t know Gower had teeth. He’s a worrier, she seldom creases a wrinkle. He’s the grand sweep boy; Marge ties the ideas down. Gow writes and Marge edits. In most other ways you stack them up they’re different. Marge is a gourmet; food is just food to Gow. She has to watch stuffing; he has to be coaxed to eat. Marge will have a drink or two; her husband doesn’t touch the stuff. He likes to get up early; she clings to the hay. In money matters he is extravagant and Marge makes like a Scotch housewife. Gow will shoot the roll on a canvas while Marge argues with a housepainter over how much thinner to use. And so it goes up and down the line—big things, little things—they’re no double exposure. But this, some people think, is exactly what keeps their sandwich style married life from going stale.

“You see,” explains the same Nanette Fabray, “Marge and Gow don’t blend at all—they balance. What Marge lacks, Gower has; what he’s missing, she makes up. They need each other every hour. It’s as simple as that.”

Another factor, as Miriam Nelson (Gene’s estranged wife) points out rather wistfully, “is a little item called love.” Stanley Roberts, a screen writer, once observed, “When Marge looks at Gower her eyes tell him he’s the most important person who ever lived—and to her he is.” Experts agree that even in their dancing Gow’s “I-could-eat-you-alive” look is a big reason why both sexes, from sixteen ta sixty, get mushy inside and stay breathless when they float out on a stage. A huddle of terpsichore critics, analyzing their success, explored every egg-headed angle of technique, training, art and what-all. Finally one blurted, “You can plant me in rows for a corn crop, maybe—but in my book, the extra factor that makes them great is this: You can tell they’re so damned much in love!”

When you look beyond moonlight and roses for the ties that bind the Champion marriage, they aren’t hard to find.

One of the strongest, of course, is the mutual life’s work. It throws Marge and Gower together in what could be explosive proximity. Like the husband and wife who run a chinchilla farm together, they both work every day toward the same goal. They worked toward it separately, as kids, before either looked sidewise at the other.

To say that dancing is the mutual driving force of Mr. and Mrs. Champions’ lives is an understatement. They never get away from it and never really want to. Of course, what Marge gets asked, ad infinitum, is, “Do you ever have any fun just going out dancing?” Her answer is always, “Of course. If we don’t have to perform.” Nowadays, what the Champs call “Arthur Murray dancing” is for them, curiously, a rare treat. Not long ago they decided, sentimentally, to step out to the Del Mar Club at the Beach. As teenagers, they had gone on dates there.

But after just one dreamy waltz, sure bandleader spotted them, stepped to the mike and—there went the romantic evening. They were on exhibit. That happens all the time. They’re glad it does, of course, but admittedly it’s one of the things that keeps them at home, or sends them scurrying back early. “At midnight,” laughs Miriam Nelson, “Gower and Marge turn into pumpkins.” But there’s a bigger reason for that. Their home is another powerful binder for their marriage. Both Marge and Gower fervently appreciate it.

For one thing, neither of them ever really had a home until they had this one together. Gower was a divorce orphan from the age of three, brought up by his mother. Marge had the same story, only it was her father who brought her up. In both cases, the job, though done singly, was done well. Still, it wasn’t what the rest of the kids had. Now, a couple of families have, in effect, joined up.

All this is more than either Marge or Gower Champion dared dream about when they first teamed up to dance. Their love story started when both were junior high adolescents, but between that groping time and their marriage they both collected some beautiful bruises going through separate mills.

While she was still in her teens, Marge had the shattering experience of a broken marriage. Gower racketed around, too, with disappointing attachments. Both tackled New York alone and when they met again they finally knew what they wanted—each other. They didn’t launch their lives together with champagne, nor even beer. When they were married six months after their first dance engagement, they couldn’t afford a honeymoon.

Marge still can’t stand the taste of boiled eggs, because in those newlywed years she bubbled so many over a hot plate in their hotel rooms. There’s a battered portable refrigerator in their studio today that helped keep them alive on the road when they couldn’t afford to buy a meal where they danced.

But if Marge and Gower Champion were sometimes short of cash, they’ve never been short of love and courage. It took a helping of moxie, in the first place, for Marge to ditch the best chance she’d ever had at Broadway fame, when she passed up the lead in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Allegro to join Gower chasing their rainbow. Later, it took some more to leave the east, where they’d made a name, and take on Hollywood. That shrewd show business queen, Sophie Tucker, for instance, told them they were crazy to come to Mocambo in Hollywood. “You’ll die on that small floor with that tough audience,” she predicted. “But,” she sighed, “you’re both young and you’ll bounce back.”

As everyone knows, at Mocambo the Champs bounced not back but ahead—right into pictures. And on the first Hollywood hop they bought the house where they live. They couldn’t afford that then, either; the price was as steep as the hillside it clung to. But they know it’s been worth every penny they mortgaged themselves for—not only as the security anchor both Marge and Gower craved, but also as the escape valve for their high pressure two-career marriage.

Marge has a deep affection for flowers. She still keeps three pressed roses which Anna Pavlova gave her the first time they met. That was following a performance, during which the ballerina slipped to the floor in a rare fluff of her art. Afterwards, taken to her dressing room by her dad, Marge noticed roses scattered helter skelter in a corner. Although at that point Pavlova rated with her like Babe Ruth would rate with a boy, Marge, five, indignantly spoke her piece.

“You oughtn’t to throw roses like that,” she lectured. “They can’t help it if you fell down!” The dancer laughed, promised never to mistreat flowers again, and gave her the three posies.

Gower is not so romantic about flowers, but just as artistic outdoors as he is in. As in his dance numbers; he does the spade work, lays out the plots and manages a ballet effect, sometimes with the strangest things. Last spring they set out some deep blue delphinium. That called for a color contrast, Gow felt, so he backed it with a hedge of rhubarb. In front, he planted parsley. And on a bare slope that threatened to run mud with the rains, he dotted artichokes. It looks surprisingly good, and tastes good, too.

Once you penetrate the Champion jungle and step inside the house, there’s evidence all around of Marge and Gower’s relaxing outlets at home. Marge, by now, is a cook supreme. As for Gower, he’s eternally got some Rube: Goldberg device underway. The latest is a dumb-waiter to their pool, four flights down the hill from the kitchen. He overlooked the small matter of motive power, so you have to haul it up and down by hand, but he thinks it’s wonderful. Sensitive to noise, he’s got all the phones artfully padded with some sort of fluff so, as Dick Pribor, their accompanist, says, “they don’t ring—they purr.”

The Champs have flocks of friends in all sets and circles and by now about everywhere you can name. In Hollywood, their house, which has Victorian ice cream parlor chairs in the kitchen, antique bird cages in the front room, modern paintings on the wall and functional pieces under Gay Nineties fixtures still blend in what they call “modern-baroque” for a colorful, cozy effect. As Lisa Kirk has noted, “Marge and Gower’s house says, ‘Come in’ and after that, ‘Be yourself’.” And that’s a compliment.

Their friends do come in, constantly and endlessly, despite the Alpine climb. The favorite open house is Sunday around the kidney shaped pool when Marge whips out the herbs and prepares her famous ‘California hamburgers.’ Regulars include Lisa Kirk and her husband, Bob Wells, Paula Stone and Mike Sloane, Nanette, Miriam Nelson, Tony Curtis and Janet

Leigh, John and Jeanne Champion, Marge’s brother, Dick, and family, Dick Pribor—and of course the five haughty pussy-cats—Clarabow, Flowerpot, Muggins, Lester and Albert.

In their friendships, neither Marge nor Gower are passive. Their outgoing natures, one demonstrative, the other reserved, seem to be equally spontaneous and sincere. Almost everyone they know can come up with a story wherein the Champs have been actively friends in need.

Nanette Fabray moved into her new house last spring, and got the flu on moving day, a dismal ordeal anyway. But Nan is a lone divorcée, and she couldn’t have been more depressed, with everything piled in a mess and her temperature up to 102. Although they were busy getting together new dances for their last tour, Gower and Marge rattled right over, shifted all the furniture into place, screwed in the light bulbs, hooked up this and that, hung pictures and cooked her dinner, too.

People are so used to seeing the Champions a deux that when either shows up publicly without the other, it’s a natural gossip item.

Last time, that happened after one of those Sunday night parties when the Nelsons, Nanette, Lisa Kirk, Curtis, Leigh and company wanted to go on to Mocambo. Gow shook his head because he had a dance idea on his mind and wanted to block it out at the crack of dawn on Monday. But Marge got talked into going on alone. “You’ll be sorry,” kidded her boss. She was. That brief exposure without Gower made the room buzz and next morning the columns had question marks after their names.

It will take mightier crowbars than those to pry the Champions apart. After six solid years, they’re still happy with each other, although they are together every hour. That could be because, as one critic recently observed, “They dance, not from their feet up, but from their heads down.” It could also be because they keep dancing from their hearts out.

THE END

—BY JACK WADE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1953