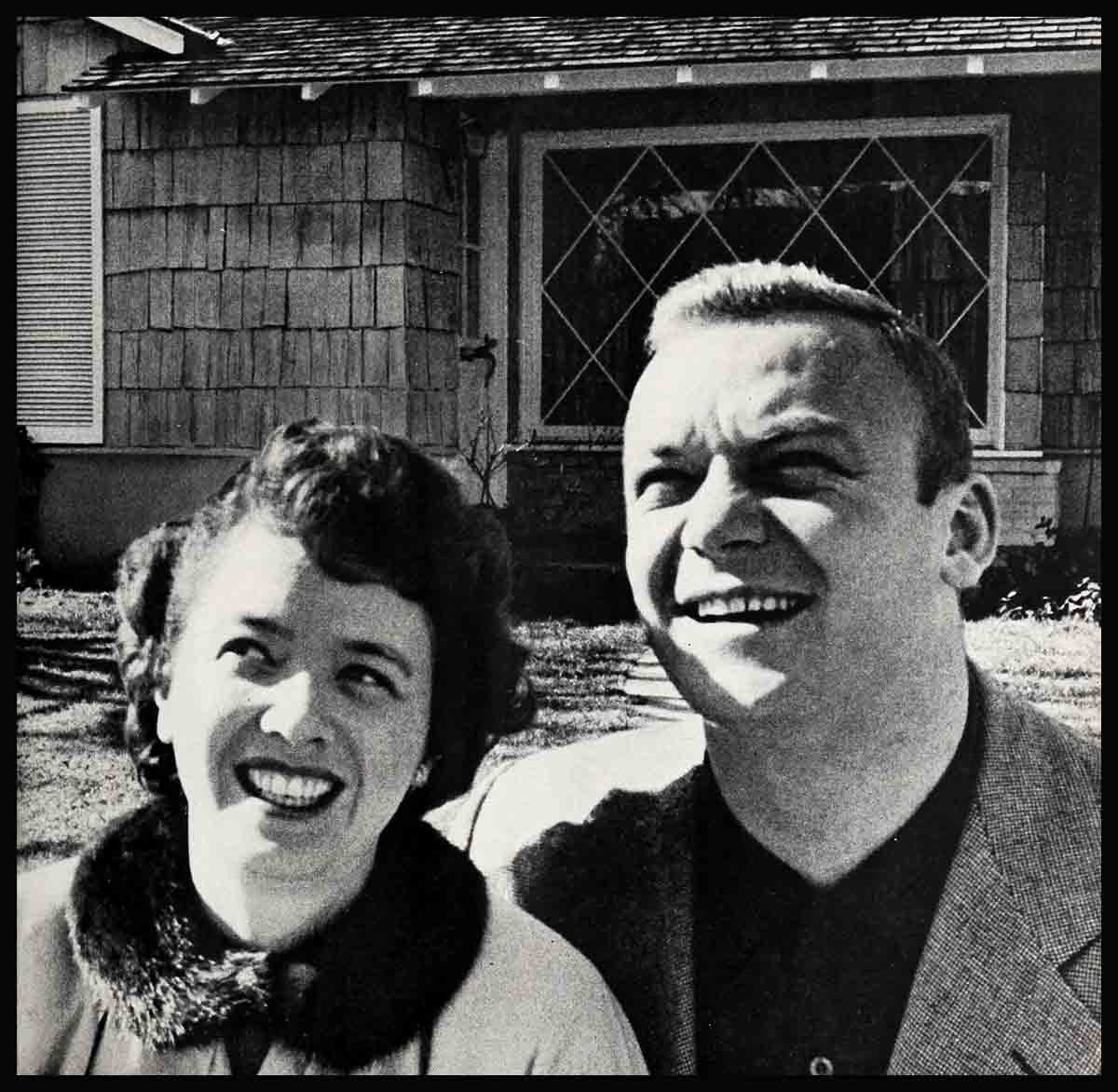

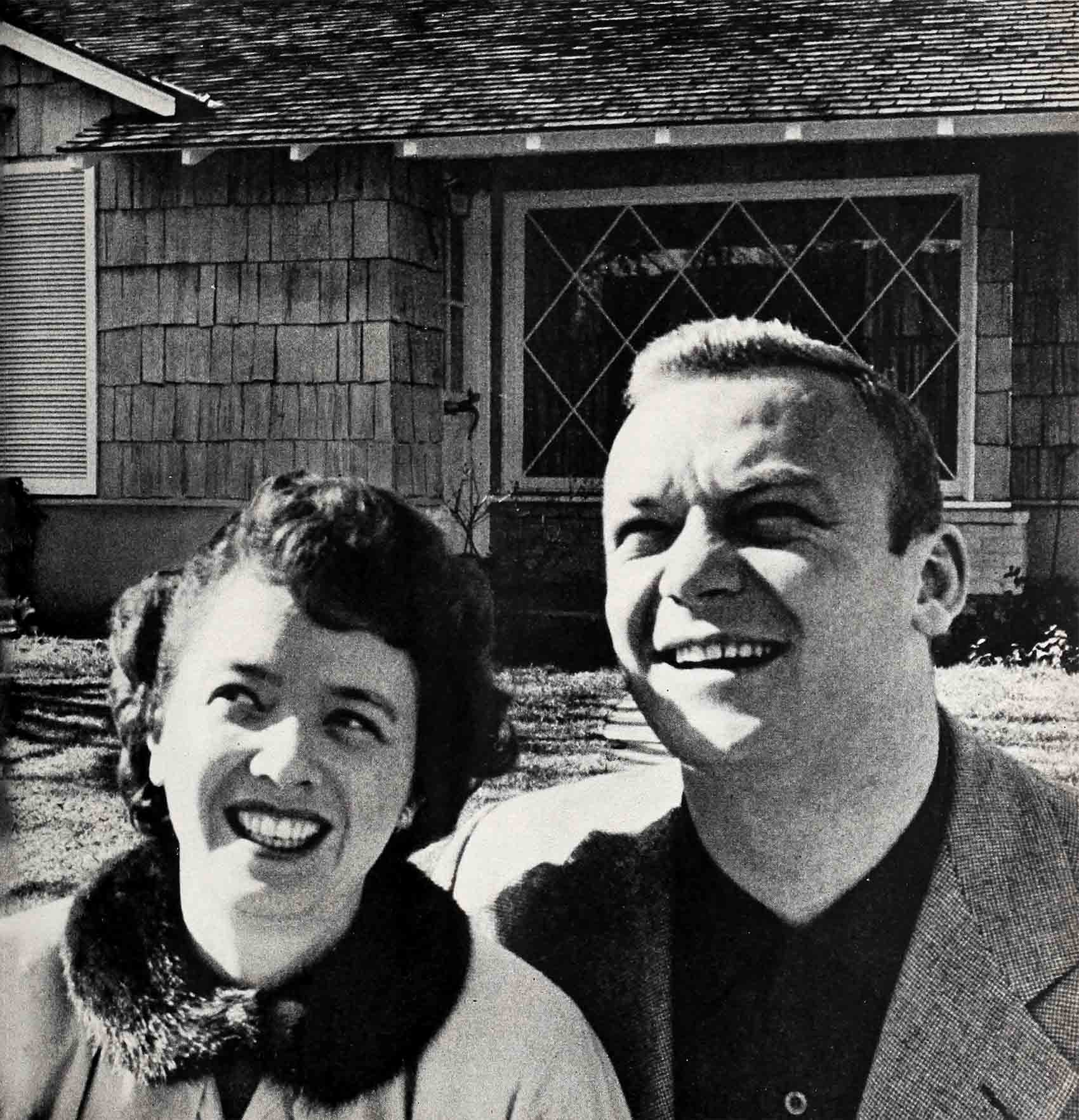

Who’s No Angel?—Aldo Ray & Jeff Donnell

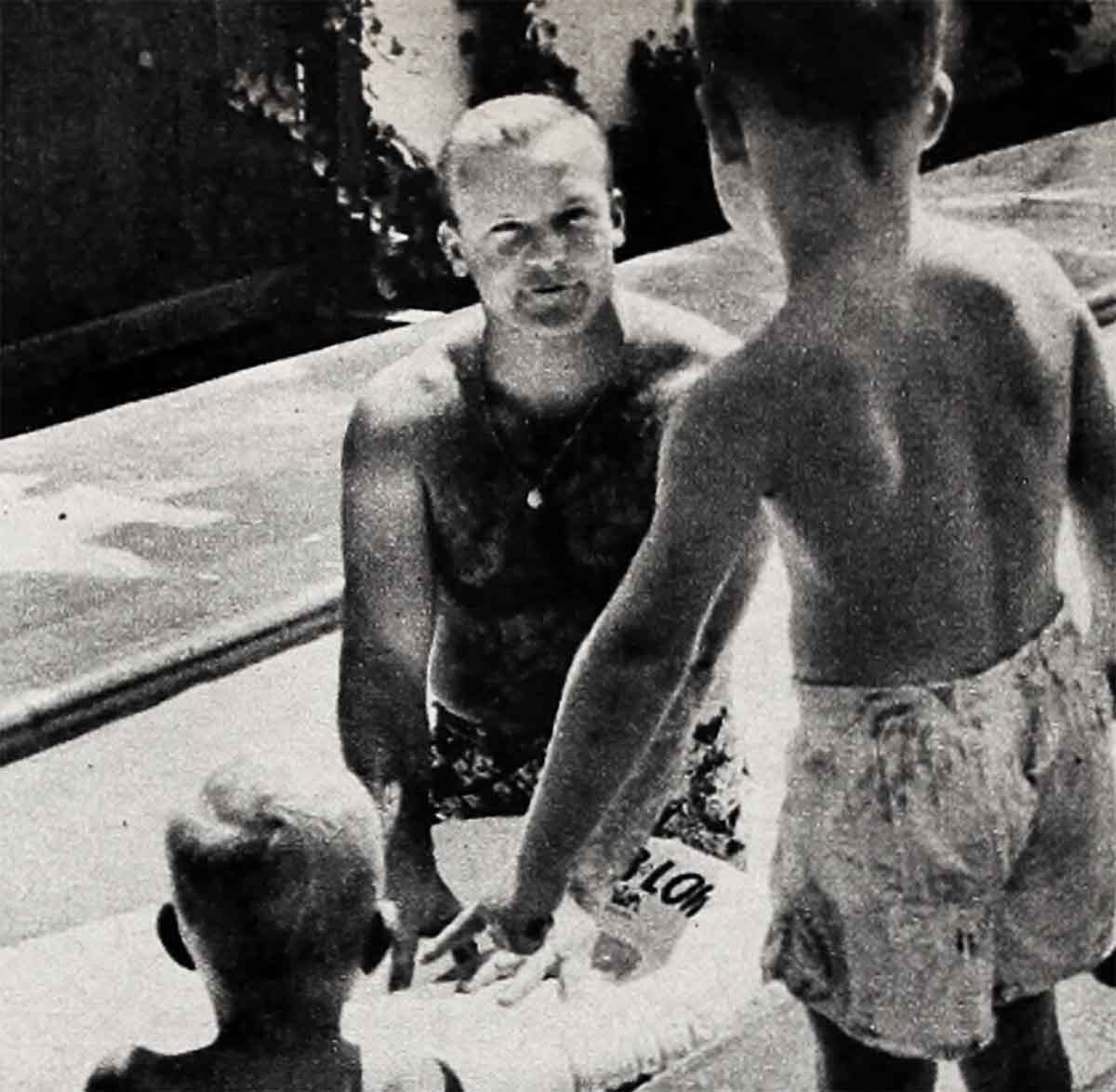

Along a shady, tree-lined street in North Hollywood, in a lovely sprawling corner house, live the Aldo Rays. Their house is much like every other home on the block, with this exception—the doorbell doesn’t work. To raise the household, one must be clairvoyant and beat on the door at the exact moment. Aldo, Jeff, Sally or Mike might be peering out from behind the front window. This is no easy feat—they’re usually elsewhere. Behind the house, there used to be a back yard—until Aldo filled it in with brick, cement and water and converted it into a swimming pool. The pool, incidentally, is the reason why the Rays both drive around in old cars. They had their choice.

Every day, except Saturday nights when she plays to the whims of George Gobel, Jeff Donnell bows to a bigger, more whimsical guy whom she affectionately calls “Altitude.” If you think this is a joke, ask Alice—I mean Jeff.

“Before we were married,” Jeff confides dismally, “Aldo looked like a Greek god. He bought eight beautiful suits and was slicked up all the time. Now he looks like a—”

“Slob,” rasped Aldo coming from underneath the ground. He was still working on the swimming pool—in T-shirt and ragged jeans. “It kills me to slick up,” he confessed honestly. “Typical male story, I know. But men will thank me for being honest, won’t they dear?”

“And women will hate you,” responded his mate.

“My mother doesn’t hate me,” Aldo commented quickly. “Although Jeff thinks I’m cruel to her.”

“Well, you’re too blunt.”

“I merely said that her dinner was lousy. That sure was one time when her food experiment didn’t turn out.”

Conversation deadlocked, Jeff changed the subject tactfully, hinted that she’d like to see the work he’d done on the pool. “Ha,” his grin broadened. “It’ll be finished soon. Twenty by forty—enough room to really swim. Then,” casting a defensive eye at Jeff and covering his midriff with his hand, “I’ll swim down to a hundred and ninety pounds.”

Finding no sympathy in Jeff’s eye, he added ruefully, “Look, I burned my hands. That new brick I laid in the patio. I found the cement had chloric acid.

Jeff and Aldo are happy. They planned it that way. Friends use to plague them with “When are you two getting married?” Finally, when everyone had given up, they married. “The reason was a very practical one,” says Aldo. “We had to be sure we had enough money for marriage.” Aldo, the oldest of seven children, six boys and a girl, knew poverty as a kid. “My father was a poor laborer who sacrificed all for his family—and Mother sacrificed even more.” Aldo’s careful consideration for money was understandable and Jeff realized that for him happiness had to be planned—like their house, their swimming pool and Jeff’s holdout with his studio for better roles.

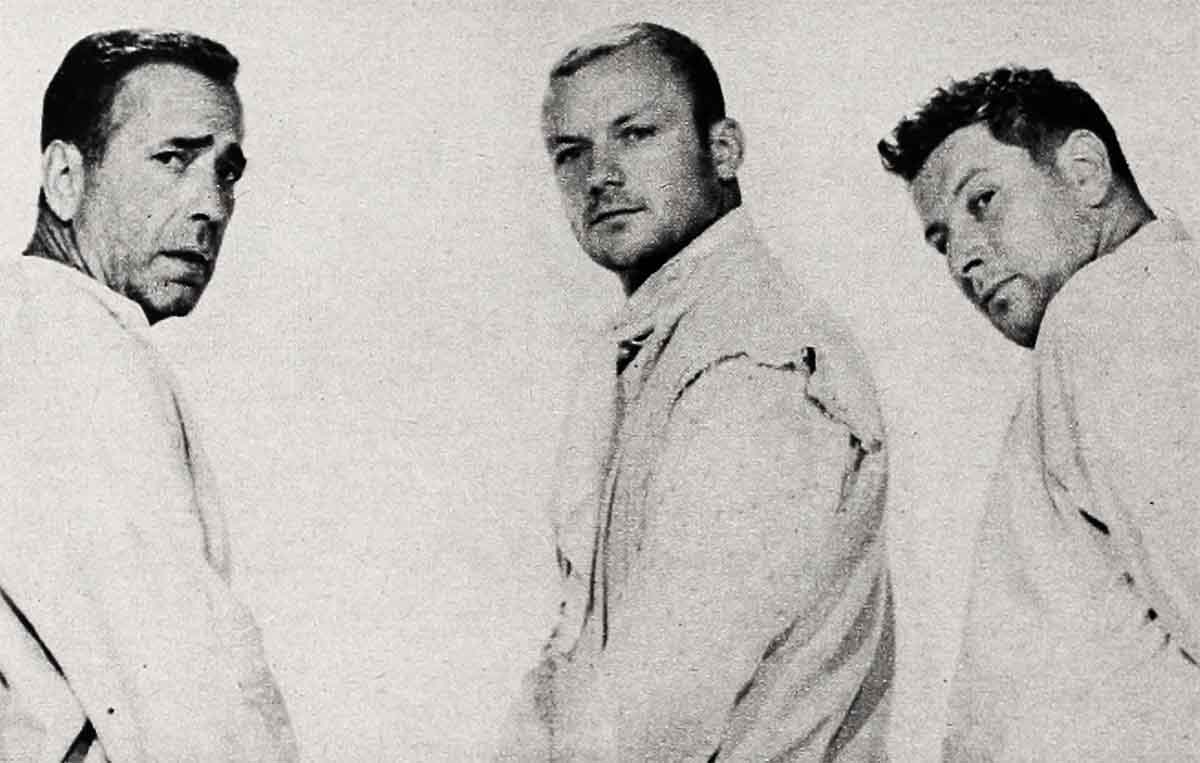

With the success of “We’re No Angels,” Aldo thought it time to take a stand for better roles. He refused “Jubal Troop.” His career is important to him, but so are the roles he plays. He took suspension on the chin with his natural good humor. “Now I’ll have time to enjoy people.”

“Aldo loves meeting people,” Jeff confides. “He has kind of a happy vitality that people like to get close to. Mrs. Hammond, who’s been with me and the children for years, has fallen in love with him. Now everything takes a back seat to Aldo. If we can’t find her, we know she’s in her room, filling her scrapbook with his clippings. Recently, Aldo filled in for Marlon Brando at an award dinner of the Sound Technicians Union. He loved it. ‘With my voice, nobody knows better than I do how important you guys are,’ he thanked them. And you should have seen him at the Hollywood Woman’s Press Club party. All those women and one man. He was in his glory. For a minute, when he came in, he was thrown. But, of course, he would never admit it.”

“Admit what?” interrupted the object of the conversation. “I’ll admit anything. I admit I think special days for special things are ridiculous. Like Mother’s Day, anniversaries, Father’s Day, dog day. Name it, I think it’s crazy. I like to remember people with presents when I feel like it and I don’t want an advertising genius to tell me when to honor my mother. I admit it.” He disappeared again toward the back yard.

“Aldo’s really serious, you know,” Jeff explained. “For two reasons, I think. One, he really does hate to be told—his whole family is that way. But the other reason, I think, is that they didn’t have enough money to celebrate birthdays, anniversaries, Mother’s and Father’s Days, and he just naturally built up dislike for the idea.”

Mike, Jeff’s young son, came cautiously into the living room. “Is he out back?” he asked with a conspiratorial wink. “I hid it where he can’t find it. Okay?”

“Okay,” his mother affirmed. After the introductions, she explained, “It’s not as mysterious as it sounds. It’s just Aldo’s birthday present. He’s really like a small boy when you give him a gift. Mike washed both cars to get enough money to buy it. He couldn’t decide between bullets for hunting or an axe. That’s why I was so bushed this afternoon—I ran him all over North Hollywood. Aldo smelled a mouse and he’s going crazy trying to get in on it. He can’t stand a secret. That’s why he pops in unexpectedly. On his birthday he protests like mad, but he loves every minute of it.”

“Loves every minute of what?” interrupted Aldo as he came through the door. “What do I love, huh?”

Jeff looked at him in despair as he sidled self-consciously to a chair, settled himself into the conversation. In a monotonous, singsong voice she started: “Aldo Ray was born in Pen Argyl, Pennsylvania, September twenty-fifth, nineteen-twenty-six. He was one of seven children. He . . .”

“Everybody knows that. I know that. You know that—everybody knows that. Crimenently!” he said in a George Gobel voice with a heavy cold. “Hey,” he roared suddenly, “I gotta prize possession. Gotta show you.” He disappeared toward the bedroom a la Gobel.

“Aldo gets a bang out of my being Mrs. George Gobel on Saturday nights,” Jeff said. “They have a mutual admiration society. Saturday nights I have George in front of me and Aldo behind me.” With that Aldo bounced out of the bedroom, struck an attitude and flexed his chest muscles. He had changed one white T-shirt for another. The only difference was that this one had “Lonesome George” written across the front in three-inch red letters. “How about that?” asked husband number one. “I go to the store in this and I really get the attention.”

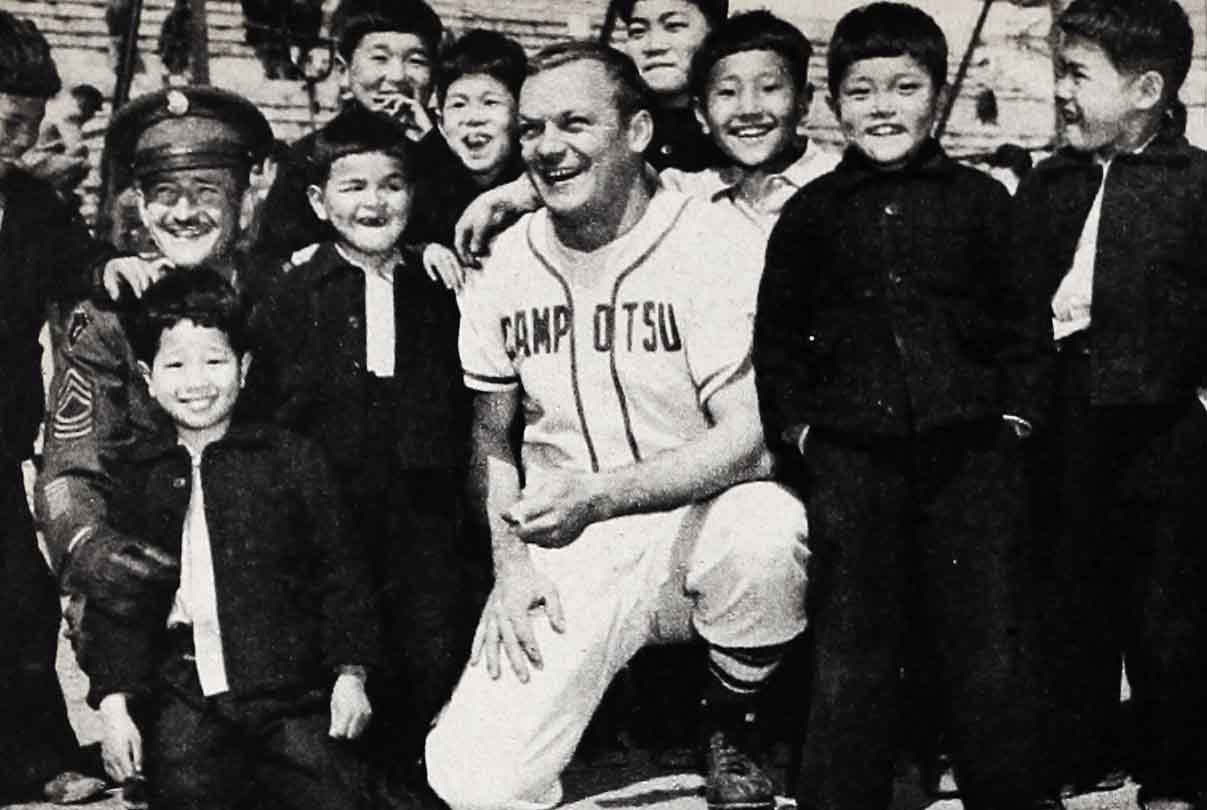

“You get plenty of attention from me after you go to the store,” Jeff responded dryly. “When he shops, he buys the best steaks, anchovies, the very best. I go and buy the makings for a casserole. It makes for an erratic diet—the case of the plain and fancy food. Of course, he’s a wonderful cook. Does mad things with food—always experimenting. Terrific on fish, liver, steak, barbecues, veal. On his first personal-appearance tour, he ate his way around the country. When he was in Japan, making ‘Three Stripes in the Sun,’ he was so busy eating he didn’t have time to write me.”

“You got one letter to your five.”

“He’d rather phone than write. He is not practical about the telephone,” Jeff added. “From Texas, Honolulu, Japan.”

“Look who’s talking,” Aldo interrupted. “Who called who in Japan?”

“Who called whom,” corrected Jeff.

“All right—whom called whom in Japan?”

“That was different,” Jeff’s voice softened and the banter was all gone.

“Yeah,” came a quiet growl of acknowledgement, “that was different.”

The living room was silent for a moment, both remembering how excited they were to begin a family. They bought an acre lot in Encino, planned their dream home on paper. Then Jeff lost the baby and had to call her unhappy news to Aldo in Japan.

“I used the brick from the Encino lot on our patio today. We were going to build there, but with the house, retaining wall, landscaping, furniture and a pool it would have run around sixty thousand dollars and that’s ridiculous. So we decided to build a pool in the back yard here and stay. It’s big enough and it’s comfortable.

“You know, it’s practical,” he continued, throwing off the momentary sadness. “We both work, so we have to have two cars. One’s a ’fifty-one and one’s a ’fifty-two. We figured it up. A new car costs more than a pool. And with maintenance and all it’s even more expensive. Also a car you gotta trade in—a swimming pool you’ve got forever. It figures.

“Our friends are right here in the neighborhood, too. If someone gives a barbecue, we all chip in on the steak and bring our tables along.

“Folks around here aren’t trying to prove anything to anybody. We’ve got a tire salesman in the next block and . . .”

“Aldo,” Jeff admonished with a reproving chuckle.

“And a bust developer salesman,” he continued blithely. “I just love to throw him into the conversation and Jeff always dies when she knows it’s coming. Anyway, we don’t believe in going in over our heads in the buying department. I like to pay cash.”

“Aldo learned to be responsible when he was a kid,” Jeff reflected as he left the room. “As the oldest of seven kids, they were all looking to him for the answers by the time he was in high school—even his mother and father leaned on his advice. They all knew Aldo would be somebody. To them, he was somebody then. Maria, his mother, is adorable. Aldo suddenly got the idea of buying a big refrigerator for her a few months ago. He drove it all the way up to Crockett just to see his mother’s face when she got it. Maria was thrilled with it, but she keeps the old one ready on the back porch, just in case the new one breaks down. Years of being careful can’t be wiped away quickly. When Aldo gave her a huge television set, she thought it pure extravagance.

“Aldo says he’s not sentimental,” Jeff continued, “and he’s not, in the usual sense. His love runs deep for his family and he takes it out in sudden, unexpected acts. Like the time he was in New York and suddenly thought of Maria’s brother. He looked him up and had him over to the hotel. They swapped stories for a while and Aldo said suddenly, ‘You haven’t talked to Maria for twenty-five years. Tonight, you talk.’ He got his mother on the phone in Crockett and put his uncle on. When Maria realized she was talking to her brother, she started to cry. The uncle started to cry . . .”

“And I started to cry,” added Aldo from the doorway. “For fifteen minutes while the dollars ticked away, those two sat at opposite ends of the country not saying a word, just crying. So I sat looking at my uncle and I cried.

“I have a dream,” he said abruptly, placing the coffee and settling into a chair. “Someday I am going to send my mother to Brazil to see her father. He has a big ranch there. When Maria was eight, he sent her to Italy. Then she came to Pennsylvania, married Papa and came West. Someday I’m going to send her to visit the father she hasn’t seen for forty years. He is a handsome white-haired man. While she is gone,” he said, changing his mood abruptly, “Papa can dance with Jeff.”

Jeff grinned, “Last New Year’s Eve I spent the whole evening dancing with Papa. The house was bursting with DaRes. Aldo was out in the garage trying to sleep on an Army cot. He had an early morning call. So Papa and I danced until I was worn out. He could have gone on forever.”

“The boys drop in all the time,” Aldo explained. “They just pop in when they’re in town. Dante will be here pretty soon. He’s stationed in Long Beach waiting to get his Navy discharge. Mario,” he shook his head sadly, “will not be with us much longer.”

“For heaven’s sake, Aldo,” Jeff said sharply, “he’s only getting married. He’s not dying.”

“Remember the time the studio took me out to USC to take pictures of my brother Mario and me?” Aldo said with a proud smile.

“I do,” retorted Jeff. “Those girls kept driving by the campus waving and calling. And our hero here waved and called back, making like a movie star. Finally it dawned on my knight that the girls were waving at Mario—not Aldo. Who was Aldo? Mario was a big campus football player!”

“Dante is the funny one,” Aldo commented getting his long legs comfortable on the ottoman. “One day he drops in and I say, proud-like, ‘Hey, Dante, I’m going to make a movie at M-G-M.’ Real quick he comes back, ‘What are you going to do, the Lion’s roar?’ Sharp tongue, sharp eye. When he was a kid, he went out and shot a hundred and fifty wild birds for food. Boy, we had birds for a week and a half, every way Mama could think of to cook them. It saved the day.

“Dante’s wonderful around the house. Once he painted a friend of our’s house because I bet him fifty cents he couldn’t do it. They paid him of course, but you just can’t never say ‘you can’t’ to a DaRe.

“My mother, ever since I was in the seventh grade, she expected great things from me,” Aldo reminisced. “So did I; I expected to be president. But she was afraid of my drive. Always felt I might push too hard. Things are different for Louie, my five-year-old brother. He is a real personality kid. He’s got big black heavy eyebrows and, when he gets mad, he squints his eyes and those eyebrows arch just like the devil’s. He’s got a mind of his own, too. When Mother started to drag him to the show to see ‘The Marrying Kind’ for the fourth time, he dug in his heels and howled. ‘No, I’m not going. I’ve seen enough of Aldo.’ He was able to sit through it three times, though. How am I doing?” he winked at Jeff, as she shooed him out of the room.

“Even though Aldo kids around a lot, he takes his work seriously,” Jeff explained. “He’s a natural actor and works hard at it besides. I’ve watched him grow on the screen and I know he can do anything—and will. I don’t say this in front of him often, but . . .”

“But what?” asked Aldo, bouncing into the room with Jeff’s daughter, Sally, on his arm.

Jeff stopped, burst into a wonderful warm smile. “I don’t say it often—but you just can’t get them types of husbands like Altitude no more.”

THE END

—BY DEE PHILLIPS

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1955