Why Don’t You Sound Like Mommy Any More?—June Allyson

It was 10:25 a.m. Within a matter of minutes June Ally son would know if she would ever speak again. She got out of the cab, followed by her secretary Maggie Sandstrom, and looked up at the swirling fog that was beginning to shroud the San Francisco skyline.

She had always loved the fog, just as she’d always loved San Francisco. In the past, the city had always meant good times, fine food and a sense of exhilaration. But on this day, the city and fog seemed to hold a growing sense of terror that was overwhelming.

She must control herself . . . she must. She took a deep breath. Breathing, at least, was one thing she could now do well. No longer did she have to endure the feeling that air was being squeezed from her lungs. Surgery had changed all that.

As Maggie paid the driver, June slowly turned and looked up what at the gray front of the medical building. It was no different from any other in the cubist pattern of San Francisco structures, but it held a very special meaning for June. Her hand found Maggie’s and squeezed it tightly.

“Don’t be frightened,” Maggie said, as she led her into the building. “You’ve waited a long time for this day to come, June . . . a very long time.”

They entered the elevator, and the two elderly ladies who were also passengers nudged each other.

“You’re June Allyson, aren’t you?” said one. June smiled and nodded and Maggie said, “She is sorry, but she can’t speak.”

The two women raised their eyebrows and looked at each other questioningly.

June closed her eyes and sighed. It had been like this only six weeks, but those six weeks of absolute silence had seemed an eternity. Why . . . why . . . when she had waited so long for this first visit to Dr. Moses, was she experiencing this growing fear?

They had told her she would speak again. A tracheotomy was a fairly common operation. Hers had been more difficult than average because of a gigantic growth in her throat—a growth that had threatened a quick death through blockage of air to the lungs. It had been there, unsuspected, for a long time. So long a time that for years she had been speaking only with throat muscles. Her vocal cords, they told her, were weak from disuse, and she would have to learn to speak all over again. But they had assured her that Dr. Moses, the specialist in San Francisco, would be quite able to help her learn to talk properly. Dr. Moses, one of the very few voice therapists in the world, had done marvelous things for people who had had voice boxes removed, for those whose vocal cords were paralyzed.

June’s case wasn’t nearly that serious, of course. She knew that, but somehow there was always the lurking doubt that her doctor hadn’t told her everything. The suspicion had eaten away at her during those weeks of enforced silence, and by now she was dreading the first attempt at speech. If they hadn’t told her everything, it was quite possible she would not be able to utter anything but uncontrolled sounds. She remembered a beggar who had once approached her, a sign around his neck proclaiming he was a deaf mute. She could hear, as though it were yesterday, the low gurgle of sounds that had come from his throat, and she shivered.

June is no stranger to pain or courage. There was the back injury as a child, when a tree had fallen on her. She spent long months in the hospital, and for years after, she was tortured with a steel back brace. She had had pneumonia three times, an appendectomy, and then the two operations to remove the polyps from her throat.

Why was she so frightened?

Yes, life had brought her more than her share of physical pain, and she tried now to reason with herself about this first visit to Dr. Moses. Why was she so frightened? It was so unlike her. Of course, it was possible that the whole thing had come too soon after her divorce from Dick Powell. That in itself was enough for any woman to go through, but two operations on top of an emotional strain might have been too much for her. It hadn’t been pleasant, being told that she had been near immediate death all those months. Her surgeon had said that any exertion, even climbing stairs, could have closed the tiny gap left in her throat for air passage. The emotional upset of the divorce could have brought on asphyxiation. And then, of course, there was the nagging fear that she had cancer.

Surgery, of course, couldn’t be delayed. The first operation hadn’t been too bad, even though they’d had to make a slit in her throat to allow breathing during the operation. The second had been much worse—more than three hours on the table, and afterward, the swelling and the bleeding that hindered recovery. She had to lie in bed for endless hours without moving because of the danger of hemorrhage. She supervised the house, communicated with the children by means of written notes. She wrote so much, her hand ached so, that the pain sometimes kept her awake. But the hardest part of all was remembering not to try to speak, particularly when the children needed cautioning or reprimanding.

During those weeks of silence, her constant companion was her dog, Mr. Bumpley. Because she showed only high spirits to the human beings in the household, she found solace with Mr. Bumpley, who shared her burden of being unable to speak. She realized fully what the term dumb animal means, and often during the night the dog’s black and white fur was damp with June’s tears.

Visitors were not allowed because the doctor had discovered June tired easily and her emotional strain was heightened by company. So she had spent the time in solitude and, against her will, had brooded about the divorce and the troubles that had led to it. As a result, her throat was slow in healing, and the surgeon told her she could not go to San Francisco to work with Dr. Moses until she had healed completely.

was advised. How to know how she would sound. And, yet, this very anxiety hindered the healing. It had been a vicious circle.

Finally, just yesterday, Monday afternoon, her surgeon had said he was satisfied with her progress, she could leave for San Francisco immediately. Within hours, she and Maggie checked into the Fairmont Hotel. After a sleepless night, she was finally here, finally in Dr. Moses’ office—and she was terrified.

Suddenly, a nurse was saying. “Miss Allyson? Come this way, please.

“Now,” thought June. “Now! I must pull myself together.”

Dr. Moses rose from his desk chair as she entered and came toward her with outstretched hands. He was tall, gray-haired and smiling. “Good morning, Miss Allyson,” he said, with a distinct foreign accent. “I am going to fix it so you will no longer talk like a boy.”

Had she been relaxed. had this meeting been under any other circumstances, she would have laughed heartily at his remark. But this particular morning, she could only manage a very weak smile.

“First,” he said. “I will look at your throat.” He placed her in a chair, adjusted the mirror on his forehead, and asked her to open her mouth.

Terror swept over her. Suppose Dr. Moses should look in her throat and not like what he saw? Her surgeon had said the operation was successful, but just supposing this doctor didn’t agree supposing he said she would never speak again.

She tried without success to open her mouth—it was as if her jaws were frozen. Her eyes clouded and she shook her head miserably.

A traumatic experience

“Come now,” said Dr. Moses. open the mouth.”

She couldn’t. Nor could she open it during the afternoon appointment, nor on her visit the following morning. Dr. Moses realized it was a traumatic experience for her, and he switched tactics. During those first three appointments he talked to her gently, showed her books and pictures of throat anatomy and patiently explained to her how simple it was going to be. She must, he said, first determine her natural tone, and from there they would begin. “You will see,” he smiled. “You will speak like a girl when I am finished.”

He used diathermy, wrapping her throat in a cloth and asking her to hold a small machine in her lap. It was a process designed to relax her from top to toe.

By Wednesday afternoon the tiredness. the discouragement had fled. She opened her mouth. Dr. Moses peered down her throat and then smiled.

“You are beautifully clean. It is a splendid surgery. Now, I want you to put your finger along the side of your nose, like so. I want you to hum. Feel the vibration? I will put my finger on the other side of your nose. like this. so that I can feel it, too. Now. I want you to hum high up and then go down the scale . . . There! Right there. That is your natural tone. This is the tone in which you will learn to speak. Never speak until you feel that particular vibration, then you will know you are right.”

June looked at him, her eyes wide with wonder. Was speech really so complicated as this? Babies just talk, and that was that. It was all so very simple. But this. this was going to take control. Perhaps this was where the final patience would be required.

“Now.” said the doctor, his finger on a key of the organ he uses to determine pitch, “you will make, in this tone, a noise like a cow. I want you to say moo.”

June formed the word with her lips, but no sound would come.

“I can’t.” she said, and her heart sounded with surprise at the sound of her voice, the first sound in all those weeks.

“Aha!” said Dr. Moses, grinning. “You see, you can speak. But please say what I want you to say. These sounds will strengthen your vocal cords.”

She went back to the hotel with a list of sounds to practice several times a day, always being careful to use the tone designated by the doctor.

It was so strange, and so wonderful to be making sounds again. Maggie teased her that never again would the household have the peace it had known, that soon she’d be bellowing through the house until cups and saucers shook on the shelves.

It didn’t sound like her

But June’s feeling of terror did not go away. She was making sounds, true, but they were not her sounds, it was not her voice. Things came out much higher than they used to. Richard Powell had always said her voice was her fortune. But she didn’t care whether she got the old Allyson voice back again, all she wanted, all she prayed for was to be able to speak. Yet these sounds frightened her. It was so strange to speak and sound as if someone else were talking. It was the same shock you would experience if you looked into a mirror and saw someone else’s face.

The doctor realized her concern, and the next day suggested she sing something.

“Sing?” whispered June. “How can I sing if I can barely talk?”

Dr. Moses looked at her out of his wide brown eyes. “Try. You will see. Sing lyrics that have the ‘oo’ sound.”

She chose “Do You Love Me?” The result was one of the unforgettable experiences of her life. The song came out, clear and strong—and soprano. She sang notes she had never been able to reach before. In fact, after a full ten days of work with Dr. Moses, she could hit high C.

June’s speaking voice was high-pitched, too—high-pitched, weak and wobbly. She wanted to phone the children in Beverly Hills and assure them she was doing well. But she knew if she spoke to them in this funny voice they would worry. So Maggie made the phone call and announced that June would sing to them. Pam and Rick got on the phone, shrieking with excitement. Frank, June’s devoted houseman, got on another extention. She sang “Over The Rainbow,” and in Beverly Hills three faces took on a look of disbelief. They couldn’t believe it was June. Maggie had to get back on the phone and assure them it had been.

The work with Dr. Moses continued, two sessions a day. June wrote highly amusing letters to friends, telling them she wasn’t able to talk very well, but she could sing the socks off “The Barber of Seville.” She wrote: “I’m doing fine. Doctor told me he has never seen a more bewitching throat operation—and then he said I had to change from this extremely low register to a medium register. Well sir, I accomplished that all right, except we have created a monster! Now I can hit high C! And now the poor doctor’s problem is to get me out of high C down to medium register—where I refuse to go! I’ve never been up here before and I find it fascinating.”

Her cheerful notes fooled her friends, but not Maggie, who would hear June trying to warm up her voice with exercises. The sounds would come weakly at first—“Ma-my-moo-may-MAGGIE!!” Nor did she fool Dick Powell, who flew up for a visit with her. At dinner with her ex-husband, she tried, with gay banter, to relieve his worry. She told him how the hotel staff had been told she couldn’t speak, and how on the third day, one woman had asked her a question. The woman, suddenly remembering June’s predicament, hastily added, “I’m so sorry, I forgot you couldn’t talk.” June smiled forgiveness then said, “Good night, and thank you very much.” June’s words had surprised them both.

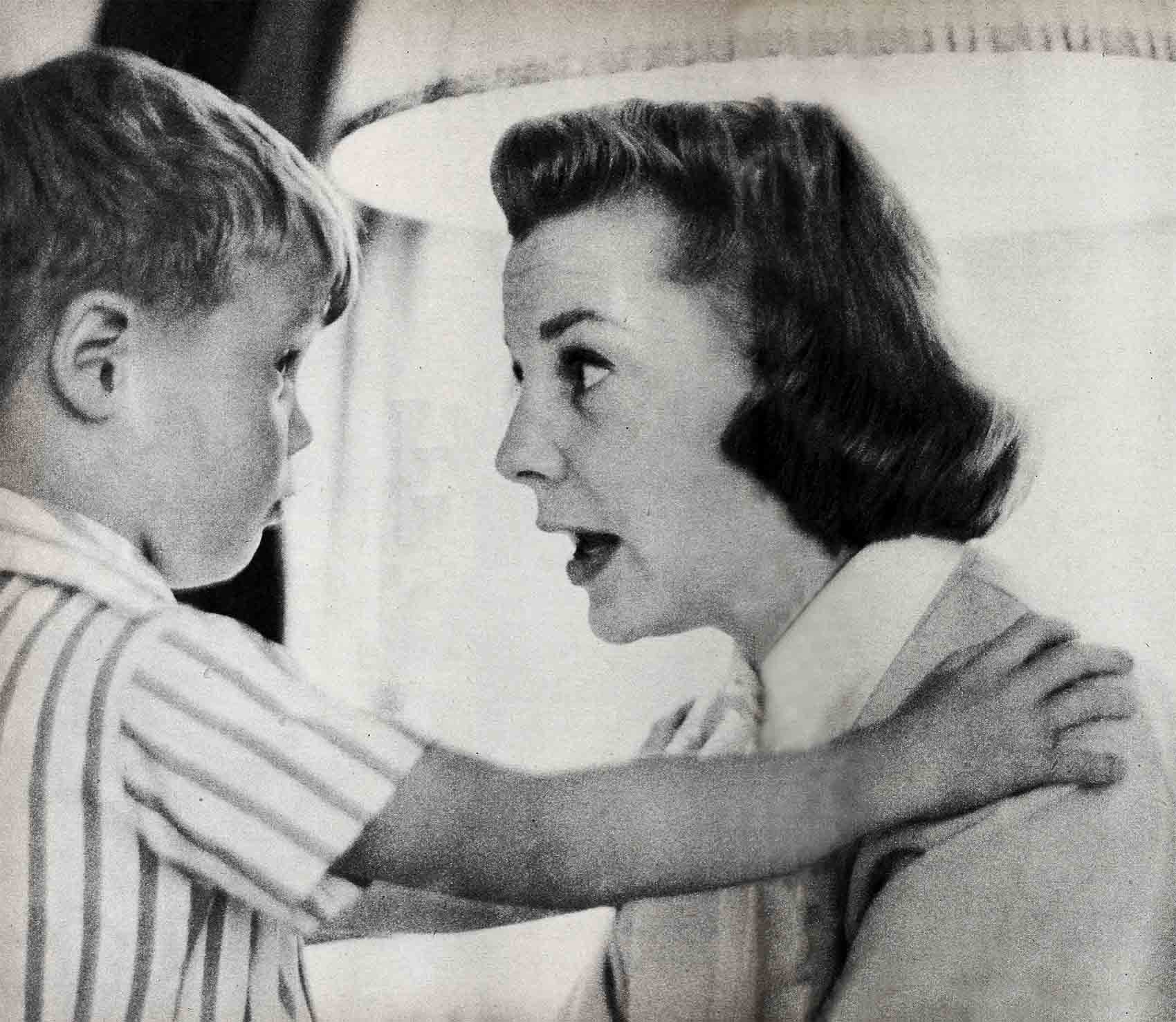

In front of the children

But her voice was extremely weak, especially when she was tense. Dick realized that June had a long row to hoe. She needed patience and work, work and patience.

After ten days in San Francisco, June was told she could return home for the weekend. Now she must speak in front of the children—she could postpone it no longer. How would they react? What would they think? Would she seem a stranger to them?

She turned the key in the brass doorknob and the wide white door of her home swung inward. Within seconds, her two children came tumbling through the house to greet her. They fell against her, jockeying for position, and she buried her face in their hair, still postponing the moment they would hear her voice. Then Pam and Ricky stood back and demanded she speak.

She took a deep breath and said, “Hello, darlings.” It came out terribly high, almost squeaking. She could do better, but this was an emotional moment, and whenever she was tense there was trouble with the voice. She hated the sound, and looked to them for reaction.

They stood riveted, their eyes wide with astonishment. Pam struggled to hide her surprise, but Ricky had no such feminine artifice.

“Why don’t you sound like Mommy any more?” he said. Pam jabbed him in the ribs, but it was too late.

June fought back the gathering tears. This would not do; it simply would not do. She managed a smile and beckoned them to the couch where she pulled them down, one on each side of her.

Fighting for control, she breathed deeply. “I am . . . I am going to say a great deal to you now. My voice is not like it was, and I know it sounds strange to you. But no matter how I sound—and if you think it sounds funny so do I, so you may laugh at me whenever you want—but no matter how I sound, I’m still your mother and I love you very much and I always will. And if . . . if you think it’s important that I speak the way I used to, then some day I will. I promise you that.”

Pam put her arms around June and kissed her on the cheek, and Ricky gave her a quick hug. “C’mon, Mom, I’ll show you my new model car.”

It had been difficult, but it was over. It was over, and they were accepting her. As the weekend passed they became fascinated by her exercises and would sit and listen, their lips silently mouthing the sounds along with her. Rick would say, “Now I’ll be a cow.”

Then June and Maggie went back to San Francisco for another week, and during that time June’s voice strengthened and settled considerably.

At the end of the week, the doctor told her she could now speak as much and as often as she wished, but that she must do the exercises religiously, several times a day. She was to go home and relax, eat properly and gain some weight. He would want to see her in another month or so to make certain she was working on the proper tone.

Back home, June did as she had been told, and as the weeks went by, she discovered with delight that she could now telephone friends and be recognized without announcing herself. The singing voice was still high, and June regaled the house-hold with her fine soprano. Frank became convinced she would “one day be a great singer.”

The last thing to sink into medium register was the “soprano laugh.” This had been a source of amazement to everyone, including June. It began with a schoolgirl giggle and took off into the heights. Every time it happened, June had a momentary urge to look around the room to find out who was laughing. Others were concerned about her laugh, but she wasn’t. It was so wonderful just to be able to laugh!

A few days ago, June was in her bedroom, running through her exercises for what must have been the thousandth time. They were an idiotic collection of sounds, and she was so self-conscious about doing them that she tried to do them when no one else was around. She was in the second string of moos when Ricky wandered into the bedroom. He looked at her with all the disgust a young boy can muster, clapped his hands over his ears and muttered, “Good grief! Not again!”

June’s laughter thundered through the house and carried straight into the kitchen where Frank was peeling carrots. He began to whistle happily. Miss Allyson was her old self again.

THE END

—BY JANE WILKIE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1961

zoritoler imol

31 Temmuz 2023I have been exploring for a bit for any high-quality articles or weblog posts on this sort of space . Exploring in Yahoo I eventually stumbled upon this website. Studying this information So i?¦m glad to express that I’ve an incredibly just right uncanny feeling I came upon exactly what I needed. I so much indisputably will make sure to don?¦t put out of your mind this website and give it a look on a continuing basis.