The Very Private Life Of Marilyn Monroe

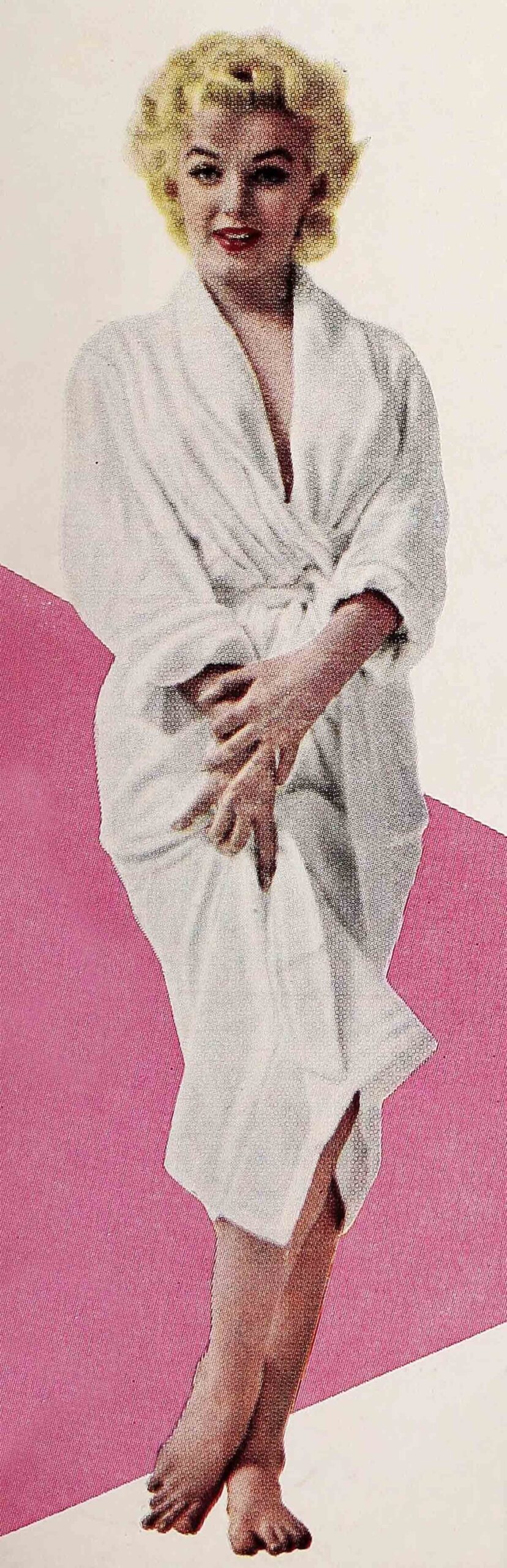

Marilyn Monroe is gone forever. Hollywood will get her before the cameras every now and then, but they won’t keep her. What they’ll be getting is a shell—the same dazzling shell their own publicity magicians created—but their girl is gone. It is even possible they won’t recognize Marilyn when she walks in. This year in New York has wrought an incredible change in her looks, her personality, her inner being. It’s the kind of reverse switch that would be outright fraud in anyone else, but in Marilyn it is the first breath of reality in her strange, bewildering life.

Unlike so many people running away from themselves, Marilyn knows exactly what she is running away from and where she is going. Much has been written about Monroe’s New Life, much of it sarcastically critical of a supposed attempt to be arty, intellectual, bohemian. But Marilyn is too sure of herself to be hurt by criticism. She is simply appalled by her own image, the Myth of Monroe, the near-parody of sex she has become. She isn’t looking for a new personality. All she is seeking—desperately—is the real one. The woman buried beneath layers of make-up and years of posturing, long hidden from everyone, hidden even from herself.

For the first time, Marilyn is fashioning a life without love. As always her closest friends are men—men have always guided her life—but today friendship is just that. No more, no less. Marilyn has learned to shed The Myth like a Cinderella gown, and with it all the frightening insecurity that brought her to this year of decision.

A few months ago, she was escorted on the spur of the moment to a small, intellectual party in Brooklyn Heights. Introduced simply as “Marilyn,” she wore a plain outfit and no make-up, and none of the guests recognized her.

For all they knew, Marilyn was a young actress trying to get a break in television, or perhaps a model with strangely simple, almost sloppy taste in clothes. She entered freely in the conversation, which was mainly about art and literature. As the party was breaking up, one of the lady guests asked innocently what she did for a living.

“I’m an actress,” Marilyn said, with equal innocence.

“Qh?” said the other woman. “Stage or television?”

“I’m in pictures,” said Marilyn. “What name do you use?” the woman asked politely. “Monroe,” she said.

“Monroe,” repeated the guest thoughtfully. Then she looked more closely at her and did a double take. “Good heavens! You don’t mean—!”

Marilyn chuckled self-consciously at the guest’s surprise. There was a good laugh all around. But for Marilyn it had been a pleasant evening because the secret was slow in coming out. She was accepted as a person, not doted on as a movie star. No one had even mentioned the dirty word Hollywood.

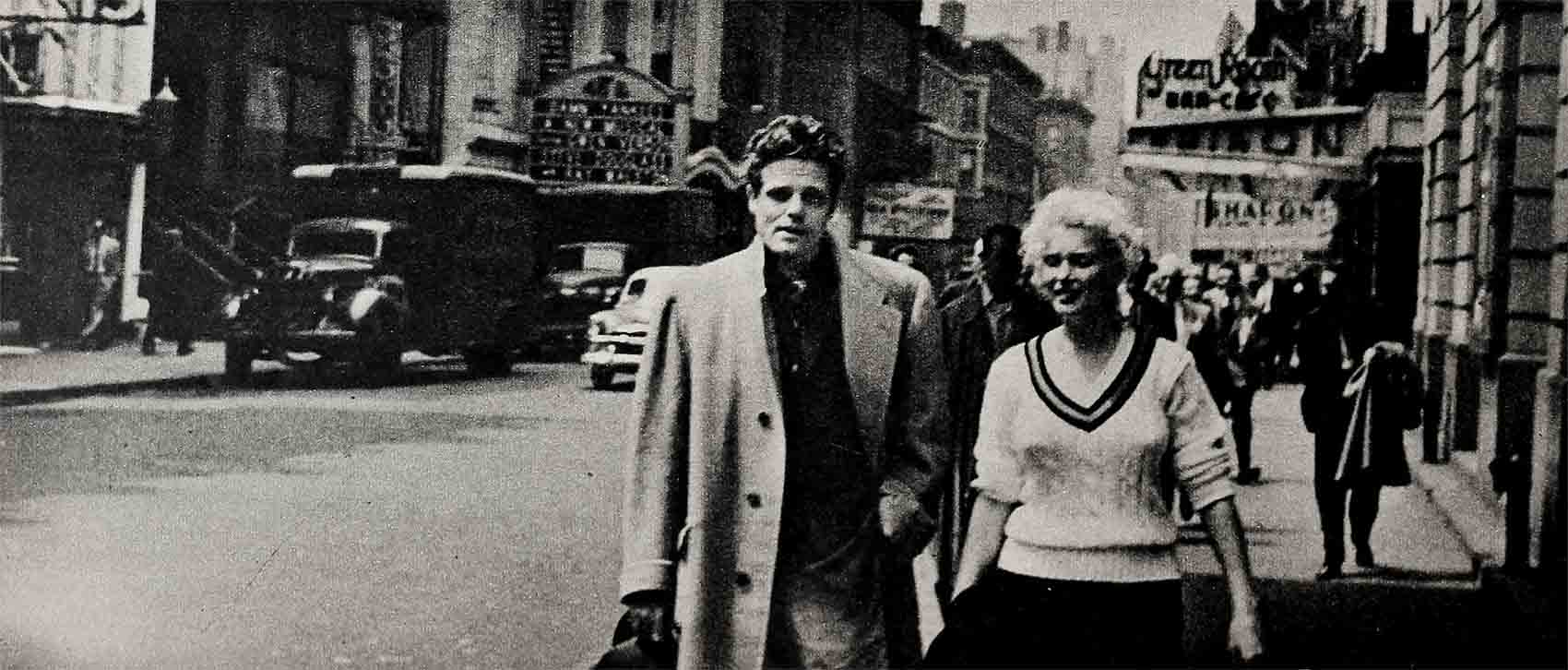

One of the principal reasons New York delights Marilyn is that it readily affords such anonymity. Although great crowds turned out to welcome her at public appearances, she could lose herself at will—and did—among its teeming millions. Without face powder and mascara, she became just another pretty blonde among thousands.

This vacation from fame, with all its time-consuming responsibilities, allowed her to pursue her dramatic studies. She had barely settled in New York when she was admitted to Actors’ Studio, a sort of post-graduate school for established performers. It was in this atmosphere of dedication that she hoped her talent might at last mature.

Actors’ Studio is a unique institution. Today, it may well be the single most important influence on the American theatre. It has helped to shape a whole raft of young actors, from Marlon Brando to Harry Belafonte. Its main emphasis is on realism, but not at the expense of imagination. Marilyn’s great dream is to become a part of the school’s tradition.

Not that she will ever forsake Hollywood. Far from it. Marilyn appreciates the rewards of success as well as the next girl. She is simply resigned to playing the dual role of movie queen and earnest student of drama. If the contradiction bothers her, she refuses to admit it. But a double life has obvious pitfalls.

Marilyn expects to commute between Hollywood and New York, making her money out west and improving her acting back east. It is significant that when one of her colleagues at Actors’ Studio asked how long she intended to remain in New York, she blandly replied: “Why, I live here now.”

The basic aim of her studies is versatility. As Brando has turned to song-and-dance after years of heady dramatics, so Marilyn wants to try her hand at serious roles. When she announced last winter her ambition to play Grushenka in The Brothers Karamazov, scoffers hooted from coast to coast, but the laugh was really on them. They neither appreciated how well-cast she might be in the part, if a movie version were ever made, nor did they understand what she had in mind.

“I wasn’t talking about the present,” she patiently explains. “I don’t want to turn my back on anything. I want to do good musicals, good comedy, or anything good. Grushenka is just the juiciest part I know.”

And it so happens, despite her disclaimers, she does know how to spell Dostoevski.

Marilyn’s intellectual bent is nothing new. She has long tried to compensate for a sense of inferiority by improving her mind. Her well-educated musical taste runs from Beethoven to Bartok. Back in 1951, she was taking literature courses at U.C.L.A. Visitors to her home have often marveled that her library contained books by Rilke, Wolfe and Robert Browning.

When Dame Edith Sitwell came to Hollywood a couple of years ago, she was asked to invite a movie star for tea. Her instant choice was Marilyn Monroe.

The invitation was duly extended as a lark. It was expected Marilyn would wonder who the devil Dame Edith was. Instead she proclaimed herself a great admirer of the British poetess and would be honored to attend. The two women hit it off famously.

This year, Dame Edith publicly invited Marilyn to visit England so they might meet again. “Of course I’d be delighted to play literary mother to her,” she said. “Marilyn is a serious-minded girl.”

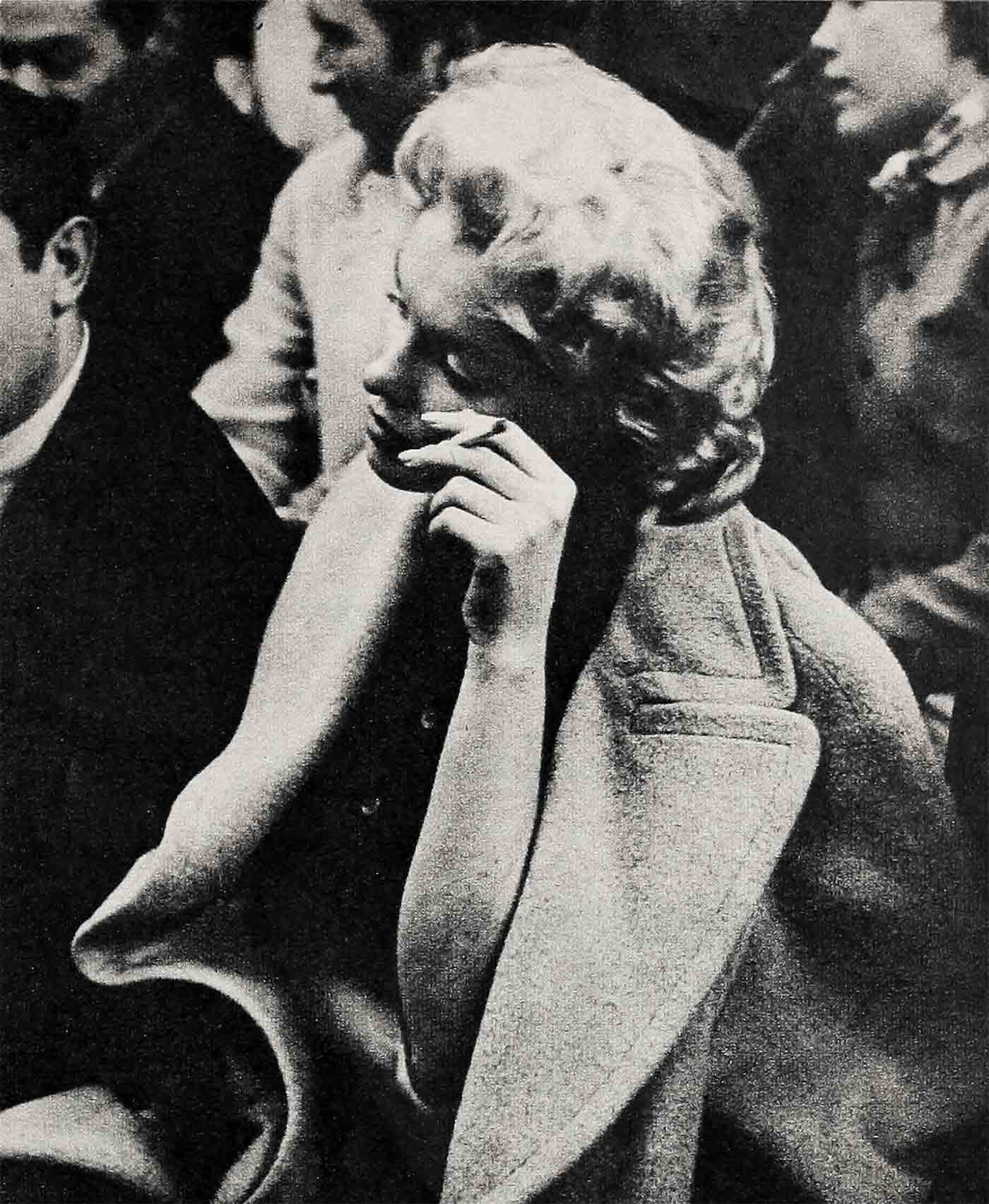

Her native intelligence is similarly recognized by other students at Actors’ Studio. At the start, her position was admittedly difficult. Not only is Marilyn retiring by nature, but her classmates were prejudiced by her notoriety as a movie siren. Furthermore, after years of being fawned over, she had to adjust to being treated as an equal, if not a downright inferior.

On her first day, she arrived while class was in progress. All the chairs were taken, so she had to slump down on the floor as inconspicuously as possible. No one stood up to offer her a seat. Uncomplimentary remarks were made behind her back about her hair, clothes and profile.

When class was over, she was a lonely figure, unapproachable because of her reputation, yet anxious to make friends. Waiting on the sidewalk for her limousine, she looked for all the world like Little orphan Annie abandoned by Daddy Warbucks.

She made plenty of friends, however, in the weeks that followed. Her colleagues found her bright, charming and self-effacing. They came to respect her motives, though many doubted she could attain her goal. Skepticism dies hard, especially on Broadway.

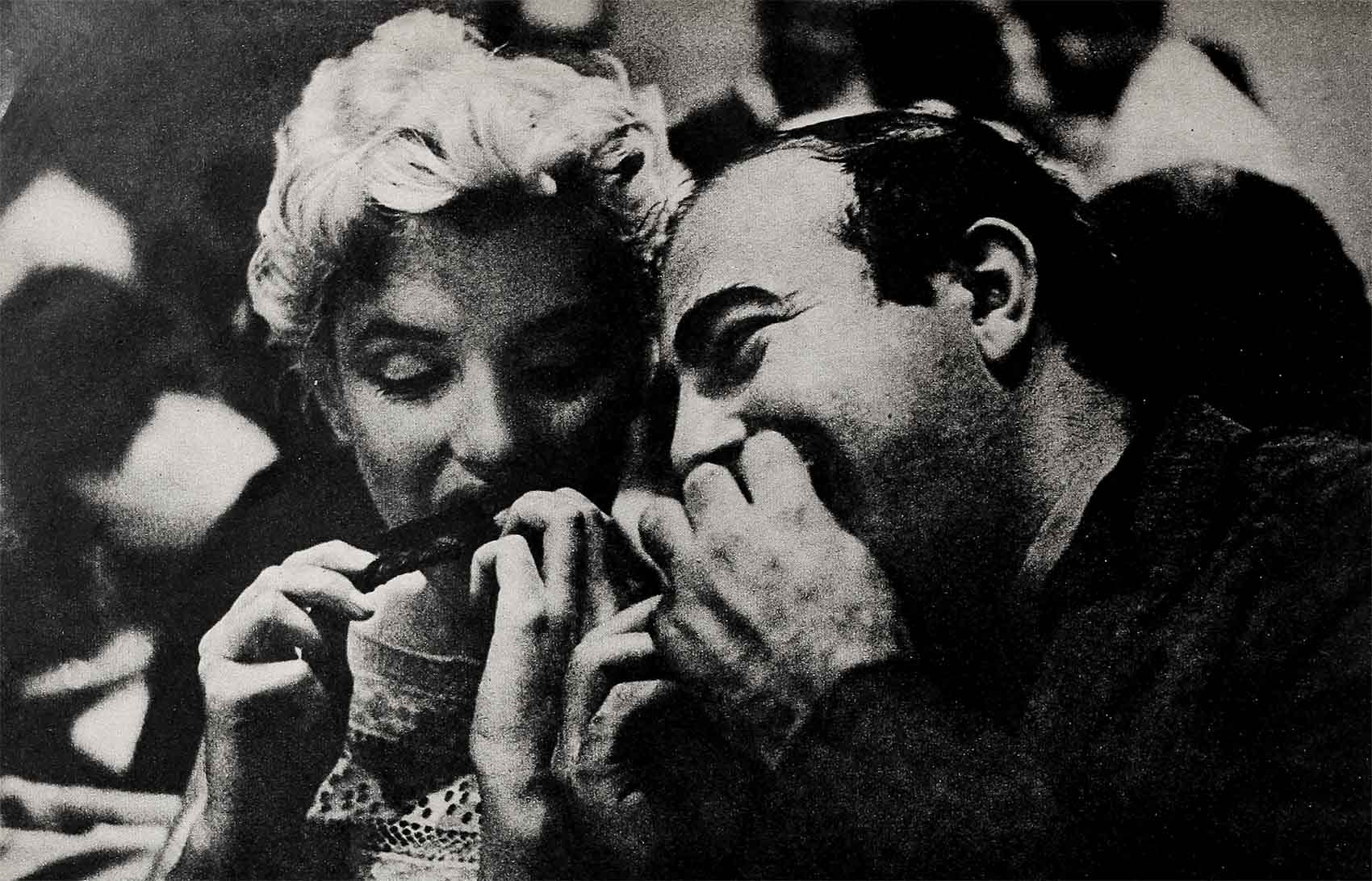

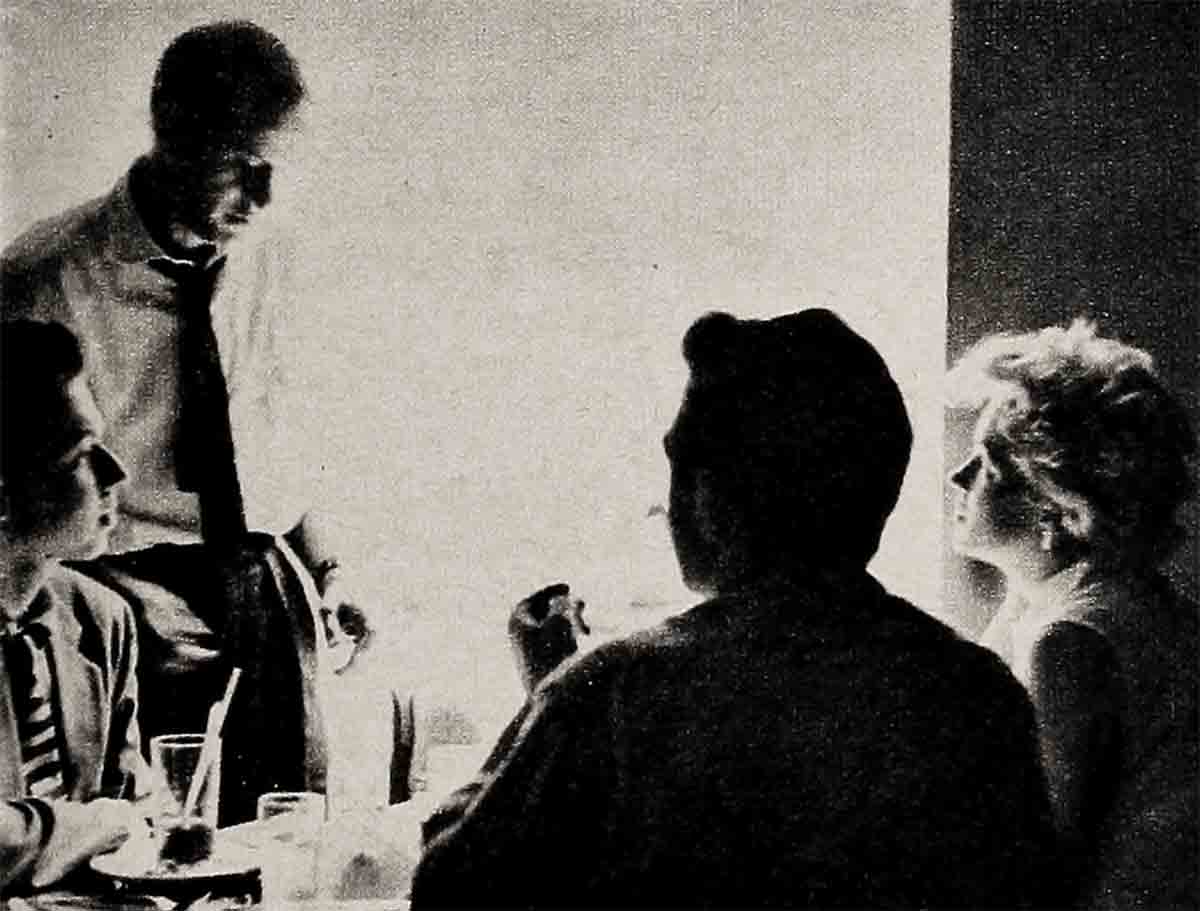

Marilyn turned up for school looking like an unemployed ingenue. After classes, she often had a bite to eat with her fellow students. Among her warmest friends were Eli Wallach and Ben Gazzara, both noted Broadway actors, with whom she had heated discussions at Childs about theatre and art.

One Sunday, she accompanied Wallach, his wife and their four-year-old son Josh on an outing to the country, where the youngster had the enlightening experience of going swimming with Marilyn Monroe. Wallach’s straight-faced report is that no one batted an eye.

Yet her role remained decidedly ambiguous among her new-found friends. On the one hand, she was no less dedicated than they, and earned their admiration for it. On the other, she came down each day out of the clouds like a fairy princess—down from her suite in the Waldorf Towers. And sometimes her descent had the impact of dynamite.

At the opening of East Of Eden, which was a benefit to raise money for Actors’ Studio, a host of Broadway actresses obligingly volunteered to serve as usherettes. So did Marilyn, who stole the spotlight the instant she appeared, dressed to the teeth as a Hollywood star. There is a quality about Marilyn in that guise—part herself, part publicity build-up—which is positively explosive. Without her presence, the event wouldn’t have been anything like the walloping success it was.

This public magnetism constantly reminded her classmates that, unlike them, she had already gone west and struck gold. What they perhaps didn’t appreciate was her mixed feelings about California. Whereas they had migrated to New York for professional training, Marilyn had come east, in a tual uplift, perhaps even salvation.

Whether consciously or not, Marilyn couldn’t help resenting California. It was there, twenty-nine years ago, that she had been born in the charity ward of a Los Angeles hospital. (Her mother is still alive, supported by Marilyn in a nursing home.) Until her first marriage at sixteen, she was brought up by eleven different foster parents, passed around like a piece of goods. Naturally, such experiences left her starved for affection and grimly determined to prove herself.

For a long time, self-justification amounted to little more than keeping her head above water. Her first job was in an orphanage pantry, at five cents‘a month; later she was promoted to setting tables, at ten cents a month. In 1949, she posed for the famous nude photograph to earn enough money—a grand total of fifty dollars—to pay the rent.

Max was almost indistinguishable in those days from hundreds of Hollywood starlets, all striving for recognition. She seemed to have neither the extra talent nor beauty to reach the top. But she was fortunately befriended by the late Johnny Hyde, an agent for the William Morris Agency. He gave her the will and contacts to get ahead.

Although she was put under contract by several studios, nothing much came of it until John Huston picked her for the brief role of a trollop in The Asphalt Jungle, which sent her stock skyrocketing. Huston and Hyde were the first of several masterminds who shaped Marilyn’s career.

Her primary need has always been outside guidance. Lacking parents who might have instilled self confidence, she had to look beyond herself for values. Often life seemed chaotic and morality a hoax. In her drive for success, she was ready and willing to adopt whatever personality seemed to promise the biggest pay-off. With Hyde’s approval, Huston came up with just the right model.

Like a chameleon, Marilyn readily adopted the character, so different from her own, which Huston’s script called for. When Darryl F. Zanuck, production chief at Twentieth Century-Fox, signed Marilyn to a long-term contract, he was not signing the indecisive starlet of former days, but the open-mouthed blonde he had seen on the screen. Marilyn was stuck with it.

But her sudden success didn’t give her the satisfaction she had expected. Plagued by illness and self-doubt, she took two hours to put on make-up for public appearances—including her celebrated press conference to announce her divorce from Joe DiMaggio—because she was terrified of being revealed as a fraud. That was the basis for what Hollywood cruelly called her “Narcissus complex.”

As an actress, Marilyn relied heavily on her coach, a short, gray-haired woman named Natasha Lytess. She became critical of her own performances, and began to think of her talent as wasted on second-rate scripts. Gradually she discovered material rewards were not enough to compensate for her deep-seated guilt complex.

Meanwhile, Zanuck had managed to project Marilyn’s image on the public as almost a parody of sex. People started laughing at Marilyn, rather than respecting her. On her trip to the Orient with DiMaggio in 1954, a Japanese radio commentator referred to her as “the honorable hipswinging actress.” In February of this year, twenty-three California stockholders in Fox publicly requested her removal from the payroll as “a blight on the company.” Her flaunting of sex had gotten out of hand, and Marilyn knew it.

That was the background for her battle with Fox. She turned down their offer of $100,000 a picture in preference for “some voice in the selection of stories.” After they had wrapped up The Seven Year Itch, Marilyn fled to New York until the hassle was settled, hoping to find there what the west coast had denied her.

“Marilyn looked upon New York as a shrine of culture,” says one of her intimates. “If only she worshiped reverently, all her dreams would come true.”

The chief strategist for her revolt was Milton H. Greene, the Look Magazine photographer. A brash, intelligent man of thirty-two, from the first time Marilyn sat for him he treated her as a human being, not a papier-maché idol, and gained her trust for it. Together they set up Marilyn Monroe Productions to handle her business affairs. Marilyn spent much time as a house guest of the Greenes.

But for artistic guidance, Marilyn turned to still another mastermind—Lee Strasberg, the most respected drama coach in New York. One of the co-founders of Actors’ Studio with Elia Kazan and Cheryl Crawford, Strasberg conducts private dramatic classes, which Marilyn also attended as an observer. She saw a good deal of Strasberg, including week ends with his family on Fire Island.

At last a serious artist of the theatre was taking Marilyn seriously. It was precisely the boost her morale needed. Now, by applying herself, she could scale the summits of pure art. But huge obstacles remained—and remain to this day.

Strasberg is a hard taskmaster. There is no “right” and “wrong” in his method of instruction, but only individual honesty. Under relentless prodding, the actor must project his deepest feelings to the audience. All else is phoniness.

Although Strasberg pales at the thought, his technique resembles psychiatric therapy. He strips his students emotionally bare and then forces them to parade in public. Several of his protegés, far less high-strung than Marilyn, have recoiled against self-exposure and fallen by the wayside.

Is Marilyn capable of facing the truth about herself? An old friend responds: “Perhaps this is one more case where truth is deadlier than fiction.”

Her whole experience has been an escape from reality. It is her way of overcoming the spectre of her origins. As an orphan, she has adopted a long line of “fathers” to fill the void in her life—from Johnny Hyde to Lee Strasberg. But if Strasberg is to keep faith with his own system, he must change all that and liberate Marilyn.

Most of her classmates sincerely hope for the best. They are touched and awed by her personal courage, which they recognized as one of her unsung traits. Success or failure is almost beside the point—the effort itself is tribute enough.

But the risks involved are very great indeed. It won’t be easy, at this late date, to change the vision her public has of her. The tightrope of her double life stretches dangerously from New York to Hollywood, and she won’t get down for love or money. At the dizzy height of stardom, her whole future hangs in the balance, both professional and private.

This is a crisis that Marilyn has long foreseen. Several years ago, she made a prophetic observation: “Women who put on an act are going to reach a time—everything is just a matter of time—when they’ll have to put up or shut up.” Now that time has come for Marilyn, and she has gallantly chosen to put up.

THE END

—BY WILLIAM BARBOUR

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1955

No Comments