Norma Jeane

PART II

Her story is hazy from the first and involves at the outset a troubled mother and an absent father. Gladys Monroe, who would give birth to Norma Jeane at Los Angeles General Hospital on June 1, 1926, was herself the product of an unstable home. She was born in 1902 and, as a little girl, witnessed the mental erosion of her father when syphilis attacked his brain and sent him to the hospital where he died, according to Donald Spoto’s Marilyn Monroe: The Biography. Gladys was thereafter raised by a mother who eventually suffered from hallucinations and displayed erratic behavior, perhaps also caused by a physical illness. Gladys married for the first time at age 14; this husband, Jasper Newton “Jap” Baker, was more than a decade her senior. Together they would have two children, a boy catted Jackie and a girt named Berniece. After Gladys divorced Jap, he kidnapped the children and took them to his native state, Kentucky, to raise them. Jackie would die young, and Berniece would not see her mother again for 20 years.

Gladys then married Martin Edward Mortensen in 1924; she left him in early 1925, and their divorce was finalized in 1928. The question of who Norma Jeane’s father was is one that still lingers. Although it is unlikely that Mortensen sired the actress—Marilyn Monroe said she always imagined another man, whose photograph was once shown to her by her mother, as her father—Gladys had the surname Mortenson written in on Norma Jeane’s birth certificate, compounding the confusion by misspelling it. Then, on Norma Jeane’s baptismal certificate, Gladys gave her child the surname Baker, after her first husband.

Therefore: Norma Jeane Mortensen Baker, who one day would take her mother’s maiden name and alliteratively become Marilyn Monroe.

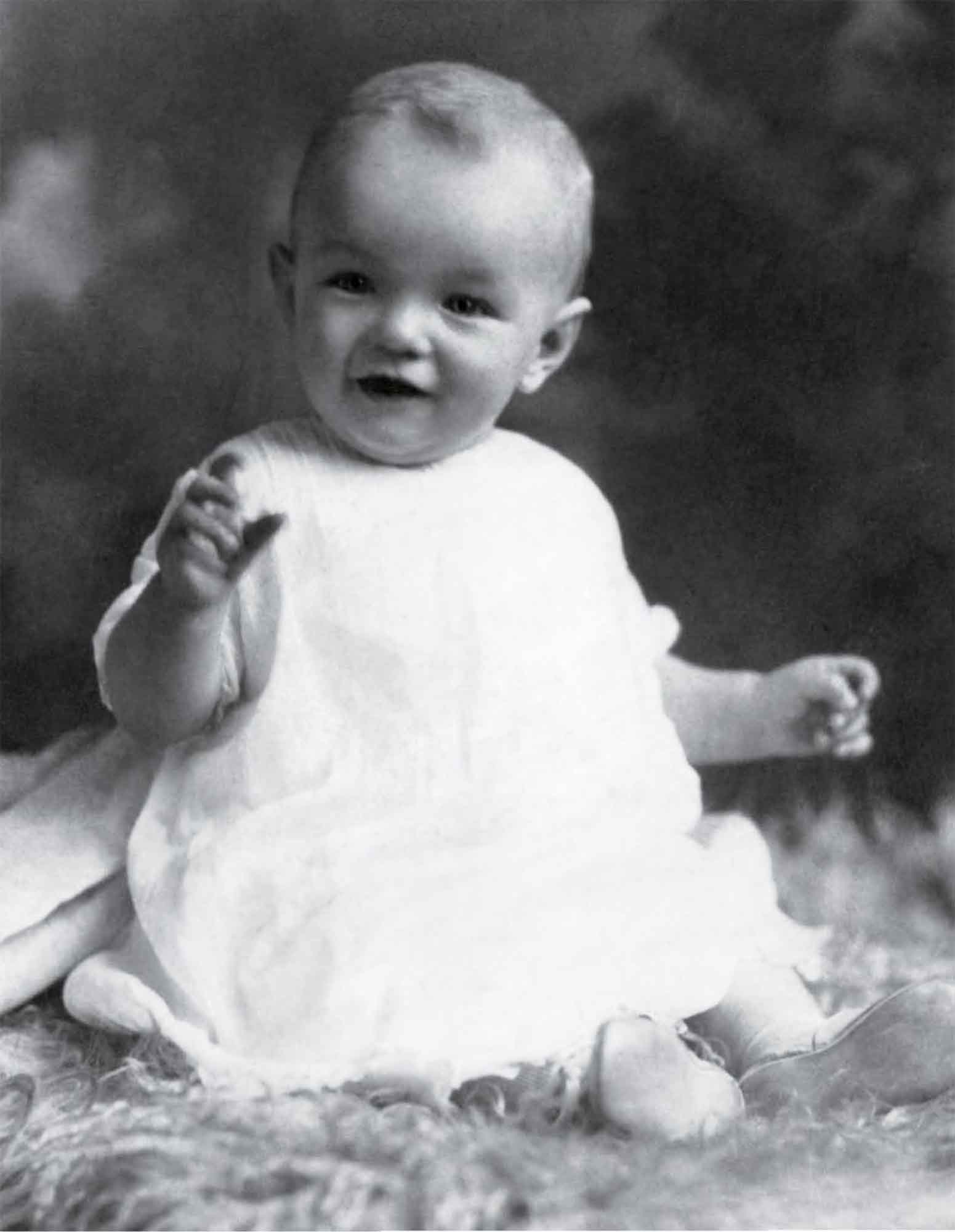

By the time Norma Jeane was born on that summer morning in 1926, Gladys was working in a lab cutting film negatives. There she befriended a co-worker, Grace McKee, and together, according to biographer Spoto, they earned reputations as risque, fun-loving flappers of the Roaring ’20s. Gladys, realizing that she was unable to appropriately care for her baby, within two weeks turned her over to a foster home—that of Albert and Ida Bolender, who, in Marilyn Monroe’s later recollection, were caring, if stern, and pious churchgoers. The couple took in a steady trickle of foster children for the extra income. Though Norma Jeane would see her birth mother on occasion, it would be 12 years, she would later say, before she ever felt loved.

Testimony from the Bolender house, where Norma Jeane spent her first seven years, differs from this sad account, asserting that Norma Jeane was a happy Little girt, and this contradiction provides us with a very early example of how the true story of Marilyn Monroe wilt always be elusive. The movie queen told a reporter in the early 1950s that the past was “an unpleasant experience I’m trying to forget,” and in many other tellings, the record of Norma Jeane’s youth has her bouncing among foster homes like a ping-pong bait. The semiofficial version surety represents a creative blending of fact and fiction by Hollywood publicists—and by Monroe herself, including the version she coauthored in her posthumously published memoir, My Story. As her close friend columnist Sidney Skotsky once wrote: “She was not quite the poor waif she claimed to have been.” Skotsky noted that the number of foster homes seemed to multiply as time went on because “she knew it was a good setting point.”

Whatever the precise details of Norma Jeane’s early years, they could not have been cheerful and carefree, and they certainty tacked the influence of a nurturing parent. In fact, confusion has to have been a dominant theme of her upbringing. The Bolenders would drill into Norma Jeane that going to the movies was a burnable sin; later, Gladys and Grace would entice her with the glamour and escape of the silver screen. Gladys would spend time with her daughter at the beach, and she must have shown some maternal affection. But their relationship was sufficiently distant that for a time tittle Norma Jeane knew her only as “the woman with the red hair.”

There was one attempt at a format mother-and-child reunion. In 1933, Norma Jeane left the Bolenders to live again with her mother, but Gladys suffered a nervous breakdown that year—Monroe later said she had watched as her mother, screaming and laughing, was taken by force from the house—and Grace McKee stepped in to oversee the tittle girl’s care. When Grace married Ervin Goddard in 1935, Norma Jeane, then nine, was sent to the Los Angeles Orphans Home, where she would spend up to two years (accounts differ); stints at other foster homes would follow. As for Gladys’s fate: She would spend many of her remaining years in hospitals and institutions, dying in a nursing home in 1984. She and Norma Jeane would remain virtual strangers, but Monroe, as soon as she was able, always saw to it—even in her wilt—that money was set aside for her mother’s care.

Grace McKee (now Grace Goddard), who formally became Norma Jeane’s legal guardian in 1937—taking the 11-year-old back into her own home—would prove an immense influence. She sought to fashion the child after her favorite film star, the blonde bombshell Jean Harlow. Grace taught Norma Jeane how to appty makeup; she took her to have her hair curled. For her part, Norma Jeane bought in willingly, avidly; at one point, she measured her hands and feet against the imprints of screen idols outside Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. Even at the orphanage, before she moved back in with Grace, Norma Jeane, her head full of dreams of stardom, found solace in the sight of the nearby RKO Pictures water tower—a reminder of Grace and Gladys, a totem of a thrilling existence on the horizon.

Into a young fife already brimful with tumult now came serious trauma. A short time after Norma Jeane became part of the Goddard household, Ervin Goddard, Grace’s husband, allegedly tried to molest her. Norma Jeane was then sent to five with her great aunt Ida Martin. There, at age 11, she was sexually assaulted by a cousin, according to biographer Spoto. Marilyn Monroe herself, in her memoir, talked of an even earlier attack, when she was eight. Norma Jeane was ushered further down the fine to the care of Grace’s aunt Ana Lower, and there she would finally find a safe harbor. This was where the girt who “felt like I was on the outside of the world” for the first time felt the warmth of love from— and for—her guardian.

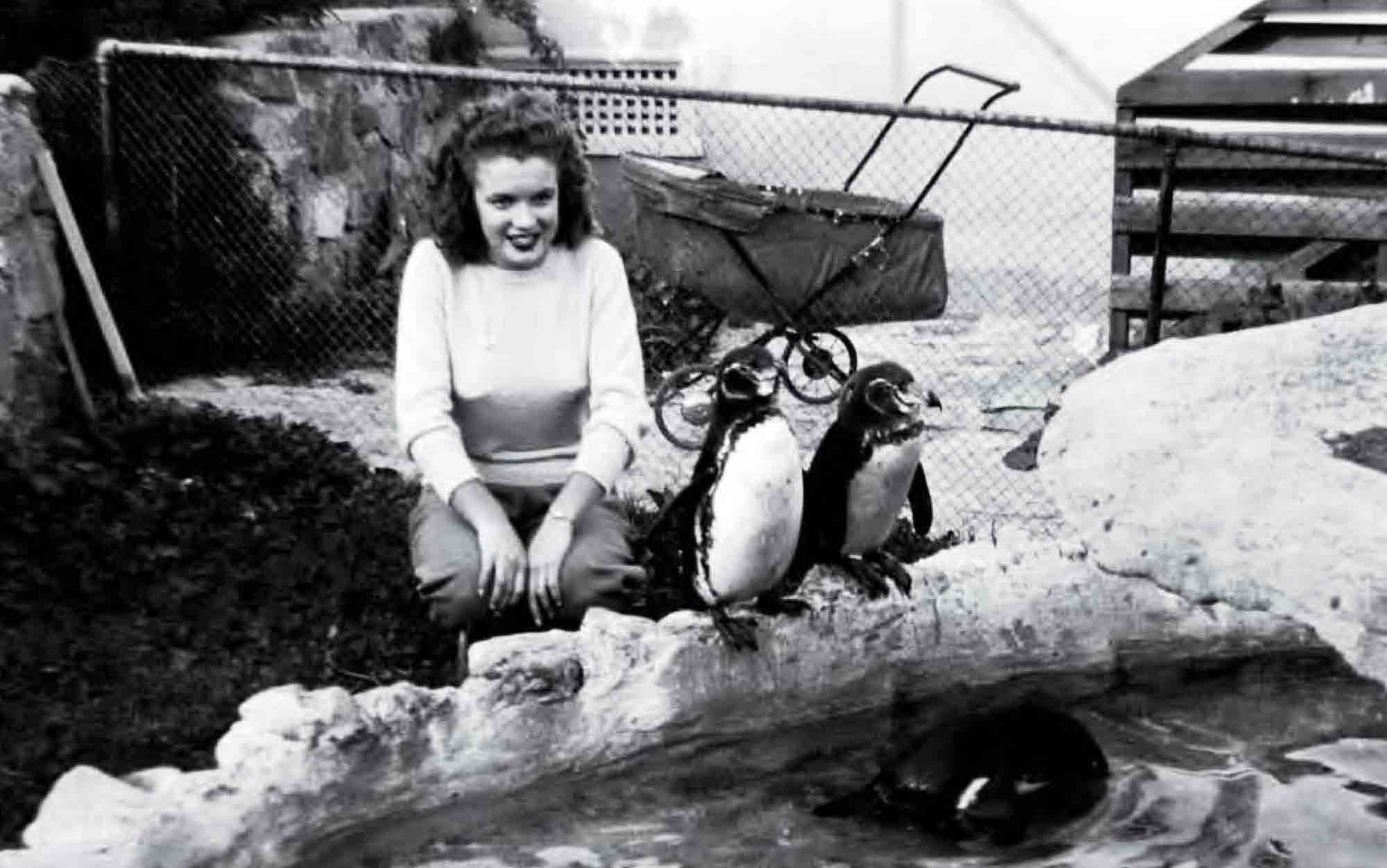

Norma Jeane faced another change as she entered adolescence. The unremarkable-looking girl who in school had been taunted as “Norma Jeane the String Bean” quickly developed curves. New nicknames would come; an early favorite of the boys, Spoto writes, was “the Mmmm Girl.” Marilyn Monroe would later recall, “The world became friendly.”

In 1942, however, the 15-year-old Norma Jeane found the world turning less friendly again. Ana Lower was stricken with health problems, and Norma Jeane once more returned to Grace’s care, but now Ervin, the household’s breadwinner, was being relocated to West Virginia. Norma Jeane was informed that the family wasn’t going to take her with them. Since her legal custodian was leaving California, Norma Jeane was faced with a possible return to the orphanage. (Some accounts say she did go back briefly.) Yet Grace presented her with a means of escape. She had already been playing matchmaker between Norma Jeane and Jim Dougherty, the son of a friend, who was five years Norma Jeane’s senior. Now, Grace proposed, the two shoutd get married as soon as her ward turned 16. Failing that, Norma Jeane would have to five in the orphanage until she reached 18.

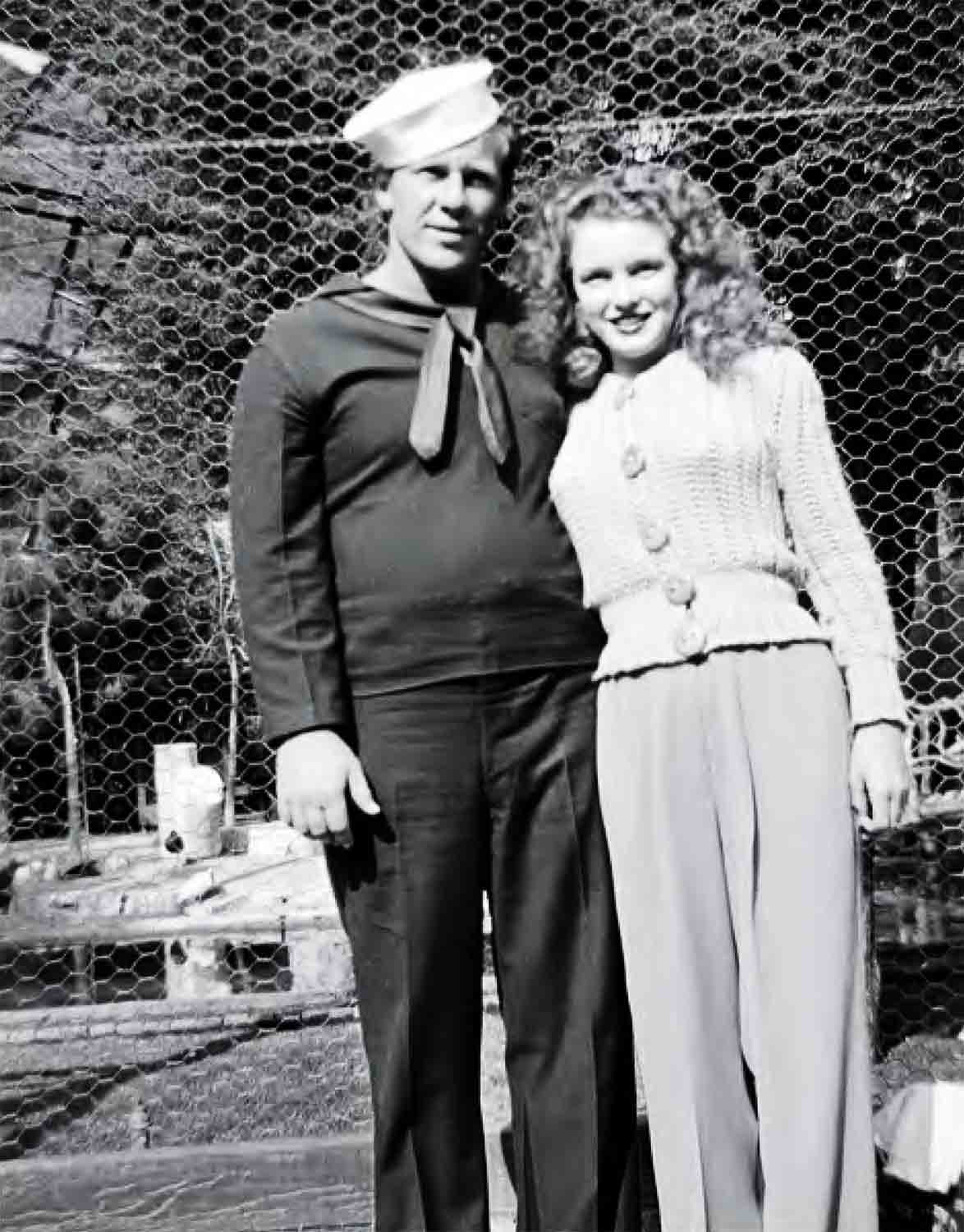

Norma Jeane made her decision and wed Dougherty in June of 1942.

Dougherty would later say there had been love in the relationship, but Monroe would remember things differently. “There’s not much to say about it,” she once recalled of the situation. “They (the Goddards) couldn’t support me, and they had to work out something. And so I got married.” She wrote in My Story that she never felt much like a wife in that first marriage and that her principal enjoyment at the time continued to come from playing with kids in the neighborhood. The union was destined to fast just four years.

During that period, in 1943, Jim joined the merchant marine and, after being briefly stationed on heavenly Santa Catalina Island, off the California coast, was shipped overseas in 1944. Norma Jeane moved in with Jim’s mother and did her part for the war effort at the Radioplane Company, where she spent tong days spraying varnish and folding parachutes.

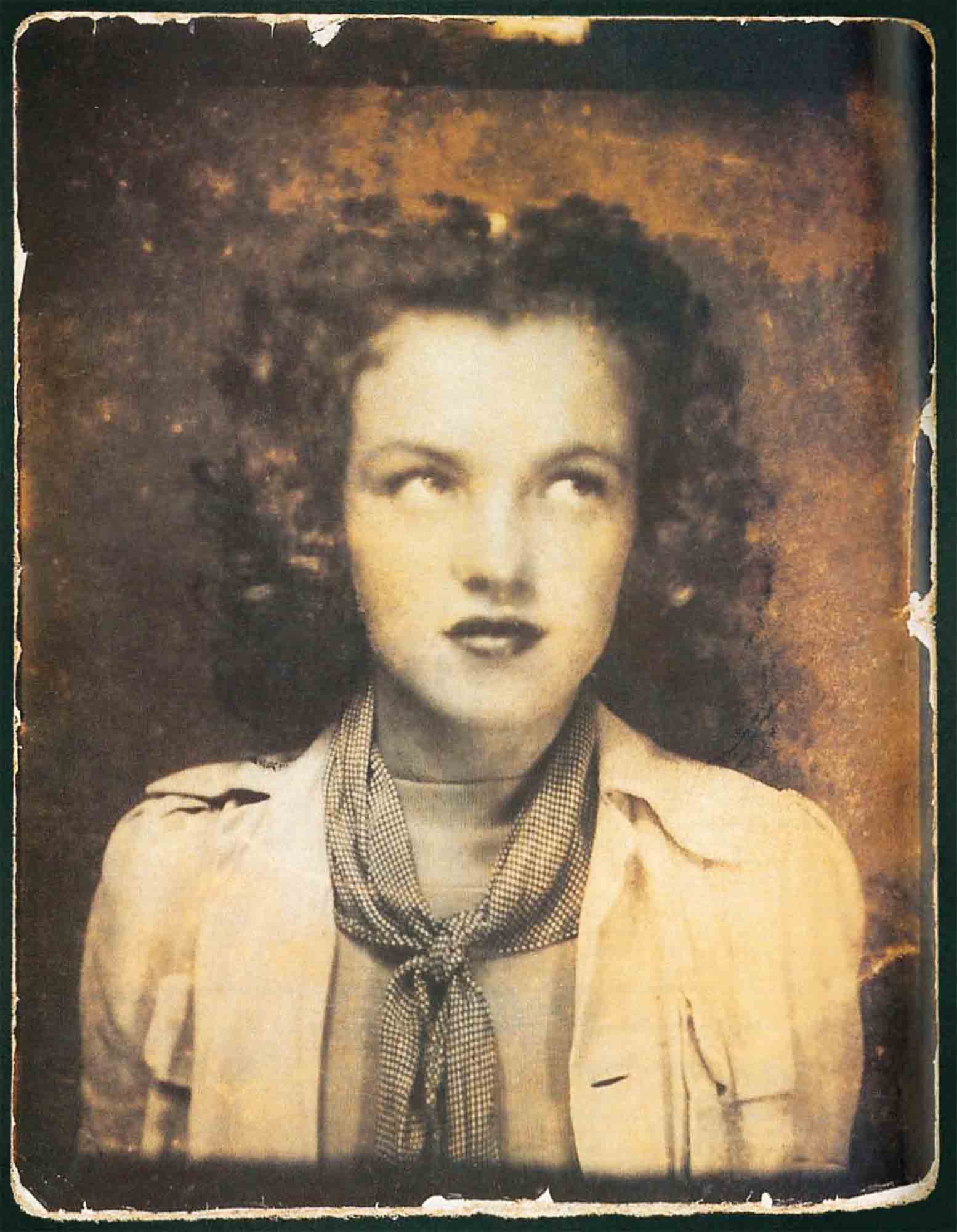

As it is in so many Hollywood sagas, the story of Mrs. Norma Jeane Dougherty’s being discovered and taking her first step toward becoming Marilyn Monroe—the lucky break, the critical meeting—came down to the right place and the right time. Army photographer David Conover was always on the lookout for attractive Rosie the Riveters to brighten his stories for military magazines, and the brunette Norma Jeane was attractive indeed. So much so that after photographing her, Conover suggested she try modeling and told her about the Blue Book agency. Norma Jeane took the tip, signed with Blue Book and in relatively short order became one of the firm’s top models. When someone said she might be even more successful as a blonde, Norma Jeane accepted this suggestion, too, and bleached her hair.

In 1945, she left the defense factory, determined to make the most of her breakthrough in modeling—a decision that displeased Jim Dougherty and served to hasten the end of their already-fragile marriage. She posed for advertisements and magazine covers but also artsy shoots with photographers like Andre de Dienes, with whom she had a brief affair (among others in this time period, perhaps). She worked seminude for pinup artist Earl Moran, who later recalled: “She Liked to pose. For her it was acting.” Of her talent in this regard, he added that she was “better than anyone else.”

That’s indisputably true. Throughout her modeling and film career, Norma Jeane continued to have a special rapport with the tens of a stilt camera. At the speed of a shutter blink, she leaped to life, displaying a verve alt her own and, at the end of the process, connected magnetically with the eyes of the viewer. Even the earliest photographers—and she would eventually be shot by many of the very best—found her skillful, discerning, cooperative, imaginative and utterly bewitching. In posing for the stilt camera, she exhibited none of the anxieties or neuroses that would haunt her movie career. And the photos captured over her lifetime are iconic in their own right—as much a part of the legacy of Marilyn Monroe as her film work.

In the summer of 1946, white in the midst of her divorce from Jim Dougherty, Norma Jeane, who had been brought to the attention of Twentieth Century-Fox recruiter Ben Lyon, was given a screen test. Those in attendance were unanimously impressed. “It’s Jean Harlow all over again,” said Lyon.

“I got a cold chill,” cinematographer Leon Shamroy told Colliers. “This girt had something I hadn’t seen since silent pictures . . . Every frame of the test radiated sex. She didn’t need a sound track—she was creating effects visually.”

The audition won Norma Jeane a six-month contract. She was also given a new name. She and Lyon stitched together her mother’s maiden name (Norma Jeane’s suggestion) and the first name of actress Marilyn Miller (whom Lyon felt this aspirant starlet catted to mind).

And so it was, in a phrase Elton John would sing poignantly decades later, goodbye, Norma Jeane. And hello, Marilyn Monroe.

It is clear, in reviewing the tangled and often tormented early years of this woman, that none of the biography we have thus far recounted would be remembered by anyone today had this transformation not occurred. Who would have bothered to put the narrative together? She was thoroughly inconsequential. Just another unfortunate product of a brutally fractured home who was facing life without a high school degree and, barely 20, with a failed marriage.

But she had been found by Hollywood. She had been plucked; she had been chosen.

At the time, it surely looked like her salvation.

It is a quote. LIFE MAGAZINE JULY 2017