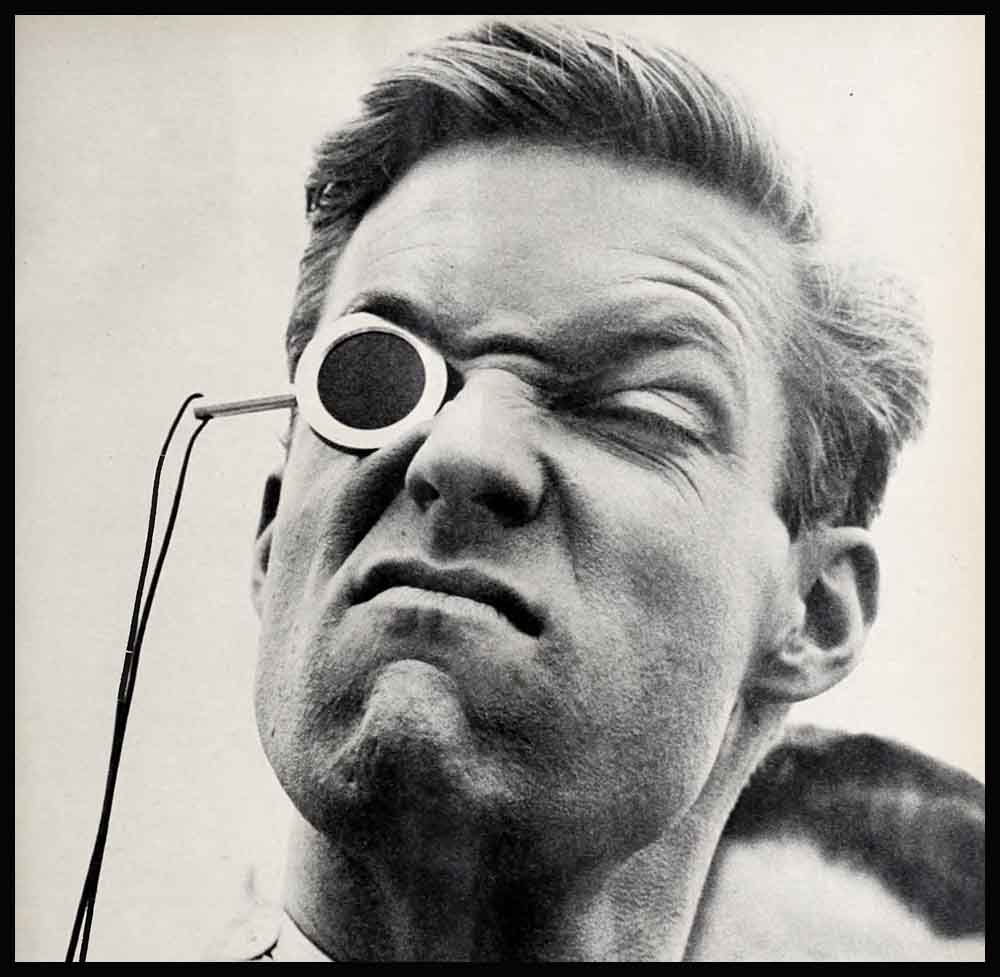

Richard Chamberlain Loves to Laugh

PART II

If Dick Chamberlain’s desire to become a star burned deeper than most kid’s it was also more carefully hidden. Hyper-sensitive, he didn’t want to get laughed at, either by the kids or at home. Today, Dick is different. He likes to laugh and to be laughed at—and even considers himself something of a comedian.

But at that time . . . it wasn’t giving anything away to head for the movies every Saturday. That was as natural to a Beverly Hills kid as it is for a country boy to head for the nearest creek. And so he kept his secret. He joined the bike brigade at the movie theater up the Street, with his pals from South Elm, by himself, or even with a girl, because Dickie Chamberlain always liked the girls and the girls liked him. He wooed them one at a time—as he does today—and he had his first “date” at six. He can’t remember her name but after her came Arden, the baby doll. Next Arlene, a brown haired pal girl who liked to play games, took over; in seventh grade it was June, who was a cute tease; and finally in eighth, Ann, more on the sweet side but of bittersweet memory to Dick. “I bought her a heart-shaped box of candy for Valentine’s Day,” he remembers. “But when I got up nerve enough to ring her door bell there was another boy already there—with a bigger box. He stayed. I crept home in humiliation and dismay. All that money wasted!”

AUDIO BOOK

Whether he sat with a sweetie or just by himself Dick Chamberlain never counted the fifteen cents he spent at the Saturday movies wasted. The kid shows were bargains. He could stare all day long as western after western reeled off, dipping back to the antique days of Ken Maynard and Tom Mix. Sometimes, he went in for cliff-hanging serials and horror epics. “There was one where a maniac went around blowing up buildings and murdering people en masse,” recalls Dick. “That was for me.” If the film got dull the kids took over. Squirt guns were unlimbered and the air was filled with popcorn boxes, tinfoil balls and paper gliders.

Dick knew that if he were up there on the screen such bored protests would never break loose, and he promised himself that in some comfortably remote future that’s exactly what would come about. Flushed with this anticipated triumph he entered a Hallowe’en costume contest at the Fox-Beverly theater. His mother spent a week fashioning a pirate’s costume and, when his turn came, Dickie trotted proudly out on the stage. There was a weak ripple of applause. He stood in the wings waiting hopefully as winners were announced. A boy from his school dressed patriotically as “Uncle Sam” got second prize. Dick got nothing. He dragged home, stunned and unbelieving.

“But, looking back,” says Dick, “maybe that was the challenge.”

If so, it lay unanswered for a good long time. Soon after, Dick Chamberlain -went on to Beverly Hills High and his world became crowded with other matters. He was fourteen but already six feet, one, “a deadpanned, skinny string-bean,” as Dick describes himself unglamorously, “with long, greasy blond hair.” As usual he figured himself a total loss in the wake of his big brother. As usual, Bill was long gone—to college—leaving his glorious record behind for Dick to buck. Bill had starred in football, basketball and track, was a social sensation with boys and especially girls. He was voted “Handsomest Man In School” at graduation.

Dick had no such great expectations. He tackled BHS with one resolve: “I wanted to go to college,” he says simply. “I knew college was important. I knew I’d have to get good grades to make it, so I worked.” Dick got the grades—a solid “B” average all four years. But success breeds success. once he got in the main groove, it was surprising how easily others opened up. By graduation Richard Chamberlain’s record was nothing to sniff at, even stacked up against his brother Bill’s.

He sprinted four years on the Varsity track team—100 and 220—and while he didn’t always win at the interscholastic meets he usually placed. He made the “Squires” a lower school service society, and the “Knights” that came after. He headed the Drama Club, was president of A.U.A. (Art, Understanding, Ability) ran the Student Court as “Chief Justice” and was a wheel in “Argonauts,” a VIP group.

Quiet authority

Still, as one classmate remembers, “You couldn’t say Dick Chamberlain was really terrifically popular at Beverly High. Respected is more like it. He was the kind you just naturally elected to offices and things. He had a sort of quiet authority.”

Dick himself recalls, “It was an awkward stage of my life and I was glad to get out of it. I was in lots of things but I was never an organization man. I just went through the motions. I liked dramatics and I liked art—I was most at home there—but that was really about all. Except, of course for the fun.”

He had that, but, as usual, in Dick Chamberlain’s own quiet, selective way. He showed up at the dances after basketball games in the big school gym, or at the country clubs scattered around where proms and class balls were held. But be was never the life of any big party. Bill Chamberlain’s wife, Pat, remembers that Dick, late in his teens. could come into a gathering at their house and be so quiet that you’d never notice he was there.

Dick was different around his own close set of pals—Dick Hall, Don Tinsley, Billy Ruggles, Vernon Lohr and Travis Reed and their steadies. Naturally Dick had one too. Donna was the kind of girl he always chose—pretty, peppy but femininely sweet. Usually somebody could promote a family car; and if there wasn’t a dance or a movie all wanted to see, they could always drive up into the hills, park and as Dick grins, “neck in the back seat.” But the most fun was roaring off to California’s handy mountains, desert or beach on weekends for picnics and sport. Dick liked the beach best because he’d figured a way to casually stroll off the public strand into the private Del Mar Club and blandly assume the privileges of a member. All it took was a cool head and a bit of acting.

That came naturally to Dick Chamberlain, so naturally, that he wonders now how he ever let his movie star dream slumber throughout high school. He did do a couple of scbool plays but something else seemed more his dish. Among the scores of forget-me-nots which classmates scribbled on Dick’s last copy of the Beverly High’s yearbook, “The Watchtower,” is one which explains: “To a wonderful guy,” it reads, “and a terrific artist.”

The same book summed Dick up in ways that hardly blocked out an actor’s essential ego. He was voted, “Most reserved . . . Most courteous . . . Most sophisticated.”

So, painting, Dick Chamberlain decided, was his major talent and il would be art he’d go after for his life’s work. In a way it was like track, the sport he always preferred to football. Basically, both were solitary and you won or lost by yourself. He liked that idea. After graduation, he enrolled at Pomona College, in Claremont, to major in art. That summer his mother inherited part of an oil well. “It pumped away faithfully all the time I was in college to put me through,” says Dick. “The minute I graduated it went dry.” Everything else flowed as pleasantly for “Chambo” Chamberlain during his dear old college days. He felt at home there as he had never felt before or, truthfully, since. “I loved Pomona,” Dick says simply. Other alumni have felt the same way. One loyal grad, Robert Taylor, was called “Pomona” by his first wife, Barbara Stanwyck, all the time they were married.

Claremont, which Californians call. “The Oxford of the West,” is only thirty-five miles from Beverly Hills. But, except for the mountain backdrop and sunshine it could be in another land. Four colleges cluster there—Pomona, Scripps College for Women, Claremont Men’s College and Harvey Mudd. Pomona’s buildings are classic and ivy clad; old trees shade its quad. There’s little rah-rah; the climate is academic. secluded and detached. In Dick’s day only 1100 hand-picked students roamed its halls.

All of them soon knew Chambo Chamberlain. From the start and in various ways, he was a marked man. At the big Frosh-Soph mudfight Dick had a heads-on collision with the Soph captain and broke that leader’s nose. “For some reason,” recalls Dick, “that made me a hero.” He went out for track and made the mile re* lay team. The Phi Delts took him in; so did the Scripps girls and Pomona co-eds, in strictly another way, as he passed with his golden good looks.

“Dick’s only problem was holding them off,” remembers Bob Towne. “More girls were after him than he knew what to do with. You couldn’t blame them. He was as good. maybe even better looking then than he is now. And, even in Levis and a T-shirt he always looked as if he had just stepped off Saville Row. I had early morning classes with Chambo and I never saw him with a hair out of place, a whisker or, for that matter, a smudge on his face.”

Spotlight

In one way or another the spotlight focussed on Dick Chamberlain all his four years at Pomona. If he wasn’t winning a trophy at an art exhibit, he was starred in a theatrical production. And sometimes, of course, the spotlight was there, but mercifully deflected by Dick’s misleading look of innocence. Like that outrageous poster on Carnegie Hall at the Arts Festival.

“It was a work of art,” declares Martin Green, who was in on the prank. “Not the painting—but Dick’s whole cool maneuver. It involved a brilliant plot—swiped fire ladders, split-second timing with the police, all night work and destroying the evidence. We hung it so high that it was two weeks before they could figure a way to get it down from there.”

The three stealthy operators—Dick, Martin and Dave Ossman—were all “DP’s.” That meant “Dramatic Productions,” although jealous outsiders had a less flattering name for the exclusive, elite group—“Displaced Persons.” As a member, strangely, that’s just about what Dick Chamberlain was.

His major was not dramatics but art. He loved it and was good. His paintings won prizes and he even sold some to Pomona students. “Dick had real talent, still has,” says Martin Green, who should know. “He could have been a fine painter, especially in ordered abstractions and geometrical subject matter. He was especially good in grays, blacks and whites.”

But Dick was a dedicated DP for two reasons: Although truly popular for the first time in his life, he still needed a close circle of kindred souls with whom he could shed his reserve and let himself go. As at Beverly High, Dick took in the school dances and events. But it was with Bob, Dave, Martin, Hal and their girls that he really had fun—up at “Stinky’s” joint in the canyon, on ski junkets to Mount Baldy, or at Stan Kornyn’s big home in Covina, where, after a show, they could keep a party going all night. fueled with gin or cheap champagne. DP was a true fraternity, not just a “social” one. Dick has always needed that.

The other reason was longer range and even deeper: As school slipped by, something was happening to Chambo Chamberlain and he knew it. “I was thinking less and less about painting and more and more about acting.” he says. In other words, that crazy kid dream was popping up again out of the past, despite himself.

“I think the turning point for Dick was when he d id Shaw’s ‘Arms and the Man,’ ” believes Bob Towne. “He did a brilliant job.”

Virginia Prince-House Allen, head of Pomona’s Drama Department, thought the same thing. “I’m considering trying to he an actor instead of a painter,” Dick told her. “Should I?

She thought a minute. Dick wasn’t majoring in her department. “Yes,” she said. “I think you should.”

It was too late by then to change his college course, but from then on Dick Chamberlain knew what he was after. He told Bob Towne flatly. “I’m going to act. It’s not such a lonesome life. Besides, I think that I can give more and get more.”

“I was amazed. really.” says Bob. “Dick was handsome, sure, talented, yes. But where was the conceit and the ego? I still don’t know.”

At any rate, when Dick Chamberlain stood in cap and gown at graduation in the spring of 1956, he had only one thought in mind—getting somewhere in Hollywood. For the first time in his lite, nothing, not even a girl, sidetracked that idea. Dick says he broke up with “Joan,” his steady of two years about that time when she got too serious. But none of his pals remembers a “Joan.” I think Dick s fudging,” says one. “But I’ll tell you a girl Dick was in love with—we all were. Her name was Nancy and she had everything: A cameo-cut face so beautiful it hurt you to look and a divine figure. A voice like an angel. She played the piano like a dream, painted beautifully, acted even better. But she gave only one of us more than a kind glance and that’s the guy she married. Dick called her, ‘The Goddess.’ ”

Maybe it’s just as well that Chambo didn’t score. Only four months after he drove home from Pomona with his sheepskin, the Army nabbed him.

That was a blow Dick hadn’t counted on and it chopped low. “It was painful enough to leave Pomona.” he remembers. “But then to get slugged with a ‘Greetings! ’ ”

It was only the beginning of two years which in Dick Chamberlain’s book. add up to one long, frustrated waste. Symbolic of his futility was the mural he painted in the dining hall at Fort Ord. where he went first for basic training.

It was a mighty project—18 feel high and 35 feet long and covered one whole wall—a wharf scene, because Ord’s beside Monterey Bay. Dick worked like a dog finishing it the final four weeks. Everyone from the C.O. on down patted him on the back. Again, Dick was in the spotlight; again, it meant nothing. “Right after I left.” he sighs, “the next C.O. ordered the whole thing painted out. No great loss, I suppose.” Perhaps, but still frustrating.

Private Chamberlain left for Seattle with the 32nd Infantry heading for occupation duty in Korea. Next a transport plane dumped him at Pusan and another dumped him at a place called Camp Hovey, 30 miles in from Seoul. It was Endsville in Bamboo Lane. “If there was anything around there worth seeing or doing I never discovered it,” says Dick. “The most uplifting activity was drinking beer. Even less exciting than the scenery or suds was Dick’s job—company clerk.

“I had to do all the paper work.” says Dick. “Morning reports, company correspondence, filing, personal cases, court-martial records and stuff. It took me eight months before I was really on lop of that job.” They rewarded him with a corporal’s stripes and finally a staff sergeant’s. Dick would have settled for his PFC without the headaches. Until “Dr. Kildare.” he says. “I had never worked so hard in my life.”

The only relief he had in fourteen months was a seven-day pass to Japan on the standard “R and R”—Rest and Relaxation. All Dick had lime to see was Tokyo, which is a sort of Oriental Los Angeles with kimonos and crazy neon lights. He stayed at a USO hotel, sat through Kabuki shows, peeked in at a few geisha tourist traps, fumbled through sukiyaki and tempura with chopsticks, prowled the Ginza and bought a couple of cameras. In one shop he also picked up one of those cute Japanese dolls, the live kind. She had an American name. “Toni” and spoke good English. “A lovely girl, all right,” allows Dick, “but it was hardly a romance. I wanted to see the inside of a Japanese home so I pestered her to take me to hers. She finally did, but I discovered her parents didn’t think much of the idea, or of GI’s. either. All in all. I didn’t have such a terrific lime in Japan—or anywhere else in the Army. I felt like I was just getting old and learning nothing. I wanted to get started, for God’s sake.”

Dick spent his final service weeks at Fort MacArthur, right out of Los Angeles. He itched so to get going in Hollywood that before they let him loose he rattled up there after duty, in a dinky Renault he bought for lessons with Carolyn Trojanowski and Jeff Corey. Then he was free at long last, but loaded with problems.

“Briefly, they were, no money, no place to live, no experience and no contacts.” sums up Dick. His first attempts to get all lour were pretty discouraging. For three months he lived at home, way down in Laguna Beach where his folks hall moved, but Dick soon discovered that Tom Wolfe was right: You can’t go home again. His family was sympathetic with his ambition but nobody exactly cheered. How could they? He was just one of a thousand others with the same long odds against him. “I didn’t want to take dough from my folks, but I did.” says Dick. “I had to have lessons and I had to eat.” He also had to pay $60 a month for a Hollywood pad in what Dick calls, “The Dismal Arms.” The years 1958-59 are not rose-tinted in Dick Chamberlains memory. They were the seasons of despair. Dick expresses it neatly: “There’s nothing so depressing as being on the outside of show business, trying to get in.” And that’s it.

Of course. it‘s also the oldest story in Hollywood. For the brash, the brassy, the thick-skinned, it can be an exciting game. But the sensitive suffer. Dick had never flailed helplessly at thin air before. Always some good things had come his way, whether he really enjoyed them or not. Now nothing, and nobody seemed to care. “I almost went out of my mind,” Dick admits.

He was only twenty-four but already he lived in a neighborhood of defeat. His apartment house was filled with old people who had long since had it. The hail was chronically posted with funeral notices. It was dismal cooking and eating his skimpy meals alone, standing in line to pick up an unemployment check, doing nothing most nights except study and read. Even the job he finally found attending the paralyzed woman, was not what you’d call cheerful.

“Still, I was lucky,” Dick Chamberlain believes today. “All that time I had very wise people keeping tab on me and cracking down.” Two were Carolyn Trojanowski and Jeff Corey. Low or not, Dick never stopped taking lessons. And they weren’t always encouraging.

Jeff Corey is a drama expert who has helped straighten out such stars as Tony Perkins, Gardner McKay, Diane Varsi and Tony Quinn. “The thing I liked about Chambo,” he says, “was his sensitivity and charm. He had a lot of good stuff. But he had done mostly classical things in college and was inclined to be too lyrical. It was hard to bring him down to earth. I used to tell him. ‘Dick. for Heavens sake, go out in the hack yard and rub some dirt on your face!’”

Corey put Dick in a class where the “climate was stressful.” Students there were trying to strip themselves down to their own raw juices. “It was painful for Dick.” recalls Corey. “His face turned red and he broke out in sweats. He wasn’t ready for that.” That was when Dick Chamberlain came close to quitting. Wisely, Corey put him in another class that was milder and he carried on. “But he was always shy.” concludes Corey, “and it’s too bad. There are a lot of wonderful things about Chambo that most people don’t get to see.”

For a long time few around Hollywood saw more than a handsome, mannerly, young man who’d like a job acting. Only the ones who got to know him became boosters. One was Lilie Messinger, former personnel assistant to Louis B. Mayer, late boss of MGM. A friend of Dick’s family sent him to Lilie, who’d “retired” and turned agent. In her day she’d helped hundreds of newcomers get started but now the last client she wanted was a raw unknown. “Things were too difficult in the industry.” she explains, “And I’d promised myself I’d never go through that again.” But when she met Dick, “He was so charming and attractive,” she says, “I couldn’t refuse.”

Wherever Lilie Messinger took Dick, however, others found refusals comparatively easy. Everybody liked him; nobody gave him a job. He was always, “Not quite right.”

Dick, however, takes some of the blame.

“I think it was largely my own fault,” says Dick today. “I froze up on interviews. When they asked me to read I got a block that reached clear hack to third grade. I couldn’t sell myself. They could see I was no professional, not yet anyway.”

“No. Dick wasn’t,” agrees Al Tresconi, MGM’s casting chief, who looked him over then, as he had even before at a Pomona College play. “But if you have it in the eyes—you have it. They tell the story. Put it this way: The first time I saw Dick Chamberlain I thought, If nothing else I’d like this boy to be a friend of mine,” Tresconi had nothing cooking then to put Dick Chamberlain in but he made a mental note: Good bet for a long term MGM contract.

That’s exactly what Dick finally got, of course, but not until his wide eyes had opened considerably wider by the hotfoots of show business. His very first “break” in a TV pilot for “You’re Only Young once,” turned into exactly one line which he delivered with three other people yelling “Goodbye” to a wedding party. There was a movie, too, “The Secret of the Purple Reef,” and again Dick’s hopes rocketed up only to descend with a thud when they scissored his part to nothing. Then Lilie Messinger went to work for a network—and now Dick had no agent. Now and then he managed to pick up some small TV spots on his own. in “Gunsmoke,” “Mister Lucky.” an Alfred Hitchcock, “Bourbon Street Beat.” “I got by,” he sums it up, “with an occasional loan from home, my chauffeur job and a work check now and then.” Was he discouraged? “It was scary at times, sure,” Dick allows calmly. “But I didn’t expect too much too soon. I knew what I was up against. It all depends on what you want and how badly you want it. I wanted it pretty badly. That’s why I never stopped those lessons. I realized I wouldn’t get steady work until I rated it. When I did rate it . . . well, the break came along.”

The break Dick means was when powerful MCA took him on as a client. A friend of his family’s, Jack Bailey (Mister “Queen For A Day”), aced him in there. As agents, MCA thought big and acted the same way. all through 1960. as MGM waded carefully into television, Dick Chamberlain knocked steadily at MGM’s door. He went there first to make a western pilot, “The Paradise Kid,” but in those days you couldn’t flip dials fast enough then to get away from new TV cowboys. It didn’t sell. Next Dick tried out for a tentative half hour version of “Dr. Kildare.” Nobody wanted it at first so that effort was dropped. He showed up again for another pilot, “Father of the Bride.” He wasn’t the type. Then “Dr. Kildare” came up again—a big hour show now with the works behind it. MCA shot Dick right out again. This time MGM invited him in to stay. That was December, 1960.

Of course, it wasn’t that simple. It never is. For a time both “Dr. Kildare” and Dick Chamberlain were on trial. Launching a major TV series is something like a blast off at Canaveral. If it goes into orbit, everybody’s a hero; if it fizzles, they come up bums. Dick knew that thirty-five other actors with far bigger “names” than his, which was minuscule, had tested for Jim Kildare. He also knew that one big reason he got it was because he came cheaper than most. The money wasn’t too important. but the opportunity was. It could be the beginning for him-—or possibly the end. The situation called for a Chamberlain speciality, control under pressure. And once again. Dick Chamberlain was where he seemed always to land—in the spotlight and yet all alone.

In this respect things cbanged hardly at all for Dick when Director Boris Sagal saw rushes of the first “Kildare” show, hustled up to the front office and told anxious MGM execs, “Stop Worrying!” Ulcers healed magically all over the lot. But for Dick it was different. He was on the spot. What his pal. Bob Towne, calls “Dick’s disciplined ambition” has yet to let him step off to relax and enjoy his good luck.

From the start Dick’s poker-mask has made it all look ridiculously easy. It never was. “The first year,” says a director who guided him often, “Dick Chamberlain got by mainly on his nerve and his good looks.” Raymond Massey adds benevolently, “Dick has grown an awful lot in this job.” But there’ve been growing pains, too. Most are connected with Dick’s period of adjustment to life as a public figure. Psychologically, he wasn’t cut out for that.

Secure on Stage 11 Dick is comfortable, as he always has been in a light little group who know him, work with him, have learned to like and understand him. “In fact,” says his makeup man, Jack Dusick, “sometimes you almost forget Dick’s around. Problems? Never. I just pat on some ‘pancake’ and Dick seldom looks in the mirror.” The other day. Bill Sargent, an actor friend of Dick’s with a small part, found himself without a light in his dressing room. Chambo noticed Bill struggling to dress in the dark, politely asked an electrician for a fixture then installed it himself, rather than make even a minor fuss. That’s typical of his setside ease. He’s a pleasure to work with.

Yet, barely a year ago, after Dick was interviewed on TV before a live audience of women, he stepped off the stage, clutched his stomach, and mumbled to Chuck Painter, “I think I’m going to be sick!” Last summer in New York he cautiously timed his arrivals at Broadway shows so that he could walk to his seat in the dark, and leave before the lights went up. “Dick’s improved. Now he’s more self confident in a crowd.” believes Painter. who is usually at his side. “But he doesn’t like to be ruffled—no surprises. Dick wants to be all set.’’

Last year when Lilie Messinger sold NBC on Arthur Freed’s TV spectacular. “Hollywood Melody.” she suggested Dick and got a yes. She called Dick late at night and told him the news. “Oh, my gosh!” he protested. “I don’t think I’m ready.”

Dick was ready enough to score a vocal hit in his live TV debut, singing “Manhattan’’ with Shirley Jones—as smooth as if he’d been doing that sort of thing all his life. But only his voice coach, Dick and a few people close to him know how he worked and worried every day until the show went on the air. One bunch was his “Kildare” crew. who sent him a gag wire to break the tension right before his number: “MY DADDY IS LETTING ME STAY UP LATE TONIGHT TO HEAR YOU SING, CAROLINE.” Someone else, even closer. knew about the lonely fights Dick Chamberlain stages with himself to come through cool, calm and perfect in a challenge like that.

“I knew Dick would be up to it. He”s up to anything,” says Clara Ray. “But my heart ached to be there backing him up.” Instead Clara was in Houston on a singing engagement. all she could do was send another wire: “GIVE ’EM BOTH BARRELS, SWEETIE.”

That’s precisely what Dick Chamberlain has been doing, of course, every since he started stalking an acting career in his solitary, bird dog way. The method’s hard to beat; nothing succeeds like success. Yet, some who know him well think it’s time Dick scattered his shots in other directions.

“Dick looks like a kid but he’s pushing thirty,” one points out. “School ought to be out for him now. He needs fun, a fling, some wild oats. It’s right here for him and he rates relaxation. He works hard enough on ‘Kildare.’ ”

“I can’t criticize Dick for pushing his break with self-improvement,” says another. “More power t o him. But if he doesn’t watch out, he’ll pass over some of the real things in life that make a man grow, too.”

But yet another disagrees vigorously. “Dick is having all the fun and living he needs but in his own way. Few people understand him. Basically Dick is an artist, also he’s intelligent. His tastes are sophisticated. They’re tied to art and culture as they have been ever since he began to grow up. Dick simply doesn’t enjoy the aimless socializing, party, nightclub and playboy swinging that attract most empty headed Hollywood bachelors who suddenly make it. It takes all kinds.”

Dick Chamberlain explains himself like this: “Right now it’s important to me to satisfy myself as an actor, a singer and an all around performer. I still take these lessons because I realized long ago that I’d never get what I wanted unless I did. After you go around for months without getting a job you tell yourself. ‘Wait a minute, something’s wrong!’ What was wrong with me was that I wasn’t worth anything to anyone, so nobody wanted me. I’ve been extremely lucky. My break at MGM came after a long fallow period. I’m grateful. But I wasn’t sure I wanted to do a TV series when I started. I know now I don’t want to do one forever, even if that were possible. The question with me is: After ‘Dr. Kildare,’ then what?

“I think I’ll end up on the stage,” Dick continues. “I’ve found I love it and I think my future’s there more than TV or even movies. So I’m preparing, that’s all. Sure, I like fun and people as well as the next guy. It’s a constant frustration with me not to be able to join in more. Only right now I simply don’t have the time.”

What free time Dick Chamberlain has he spends mostly with Clara Ray. He’s had other girls. Before Clara there was Vicki Thal, John Saxon’s ex-girl friend, whom Dick met in his dance class. He has also taken out Anne Helm and Joan Benny, among others. But Dick has always been a one girl at a time man and right now it’s Clara.

Clara Ray’s own career often takes her out of Hollywood singing on the hotel, fiesta and operetta circuits. But when she’s home “Clarie and Dickie,” as they call each other, make a duo. Sometimes Clara cooks Dick a steak at her tiny Hollywood apartment while he works up an appetite on her piano; other nights the same scene shifts to Dick’s hideaway. When they’re feeling grand they dress up and dine at Windsor House or Trader Vic’s for Dick’s favorite Polynesian food. once or twice they’ve shot the bankroll at the Beverly Hilton’s Escoffier Room, where you can get a modest little snack for about $25 a copy. Afterwards. if they aren’t due for a lesson or an MPT project, they like movies, off-Boulevard productions, or opera when it’s in town. On rare workless weekends, they usually head for the beach. Thursday nights. of course, TV is a must.

Clara always wears the diamond pendant Dick gave her even when she does a “Kildare” show. She gives him potted plants for his sun deck and on his last birthday, after much trial and error, baked Dick a big fudge-iced chocolate cake.

“I wanted it to he perfect.” sighs Clara. “I spent all day on it, put in a dozen eggs and two pounds of butter. But when I took it out of the oven right before the party it looked like an oversized pancake! It was so hard that I had to use both hands to cut it. I’d forgotten to sift the flour. But Dick actually ate a piece and said it was delicious. He must like me.”

Clara Ray can speak plainer than that. If she won’t, facts will: Clara is the kind of girl Dick Chamberlain has always fallen in love with—a bundle of femininity, smart. talented and loaded with personality. She’s twenty-four to Dick’s twenty-seven. They like the same things, have every interest in common. To Clara Dick is “A marvelous person, so dependable and sweet and we couldn’t have more fun together.” But when you mention marriage. she gazes demurely off into space. “Why,” she says innocently, “we’ve never had that on our minds at all!”

Dick’s more explicit: “Marriage? Lord no—not now,” he protests. “I want to be married someday, of course. I think that’s probably the greatest adventure of all—and the most ticklish. Too many people toss it away. I might if I married now. I’m just not ready yet. Say, when I’m about thirty-two.”

Dick’s brother. Bill, is just thirty-five. but as usual way ahead of him there. Bill and his pretty wife, Pat, have three handsome children, Carole, Bill, Jr., and Mike. Like all of Dick Chamberlain’s family, Bill and Pat keep resolutely out of Dick’s career, on the premise that it’s his private party. They don’t share in his publicity and refuse to talk about Dick. The only one who’s been curious enough to visit the “Dr. Kildare” set is his mother, still so pretty that Ray Massey mistook her for an actress. But a big “Welcome” is always out on the mats, both at Laguna Beach and Woodland Hills, where Bill lives. The Chamberlain brothers are closer now than they were as kids. Dick borrows family life mostly from Bill, Pat and the kids.

To “Uncle Dickie,” Bill and Pat’s children are “my kids.” Dick spoils them with presents and sneaks off to play with them when he gets a chance. He even keeps a pair of roller skates hanging in his kitchen, so he can race them on the sidewalk when he comes out, a stunt which has mixed social blessings for the junior Chamberlains. “There goes that Carole Chamberlain with her Uncle Dick,” sniffed a jealous miss from the Collier Street School the other day. “She thinks she’s pretty smart!” Last Christmas Dick took them with him aboard a float down Hollywood Boulevard’s Santa Claus Lane where they fell promptly to sleep. What the neighborhood kids thought of that is unrecorded.

If Dick Chamberlain does wait until he’s thirty-two to make a home and found his own family, with Clara Ray or anyone else, he runs the risk of missing out on a hunk of important living, which even the most glorious career might not make up for. By then, unless they run out of patients, “Dr. Kildare” might still be hogging the TV screen, or Dick Chamberlain might he the toast of Broadway. Either way, chances are he’ll be rich. Already Dick makes four times the $400 a week MGM paid when they signed him, plus his loot from recordings. This spring he’ll keep working straight through an eight weeks “Kildare” layoff to star in his first MGM movie. Any day, if he had time, he could take off for the big money singing at Las Vegas, or the prestige clubs and hotels all around the land. Not long ago Martin Green went to Vegas with Dick to catch Carol Burnett in her act. “When she came on Dick clutched the table as if struggling to hold himself back,” says Martin. “You could tell he was just dying to get up there.”

What he makes now Dick socks carefully away in a savings account. He took on a business manager the other day though he has no wheeler-dealer financial plans. “We’ll see.” he says cagily. “Frankly, I love money and I intend to save it and keep it.” Dick bought his car, a “second suit” and tuxedo with his first MGM paychecks, has banked most of them since. His only extravagances so far are Martin Green’s paintings. “Dick is always talking about buying a new car or a house,” says Clara Ray. “I don’t think he’ll do either soon. He’s cautious and intelligent about his money.”

The house is one thing, Dick admits, “I want very much. I’d like to find a lot high in the hills with a wonderful view,” and build a place to suit my own needs. Then,” he grins. “I d really be on top of the world.”

But it could be, too, by that time, he’d add up to a crusty old bachelor still looking for the real Dick Chamberlain to step forward. For, Dick faces the trap most super serious actors face: all art and no reality can come up artificiality. And so far, Dick’s Street is distressingly one-way. “More than anyone I know,” says a close friend. “Dick needs the anchor of a wife. the stability of a home, a family.”

If Dr. Kildare could prescribe for Dick Chamberlain, a wife might be just what he’d order. Not only to banish the essential loneliness Dick has known all his life, but to dispel his fears and crack the bland, boyish mask he wears for the world. It still hides the fascinating man underneath, still makes Dick Chamberlain seem to most people what he is not. For it is the mask—and the mask alone—that keeps people from knowing how much more than a boy he is.

Only the other day, dressed in T-shirt and jeans, Dick wandered into a Laguna Beach drugstore, riffled through the magazine rack and came up with a ‘’Dr. Kildare” comic book. He moseyed over to the counter to pay.

The cashier looked at the comic book and then up and down at big Dick. “That’ll be ten cents,” she stated.

He gave her the dime and waited silently while she dropped it into the till. “Thank you,” she said “—little boy.”

—KIRTLEY BASKETTE

Dick’s on “Dr. Kildare” NBC-TV. Thursdays 8:30-9:30 P.M. EDT and is starring in MGM’s new movie “Twilight of Honor.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1963

AUDIO BOOK