Eddie Fisher Faces Losing Daughter

This is a story about three trouble-weary grown ups and one little girl, a story of two men struggling to fin and vin their rightful places in the child’s heart, the story of a woman, a mother, trying valiantly to walk the thin line of justice, realizing deep in her heart that in the battle between her husband and the man who was her first love, there can be no victor.

There can be only a small, innocent victim.

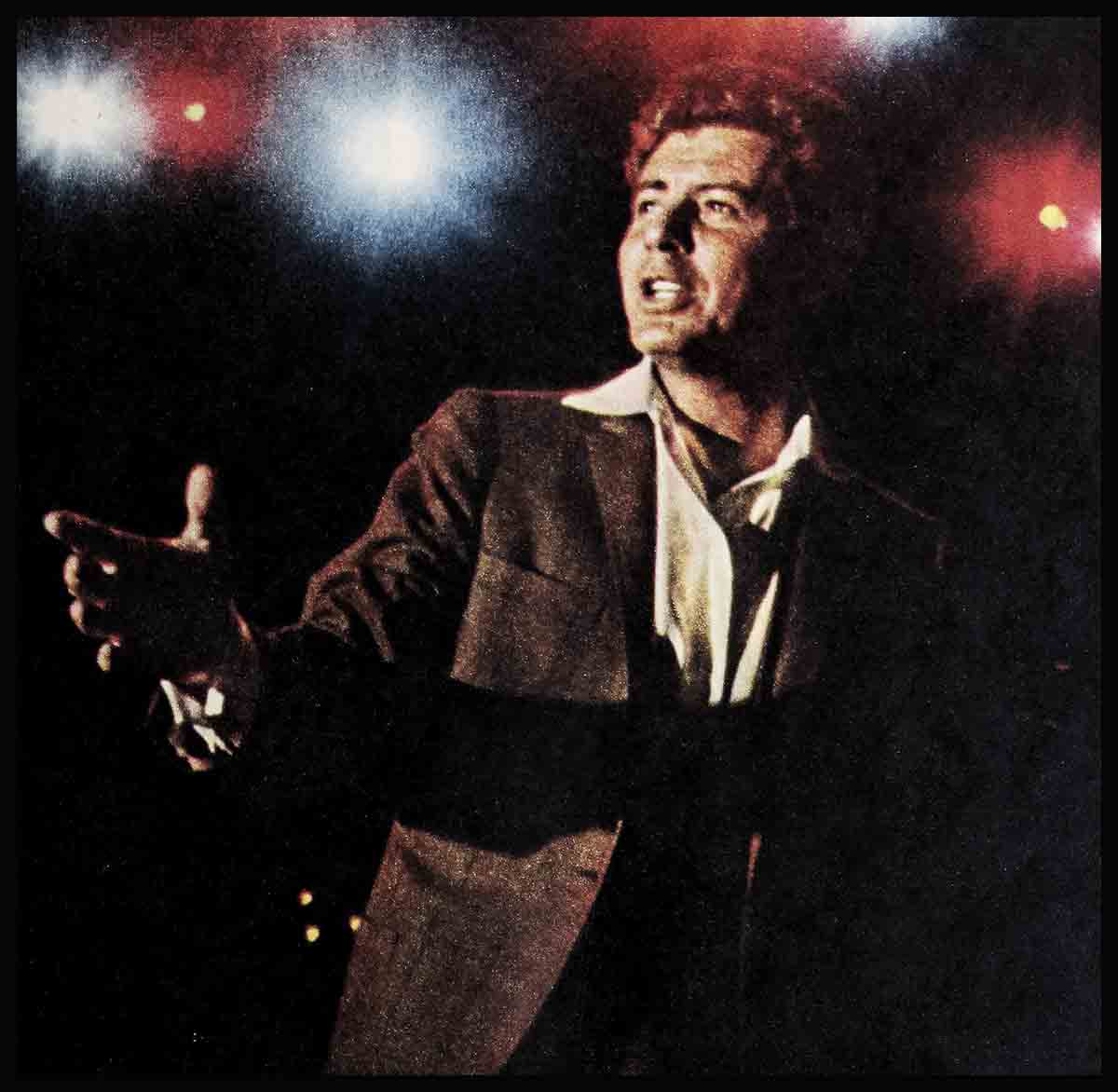

Eddie Fisher—whose daughter is all he has in the world, but who can never truly be her father—is a lonely man who knows that he must forge, in snatched moments of time, bonds of love strong enough to survive the day when Carrie learns the hard truth: that when he turned his back on her mother, he walked out on her.

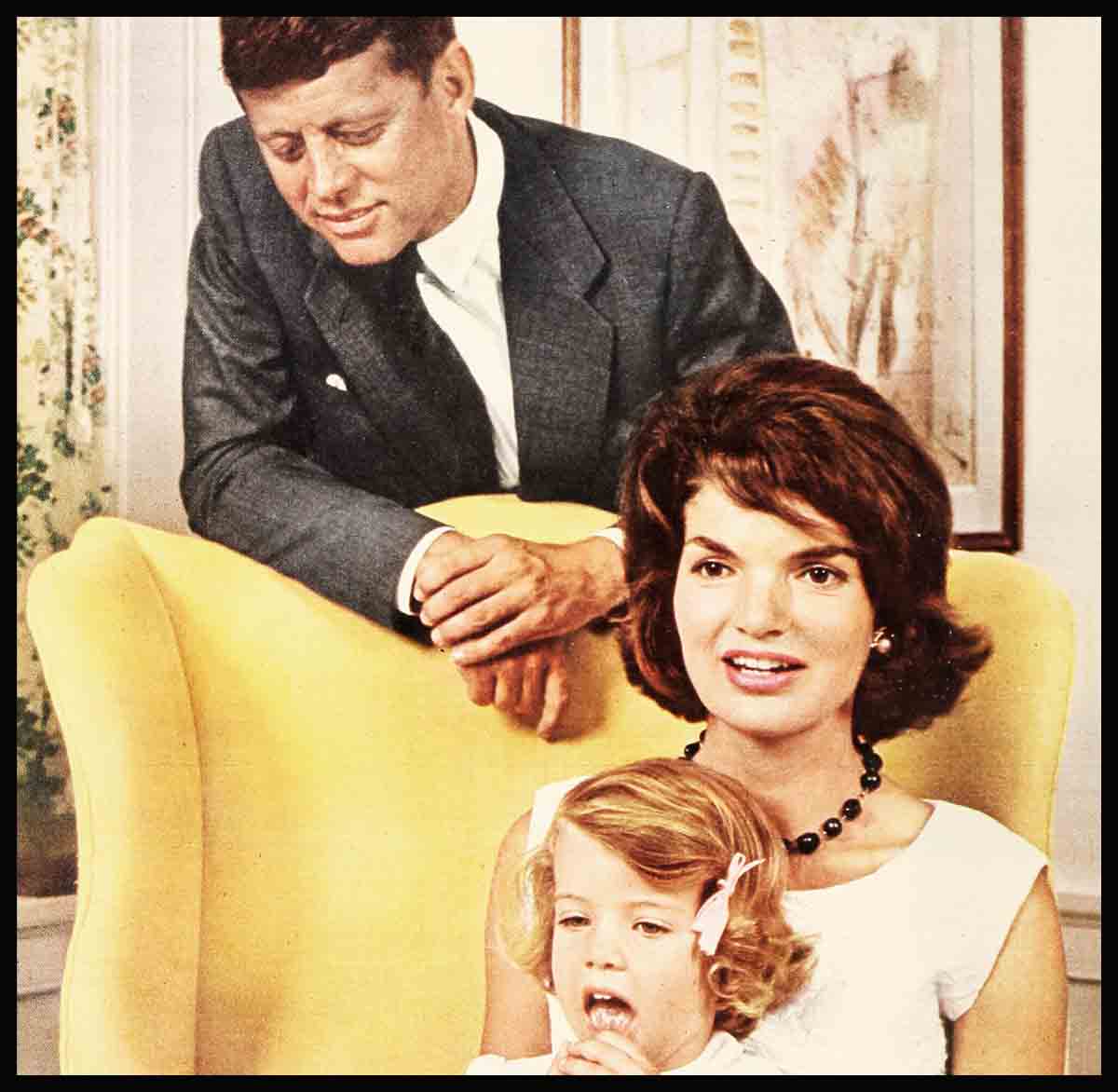

And there is Harry Karl—who filled the place Eddie vacated. Harry the head-of-the-house, the provider, the everyday father of a daughter not of his own blood. Harry who cannot help but sense that his hard-earned place in her heart is being threatened by Eddie Fisher’s unsettling presence in young Carrie’s life.

Carrie’s tragedy

And, of course, there is Debbie Reynolds, no contestant for her daughter’s love—for she knows she has that forever—but torn by the hidden conflict that rages about her. Debbie Reynolds who cannot avoid asking herself if, despite the promptings of conscience and generosity, she was wise to allow Eddie Fisher a place in her children’s—and there are two children—lives at all.

The children, Carrie and Todd, are too young to sense the danger, too inexperienced to know the peril of taking sides, too innocent to understand the complex yearnings and agonies of the human heart. Yet this story of the struggle for their love is their story. It could be their tragedy.

Eddie loves both his children and longs for them both to love him. But he cannot help but love them differently. His son will one day become a man, will have a wife and a family of his own. He must learn how to take care of himself. But his daughter will always be his little girl—no matter how she grows or how many children she might someday have. She has to be protected.

She is the something sweet of all his boyhood memories. She is the girl Debbie used to be when Eddie’s love for her was strongest. In a way, in fact, she is a little bit of every woman he ever loved.

And this is the child he is in danger of losing . . .

But let us begin by saying that it is a battle—and a strange one—no blows have been struck, no angry words as yet exchanged. Indeed. Eddie and Harry are not basically fighters at all; neither has a taste for conflict. For two years they have actually joined with Debbie in doing everything possible to avoid a struggle. Harry has taken great pains never to intrude upon Eddie’s precious visits with his children, never to hint to Carrie and Todd that Eddie has ever been anything but the most faithful and loving of fathers. Eddie has never allowed himself to try to enlist Carrie or Todd on his side in any dispute with Debbie and Harry over their upbringing—not even when Debbie told him she had decided not to keep her promise to raise Todd in his father’s faith.

And yet the struggle is taking place.

How can it exist between two men so determined not to fight?

Sometimes the crucial skirmishes are fought entirely without their knowledge.

Eddie never scolds

Say, for example, that it is Friday night in the Karl household. Harry comes home from his office tired, perhaps irritable. Business problems sometimes plague even a successful man. He joins the children at their dinner, and observes that Todd is pushing his vegetables messily around his plate, spilling his cup of milk onto the table. Harry, as he has done a hundred times—as every parent must—scolds the boy gently. “If you don’t want your food, son, you don’t have to eat it—but you know you mustn’t play with it that way.”

After supper Harry is a little too weary for a protracted romp with the children. Carrie gets only one story read to her instead of two or three. The same thing happens in a million households across the country—fathers have a right to be tired, and children must learn that their own desires cannot always come first. But Eddie comes to take the children out the next day. And Eddie, for the simple reason that he sees them seldom and only when he can devote himself entirely to them, is never too tired or irritable for them. Eddie has no need to scold he acknowledges the fact that discipline is no longer his job. “I’m the ice-cream-and-candy man,” he says—and why not? He isn’t with the children enough to spoil them.

But Eddie can lose, too. It can happen on a day when Carrie comes home from an afternoon with her best friend Gregg Champion (Marge and Gower’s little boy), carrying in her small hand a crayoned picture of a cat. She has made it for Eddie, has laboriously scrawled “Love from Carrie” in big letters across the bottom. A gift of love for her father. But her father is not there. Eddie is working in Las Vegas—it could be three weeks before his schedule allows him another visit with his children. Debbie explains this carefully to Carrie. But children are not content with the logic of adults. Carrie is hurt—Daddy should have been there to receive her offering.

That night when Harry comes home, she runs to him. “You’re my daddy, aren’t you?” she cries. Harry has no idea of what happened. “Sure I am, sweetheart,” he says, swinging her up in his arms, kissing her warmly. Soon the picture is tucked away in his briefcase to be taken to the office tomorrow, displayed with the fatherly pride Harry wears like a halo when he talks of his kids. And Carrie goes to bed content, Eddie forgotten.

Sometimes a hint of the struggle comes to each man.

Eddie, thumbing through a magazine, may come across an article that rehearses, in every sordid detail, the story of his breakup with Debbie, his ill-fated marriage to Elizabeth Taylor. For a moment his blood runs cold. Carrie is six; she can read now. Todd will soon be learning. How long before such stories are thrust upon them by other children, children who can only guess at how much the truth will hurt? What will Carrie and Todd think of him then? Will they turn from him entirely—will he lose their love, their trust? No, he tells himself, of course he wont. They’ll love him. They’ll love him enough to understand. But will they? When was the last time he saw them? Did they really enjoy themselves, or were they only being polite? Do they forget him entirely between visits, resent the fact that he is not there to bandage a cut knee, admire Todd’s skill on roller skates or Carrie’s new dress? Does Harry do such a good job of fathering them that they never think of Eddie—except as a sort of Favorite Uncle? What man can, with such chilling thoughts racing through his mind, resist the temptation to rush to a telephone, to call his children, to tell them of some spectacular plan he has for their next meeting—something that, perhaps, in his secret heart, he hopes Harry never thought of— something so wonderful that the children won’t forget it—or him—for weeks to come.

Harry’s fears

And Harry, after the children have been with Eddie, cannot always blind himself to the implications of Todd’s glowing face and Carrie’s obvious rapture. What Eddie bought them . . . what Eddie fed them . . . what Eddie said to them . . . all this the children pour out to Harry in innocent delight. And that, of course, is how Harry wants it; he would die before letting them guess that he and Eddie are not the closest, the best of friends. But he can’t help worrying. He rarely sees his own four children; he and Debbie lost their first baby, and though they are having another, Carrie and Todd are still Harry’s family. He loves them, he needs them. And like Eddie, Harry knows that he must forge unbreakable bonds now between himself and the children. He would be less than human if, after hearing them sing Eddie’s praises, he never thought: There’s that tricycle Todd wants—I was going to wait for his birth- day, but maybe I’ll get it for him now. If I don’t he might ask Eddie for it. And it’s not good for the kids to depend too much on Eddie’s generosity—after all, they do live here, with me—isn’t it better for them to be happy with this arrangement?

Natural thoughts. But dangerous ones. It does not take much to subtly alter the atmosphere around a child, and children quickly grasp the possibility of playing off one grownup against another. And when that happens, even though the child feels triumphant at being able to manipulate his elders—the solid basis of his security crumbles before his eyes, leaving him terrified by his own power.

Harry Karl and Eddie Fisher understand this all too well. Each of them has had first-hand experience in a complicated family situation. Eddie himself was raised in a broken home and can remember what it felt like to be torn between a real father and a stepfather. He has played the role of stepfather to Liz Taylor’s two boys, and had to share their love with their real father, Michael Wilding. Harry, separated by divorce from his own children, knows only too well the frustrated longings of a father who has lost his family.

It is vastly ironic that Fate should have chosen these two men to be opponents in such a struggle.

Is it possible to predict the outcome? Will one man or the other emerge the winner? Whose “brand” of love will the children prefer?

At the moment, Eddie has a lot going for him. He is the “ice-cream-and-cake man” and children are known to prefer ice cream and cake to meat and vegetables. There is glamour to Eddie, and mystery and excitement which the children cannot feel for Harry, who has become as familiar to them as the walls of their nursery. In the years ahead, as Carrie and Todd go through the normally turbulent adolescent period, Eddie’s very separateness from their every day existence may bring them closer to him. Eddie’s uncomplicated love for them may seem a kind of peaceful refuge from the conflicts that necessarily occur between adults and growing children.

Paddy Santa Claus

And yet, in the final analysis, if the children must ever choose between the two fathers, Harry must inevitably be their choice. For though Eddie is a kind of Santa Claus, a jovial occasional companion, Harry is part of the fabric of their lives; his personality, his virtues—even his faults—are woven into Carrie and Todd’s existence as Eddie’s will never be.

Even the matter of discipline, which may now cause the children to resent Harry from time to time, will in the end operate to his advantage. Psychologists tell us that one of childhood’s most basic needs is for someone to draw a line and say, “Past this, you may not go.” The child may rage and storm—but instinctively he knows that discipline is the ultimate sign of love and protection, that without discipline he is lost in the awesome world of adult responsibility. Someday Carrie and Todd will clearly see that in supplying a strong, steady influence in their early years, Harry was fulfilling one of their deepest needs—while Eddie, in his position as an outsider, could only caress the surface of their childish desires.

But in this story of human conflict, it is not only the victor who is important—but think of the victims. For the conflict that surrounds Carrie and Todd is fraught with dangers.

According to Dr. Tom Noyes (a New York psychotherapist and marriage counselor) : “When the relationship between the adults in such cases becomes one of a war for the children’s hearts, the children can become terribly confused and frightened. Even simple, innocent-seeming incidents can affect their emotional stability. If, for example, the divorced father, in his attempt to win their love, constantly takes them on joy-rides, on exciting excursions which wise parents offer only rarely—if he brings them into contact with groups of unfamiliar adults ‘to whom he proudly shows them off, surrounding them with attention and praise—all this can combine to give the child’s ego a kind of flattery it cannot get elsewhere. His home, the affection of his mother and stepfather can seem dull and unimportant by comparison.

Special complications

“I have known cases where such over-attention ruined an entire life—where the child grew up unable to be satisfied with the normal ego-gratifications that life provides, and went on seeking what he could never recapture, that magical moment in childhood when the whole world seemed to revolve around him. When this kind of situation threatens a child’s development, the only hope is that the mother can remain very strong, very stable, and give the child a normal atmosphere in which to grow.”

And if this is the danger in such a situation, how much more complicated does it become when a father feels about a daughter as Eddie does about Carrie?

This then is Debbie’s mission: She has to protect her children—especially Carrie. It is made more difficult because Debbie herself has mixed feelings about Eddie and his place in her and her family’s lives. She revealed some of her inner turmoil in her recent book, “If I Knew Then,” when she offered advice to a newly-married woman who was troubled about her first husband.

“Perhaps” (Debbie wrote) “you have some special feeling toward your former husband because he was your first love. But you must forget that and remember the hurt and humiliation he caused by deserting you.

“He’s a loser. Stick with the winner.”

Under these circumstances, it is hard to see how Debbie can fail to occasionally ask herself why she must continue to encourage her children to see and love Eddie. Wouldn’t it be better if Harry were their only father? Wouldn’t life be easier—and the children’s emotional well-being more secure—if Eddie were out of their lives completely?

So far, Debbie has managed to banish such thoughts from her mind. Graciously, compassionately, she has recognized that Eddie is tied to Carrie—and Todd—by more than blood, that he loves and needs them, and deserves a place in their affections. But if the day should ever come when Carrie and Todd are badly hurt, confused by conflicting loyalties—Debbie will have to do everything in her power to shield them from further harm, no matter who else is hurt in the process.

The Bible tells of a judgment rendered by Solomon, the wisest of kings. Two women came before him, each claiming she was the rightful mother of the same baby. Solomon, unable to learn the truth, commanded that a sword be brought and the baby divided equally between the two women. One woman quickly agreed. The other cried out—“No, give her the child, but let the baby live!” And Solomon in his wisdom awarded the child to the woman who was willing to sacrifice her role as mother in return for the baby’s life.

For Carrie and Todd Fisher, babes also, there is no such simple, clever solution. There is no “right” father for them. For good or evil, there are and will always be two men who claim their hearts—two men who love them as fathers love children, two men whom they must love in return. But whether this double burden of love, given and received, will strengthen or destroy them, whether they will end up as pathetic victims of a world they never made, whether Eddie is doomed to lose his daughter . . .

Even Solomon, in all his wisdom, could not know.

—LESLIE VALENTINE

See Debbie in MGM’s “How The West Was Won;” and “My Six Loves,” for Paramount and “Mary, Mary,” for Warner Brothers. Eddie sings on Ramord Records.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1963

zoritoler imol

1 Ağustos 2023Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was searching for!