My Nephew Bob Hope

It was forty-one years ago, and yet I remember, as though it were . yesterday, that wonderful morning when my sister-in-law, Avis Hope, arrived in Cleveland, Ohio, from England, together with her six sons.

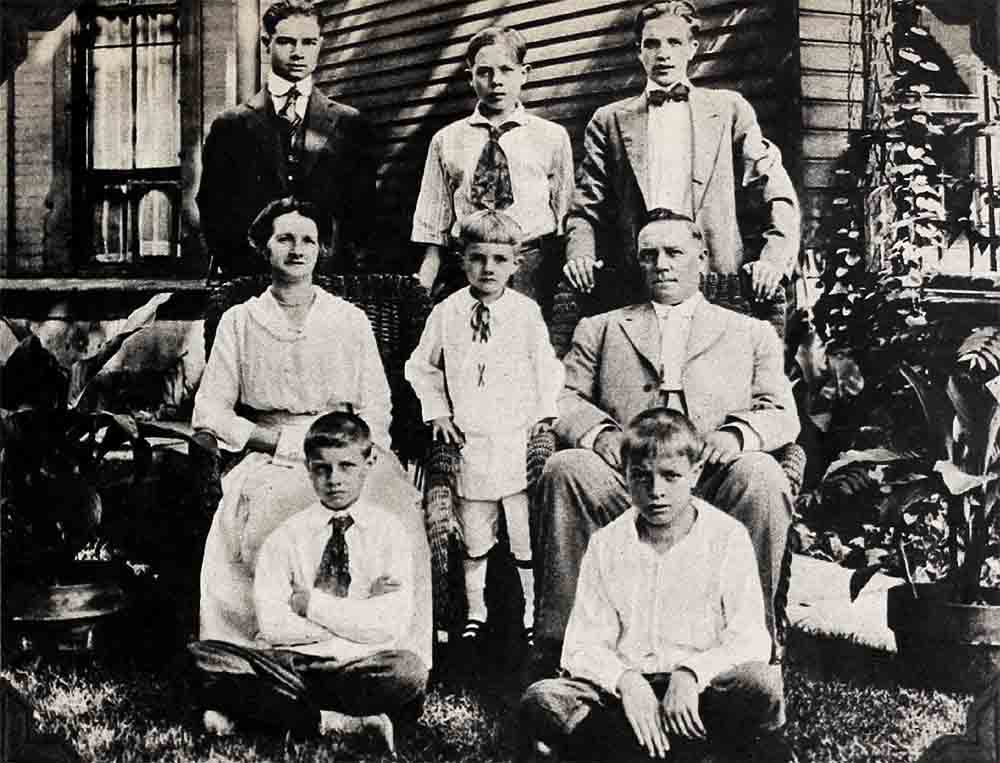

In the order of their ages they were, those little boys in their Eton jackets with their spotless white collars, highly polished shoes and perfectly combed hair: Ivor, Jim, Fred, Jack, Les and Syd. As the busy mother of three boys of my own, I definitely didn’t know which of my small nephews was which. Certainly, in my wildest dreams, I never imagined that one day I would be known as “Aunt Alice of El Segundo” to hundreds of people I’ve never met, all because of the particular boy the family called Les, but whom the world today calls Bob. Bob Hope, one of the finest men who ever came to fame, who was then barely five years old.

Yes, I call him Bob now, too, like the rest of the universe. He lives in a glittering world, quite apart from my simple world in a small California city. Yet he hasn’t really changed.

He still has many of the friends he made in boyhood. The first girl he ever seriously dated he still calls upon when he’s back in Cleveland, though she is long since married and the mother of children. The only girl he ever loved, he’s still married to, after seventeen happy years. His house overruns with youngsters and he loves them all, because he always did love a big family and being part of a gang.

I’ve seen him under all sorts of circumstances, when he’s been surrounded by a big pack of back-slappers or when he’s alone with myself and his uncle Fred. He’s always just himself. I could pay him endless tributes, but I guess the one that tells you most about him is that his entire family adores him. You know that’s unusual. It’s because he has always been so warmhearted, so thoroughly thoughtful and kind, we couldn’t do anything but love him.

But, let me go back to those early Cleveland days and tell you how such a fine man came to be. First of all, don’t misunderstand me. Superior as Bob is, he’s no better a man than his brothers. They have all turned out to be great men.

Bob’s father was my husband’s brother, Harry. Harry was a stonemason by trade, and so good at it, he used to cut the intricate stone framework for the rose windows in English churches. I guess it was my husband’s and my coming to America, and writing so glowingly about it, that finally persuaded Harry to come here, too. He joined us in Cleveland, got himself a stonemason’s job, and after eight lonely months, he had money enough to pay the passage for Avis and the six little boys. (A new baby, George, arrived a year or so after they got to this country.)

They stayed with Fred and me about eight weeks, until they could find a house quite near us, and they hadn’t been with us more than a week before I knew, busy as I was, cooking and cleaning and looking after my own brood, that the boy, Les, was the ringleader in everything.

He was never a bad boy. Avis wouldn’t have stood for that for one instant. Every boy had certain duties he was made to perform and if he didn’t, he got switched. Avis never had one boy just do one thing and another do exclusively something else. Each boy knew how to do everything, and to do it correctly.

As I said, Harry was an expert stonemason, but the wages for a job like that are never large, and nine mouths to feed is really something. Add to that, the way boys grow out of their clothes, and you see the struggle Avis and Harry had.

But Bob, as natural ringleader, found faster ways of making real cash money than just taking some two-bit job. He did sell papers, for years, at the corner of 105th and Euclid Street in Cleveland. He learned an important lesson in economics there, too, from John D. Rockefeller Sr.

Papers, at that time, cost a penny. Bob soon grew to recognize the elderly gentleman who drove by his corner daily, in a Phaeton with a chauffeur, and he would always have the paper ready for him. The old gentleman always had his cent ready, except this one time, when he had a nickel.

Bob didn’t have any change. He definitely didn’t know the man’s name, but he said, “I’ll trust you, sir. You can pay me tomorrow.”

“No,” said Mr. Rockefeller. “You go get me the change.”

Now, in Cleveland in those days, any sort of big store made change by putting the bill or coin into a kind of basket that scooted all over the store before it returned to you. For such a small bit of change-making, they made Bob walk back to the change department. It was about a block. It took time, but there was nothing else for him to do, so he did it, duly bringing back the four pennies.

Said Mr. Rockefeller, “See? Never give credit when you can get cash.”

It wasn’t until his Phaeton had gone on that a passer-by told Bob who the man was. Irritated as my nephew was, he didn’t forget that lesson. He is one of the most generous of human beings, not only with his money, but with his time and talents. But, maybe the fact that Bob never goes into debt, has something to do with this episode.

Still, Bob soon discovered he could make money faster by being funny. Avis told me he had accidentally discovered that in England, while he was still a mere baby. His great-aunt Polly, who was the widow of a sea captain, was crazy about him, and while he was still toddling, he found out that if he stuck out his stomach and showed off before her, she’d give him cookies.

By the time he was in his early teens, he translated this impulse by going into Charlie Chaplin contests.

Chaplin contests were being given everywhere when Bob was growing up, and he got so good that he used to go to Cleveland’s Luna Park for them.

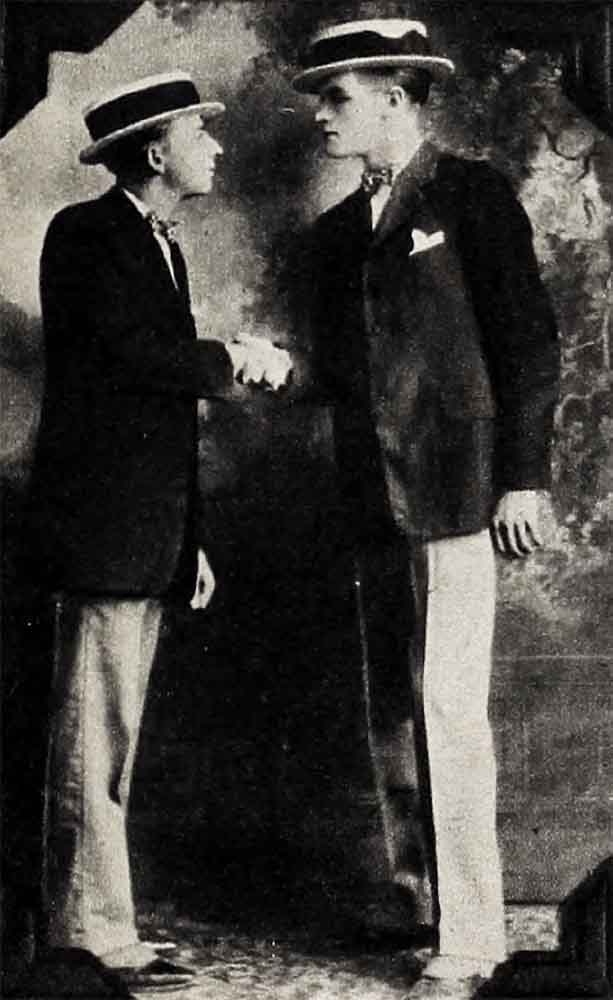

He was around fourteen when he met Charlie Cooley. All the Hope brothers palled around with Charlie, who went to school with them.

Charlie loved the stage and went into vaudeville while my nephews were still thinking in terms of high school. He did all right, too, so much all right that several years later, when Bob was trying to break in his act as a “single” in Chicago, it was his looking up Charlie that kept him from just plain starving. Charlie financed him, fed him, and got him booked in a theater for a weekend. Instead, they kept Bob for twenty-two straight weeks. That engagement was the turning point in his career.

Being the fellow he is, Bob didn’t forget. Today, Charlie Cooley works for him, and they are still just as close friends as they were as boys in Cleveland.

Bob and Dolores were married in 1932, and if there ever was an ambassador of good will, that lovely girl is surely it. After my husband died, his brother Frank and I used to call often on Bob and Dolores after they finally settled in Hollywood.

Frank and I both know they live in a world apart when they are in public, but at home they are still the unaffected, warm, generous people everyone loves. They took Frank and me back to England with them in 1939, and we would have stayed there, except for the coming war. It’s a rare Thanksgiving Day we aren’t with them, and most Christmases, and there has never been any Christmas or Easter that they have not most generously remembered us.

He’s famous, of course, for his talent as a comedian, as, for instance, in his wonderfully funny role in “The Great Lover.” But to me, he’s something greater than this, he’s a kind and generous man with warmth and a gift for friendship—my nephew, Bob Hope.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1950