JFK Came To Our Prom

For obvious reasons, I can’t reveal my name. You may not understand this now, but you will by the time you’ve read my story. Just let me begin by saying that sometimes my father gives me a swift pain. Like yesterday at breakfast. He finally came out from behind his paper and fixed me with his special, patented “we-didn’t-act-like-this-when-I-was-young” look. So I said quickly, “I gotta cut out for the library, Dad, they’re sure piling on the assignments early, I’ll say. . . .” I’m a college man. First semester. But my dad doesn’t get all that impressed. He cut me off with the “hrrumph” noise in his throat that means a lecture is on the way.

“High school students are the same everywhere. Unruly. Ill-mannered. Bad,” he said. (I muffled a groan in my napkin.) “Look at this—” he rattled the paper. “Thousands of them attacked the President. Kennedy.”

“Attacked?” I echoed, skeptically.

“Attacked! Listen!”—and he read from the paper: “ ‘President Kennedy lost his breast-pocket handkerchief and a PT-boat tie clasp today when he was mobbed on the White House lawn by 2.560 jostling and elbowing foreign students.’

They didn’t behave!

“Wait,” he said, seeing how I was shaking my head, “there’s more. Mr. Kennedy took a severe buffeting as the youngsters pushed and shoved to get to his side after clambering over and around rope barriers. . . . A boy snatched Kennedy’s tie clasp, and a girl got his handkerchief. “That’s two from our bus that got something,” one girl proudly exclaimed. . . . They plowed into Kennedy’s prized boxwood hedges, and threatened the flowers and blue-grass lawn of the garden adjoining the area. The police even had to line up on the porch outside Kennedy’s office to prevent the students from pushing through to the forbidden area.’ ”

There was more. Much more. And as he read on, my father sounded like a judge indicting all kids everywhere.

I wanted to tell him that it hadn’t been like that with us—with the kids back at John Burroughs High School in Burbank. California; that instead of protecting President Kennedy from us, the Secret Service guys had brought him to us; that instead of swiping souvenirs from him, we had presented one to him. But my dad took a quick look at his watch, grabbed his briefcase and took off. grumbling back at me. “They have no respect for private property—and they steal—and they have the nerve to attack the Chief Executive.”

Then he was gone.

I didn’t go to the library—it had only been an excuse to get away from my old man’s sermon, and it hadn’t worked, anyway. What I did was go up to my room and get down the box of junk in which I save stuff from high school. I spread everything out on my bed. There was one manilla folder with a sticker. “Senior Prom—June 7, 1963.” on it. From this I took out the prom program, a copy of The Senior Smoke Signal (our high school paper), some copies of The Burbank Daily Review, lots of clippings from other newspapers, a photograph that my girl had taken at the prom with a box camera with flash attachment that I’d given her last Christmas, and a handkerchief with some lipstick on it. (My girl’s handkerchief, not Kennedy’s.)

To be honest with you. I guess my dad’s tirade had given me an excuse to be kind of sentimental and nostalgic. For the next couple of hours I was back in high school, reliving one night I’ll never forget. And remembering the important things that led up to it. . . .

It started with no big deal, just an ordinary advance reservation made by our class officers to hold our senior prom in the grand ballroom of the Beverly Hilton Hotel in L.A. That reservation was made back in June of 1962, a whole year ahead of time, and in February, 1963, we began to work out our detailed plans for the dance. There were programs to print, tickets to sell, the band to hire—we decided on Al Hibler’s, a real jumping combo—and stuff like that. Everything was pure, smooth vanilla until April 22. Then the whole bit melted and got all sticky.

That’s when Mr. Paul, he’s the banquet manager at the Beverly Hilton, called up Mr. Weybright. he’s our principal, and told him the whole deal was off and we’d have to find another place to hold our prom. Mr. Weybright passed the had word on to Mrs. Elizabeth Hill, she’s the student government adviser, and in turn she told Tom Giuffrida, our class president. Tom then dropped the bomb on the rest of us.

It seemed that the California Democrats were holding a $1000-a-couple fund-raising dinner that same night. And when it was announced that President Kennedy would make a personal appearance at the affair, tickets started selling so fast that they had to switch to a larger hall. In fact, to our hall. They were in and we were out—in the cold.

I guess I don’t have to tell you how shocked we were. It’s like—like if a singer is booked into the Hollywood Bowl, and just before she’s to go on, is told that the concert’s gotta be held someplace else. Like maybe a banquet hall over a poolroom. You know the kind of feeling. . . .

Shock—then action

We flailed around. There was some further discussion with the Hilton people. There was talk of contacting some influential people who might help us. Our school paper printed an article telling how we got “bumped” out of the ballroom. And our local paper. The Burbank Daily Review, got wind of the story and gave it good coverage.

But soon our resentment simmered down. Rick Holbrook, he was vice-president of our class, spoke for all of us when he said we recognized the fact that Kennedy was the President and he should come first before 500 high school seniors.

But what all of us underestimated was the power of the press. The wire services picked up the story from our local paper, and then everybody knew about it. We had interviews and everything. One of the newspaper men raised our hopes—just when we’d got used to the idea that we’d have to find another place—when he said, “If Kennedy knew about this, I bet he’d do everything to help you guys.”

Not that everyone was rooting for us. For every letter or comment wishing us good luck, there was another calling us little brats and such. A lot of people felt we were forcing the issue, playing it up. which we weren’t.

But somehow, the optimism of the newspaper guys was catching. So the more than 500 fellows and gals in our class—and our teachers and parents, too—kept their fingers crossed.

And then it happened!

I don’t know who learned about it first—maybe it was Tom Giuffrida who heard the report on his radio right after President Kennedy’s press conference—but in just one hour we all got the message. And by supper time the whole town was celebrating, just as if our football team had won its last game of the year, making it a perfect no-loss season.

What happened was that Mr. Kennedy was asked by a reporter in Washington about (he prom situation. The President explained that California Democratic party big-shots had bumped us out of the Hilton ballroom without his knowledge, and he declared. “I just heard about it a few minutes before I came here.” The President went on to promise that if we couldn’t find a suitable place that was big enough for our prom, “we will postpone our dinner and I will come out on some other occasion.”

Even my dad, who always votes the straight Republican ticket, had to admit that Kennedy acted fast after that. As soon as the news conference was over, the President told his appointments secretary. Kenneth O’Donnell, to get busy on the phone to party officials in California.

And just a few hours later, press secretary Pierre Salinger announced that we would be able to use the grand ballroom after all, and that the Democrats would hold their fund-raising dinner upstairs at the same hotel, in the two smaller rooms—The Star On The Roof and the Escoffier.

“We hope the kids have a good time at their prom,” Salinger said.

Now that we’d been given back the ballroom, we reached for the stars. JFK had managed to have the hall returned to us; JFK was coming to California for the Democratic shindig maybe—just maybe—JFK would drop in on our prom.

Now just about everybody—Mr. Weybright and Mrs. Hill and most of the students—sent wires to the President thanking him for his kindness and inviting him to the prom.

Jim Tucker, our student body president, explained that the telegrams were aimed at showing Mr. Kennedy that no one blamed him for the mixup. “We wanted to let him know we’re not mad at him, but we’d sure like to have him come to the prom.”

Tom Giuffrida. in his official capacity as class president, spoke for us all when he said. “We’re very happy about it. Everyone’s really hoping he can come. He’s been known to do little things like this.”

Will he—won’t he?

Joan Bodley, our student body secretary, exulted, “We’re all looking forward to it. It would be a wonderful climax to our senior year. In fact, it’s become the main topic of discussion lately. We kinda feel he will come.”

The thing to do, we all thought, was to play it cool and act as if he were coming. So we told Al Hibler’s band to rehearse “Hail to the Chief.” And Mrs. Hill, using student body money, went out and bought a silver platter to be presented to the President, on which was the inscription, “To a Real American President.” If he didn’t show up. we could always send it along to the White House, we figured.

On the night of Friday, June 7, 1963, my date and I joined 540 other seniors of John Burroughs High School of Burbank in the grand ballroom of the Beverly Hilton Hotel in Los Angeles. Just before I left the house to go out to the car (which my dad had loaned me for the night), my father put down his paper and took a long, close look at me. And even though he knew that mom had already slipped me fifteen dollars, he opened his wallet and gave me an additional ten-spot. Then he made a strange snuffling noise in his throat that I’d never heard before and ducked down again behind his paper.

But at the prom I didn’t have time to try to figure out what had been bothering my pop. Too much was happening. There were Secret Service men and photographers all over the place, which seemed to indicate the President was going to show up any minute. So up, up went our hopes.

Then a rumor spread around the ballroom that Mr. Kennedy was so busy upstairs table-hopping among such celebrities as Jack Benny and his wife Mary Livingston, Marlon Brando, Gene Kelly and his wife, and Dean Martin and his wife, that he simply wouldn’t be able to make it to our prom.

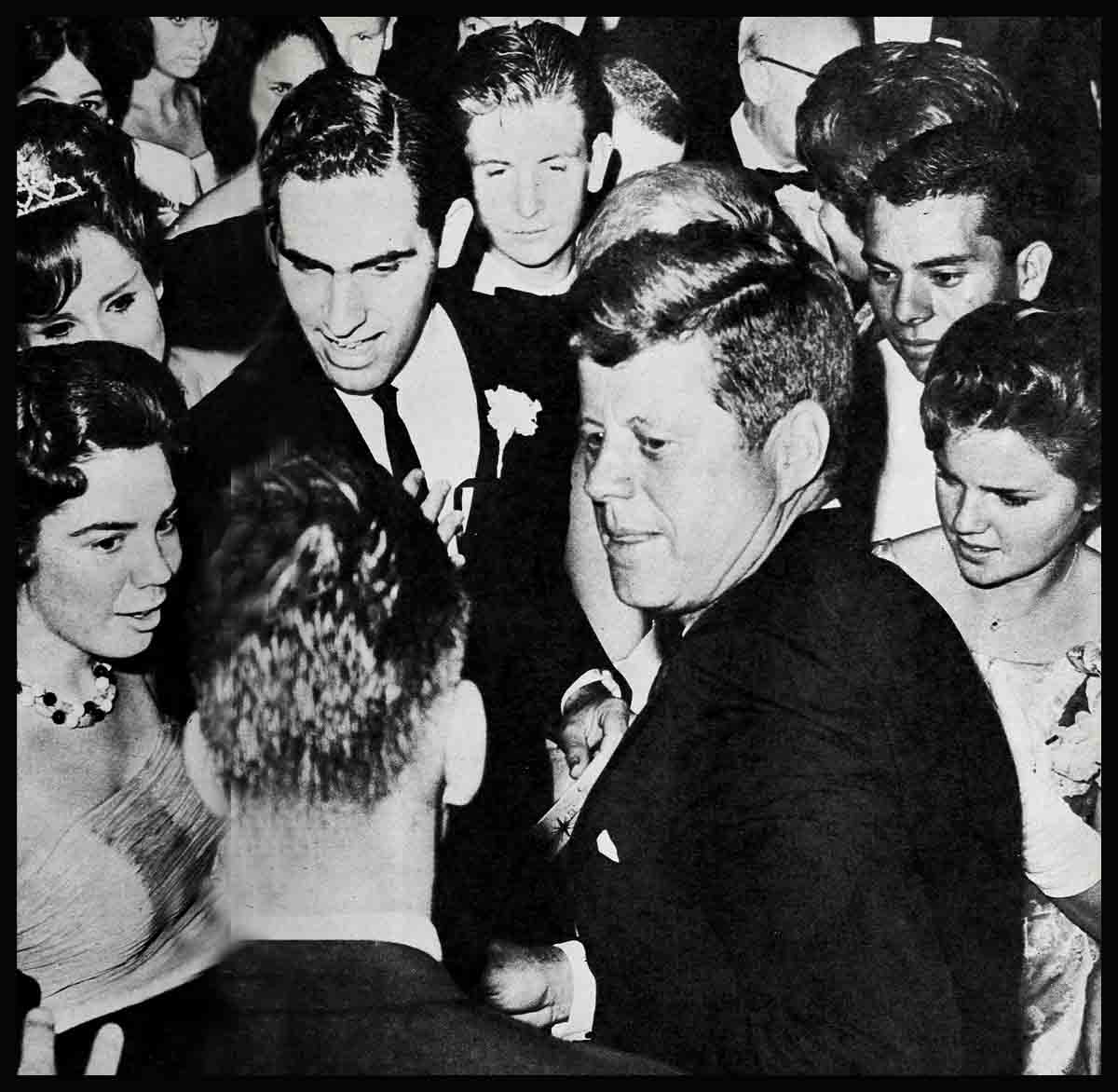

It was about ten o’clock, and we were all sitting around at the tables like two opposing cheering sections—one sure that he’d appear any second, and the other just as certain that he wouldn’t—when Al Hibler’s band struck up “Hail to the Chief.” There was a lot of yelling and screaming and flashbulbs popped off all over the place.

We all got up and pressed forward and there he was. The President of the United States. At our prom.

He had slipped in through a back door with Jack Benny. The two of them were making their way up to the bandstand.

How did I feel? Numb. I remember grabbing my date’s hand—or maybe she grabbed my hand—and the two of us were cheering like crazy.

What did I think about the President? Well, I was too excited to know.

Maybe it’ll help if I tell you what some of the other kids said at the time or afterwards.

Tom Giuffrida said, “As soon as Kennedy came in, it was great. First when I saw him I couldn’t believe it was him. I looked over and saw Jack Benny, too, and that was quite a surprise. The first thing I noticed about the President was what a tan he had. He looked so healthy. And he seemed—I believe I never thought of him as a human being before. I thought of him as something higher.”

Jim Tucker said. “He made things exciting! It’s a funny experience, because you more or less think of the President not as a person but as an office. And when you see him, it—it’s hard to describe. I thought he was really sharp. He looked fairly young. He looked a little different than he did on TV—more like he’d just been on the beach. The air about him seemed very informal.

“Everybody had been expecting him, but I didn’t notice the crowd reaction because I had my eyes on him. My girl friend [Barbara Duby] was excited—all of a sudden he’s there! It seemed like a dream. Of course, she was excited because I got to shake hands with him, since I was student body president.” Two presidents meet!

Joan Bodley said, “We thought he was cute. He’s a lot better looking in person than he is on TV or in the photos they take. He acted like the kids—he didn’t seem like the President.

“And he was really nice. There were so many people around him that I didn’t get to talk to him, but a lot of kids shook his hand. And I think he gave out a few autographs.”

Mind you, we didn’t push or shove or act up; although he acted like one of the kids, we never forgot he is the President.

He put us at our ease immediately when, standing up there on the bandstand with Tom, Jim. Rick and Mr. Benny, he cracked, “I want to thank you very much for letting us have the smaller rooms upstairs.”

Then he pointed to Jack Benny and said, “I brought my brother Teddy.” After we’d stopped laughing he added seriously, “Next to being President—in fact, rather than being President—I would prefer being a member of this graduating class tonight. And Mr. Benny and I are not too old. All this country is and hopes to be is in this room tonight.”

At this point my girl squeezed my hand real tight, and darned if my throat didn’t make the exact same sound that my dad’s had, for some reason, earlier that evening.

JFK and Jack Benny

But suddenly the President grinned and he turned to Mr. Benny and said, “Jack Benny will now give the address to the graduating class.”

By this time I was so dazed that I didn’t catch Benny’s exact words. But I remember he did tell us he was impressed by our affair because it cost only eighteen dollars-a-couple. He said he almost choked on the food upstairs when he found out it was costing $1000-a-couple.

While Mr. Benny was speaking, I noticed Rick Holbrook whispering to the President. A minute later. I realized what he must have been saying when he presented Mr. Kennedy with the surprise gift of the silver platter. The President seemed genuinely pleased as he smiled and said, “Thank you for the plaque.”

In six or seven minutes, it was all over. The Secret Service men closed ranks around the President, and he and Mr. Benny went back upstairs.

Maybe Jim Tucker summed up all our feelings when he said, “It’ll be something we won’t forget, that’s for sure. . . .”

Incidentally, my dad will be home in a few minutes, and I’ve got the answer for him to the stuff he spouted yesterday morning about those foreign high school students whom he claimed “attacked” the President. He’ll find the answer spelled out for him in his own newspaper; and just to make sure he sees it, I’ve marked the story in red pencil.

For the simple fact of the matter is that the students who “stole” the President’s tie clasp and handkerchief have returned them to Mr. Kennedy with explanations.

First, a Javanese girl phoned the White House and said she hadn’t known what she was doing when she grabbed the President’s white linen handkerchief, she was sorry and she was mailing it back to him.

Then, Bowo Soerjosoerdarmo, a nineteen-year-old exchange student at Harrison High School, Philadelphia, from Malanj. Indonesia, took a bus to the front door of the White House to return the clip with an apologetic letter explaining that he took it “in an exciting moment” when “I could not handle myself correctly.”

Wearing a green sport shirt and khaki pants, Bo (as he is known to his fellow students in the American Field Service student exchange program) sought out a patrolman on duty at the northwest gate and tried to leave the gold pin, set with tiny emerald-like stones, and the note of apology with it.

But instead, Bo was ushered into Pierre Salinger’s office, and in a few minutes he was escorted into the oval room and allowed to tell his story to Mr. Kennedy himself. “I hope that my action isn’t going to ruin diplomatic relations with Indonesia,” Bo said to his host.

A little later, Bo came out again with another tie-clip, this one a “doodle bug”—a gilt replica of the famed PT-109. Bo informed reporters, “He was smiling. I don’t think he was angry. He let me take his picture with my camera. Then Mr. Salinger took a picture of me and him. Mr. Kennedy said it was okay; I think he doesn’t mind.”

And if my dad still isn’t convinced that all high school kids aren’t headed for perdition, perhaps he will be by something else I just remembered about the night President Kennedy came to our senior prom.

It was quite a few weeks after the prom, actually, that a reporter caught up with Jim Tucker and asked him a few questions. The first was “Do you think this sort of thing could happen in another country—that a head of state would voluntarily give up a hall like Kennedy did?” Jim answered, “Oh, maybe in Britain. But I think that in a country where they have a dictator or something like that, where public opinion doesn’t matter, I don’t think something like this could have occurred.”

Then, when the reporter asked if Kennedy’s coming to the prom had made the government more real to him, Jim replied. “I think so. And I think it impressed upon the kids the fact that everyone does have a voice and it’s a good thing to organize so that you can accomplish something—even going as high as influencing the President.”

That should convince dad that high school kids aren’t all bad. For despite everything I’ve said, he is convincible. Cause even though he’s a rock-ribbed Republican, I want you to know that on the day after the prom he clipped Kennedy’s at-the-dance photos out of both his morning and his evening newspapers and, without saying a word, tacked them up on the back of the door to my room.

Sometimes I think there’s still hope for my father.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1963

No Comments