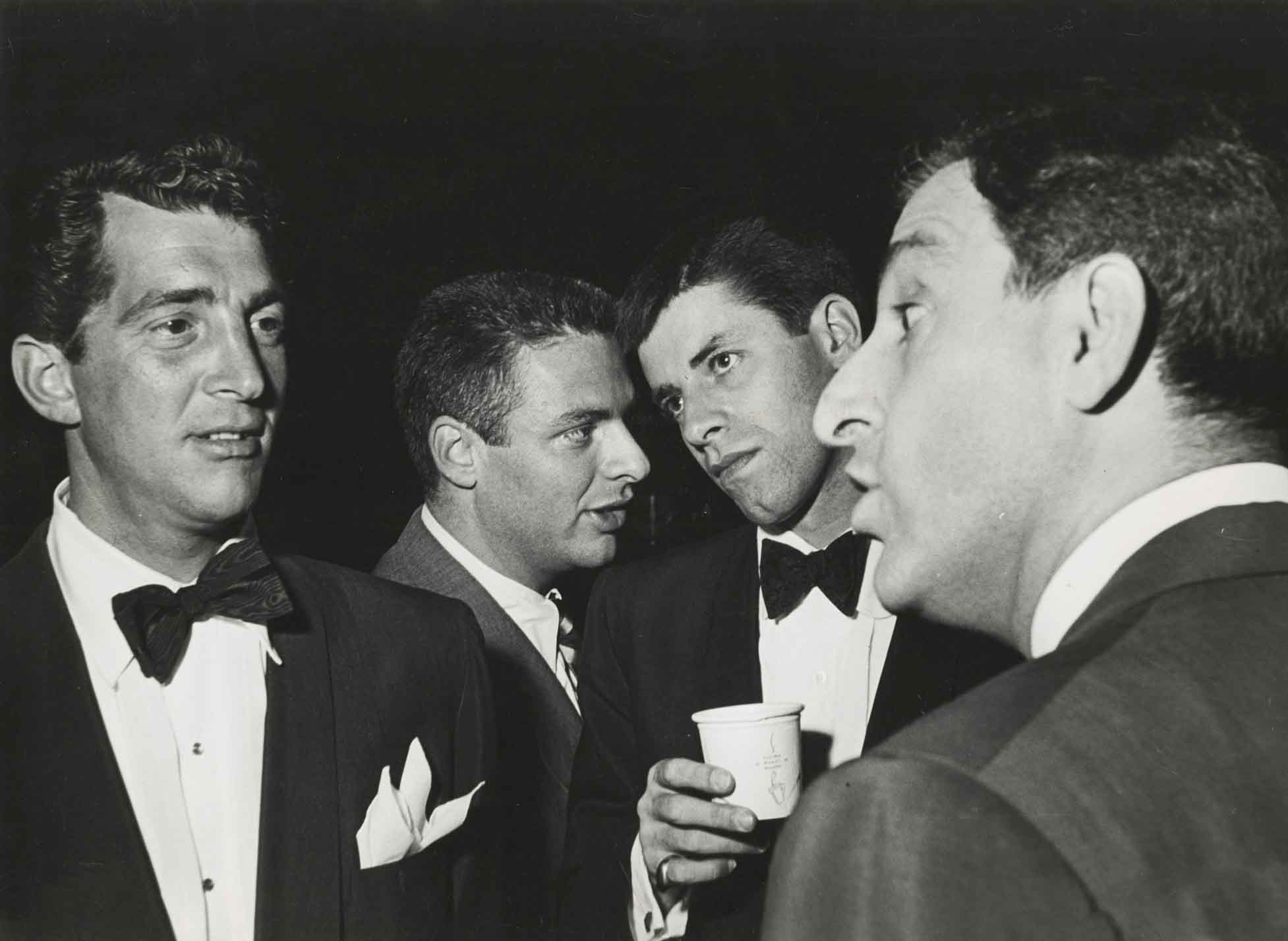

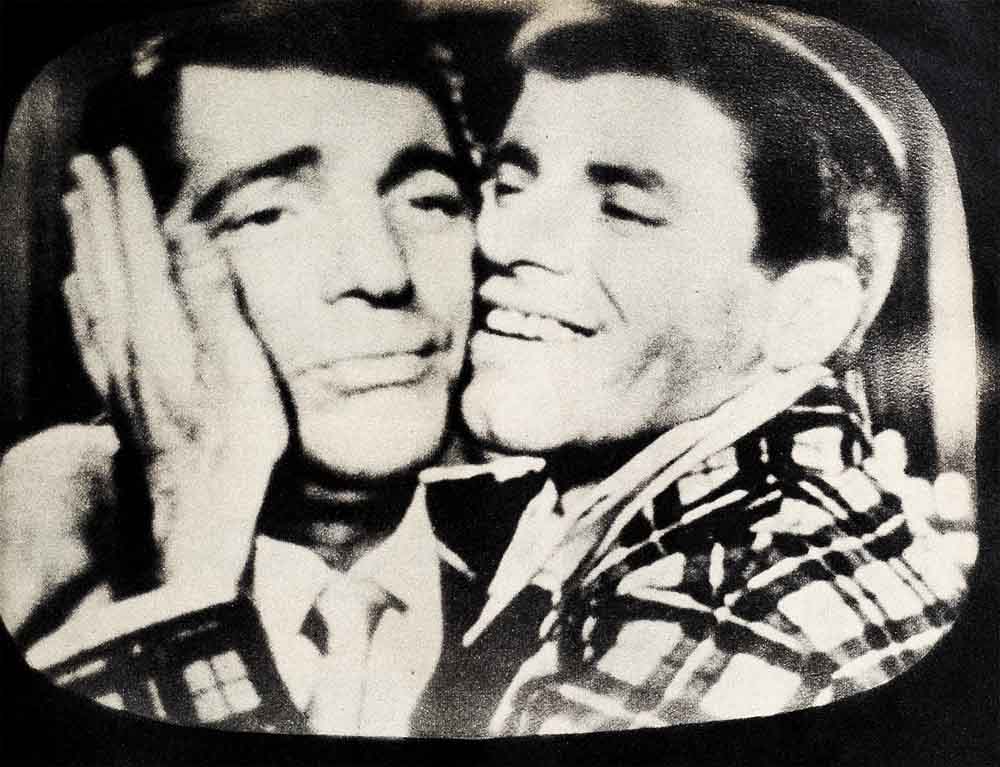

Are Martin And Lewis Breaking Up?

It happens to every team. One of them has a headache some day and gets annoyed at his partner for something that any other day he would brush aside with a cheerful grin. Immediately the rumors start to fly hot and heavy.

It happened recently to Martin and Lewis, as it must eventually happen to every team, but there’s no stopping this irrepressible pair. In the face of rumors that they’ve lost their magic formula and that theirs is becoming a partnership in name only, Dean and Jerry recently issued a statement acknowledging that they were in fact going to break up and go their separate ways—on July 25, 1996. This- will be some forty-two years from today!

For those close to Martin and Lewis, anytime within the next couple of hundred years would still be too soon. It would seem inconceivable that either Dean or Jerry could ever really split up. They’ve been bound too long together by a handshake that’s survived an eternity of experience. Their lives have been linked by too much—and too many.

Linked by a sea of happy faces which stretches limitlessly, by the sound of laughter —to them the most magical sound in the world —by the happy smiles of children like a little boy named Bill who sat in the front row of the El Capitan Theatre the other day watching their television rehearsal with feverish blue eyes, as though committing all of it to heart and memory. Beside him, a grave woman smiled when he smiled, laughed when he laughed and thanked Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis with all of a mother’s heart for playing the whole show straight to her boy—to those excited and feverish eyes which might never see them again, which might never see anything again. He faced an operation that might leave him blind. Anxious to give him something to remember, his parents had asked what he would like to see. “Martin and Lewis,” he said with no hesitation. And so this little boy became one more link binding Martin and Lewis together in a seemingly unbreakable chain.

Their lives are linked too by all those who may be affected by the $6,500,000 they’ve raised toward the eradication of Muscular Dystrophy and by their own knowledge that together some day they might well be the financial means of wiping this dread disease completely out.

The music Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis have made together is the happy music. The sweetest music this side of any place. The laughter to lighten the lives of millions of human beings the world over in tense times when they’ve needed it most. Laughter which must not stop.

More personally, Martin and Lewis will always be bound together by the million laughs they’ve had, the tough times and the triumphs they’ve shared since they met.

Theirs has been the most perfect wedding of talent in recent show business. Their magic formula, the heart behind their humor is an affinity almost too close to define. Together the handsome crooner and the comedian with the chrysanthemum haircut have proven themselves to millions of laughing, cheering admirers. As a team they’ve been indivisible and indestructible. And everyone who has tried to separate them has gotten a familiar answer, “There’s no Martin, no Lewis, only Martin and Lewis.”

Looking back on that day in 1942 when they were introduced on the street corner at 54th Street and Broadway in New York City, both of them feel that Fate must have had a lot to do with it. There doesn’t seem to be anything else that could have brought them together at that particular place and at that particular time.

But cymbals didn’t crash and the world didn’t stop. Nobody even gave them a second glance. At best they were an unlikely looking pair. An elastic-faced youth named Joseph Levitch, fresh from the Borsch Circuit, and an Italian barber’s son from Steubenville, Ohio, Dino Crocetti, singing protege of the boys in the back room of the local cigar store.

Although they didn’t get to work together as a team until four years later, Fate kept crossing their paths. Not long thereafter, a very nervous Italian crooner then billed as Dino Martini followed Frank Sinatra into the Club Riobamba in New York. Dino was so nervous he was sure the customers thought he was singing a rhumba and had castanets hidden in his knees. To make things worse it was celebrity night and the audience was almost entirely composed of celebrities. Wherever he looked, Dino saw famous faces. Unknown to him, however, a non-celebrity, Jerry Lewis, was sitting at the bar to escape the cover charge. He’d gone to see and hear Sinatra and didn’t know the bill had changed. But he didn’t ask for his money back. He watched, entranced by the sight of this unknown ‘who could sing to such an audience so easily.

That evening is indelibly engraved on Jerry’s mind, and he can still remember what Dino wore—a light blue dinner jacket that a waiter wears if people are coming and a maroon tie.

So much to remember. . . .

For Jerry—an indelible picture—the time he next saw Dino Martini, singing at Loew’s Theatre where Jerr was “an yoosher once.” Dino sang, clutching on to something in his hand. Curiously Jerry wondered what it could be. Later he found out—a little white cross.

For Dino—during the months after their street-corner meeting—Jerr’s casual correspondence on the walls of the dressing rooms in the club circuit where one usually followed the other. Jerr’s welcoming scribble, “Hi, Dino. I was here. Hope you do as well.”

For both of them—and for a laughhungry world—the memorable evening, July 25, 1946, at Atlantic City’s “500 Club” —when Martin & Lewis was born. Now married to Patti Palmer, Jimmy Dorsey’s pretty dark-eyed vocalist, and with hospital bills hounding them following the birth of a son, Gary, Jerry needed to make more money. When he and Dino were both booked into the “500 Club”—he talked the proprietor into letting them do their “big comedy act” together. The one that really laid them in the aisle wherever they played. But of course the first night they went out on the floor together nothing happened. Jerr did his mugging to records, Dean sang his songs and the rest slept. Except the proprietor. He blew his top. “You said you guys get laughs. I did not hear no laughs.” No laughs next show—and out they would both go.

They holed up that night in Jerry’s hotel room, locked the door and worked on colossal ideas they couldn’t use. Some time during the small hours—they went down to the beach, and using the breakers for a rhythm beat, Jerr taught Dean a time-step—the same one they do today. Sleepless and desperate, they arrived at the club the next night—still with no routine. Like condemned men with nothing to lose they descended upon the unsuspecting customers. A barrage of bedlam—squirting seltzer, snipping off the ends of customers’ cigars, chasing the waiters. Dean stepping on Jerry’s lines. Jerry stepping on Dean’s songs. And both of them walking all over the audience. To Jerr—from somewhere—there came a voice, a laugh-voice high and whiny that was to be imitated the world over. They wound up their act leading the hysterical customers around the club in a conga. That night two weary new comedians collapsed over a few beers—quite a few.

Like any couple—the first was their toughest year.

Too many unpaid bills following them around and catching them. In Atlantic City they stayed at a flea-bitten hotel. The management put an iron crib in Patti and Jerry’s room for one-year-old Gary. Patti laundered Gary’s diapers out daily and hung them on the fire escape to dry. Money was so scarce, Dean’s wife, Betty, had gone home to her mother’s in Philadelphia to have their third child, a daughter they named Gail. They couldn’t pay their hotel bills and finally left three trunks for security, walking out of the lobby with all they could wear and baby Gary. When they retrieved the trunks a year later, they found the moths had had a busier season than theirs. A wardrobe of moth-eaten rags.

These were days when Dean and Jerry would appear on celebrity night at Leon and Eddie’s for free dinner for four. When Patti had to go to the hospital and, wanting to surprise her by driving her home in their own car, Jerry bought an old beaten-up Plymouth for $600—and Patti was plenty surprised. “We don’t even have two dollars. What about the hospital bills?” The car was on its last gasp, but was Jerry’s pride and joy. Every night between shows at the Havana Madrid—how he would stand out in front of the club under the lights lovingly polishing it.

Unforgettable—ever—the night Martin & Lewis broke into the big time. The biggest. New York’s Copacabana. With all Broadway at their feet, and their price upped to $5000 a week. They’d come a long way then—in less than two years. But waiting in their dressing rooms two white-faced guys were ready to write off the whole thing. They’d paid a writer $1000 for Jerry’s three-minute opener. Watching Jerry over in one corner of the dressing room, struggling feverishly rehearsing the gags, almost before even he realized what

he was doing, Dean walked over, took the paper out of his hand and tossed it out the open window. Then horrified, they both stood there watching $1000 flutter slowly down to the street. For a minute they felt like fluttering down after it. Then with a confidence he couldn’t feel, Dean gave Jerr that famous third-quarter locker-room speech. “Now go out there, Jerr—and do what you want to do. Whatever you feel like doing,” he said. Jerr felt like folding up, period. Shakily making his way out on the Copa floor, he took a look around the packed club—and again from somewhere . . . or nowhere . . . the line came to him. “My father always said, ‘When you play the Copa, Son, you’ll be playing to the cream of show business.’” He paused and took another look around. Then in a cracked voice, “This is krim?” Hearing the laughs, the lyrics of “San Fernando Valley” returned to Dean’s mind. They’ve often wondered what would have happened if Jerry had done the $1000 material. “We probably wouldn’t be in Hollywood today,” they say. Jerry still doesn’t know where his sock opening line came from. But Fate was keeping a protective eye.

Exciting giddy days, these. The first flush of a fantastic success even Dean and Jerry couldn’t explain. Lines waiting six deep out in the snow when they played the Paramount. Breaking their own records wherever they went. Capturing the whole country with their uninhibited comedy, their absolute irreverence for anything—man or animal, vegetable or mineral. Beloved by audiences who sensed the heart behind their humor, their mutual affection and admiration, the way each extended himself to make the other look even better, the happy chemistry of two men who were meant to make laughter together.

Laughs. A million laughs. . . .

The hilarious times they’ve covered for each other. That night when Dean got back to the dressing room late, wondered where everybody was and rushed out on stage, wearing denims and sneakers, to find Jerry singing “Blue Skies” for him—and the audience in hysterics thinking it part of the act. Another night when Dean dashed back, slid into his pumps—and realized too late Jerry had nailed them to the floor. The night aboard a New York to Chicago train when Martin & Lewis went through a Pullman car around 3:00 a.m. knocking on doors and announcing, “We’ll be in La Salle Station in twenty minutes—La Salle Station—twenty minutes,” getting all the sleepy passengers out in the aisles, bags in hand—and Chicago still five hours away.

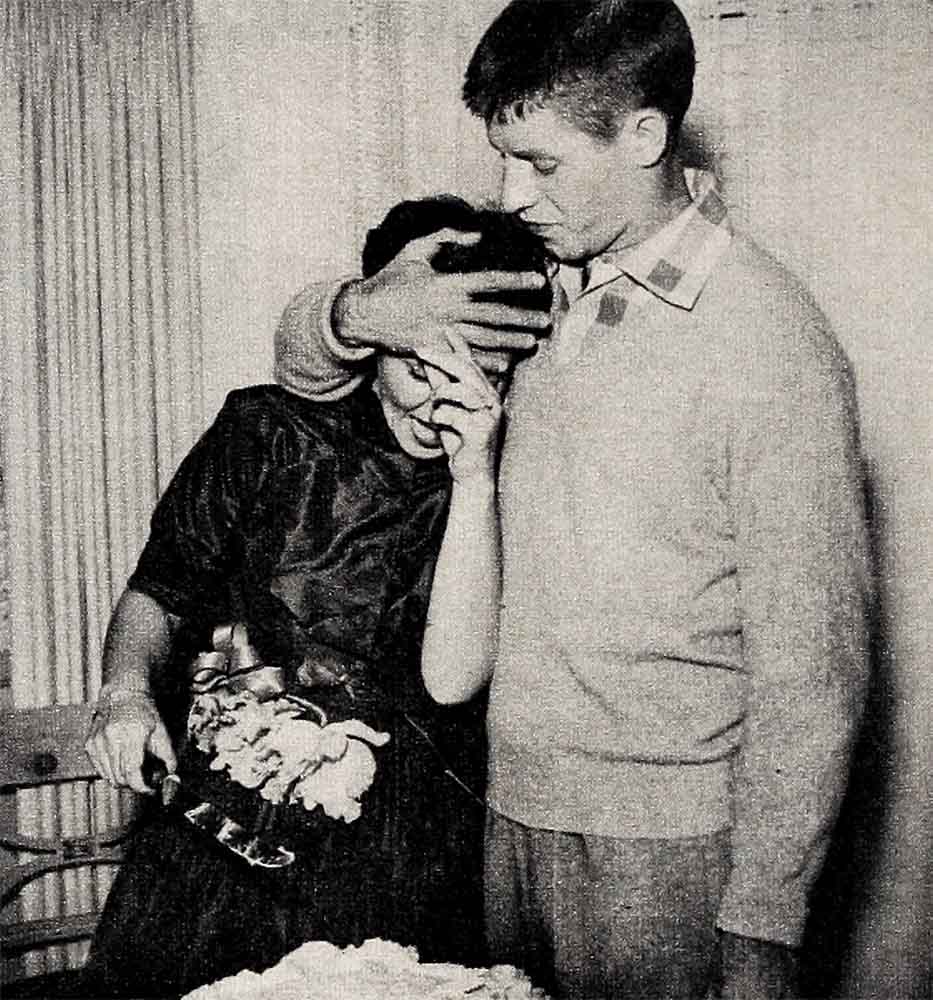

And how about that prank that threatened to break up the act . . . and instead backfired into becoming part of it? The afternoon Jerry was to revolutionize hair styles by making famous a chrysanthemum cut. They’d been playing three shows a night at the Chez Paree, and a tired Jerr went to sleep in the barber’s chair at the Ambassador-East. Dean suggested the barber really clip him for laughs. “I can’t do that,” he said. But Dean kept egging him on until he did, slipping him a $20 tip and saying, “Here—I dare you—” His long hair that he wore well-vaselined down was Jerry’s pride and joy, and he roared like Samson when he woke up and found it was gone. When he got back to the hotel room, Patti took one horrified look and said, “What have you done? Where’s your hair? My poor Daddy—” and burst into tears. The more Patti cried, the madder Jerry got at Dean. That night he didn’t speak to him when they went on the floor of the Chez Paree—until he heard the laughs of the crowd, just eyeing his porcupine cut. It changed the whole personality of the act—and today he prizes the scissors the barber sent him for a souvenir.

But there’ve been tears too. . . .

Tears through the laughs . . . like the command performance Dean and Jerry gave for a dying kid at midnight in a hospital in Jersey City—when they realized humbly how much the team of Martin & Lewis meant to others. They’d just finished their show at the Riviera and they rushed out the door into zero weather, praying they’d get there in time.

Tears too—when their show just couldn’t go on and each realized what “the guy who is half my life” meant to him. The night at the Copa when Jerry collapsed at the mike from nervous exhaustion and Dean wound up the act, singing with mist in his eyes. The time on stage in Minneapolis when Jerr fell in the middle of an acrobatic routine, they heard a tendon snap, and thought he’d broken his back. The theatre management carried him off stage, and facing an audience of five thou- sand, Dean started to sing, choked up, murmured, “Sorry—I—I can’t. . . .” and made a run for the ambulance to ride to the hospital with him. Another night at the Havana Madrid Dean had an appendicitis attack right in the middle of the show and Jerr couldn’t make with the jokes. For the next ten days, while Dean recuperated from an operation, he commuted between Lindy’s Restaurant and the hospital, carrying gallons of Dean’s favorite chicken soup with matzo balls. During a Chicago engagement, noting Jerry’s exhaustion one night, Dean had his Beverly Hills physician fly pronto to Chicago and order him home. All the threats for cancelled bookings met an unperturbed brown eye and Dean’s, “The kid can’t make it. Go ahead and sue. . . .”

And there were flops. Two. . . .

That night at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco when Jerry opened blithely with, “Good evening, Ladies and Gentle- men. I can’t tell you how happy we are to be in Frisco and—” and stopped, wondering why the whole room froze. While the veddy crowd in the Mayfair Room in Boston just didn’t dig them at all. Until finally, after a prolonged silence, Jerry asked, “Why are you mad at us? We didn’t write any books.”

Otherwise, bedlam at the boxoffice—everywhere. Two kindred comedians with the heart and humor of one, so kindred that once when somebody in the audience booed Dean for badgering Jerry, he stopped right in the middle of the act to explain, “This isn’t for real. Honest. I love him too. This is just part of the act. . . .”

Sentimentally to be remembered always—that star-studded opening at Slapsie Maxie’s when all movieland conceded there was finally something new under the Hollywood sun—the fresh zany humor of Martin & Lewis. They liked them. . . . liked them. . . . Dean’s daughter, Deana, was born that first year. The first to be born under more comfortable circumstances. That is, in an uncomfortable way. The team owed a quarter of a million in law suits at that time, and others pending.

Together—no gamble was ever too great to take. . . .

Unhappy with their first starring picture, “At War with the Army,” with nothing great in sight—and not sure just how far Martin & Lewis would go on film, Dean and Jerry bought up the rest of their contract with Screen Associates for $850,000, figuring, “If we make more pictures like this one, we’ll be out of business anyway,” still not realizing just how much Martin & Lewis meant to their public. Even that picture clocked $4,000,000.

The times—the so many times—one’s fought for the other, tongue and fist. . . .

Take that time in Philadelphia—when Dean’s fist connected with a wisecracker’s jaw and an amazed Jerry, who’d heard nothing, watched the guy slide the whole length of the saloon and wondered why his partner was that mad. And found out later it was because the guy had made a crack about Jerry’s religion.

Take England—and they don’t care if you do—where they almost started retakes on the Revolutionary War, each fighting for the other.

Take the time they’ve had convincing Hollywood there’s no Martin and no Lewis—just Martin and Lewis. When Dean wouldn’t sign with Capitol Records unless they agreed to sign Jerry too. “Are you crazy—what do we do with a comic?” Sign him or they would do—without—Dino Martin. They signed.

And how many times, only Dean and Jerry know, when Jerry’s battled the studio for a better break in the scripts for Dean. His part in the last one, “Three-Ring Circus,” Jerry argued, was for the birds. Finally they were faced with the decision of accepting the pee and showing up on location in Phoenix, Arizona, by midnight of the deadline given— or paying off a default clause in their contract that would cost them $1,500,000. Half the loss would be Jerry’s, but knowing how unhappy Dean was with the script, he said, “I’ll take my loss, Dean. Let’s not do it.” Expensive words. $750,000 worth of words. Dean wouldn’t let Jerry do it—and ow caught the plane and made the dead-line.

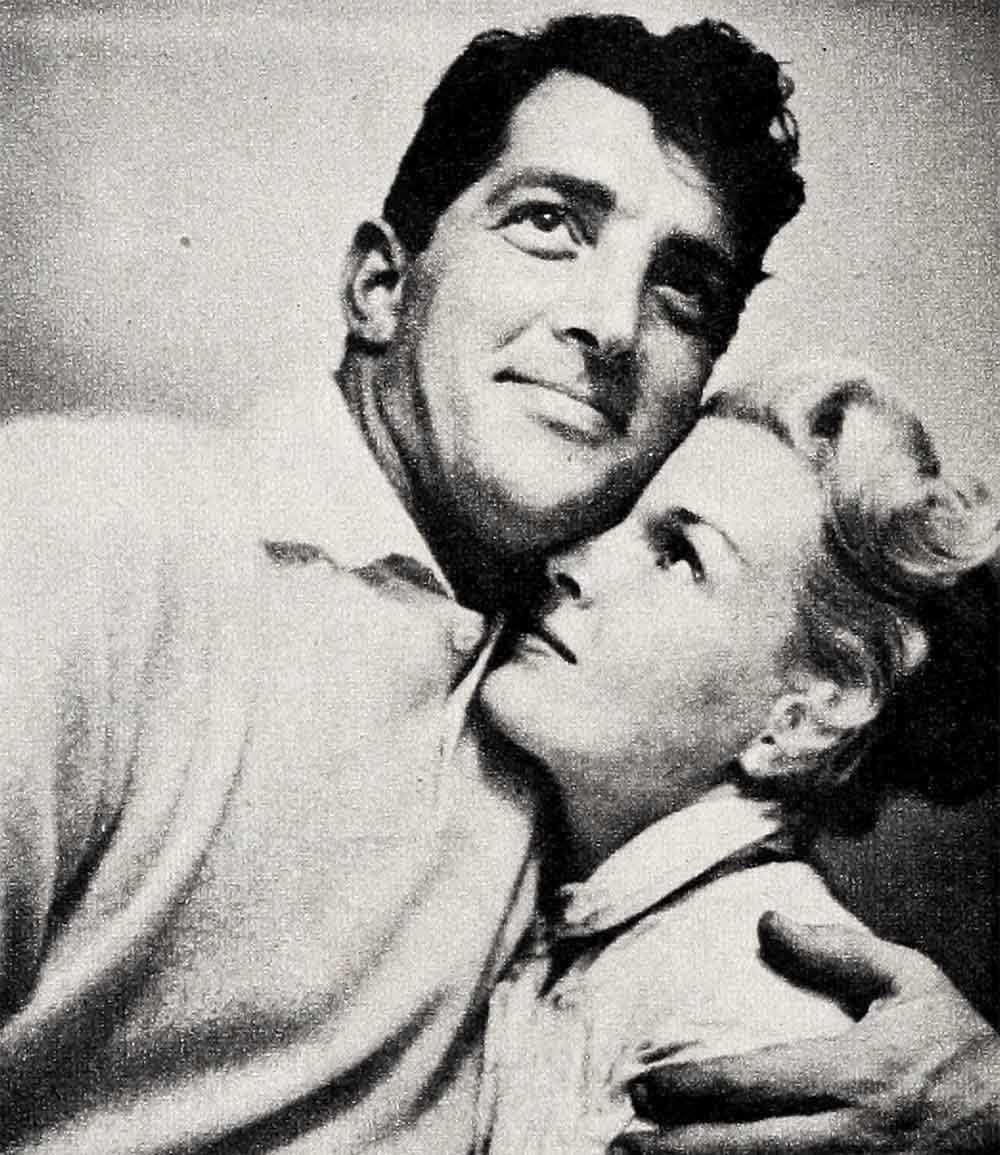

Share and share alike has always gone too where matters involve personal heartache and happiness.

Like Jerry being best man when Dean married pretty blond Jeanne Biegger, Florida’s Orange Bowl Queen. Getting so excited he jumped into the swimming pool with the bridegroom’s “going-away” suit on—and Dean joining him there attired in Jerry’s own best. And Jerry sharing his honeymoon night by arriving with Patti and Mack Grey at the Hotel Delmar ahead of the happy couple and then playing poker all night—the five of them.

And all those nostalgic times. . . .

Like Dean taking a sentimental journey around New Haven, Connecticut, with Jerry late one freezing cold night after their show—so Jerr could relive aloud the happy days when he and Patti had courted there. Standing with him out in front of the familiar old apartment next to the delicatessen store.

Sharing too the sad-hearted hours. . . .

When they were playing the Paramount Theatre in New York and the phone call came saying Jerry’s youngest son, Ronnie, had broken his leg. “If I could just talk to him, I’d feel better,” Jerr kept worrying. “If I could just hear his voice and know he’s all right.” The phone company in Hollywood ran a special line through the window of Ronnie’s room in the Children’s Hospital—so Jerry could say “Hello” before going on the next show. Even then he kept worrying—until Dean insisted, “Look, Jerr—take a plane after the last show. Go home and see Ronnie.” He would carry the show alone for one night, and if, with their 60 per cent arrangement, the management kicked, so what was money? “This is more important—go on home and see Ronnie.”

Each standing by. Always standing by—through the other’s family crises. . . .

Like Dean and Jeanne’s temporary estrangement after they’d been married three years. When a lonely, restless Dino, tired of baching, moved into the spare bedroom at Jerry’s house. And a tactful plotting Jerry and Patti kept constantly before him reminders of how wonderful having a home and a wife and a family is. Happy for him—when one day Dean slung his golf clubs over his shoulder, climbed into his Jaguar, and headed it towards his own home.

Of course there were other times. . . .

When any couple who spend as much of their lives together as do Jerry and Dean—could use some reconciling too. Like the morning they got off a train in Chicago and Jerry, in a depressed mood, sat like a cigar-store Indian, leaving Dean to make the jokes all by himself for newsreels and photographers.

And like the afternoon when Dean was late to television rehearsals . . . and Jerry finally blew his top and told him just how juvenile he thought it was—for a grown man to push and follow a little ball around a golf green. By way of apology, Dino sent him a handsome hand-made set of clubs with his name on them and a note saying, “I hope you use these—then you’ll understand.” And Jerr was so touched and contrite about the whole thing, to show his sportsmanship—he went straight out to the club. And the next day bought five pairs of golf shoes.

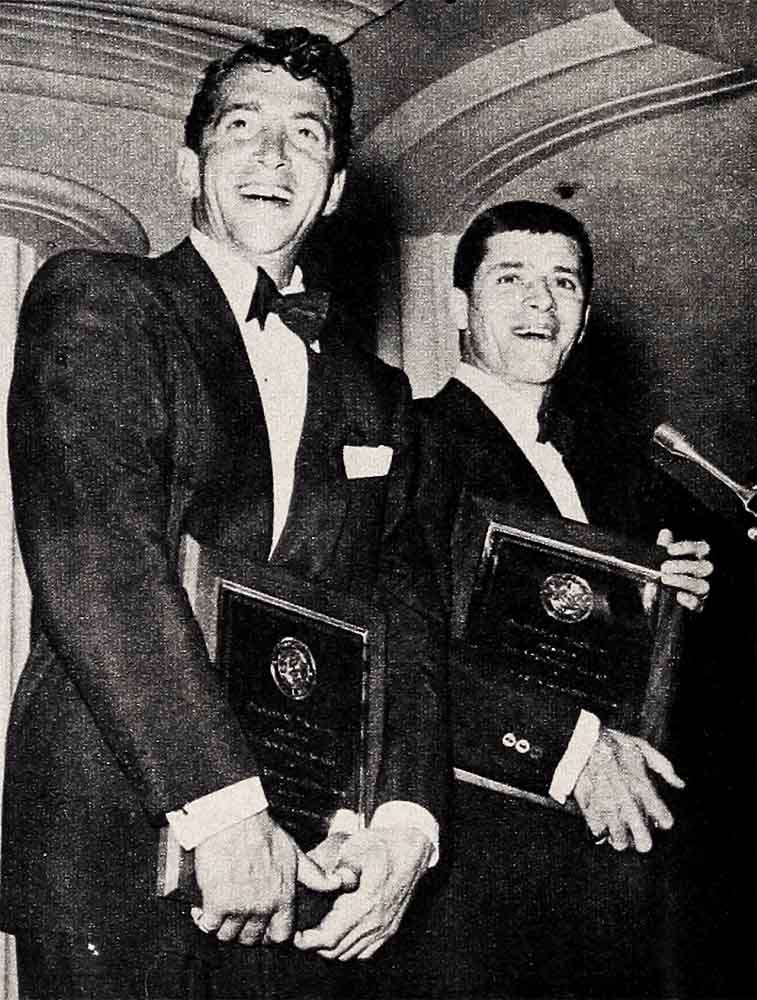

But most important of all to remember—the triumphs they’ve shared. When a victory for one has been automatically a victory for the other.

Such as when Steubenville, Ohio, celebrated “Dean Martin Day,” and tendered the golden key to the city to an Italian barber’s son named Dino Crocetti—who was more sensitive than any of them will ever know about some of them believing no good would ever come of him . . . and who’d vowed when he left ten years before—never to return until he’d proved differently. . . .

This is only one of too many days for two fellows named Crocetti and Levitch to remember just how far they’ve come together since that historic encounter on a strange street corner.

Only one of so many times shared—to be remembered.

“I don’t even want to think about it,” Jerry has said, when asked how he would feel if Martin & Lewis should ever separate. Dean sat there very silent, but his sentiment echoed Jerry’s when he added, “I’d be very happy for things to stay just as they are—for the next hundred years.”

To which the many millions for whom these two modern day medicine men make the happy music of laughter, add a prayerful “Amen.” Along with the reminder that the guy to whom each of them owes half of his life—is still Fate’s very good friend.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1954