The Hidden Panic Of Richard Chamberlain

PART I

One morning, back in 1954, sedate Pomona College in Claremont, California, suffered a shock. Hanging high on ivied Carnegie Hail, an outrageous painting startled students, faculty members and distinguished visitors crowding the campus for the annual Arts Festival. The lurid poster showed a twelve feet long and ten feet high sagehen, Pomona’s hallowed emblem, being bloodily crucified by a snarling lion. Beneath this blazed an accusing quote from Calvary: “They Know Not What They Do!” “They” obviously referred to the object of its scorn, Pomona’s prexy, Dr. Lyon.

Clearly, whatever sassy Joe College committed the crime, he was doomed to be bouncing right out of the school in disgrace. Yet nobody was—because to this day the crime has never been solved. That’s not surprising, but maybe it’s time to tell: The ringleader (a drama club buff sore at Dr, Lyon for disciplining a friend) was the least likely suspect in school. He was a model student and a perfect gentleman who was generally considered as menacing as a glass of milk. Today you know him as TV’s Dr. Kildare. He was known then as George Richard Chamberlain.

AUDIO BOOK

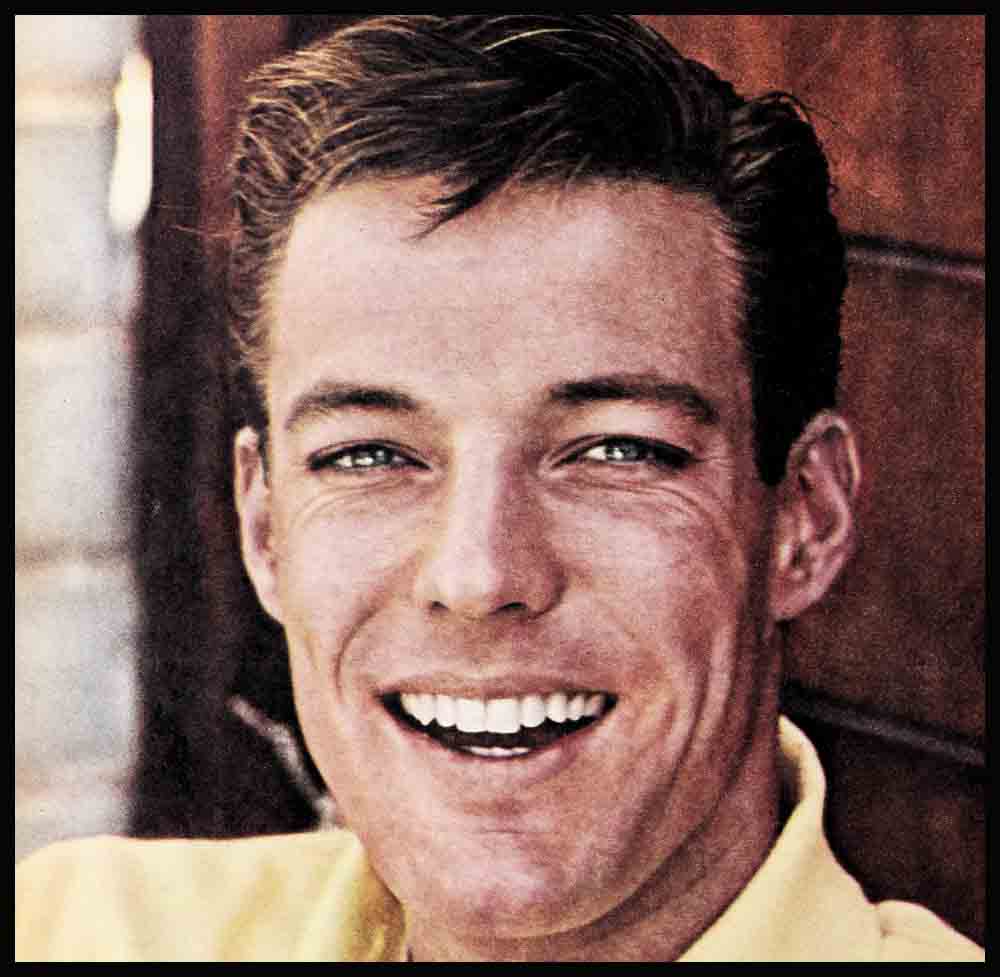

When that campus scandal broke, George Richard was only another Pomona sophomore chasing his Bachelor of Arts degree. But it still draws a bead on the blond, bland, 27-year-old TV charmer known today simply as Dick Chamberlain: outwardly, Dick wears the same mild mask of gentlemanly innocence that threw college authorities way off his trail. But lurking right beneath that mask is also the same iron nerve, disciplined determination, deadly sophistication and puckish flair that allowed him to pull off the bold prank. And lurking even beneath that lies the hidden panic of Dick Chamberlain . . . the fear that he’ll reveal too much of himself . . . the fear that people won’t like him if they know what he’s really like.

This contradictory combination makes him Hollywood’s most puzzling character, yet most formidable, hard-to-reach star.

Two years ago, when M-G-M picked Dick to play Dr. Kildare, a friend of his, Jack Nicholson, cracked, “It was inevitable. Who else could possibly look as antiseptic as Dick?” The remark is still good today; then it was perfect. At that point, the pleasant young nobody M-G-M tabbed for its big TV bid seemed as sterile as a role of gauze, and just about as exciting.

He was certainly handsome enough. Then, as now, his fine-lined aristocratic face suggested (as his drama coach, Jeff Corey, noted the minute he saw him) “a young Florentine noble—straight out of the Renaissance.” His mouth and nose were strong and straight, his hair a cap of pure gold. His slate blue eyes were large and set sensitively wide, “almost turning the corners of his face,” as his artist friend, Martin Green, points out, “so that you can see them from the side.” Overall, Dick had an inviting fresh, scrubbed and showered look, which later moved his comedienne friend, Carol Burnett, to call him, “squeaky clean,” swiping a shampoo ad slogan.

Dick’s body was quite strong and tidy, as it still is. It’s the body of a track athlete—star sprinter in high school and relays in college—whip muscled but spare. His fair skin gets a honey tan that gives him an Apollo like glow when he’s stripped down. That sight, seen as Dick worked out in bathing shorts, had once moved a co-ed named Claire Isaacson to gasp, “I’ve just seen a Greek god!”

Yet, with all this, Richard Chamberlain seemed hardly the type to set off romantic rockets around the world. He was so self effacing in person that you had to look twice to notice him. “Dick was all eyes and a mouth wide then,” recalls his pal and publicist, Chuck Painter. “He was the kind of a guy who comes into a room and fades right into the wall. Now that ‘Kildare’s’ a hit he is Coring out in all sorts of ways. But for many months he was quiet like a mouse.”

Dick was so quiet that when he was sent to Arizona for a bit in “A Thunder of Drums,” right after he’d made “Dr. Kildare’s” pilot at M-G-M, it was three days before the director knew who he was! On that same location, Painter persuaded a reporter from the Tucson Star to interview Dick. He soon wished he hadn’t. The reporter kidded Dick’s stiff reserve unmercifully, printing his cautious reactions word for word like, “I didn’t expect that question” and “I really don’t know what to say.” Dick has that first sorry interview framed today in his dressing room as a horrible reminder of how not to behave.

Even after “Dr. Kildare” began, its star was so unprepossessing that for weeks Dick couldn’t get past studio gate cops in his car without calling the publicity department for help. He had no decent dressing room because he couldn’t bring himself to speak up for one. After NBC had beamed him all over, Dick’s manner was so unimpressive that, when his car got stuck in heavy rain one night, he tried five households before one would allow him to call for help—and they passed him the phone outside on a long cord. Then “Dr. Kildare” leaped to TV’s top ten, never to drop out. And things have changed considerably since that day for Richard Chamberlain.

Last fall, as grand marshal of Baltimore’s “I Am An American Day” parade, Dick reviewed a crowd of 400,000 eager fans—then had to flee to a Coast Guard cutter in Chesapeake Bay to escape a mauling. In Pittsburgh, 450,000 swarmed the streets for a look at him in-person and the cops whisked Dick through back alleys to a safe stakeout. In New York he tripped a near riot when a kid spotted him despite levis and a sweat shirt before the lion cage at Bronx Zoo. In that same city Joan Crawford—a star Dick had gaped at as a kid himself—entertained him at her home and at the theater. “Because my girls are crazy about you—and so am I.” Corning back to Hollywood, Dick’s guest star was Gloria Swanson, queen of that town before Dick was born. Raved Gloria. “My most fascinating experience since “Sunset Boulevard.”

Right now, “Dr. Kildare” is out ahead of “Ben Casey” in popularity ratings and for 40.000,000 Chamberlain conquests (in the USA and 19 foreign lands) homework, of one kind or another, is tough to arrange when he’s on. Both his song platters are sellouts and Dick is skimping lunch hours to cut new albums. Meanwhile, at M-G-M, trucks dump more fan mail (13,000 letters a week) than ever swamped Robert Taylor or Clark Gable in their heydays. It’s from smitten females, mainly, of all ages. For instance Dinah Shore’s teenage daughter Melissa, who invaded Dick’s dressing room at his last TV spectacular, pretending to fix her hair. Or the middle-aged lady who snatched a chair be sat in—and gave the cops $8.50 to keep it. By now, maids and mamas from all over get the same wistfully rash ideas from Dick Chamberlain’s wholesome, clean cut spell. “I’m bringing my daughter out to Hollywood to meet you,” warned one frankly the other day. “You’re just the man I want her to » ” marry!

Surveying all this, Dick Chamberlain wags his handsome head incredulously. “I love every minute of it. sure,” he admits. “What guy in this business wouldn’t? Still,” he sighs, “it’s sort of unbelievable —isn’t it?” That it is—but Richard Chamberlain is even more so.

What Dick means, of course, is that barely two years ago he was just another obscure Hollywood hopeful, lost in the shuffle and spiritually down after fourteen boring GI months of exile in Korea. He was slugging away at lesson after lesson—drama, voice and ballet—but not sure he was getting anywhere and periodically telling his coach. Jeff Corey, “I’m going to quit trying to act.”

Living in a gloomy apartment house perched over a smog bound freeway and inhabited by decrepit old folks, he spent most nights hoping the phone would ring with a dinky job offer, which it almost never did. He was keeping body and soul together by chauffeuring a polio-stricken lady around.

Then suddenly, a year ago last September, Dick was blasted off to the stars in what his voice teacher and friend, Carolyn Trojanowski, rightly calls, “the most overwhelming thing that can hap- pen to a young man”—instant glory as the star of a hit TV series. That experience can indeed be devastating. It sent Gardner McKay, for example, emotionally shattered, off to the South American jungles to try and rediscover himself; it threatens to wreck George Maharis’ health and it has turned Dick’s rival, Vince Edwards, into a surly set tyrant with an apparent Napoleonic complex. By contrast, after fifty “Kildare’s” and almost two years of a pressured 7 A.M.-to-7 P.M. daily grind, Dick Chamberlain carries on apparently as smooth, fresh and cool as a mentholated cigarette ad. On TV he seems as pure as Sir Galahad. off TV as above reproach as the Queen of England. And Dick is not much help in cracking that illusion—and part illusion it is. “Hey,” cried a frustrated reporter. “Can’t somebody get this guy to say something stronger than that he’s against sin and loves his mother?”

“It’s just my phony front.” Dick himself grins. “I’m gradually growing out of it.” But that’s not necessarily so.

The truth is that all sides of Dick Chamberlain’s many faceted personality are as valid as government bonds. He is what he appears to be and what he doesn’t. And that is his hidden panic. “I know Dick seems too good to be true,” says one of his closest friends. Martin Green. “But it is true. He’s kind, clean, considerate and polite—as a gentleman. the greatest. Don’t forget, though, he’s an actor. In a sense, all of us are, because life is an acting game. Dick recognizes that. plays the game to the hilt and has a great time. He is not dewy-eyed, but realistic.” And if someone is hiding something, isn’t it better to bide it by playing the game?

Another pal, Bob Towne, an articulate young writer who like Green, chummed with Dick all through college. put it a little differently: “If Dick were religious—which he’s not—he’d be a humanist.” Towne believes. “He has great compassion. He couldn’t hurt anyone if he tried. Yet he’s a Stoic, too—in the classic sense—with an inner citadel of freedom. He’s superbly self-contained and his basic quality, I’d say, is toughness. inside, he’s the British officer type who could calmly dress for dinner in the jungle while the natives outside were howling. He’d be great to have around in a crisis. You see, what Dick has is grace and control under pressure.” Hemingway called that by another name—courage.

Carolyn Trojanowski hacks Bob Towne up. “Dick is a perfect example of a ‘cool head,’ ” she says. “He can look at himself and a problem objectively, analyze it and calmly set out to correct it at once. Eve never seen him blow up. He never will.”

Whatever his subsurface secret—courage, control, cool head or superb act—on State 11 at M-G-M. Dick Chamberlain is a white-coated paragon, the beau ideal of any TV producer. Compared to the turbulent tension of “Ben Casey,” “Dr. Kildare’s” set is a rest home, thanks mainly to Dick. He’s never late, never sick, never sore and always knows his lines. “Working with Dick,” his veteran colleague. Raymond Massey. says, is pure pleasure. He’s young but mature—a professional. Like a good golfer, he doesn’t press.” Female guest stars, from Suzanne Pleshette to Gloria Swanson trip over themselves beaming back Dick’s suave, courtly manners. David Victor, Kildare’s producer, recalls only one mild career balk on Dick’s part: Reasoning rightly that he ought to be a bit less boobily boyish after publicly interning almost two years, Dick quietly re-wrote part of one script and next day suggested pleasantly, “How about doing it this way?” Everyone was delighted and the new switch was painless.

Way out—of the Hollywood scene

After Dick recorded his first song, “Three Stars Will Shine Tonight,” the sound man, used to electronically piecing and patching other TV stars pretending to sing, yipped, “Glory—we’re in the free!” At that same first “take” Dave Rose’s whole orchestra stood up and clapped. Dick had worked the number out to perfection before he arrived. That’s the way he does everything.

But when Dick Chamberlain rolls away from the studio, in his gray Fiat 1200 convertible, he turns back the clock—and with him it’s almost as if all this had never happened. He steps far out of the after-hours Hollywood scene, in which he has no place at all. Instead of operating like a top young bachelor star who has it made, Dick acts as if he were nobody still struggling to score.

After a quick meal, usually at Hamburger Hamlet or Norm’s Drive-In, Dick Chamberlain goes home to a remote pad that would thrill Pete the Hermit. Perched in the hills back of the Hollywood Bowl, it’s seventy-five yards back from a winding mountain Street and so masked by tangled growth of all kinds that you’d never find it without a helicopter. Up a plank ramp there’s just one big wood panelled room, a tiny kitchen, bath and a sun deck. A piano sits against one wall (Dick’s an accomplished pianist) and a small desk, chronically cluttered with bills and assorted mail, by another. There’s a chair, and only recently did he replace a beat-up chaise which departed cats had hopelessly soiled. A ball with a candle inside, that Dick dug out of a junk heap at M-G-M hangs from the ceiling, through which, not long ago, a family of raccoons surprisingly dropped. A tape recorder, TV and stereo sit here and there and, of course, there’s a bed. Also, behind a convenient closet door there is always a pile of shirts and shorts which Dick takes to a laundry now and then but, if stuck, washes himself. Not long ago, Martin Green looked up from a book he was reading to see Dick bustling out with a soggy armful which he proceeded to string on a line. “And now,” announced Chamberlain with mock gravity, “the famous Hollywood star will hang up his wash!”

Dick rented this hideout shortly before M-G-M signed him and, despite all that’s come his way since, has never seen fit to leave. He paid $75 a month at first, because he took on the gardening. Too busy for that now, he pays the full $100. He’s making a hundred times now what he did then, which was close to nothing. He stays not because he’s a miser but because the splendid isolation suits him. When he stretches out in bed with the next day’s shooting script, deer nibble his shrubs outside, coyotes pierce the night with howls and squirrels scamper among the potted plants he carefully tends on his deck and swipe the goodies he spreads out.

When Dick is home he’s almost always by himself. “I never entertain,” he admits. “I doubt if twenty people have been in my place since I’ve had it.” On his coffee table a candy jar, filled two years ago to offer guests, is still full, and the sweets petrified by now. Visitors are so rare that if one raps on the door there’s invariably a “wait a minute” and a scurrying sound inside as Dick hastily tidies up the place. Such privileged callers are not newfound friends of the Hollywood glamour set. Dick has none. Social gates are wide open to him by now, but he doesn’t even look.

“You approach Dick Chamberlain so far,” complained a frustrated hostess recently, “and then he goes behind a wall.” His lone publicity date on record was with Rossana Schiaffino way back at the premiere of “West Side Story”—and, with due respect to Rossana, that was because Dick wanted to see the picture, didn’t have a date and couldn’t go alone. But when photographers tried to bunch him with “the Hollywood young set,” he politely refused. “I’m not anti-social,” explains Dick. “But I am busy.”

That’s very true talk. Dick Chamberlain couldn’t be much busier without being twins. Despite a 5:30 alarm, Dick moonlights two nights of his five-day, all-day week on “Dr. Kildare” with lessons—dancing at Renova and Renoff’s and voice training with Carolyn Trojanowski. He’s also president and prime mover of Musical Presentations Theatre, a non-profit operetta workshop which Carolyn set up to give her pupils audience experience. Recently MPT staged its annual full dress show, “Potpourri” in the Pilgrimage Theatre, right down the mountain from Dick. It took weeks of late rehearsals. Dick sang “The Rape Song” from “The Fantasticks” and as El Guyo whirled around in a wild dance, and was boffo boy of the show.

“Dick is as hard working and conscientious a pupil as I have,” States Carolyn Trojanowski. “He never lets a day pass without thoroughly warming up his voice. It’s a good light bass,” she classifies, “but it lacks power. Dick will never sing opera but he can develop a very good stage-musical voice. That’s what he’s determined to do, and he will—wait and see.”

To develop the power, Dick methodically jogs along mountain paths near his place, at dawn or dusk, works out with weights, huffs through sets of breathing exercises and makes canyons ring practicing scales. Diet is never off his mind; when he heard Joan Sutherland sing out robustly at a recent performance of the San Francisco opera he cried, “My God—what do you suppose that woman eats?” He faithfully supplements his own meals with high-protein snacks prescribed by Miss Trojanowski. One, that was especially recommended, was raw liver whipped up in a blender. Dick tossed in red wine to kill the nauseating taste, still gagged. but kept downing it. Then one day he read where raw liver was loaded with uric acid and led straight to galloping gout. Only then did Dick happily switch to strawberry yoghurt.

Martin Green nods at this. “Dick would. He has to have a reason and a method for everything. Do you know how he stopped smoking? It was beautifully planned. He was on straight cigarettes, so he switched to filters. After a few days he added filtered holders to the filters. Next he dropped down to de-nicotinized sticks, something like smoking warm air. After that, quitting was easy.”

Green, a hard working serious painter, is typical of the few friends who feel free to rap on Dick’s door. Most are like Dick himself—smart, talented, up and at ’em, ambitious doers. Most, too, are former Pomona rah-rahs. Besides Martin, there’s writer Bob Towne, David Edwards, a novelist, Dave Ossman, a San Francisco radio man, and Hal Halverstadt, an editor now in New York. To that list you have to add Clara Ray, Dick’s steady girl friend.

Clara is a pretty, brown eyed, button nosed Memphis, Tennessee, you-all, raised in Eagle Rock, California, and trained as a lyric coloratura soprano. Unlike Dick she’s an extrovert—a former pom-pom cheer leader—and as full of beans as a Boston belle. “Dick shy—stuffy?” exclaims Clara in wide eyed wonder at the thought. “Why he’s anything but! It just takes time to know him.”

It took Clara a whole year. She first spied Dick two years ago at Carolyn Trojanowski’s studio. “We were rehearsing for a Christmas show,” Clara recalls, “the first time everybody was there at the same time. Dick was in the bass section—way in back, and he never moved out. But when we ran through ‘More I Cannot Wish You,’ it was so lovely. He was more than good looking—he had a quality that made you remember him.”

For a year. though, the only communication Clara had with Dick was a “Hi!,” flying in and out of lessons. For a long time she didn’t even know his name. Then MPT got going with Dick as prexy and Clara secretary. After the first “Poppourri” there was a cast party. Dick and Martin Green drove Clara to the blowout. She was also singing at the Statler then. “Why don’t you come down?” suggested Clara with true Southern hospitality. Dick said fine; he’d pick up a date for Martin.

“He came down, all right,” smiles Clara. “But not with Martin.” After that— “Well,” she sighs, remembering, “what can you do when you break out in a rash?”

Now Dick and Clara make a steady team, three or four evenings a week. But usually their fun’s synchronized with some career project. Because what means most to Dick Chamberlain—his work—is seldom far from his thoughts.

The other night staring at a movie scene, Dick suddenly muttered, “Oh—yes.”

“ ‘Oh yes’—what?” inquired Clara.

“Nothing—just a bit of technique, that’s all.”

But he had her nibbling. “What technique?” pressed Miss Ray.

“I can’t explain,” Chamberlain dismissed it. “It’s just something you learn in class.”

“And that,” says Clara, “is what you’d call subtle persuasion. You see, both Dick and Carolyn have been bugging me for months to take dramatic lessons. I’m a singer, so to me that seems a waste of money. But I know I haven’t a chance. I’ll be taking them if I stick around Dick.” Not long ago Clara played a small part in a “Dr. Kildare.” Actually, she was so good that cast and crew plugged to have her join the show as a regular. But when Clara saw the rushes with Dick she hid her face in her hands. “I had no idea I did all those God-awful things!” she wailed.

“You really did, didn’t you,” he re- plied, rather ungallantly. “You have to be shown, don’t you?”

Dick Chamberlain’s stern dedication to self improvement and his cool, correct manner of tackling it are his trademark with all who know him. “Dick,” his friend Bob Towne, told him the other day, “you know, your greatest virtue is also your most besetting sin—you’re always a perfect gentleman and scholar!”

“Oh, Lord,” Dick came back. “Not that again!” But it’s true. And it’s very hard to beat, everyone agrees. “Dick is quietly but steadily going about improving his acting instrument,” observes Towne seriously. “I think his scope is unlimited.”

Bob Weitman, head of M-G-M, puts it another way: “Richard Chamberlain,” he’s said more than once, “is the most promising long-range star we have here.”

All this work and no play, of course, could conceivably make Dick a dull boy. To more than a few that’s just what he seems to be. However, Dick Chamberlain can—and usually does—break out a far more colorful side when he’s within his tight little circle of old friends. Among those, in fact, he’s known as a party clown and show off who, as one says, “will climb up a wall if he has to, to entertain.” Dick has even wriggled through limbo exhibitions and twist frenzies at Carolyn Trojanowski’s, after “Potpourri” shows. Usually, though his fun stunts are sophisticated, Creative and, in effect, performances. “Noel Cowardish,” is the way Bob Towne describes them.

If there’s a piano handy, Dick will sit down and start rippling the keys with Debussy or Ravel, correctly and with feeling. But before anyone knows it, he’s off in wild improvisations which are pure Chamberlain—and killing burlesque. Not long ago at a “Potpourri” cast party at Martin Green’s Costa Mesa studio, things like this went on till dawn, helped along by champagne in paper cups. “Dick did a fake strip-tease with all the props that was paralyzing,” Green recalls. “Then we all sat around my electric organ and took turns composing and singing operas. Dick loves to take something like that and go with it. He always has.

“I remember,” Green goes on, “one winter back in college, we—Dick, Dave Ossman and I—semi-stole Dick’s mother’s Lincoln and took off for San Francisco. What I mean is, we were nice enough to leave her a note. Anyway, the trip was a glorious debacle. We practically froze because the power windows stuck wide open, we ran out of gas and money, almost starved—about everything happened to us except landing in jail. Back home the gang got together for a party and Dick headed for the piano. He sang a long, witty piece he’d composed that included every private joke and hotfoot of that trip. He had us rolling on the floor.”

“Dick has a devastating wit,” confirms Carolyn Trojanowski. “No one he knows well is safe, especially himself. It’s always Creative and you never know when he’ll let it fly.” A while back Carolyn was giving Dick a hard time in a tough voice lesson. As she left the room to answer the telephone she noticed Dick draw a straight line on the blackboard. “When I got back,” says Miss Trojanowski, “it was covered with a web of other straight lines. They formed a kookie sort of abstract portrait of someone you didn’t particularly like too much—undoubtedly me!”

“I don’t know him”

But even Dick Chamberlain’s closest friends recognize a line behind which Dick occasionally steps to become someone nobody really knows, possibly including himself. Carolyn Trojanowski, who has known him before he went to Korea, says, “Sometimes I have no idea what Dick is thinking. I might think I do. but I can’t be sure.” Clara Ray, thoughtfully fingering the diamond pendant Dick gave her admits, “The longer I know Dick the more I realize I don’t know him.” And Martin Green, who has painted two portraits of his pal. muses, “When Dick sits for a painting his personality seems to turn inward. He’s not easy.”

Like all true artists, Green paints what he sees—inside his subject related to inside himself. What came out on canvas the last time was a fascinating but disturbing study mostly in black, deep brown and yellow. The eyes are somberly glowing, the lips rebelliously set. The mood is brooding, intense and a hint unhappy. To Dick (no mean painter himself) it had, “a forward motion and restraint at the same time—expressing a sort of inhibition.”

Dick has bought many of Martin’s pictures to hang on his walls. He took this one home. The other day he brought it back. “I’m afraid I can’t live with it,” he told Martin.

Dick Chamberlain’s critique of his portrait, by his best friend’s brush, is a neat and honest self-analysis. He has had other analyses, too, professional ones, inviting the real Dick Chamberlain to please step forward. That is a maneuver popular with today’s young actors, to improve their art. In Dick’s case it is partly that but more: There is evidence that, despite everything that has come his way Dick Chamberlain is far from satisfied with himself as a person. He would like to know himself better, crack his mask of reserve and let more of his new world in. But with him that’s a tough order.

The other night a friend dropped by Dick’s hideout on his way home from the beach. “Dick offered me a brandy and we had one, then a few more,” he reports. “He began to open up. I don’t remember all that he said but I got the impression that down deep Dick feels a bit unfulfilled and lonely. He mentioned what few close friends he really had and how hard it was for him to make new ones.”

If that’s true, the feeling is nothing new with Richard Chamberlain. Most of his life he has been in some spotlight or other—but essentially alone in a crowd. all that time he’d had everything anyone could wish to make him confident, easy and open—good looks, health, talent, brains—plus the ability to go after what be wanted and get it. Whether it was grades, girls, sports, art, acting or honors Dick could wind up a winner. He had security too; a good home and well-off enough parents. The worst sickness be ever had was measles, his only accident a broken toe. “To this day,” says one old friend, “Dick hasn’t had a really hard knock. He’s never needed one.” Yet, somehow a sign, “Private—No Trespassing,” has hung on him almost from the day he was born right in Beverly Hills, at 6:30 P.M., March 31, 1935. “Only five and a half hours away from being an April Fool,” Dick points out. “I’ve always thought the margin was too slim.”

He’s kidding, of course. Neither brains, nor much of anything else was lacking in George Richard Chamberlain’s heritage. It was solid and solidly American, including a touch of Indian blood on his father’s side, which you can spot in Dick’s high cheekbones and, perhaps, in his stoic reserve. The rest, as Dick breaks it down, is “two-thirds English and one- fourth German,” and he owns the sturdy yet sensitive traits of those races, too.

His dad, Charles Chamberlain, came from Indiana, went through Indiana University, played football and injured a leg so badly that a Hoosier doctor told him it would never heal. So, Charles came to California “to die” in the sun. Instead he got well, found a job in a service station.

One day a girl with the marathon name of Elsa Winifred Von Fischer Benson drove in for some gasoline. Elsa was from San Francisco, where her grandfather, a refugee from Germany, had come in a covered wagon. She was blonde, pretty and musical. Her own mother had been on the stage and Elsa had sung briefly herself. However, any ideas she may have had of a career vanished when she fell in love with the husky, handsome gas station attendant. As soon as Charles Chamberlain found a better job as salesman for City Refrigerator Company, they were married. By the time Dick came along his brother, William, was almost seven. After Dick, Elsa had another son, but he died at birth. That left Dick not an only child but still a lonely one.

Because, more than an age gap separated little “Dickie” Chamberlain from his big brother. “I was never very close to Bill,” Dick says. “He was all the things I wasn’t—outgoing, sporty, handsome, romantically confident with girls, and, of course, way out ahead of me.” “Billy” was a true chip off his aggressive, man’s man father, and he followed in his footsteps. He went back to Indiana University, took Business Administration, married early and today those Chamberlains work together, manufacturing fixtures for Stores and markets.

Throughout Dick’s boyhood, though, Bill’s glamorous trail cast a backward shadow in which Dick Chamberlain felt chronically blotted out. Dick appraises himself then as, “a shy, serious, lugubrious kid, painfully thin, with a long sad face.” Back of it, however, lay an adventurous spirit which, even as a tot, made Dickie both a personage and a problem on South Elm drive.

The Chamberlains lived on that pleasant, middle-income Beverly Hills Street from the time Dick was two until he left for college. It’s a Street where apartments mingle with modest houses. Dick’s home was one of the nicest—a comfortable seven room Spanish type stucco with a Mexican tiled patio in back and out front two huge pittasporum trees shading the lawn. But for some time this haven was a prison for Dickie and he contrived to spring himself at every opportunity. Elsa Chamberlain, going about her housework, would spot Dickie contentedly playing with his toys or pet turtle one minute. The next time she peeked he was gone. A crack at the door was enough; he’d scoot out like a tiny scatback.

Usually, she found him wistfully hugging the fence surrounding the playground of Beverly Vista school down the block. But sometimes he ventured further and then the police would have to be called to round him up. Excitement was rare on respectable South Elm Drive; the only real rumble was once when a reputed “gangster” got himself shot in a nearby apartment. So, neighbors threw open their windows, leaned out hopefully then slammed them shut as bluecoats led Dickie dismally home. “Just that Chamberlain kid running away again,” they muttered.

What got Dickie in dutch was pure loneliness. His downfall was the siren sound of kids shouting at play out on the Street. The biggest, most inviting cacophony came from Beverly Vista school.

Dick went there when he was six. By then Billy was on to greater glory at Beverly Hills High, but his golden aura still lingered. Dick didn’t dare hope to match it; he just wanted friendships and fun. His mother took him the first day and they watched a new little girl stage a crying scene when her mother left. “Now,” said Mrs. Chamberlain. “isn’t that silly?” Dick thought so, too. He was proud that he didn’t cry. But why should he when he was finally where he’d longed to be? In a few day s he wasn’t so sure about that.

It came as a rude shock, Dick remembers, that school was not just one long, happy romp on a playground. He was also supposed to learn things—laborious and rather uninteresting things at that. This wasn’t what it was cracked up to be. Again he found himself a celebrity, in reverse. “For a while I refused to let them teach me anything,” he recalls. “I earned a unique honor—the most uncooperative kid in school.” No threats, or appeals to his parents did any good. It didn’t even faze Dick when they put him back a half grade. Worst of all was learning to read. He didn’t really get with that until he encountered a patient, under- standing teacher named Florence Montgomery in Fourth Grade. She took time after class to break down his rebellious block, and for that Dick is still grateful. “She was a wonderful woman,” he says, “and I really don’t know what would have happened to me without her.” Yet, even today Dick Chamberlain has trouble with oral reading. It handicapped him when he was trying out for his first Hollywood jobs. Learning lines is no problem but give him a script to read—as Dick often faces for charity appeals, promotional stunts and such—and he gums it right up.

Back then, Dickie Chamberlain gummed up about every conforming situation he ran into. He finally got through Beverly Vista with a passable C-average, but he hated school, organized sports, teams and regimented games. He was the fastest kid in school; he’d run a race with anyone—and he usually won. But when he couldn’t he’d quit.

“One time,” Dick recalls, “I ran the 100 in a YMCA track meet against kids from all over town. I took it for granted that I’d win—I always had. But suddenly several guys were out ahead of me and pulling away. So I stopped running. Everyone was sore. They said, ‘It’s a race, and you finish a race, win or lose!’ That didn’t make sense to me. I like to think that quitting that race was the last honest thing I ever did!”

Dick was always joining this and that group under pressure, then unhappily toughing it out. Cub Scouts bored him silly and he never did finish weaving his Indian basket. BSA experience was as unfruitful. “Troop 37” somehow elevated him to First Class Scout before he defected but his record is undistinguished. The summer camps at Buckhorn Flats in the mountains and on Catalina Island were okay, mainly because they were outdoors. But he never earned a merit badge. “I did win a soapstone carving contest,” allows Dick. “I carved an arrowhead with my initials on it.”

Sundays Dick had his arm twisted and trotted dutifully off to the Beverly Vista Community church. He even stood in the choir briefly, singing, “Holy, Holy, Holy” as an alto with a bunch of lady sopranos. “I hated it,” he admits honestly. “But I had to go. I’ve always hated anything where I don’t have freedom of choice.”

Given that, Dickie Chamberlain was as normal as the next boy. On his block, which “throbbed with kids,” he freewheeled happily around with junior citizens on the loose named Skeeter, Kurt, Mary Anne, and another Dickie, last name Vennaman, who lived right across the back alley. They worshipped the same girl, a baby doll named Arden, and beat up each other regularly. Dick looked like a mild tow-headed cherub but, as always, his looks were deceptive. With the gang he heaved dirt clods at passing cars until one target turned out to be a cop patrol, and that was disaster. Periodically, a circle of kids gathered under Dick’s pittasporum trees to watch Dick and Kurt, with whom he had “a personality conflict,” slug it out. Dick nursed his wounds with a horned toad which he kept in his room. “An ugly, exotic beast,” he remembers, “that seemed beautiful to me.” When it died he still kept it, hidden in a drawer until the smell gave him away. Another precious possession was a disreputable alley cat named “Tommy.”

“I think I loved Tommy as I’ve never loved anything since,” muses Dick. “Then one day my grandmother came to stay with us, bringing a quality cat named Omar. Tommy suddenly disappeared. I was told he’d ‘run away’ but I never could really accept that. It’s funny: About a year ago I was driving down the Freeway and after all that time, it suddenly entered my mind that Tommy didn’t run away—he was killed. Children sense what’s going on. Then they don’t trust their parents.”

A bothersome brat

Dick Chamberlain trusted his—up to a point. He was closest to his mother. with him all day at home, and whom Dick resembled in both temperament and looks. His busy dad was off early mornings, home late at nights and Bill, well, to him Dick was mostly a bothersome brat. Introspective Dick may not have considered his home the warmest in the world. Not long ago, in Jeff Corey’s house, his eyes wandered over the book lined walls and cozy disarrayed evidence of gemutlich living. “What a warm home you have,” Dick murmured. “Mine wasn’t like this.” And a friend observes, “Dick’s been complaining a lot about his childhood lately.”

Actually, family life at the Chamberlain’s went along about as it does everywhere—with successions of joys and small tragedies, calms and crises. Both boys had what they needed. in love and material blessings. They weren’t rich but there was always money enough. There were trips to family reunions. back to İndiana with the Chamberlain elan, to Northern California to visit the Bensons.

But he couldn’t share with his family, or anyone else, the secret dream he had clung to since his Fourth Grade and his favorite teacher, Florence Montgomery, had thoughtfully remarked. “One day I’ll look on a movie screen and see you, Dick.”

There was nothing unique about Dickie Chamberlain’s dream to become an actor. It was common, at one age or another, to almost every boy and girl in Beverly Hills. The town itself was one big such dream come true. Movies had made it and kept it flourishing. The studios were Beverly’s pulse and the glamorous stars its heartbeat. They lived up across Santa Monica Boulevard in mansions and on Wilshire you could see Lana Turner, Hedy Lamarr, Joan Crawford or a hundred other glamorous goddesses bustling in and out of the smart shops. At any corner Clark Gable might pull up in that curious new sports car of his called a Jaguar. Their lives were town gossip. as the lives of auto-makers were in Detroit, or rich tourists in Miami. South Elm Drive was like every Street in town. All around were people “in pictures.”

Dick’s paper route had names on it anyone might know. A friend’s father was an assistant director. Dick’s own family had a close friend who made “quickies.” And right across the Street in an apartment house lived a queenly beauty who was actually a star. Dick pestered her for autographs, week in and out. “I had to get new ones all the time because Billy would hang up the ones I had and riddle them with darts,” he explains. When the star moved out of the neighborhood Dick sneaked into her vacant apartment. The walls were covered with mirrors. “I think she must have had a Narcisstic complex,” he observes now dryly.

—KIRTLEY BASKETTE

(To be concluded next month)

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1963

AUDIO BOOK