The Truth About Hollywood Housekeepers

The truth about Hollywood housekeepers is that the two best in town are not ladies, but gents. A girl whom you probably never think of in this regard is the most imaginative. Equally the delicious doll you’d fancy would shed glamour over even a fried egg is a very low contender in the table-setting stakes. The broad truth is that when Hollywood housekeepers are good, they are very, very good. When they are bad, they are at least personally beautiful, but by and large they are simply indifferent.

By housekeepers Fearless does not mean party-givers. These latter are something else again, whipped up in equal parts out of money, caterers and the persistent urge for a big splurge.

No, by housekeeping is meant the daily living routine, that business of planning dinner every night and not too much chicken Sundays while you catch up on red points. It’s that stuff about seeing that the kids get to school on time; of making sure that after the laundry goes out, it also comes back; that the window sills are kept dusted, the cook kept happy and that life is made delightful for both family and friends.

Irene Dunne is a dream housekeeper. Due to the servant shortage, she no longer can have breakfast in bed, the only housekeeping luxury in which she used to indulge herself. Now she eats at table, morning, noon and night, but at breakfast her pad and pencil is ready beside her. She consults the cook on menus. They discuss the night there will be guests, the evenings there will be only “family.” Irene writes down menus, shopping lists and orders. She has days for everything; a day for upstairs cleaning, one for downstairs, a morning for cleaning linen closets, another for the windows. No food goes to waste in her spotless kitchen. The night after the Griffins eat roast, they have hash. Being devout Catholics, on Fridays there is always fish.

Everything for “Missy,” their beautiful child, is planned down to the final dot. Her vitamins, her naps, her playtimes are all perfectly balanced. Irene oversees all this, no matter how crowded her studio shooting schedule may be.

Decorated in a “French” mood throughout, the Griffin house is formal, and thus not very imaginative, but note that it is the Griffin house, not the Dunne residence. To guarantee that Dr. Griffin does not feel engulfed by an all-professional crowd, Irene sees her acting friends at the studio, Dr. Griffin’s friends at home. It works out wonderfully.

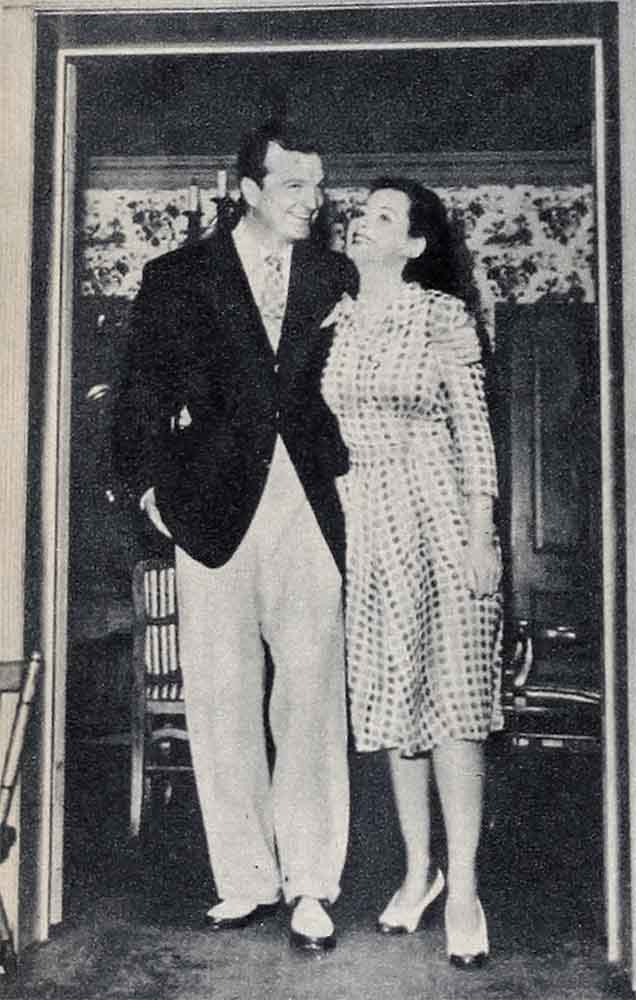

Jeanette MacDonald and Gene Raymond were certainly never equals in the box-office sense, but at home, before Gene was in service, there was always a feeling of complete camaraderie and equality. That “MacRaymond” tag was more than a play on words. It was, and is, a fact. Jeanette goes into the indifferent class of housekeepers and doesn’t give a hoot. Their house is big and casual. So, too, are the meals and service. Their food is very undistinguished, despite the production that Gene makes of “coffee diable” after dinner. Jeanette wouldn’t be the least surprised if you discovered dust on things. She would take it as a joke. But it is no joke to her that home is something to be lived in, at all times, in any manner so long as it is comfortable.

The Alan Ladds have this kind of casual housekeeping, too, allowing for everything being fixed around one personality. Susie lives for Alan. Alana lives for Alan. The servants live for Alan. Make no mistake on all that. Dinner may come on the table too early or too late, but nobody cares so long as certain menu rigidities are observed. Alan likes to eat red meat, so they eat red meat. Alan doesn’t eat lamb, so no lamb. Alan loves big, gooey desserts, so in come big, gooey desserts and give no talk, if you are a guest, that you are dieting and not eating desserts. You will. Alan will see to that.

Recently the Ladds redid their house. Alan wanted to move but they couldn’t find a place for sale and there is no renting in Los Angeles with the present housing shortage. So Alan, who was restless about Sue’s living against the background of former marriages, had to content himself with having all the colors, the hangings and the furniture changed.

They hired themselves an elegant decorator, so the results were elegant too: Effects like green velvet couches and sterling silver living-room lamps decorated with green trailing vines. Alan came home the night the living room was unveiled, took one happy look, then stretched himself down on one of those green velvet couches and put his studio-dusty feet smack down in the center of same. You know what Sue did? Her feet went down, right in the middle of the other couch. The Ladds beamed comfortably at one another.

Alan demands relaxed friends. He doesn’t like to go to other people’s houses, but he loves to have them come to him. So they do, and if you are lucky enough to have a Ladd friendship, you could drop hot peanut butter all over their expensive rugs and Alan and Sue would take it because you were a friend.

See Claudette Colbert on the screen and you see true chic—clothes, jewels, hair, make-up. So you think, what with her I being French, she is a perfect housekeeper. Are you wrong! She’s a terrible house! keeper. The whole subject bores her. She really likes only one thing to eat: Chicken. When she can’t put chicken on a menu she is stumped. Even when she can she says to the cook, “Dinner at seven. We’ll have chicken and you plan the rest.”

She invites the guests for seven, too, and if you don’t know better, you appear at that hour. Likely as not, Claudette is not yet home from the studio, or if she is, she hasn’t yet finished dressing. Before he was in the Navy, Dr. Pressman probably hadn’t got home from his office, either.

But about seven-thirty, Claudette, looking divine, runs downstairs—so showers you with charm you feel it was a privilege to have waited—and asks, very wide-eyed, “Will you have a drink?” It is an eternal surprise to her that guests will. She, herself doesn’t drink and she can’t see why anyone else does. She argues that liquor is hard on any woman’s face or figure, and with French logic, says, “So why take any?” It is perfectly vain to point out that some women find the indulgence socially pleasant. Face and figure before pleasure is her motto.

Still, she has a small bar in her playroom, but usually it is out of something: The olives for the Martinis or the soda for the highballs, or whatever. But finally the drinks get evolved and Claudette remembers that hors d’oeuvres go with them. So she rings for some. She hasn’t told cook to make any, so cook hasn’t. The kitchen goes into a spin, however, and just as the drinks get finished, hors d’oeuvres appear. Claudette now realizes that you can’t eat them without a drink, so the bartending flutter is gone into again and by the time the second round is poured, the hors d’oeuvres that should be hot are chilly and the chilled ones are warm.

Dinner may appear at eight, and it may appear at ten, and either way it will never be knockout, and Claudette, who worries about everything, will worry as to why it wasn’t better. One of the things she most admires in her closest friend, Mrs. William Goetz, is the manner in which the latter runs her home. Claudette loves her own home, aspires for perfection, but wishes she didn’t have to be bothered with domesticity. The truth is that she is an artist, with an artist’s temperament, and any detail that doesn’t pertain to her work, annoys her.

Even less naturally domestic is Barbara Stanwyck. Bob Taylor is a domestic husband, but since whatever Stanny wants is what he wants most, eventually it works out okay. For example, Bob loved their estate out in the Valley, but Stanny didn’t go for the space, quiet and horses. So they moved into town. Bob had just got settled down into liking the new place when Barbara again craved change. They then bought a compromise place in Coldwater Canyon, half city, half country. They got in a decorator who went wild with color and the result was stunning. Bob loved it all. But nervous Barbara, the moment he went into the Navy, up and sold.

Besides their great love for one another, the Taylors have two other enthusiasms very much in common: Steaks and coffee. They’ve heard teli that there are other things to eat and drink, but don’t bother them. Steak and coffee is their stuff. Stanny considers twenty cups daily par and then wonders why she suffers with insomnia. She drinks nothing else ever. The Taylors do not give dinner parties and their house, wherever it is, is run by remote, pretty good servant control. When they entertain, they go out, usually with Jack and Mary Benny, to some night club where they have steak and coffee.

Recently a climbing Hollywood hostess was very set up about corralling this foursome for a dinner at her home. She had her chef, who is really superb, work up his most de luxe, delicate specialties.

Out came the meal, down went the f guest-of-honor faces. The portions they m took were infinitesimal. Finally they confessed, practically in a chorus, “We never eat anything but rare beef.” The hostess didn’t cut her throat; neither did the chef, but a good time was had by nobody.

Here are three ladies who do their housekeeping with real flourish. Mal Milland does it must luxuriously, Lillian MacMurray does it most devotedly and Ann Sothern Sterling does it most deceitfully, but the result in all three cases is as nearly perfect as wartime living will permit.

On screen, Ray Milland is a comedian, but at home his English hankering for formality is manifest, and Mal, his beautiful wife, sees to it that it gets full expression. There is never a flick of dust anywhere in her exquisite rooms. Her meals are served perfectly and punctually. Her handsome son Danny is perfectly brought up, has glossy manners and usually is dressed in the same grays she personally affects. Superficially, Mal Milland seems hail-fellow-well-met. Actually, she reserves to herself the right to know only the most correct people.

Lillian MacMurray’s household and housekeeping is run, like Sue Carol Ladd’s, for the gentleman in the house. But it is not casual. Rather it has all the orderly refinement of a minuet. Fortunately Lily and Fred share tastes in common. They both like what can only be described as formalized informality, comfortable but very valuable American antiques, not fancy but perfect food, a garden productive of super vegetables and super flowers, and no weeds or snails tolerated. Every piece of china, every pane of glass, every chair, table and whatnot in the MacMurray house shines. They go in for small parties, but when they have an occasional large one, that is done with correctness and gusto, in a circus tent put up over the entire garden. Little Susie MacMurray lives according to a very proper, healthy schedule. Lily makes most of her tiny dresses herself. Even the chickens which Fred raises live in a spotless henhouse, safely off the ground, each hen in a separately marked cubicle bearing her own name, with her own feed, her own water in her own cup; while they are hidden at the end of the garden, they get a nice view of the swimming pool.

Admiring Mal and Lily so much, Annie Sothern tries to live up to them, but can’t quite. Like Colbert, that’s the actress in her, that and being so busy. Ann’s homes, while small, have always been exquisitely decorated and maintained. Her meals are gorgeous, even if she herself can’t boil an egg. When she entertains, which is frequently, she passes up her own delicious victuals, explaining that she is dieting. Since her friends are all old friends, and devoted, they never crack a smile. They all know, however, that Annie has been smuggling herself candy all day long.

Probably income taxes primarily and now the war have forced the trend toward simpler Hollywood living, but there are only two stellar houses in today’s Hollywood that can be called opulent. The younger set, Garland, Turner, Johnson, Jones, Walker, De Haven, Allyson, tend toward apartments and night clubs. But there are two present-day star households where the word opulence still applies (plus those two perfect male housekeepers who have opulent homes also).

Greer Garson lives opulently amid twin grand pianos in a green-velvet-couched, brocade-hung living room, complete with modernistic art, cabinets featuring corals and pink sea shells and a broad gray staircase where the lights are so arranged that Greer always has dreamy backlighting on her red hair as she descends upon her waiting guests. And they do wait. Time means nothing to her.

There is a Garson butler. There is a Garson parlor maid. There is Mother. There is a secretary. When on Navy leave, there is Richard Ney, a charming, handsome husband. The food is very British, which means not too good but served with great drama. The wine is also British, which means not very heavy nor very expensive sherry. Miss Garson—and one thinks of her that way, were she married ten times—entertains practically none, but when she does it, it is distinctly she who is entertaining, not Mother, not Richard.

The other opulent home? Joan Bennett Wanger’s. She is the perfect housekeeper, the girl who combines daily living into something so alluring, so imaginative, so subtle that the most hardened bar-fly would want to settle right down by her fireside.

You know how Joan always looks: Very pretty, very chic, very gay, very wise. She runs her home like that. Everything in Joan’s house is dusted, shining and orderly, but you have no sense of fear about moving chairs, putting your feet, if you must, on the coffee tables or dropping ashes on the rugs. The Bennett-Wanger meals are masterpieces since the lady knows not only vitamins and calories, but sauces and wines. Her meals are served punctually but so well planned that if guests are late or linger overlong over cocktails, they are still not spoiled.

She has three daughters by three husbands, all at very varying ages, all beautiful, clever and gems of deportment. Joan not only plans all their meals with positively medical regularity, but she oversees their gland shots, if such are needed, their tooth braces, their diction lessons, their clothes fittings, their hair-sets and their French and dancing. This may sound like exaggeration or as if the kids had no fun. It is no exaggeration. It isn’t possible to exaggerate what a good mother Joan is, and as for the kids, they live in a continual, if very polite, world of laughter.

If you want an example as to how Joan’s imagination as a housekeeper functions, consider this: One night some unexpected guests came in and there was nothing in the house for dessert save watermelon. That seemed dull to Joan until she thought of pouring champagne over it. Another time, she decided on an all-green color scheme for her dining-room table. It was winter and there were no green flowers. So she got calla lilies and green make-up powder, patted the lilies into an entrancing green, scattered some gold dust on them and enchanted her guests.

Can two mere men top that, you ask? Yes, Adrian, the dress designer, married to Janet Gaynor, and Arthur Hornblow, the producer and ex-husband of Myrna Loy. Adrian, who is as superlative a decorator as he is dress designer, can dramatize a simple dinner into an event that must make Nero whirl in his grave. Before the war, when nonsense was permissible to those who could afford it, Adrian used to do things like having real pearls served on the exquisite half-shells he used for finger bowls. Janet leaves all details to him and their house is run flawlessly.

Arthur Hornblow’s dinners are famous and bids to them eagerly sought. He makes as much ceremony out of opening exactly the right bottle of wine as most cities make out of unveiling a public monument. An example of how delightfully he does things is the story about the time he was trying to re-woo Myrna who had just left him. They had rented the house in which they had been so happy together, but Hornblow sent for the decorator who had done it and had him whip up—for one evening, mind you—an exact duplicate of the room Myrna had most loved, a duplicate perfect down to the smallest ash tray. Then he served a dinner composed only of her favorite foods. There was a brief Hornblow-Loy reconciliation, remember? Guess when it happened.

And finally, the booby prize! It goes to that beautiful, gay, delightful creature—Miss Hedy Lamarr!

Does she know what she’s eating? No. Does she know what time any meal is served? No. Does she see that things are picked up, the water changed on the flowers and the master’s slippers waiting before the fire? No.

What does she consider a dandy dish? Bologna. That or pressed ham. In sandwich form, made of thick, usually lopsided bread. No lettuce. Not much butter, some mustard and—here it comes, kids—with the rind or casing or whatever you call that non-chewable stuff that coats bologna, still on it. The chances are very good that this is what you’ll get when you eat with Hedy.

And does it matter when you look as Hedy does? No.

But at least you know the truth, now, about Hollywood housekeepers.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1945