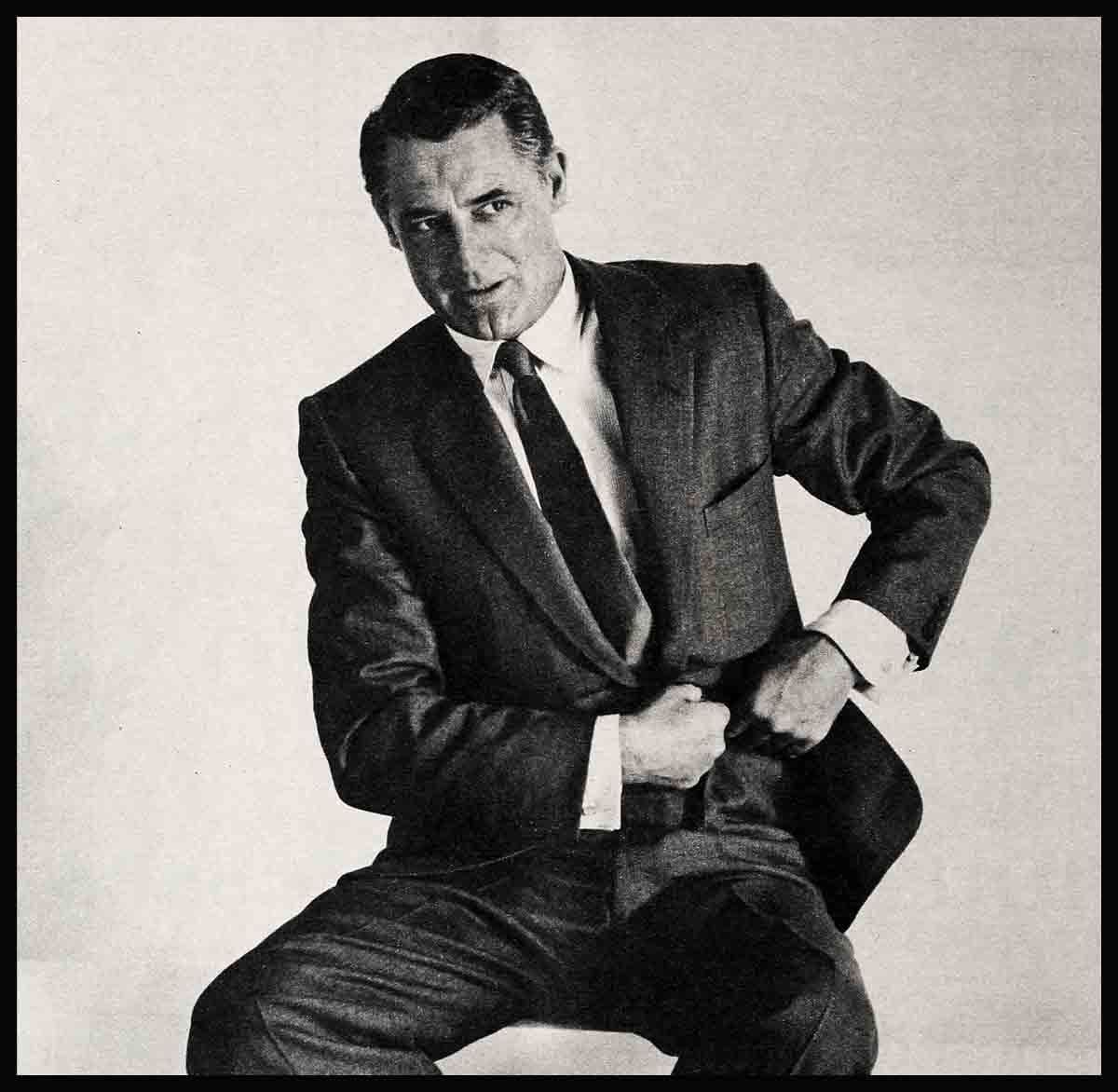

Cary Grant—Confidential File

FROM: Sara Hamilton—Hollywood

TO: New York office

SUBJECT: Cary Grant

I didn’t get the story you wanted on Cary Grant. In fact, I didn’t get any story at all. You see, what happened so threw me off base and into some sort of funny breaking-out spells, I never got around to it. But I thought I’d better send these notes on to you since I hear Cary may be leaving Hollywood for good.

Anyway, it all began when I telephoned Cary’s own Granart Production Company, expecting, as one always does, to go through various channels, stone-deaf secretaries, vice presidents in charge of utter frustration, and what-not. And, although—Cary is a friend and hot like anyone else in the whole world, know how busy these producer-actors dare and so, at best, I hoped for an interview come next May Day.

Nothing of the sort happened, though. Cary came right on the telephone when he heard my name and literally surprised me into idiotic mutterings. “Hello, Sara dear,” he greeted me.

“How are you?” I asked him. him the idea for the story.

“Come and see me,” he said.

Now, if all this seems routine and normal for Hollywood, it isn’t. In truth, there is no other star of Cary Grant’s magnitude—and that’s way out there, daddy-o—who can be reached by telephone and by personal contact, as easily, as cozily as Cary. By those who know him, I mean. And I’ve known Cary for, oh, at least 25 good years.

So we sat in his dressing room talking, when Cary suddenly revealed his hopes. “I want children,” he confessed. “I want children, a home, a wife and fatherhood to fulfill my life.”

Perhaps those weren’t his exact words, but almost. And, as I sat there, looking at this friend I so greatly admire, I realized this man was starving—literally starving—for the things other men, in less glamorous professions, take for granted. For children who will love him and who will fill his life to overflowing.

And bear in mind, Cary is far from the off-with-the-old-love-on-with-the-new type.

He was devastated when actress Virginia Cherrill called a halt to their marriage of less than two years, and later moved on to become the Countess of Jersey.

He poured out his disappointments to close friends when Barbara Hutton walked out to become a baroness and to learn, too late, that Cary was the best husband she ever had and the only one who wanted nothing from her. Cary, himself, was earning a fabulous salary, for those times, and wanted only to give.

He still hasn’t completely let go of Betsy Drake, even though the formal announcement of their separation is now history. In fact, it was Betsy who met Cary at the airport when he returned from that trip to New York.

But, you see, each of Cary’s three wives filled a need in his life whether he realized it or not. Virginia Cherrill gave him his first home after years of roaming an insecure world as a bachelor and struggling performer. He emerged from the Barbara Hutton marriage a polished man of the world and also one well aware of the pitfalls of an idle, glittering existence. And Betsy Drake came into Cary’s life during his most important period—the transitional era. He had begun, by this time, to seek, to probe, to search within himself, to find out about himself. And such a thorough, honest probing can be darn painful. And how many people do you know in this world, who take time to find themselves? Especially successful and famous people such as Cary Grant? Very few, eh?

When it was all over, Cary made a discovery. He had come full circle in his life and now finds himself at familiar crossroads where he stands as lonely as the man he played in that midwest cornfield in the movie, “North By Northwest.” A man just waiting. Just waiting for his life to be fulfilled by the one right woman.

From all signs and omens, I personally believe the girl he’ll choose will be as young as springtime, as delightfully surprising as violets in February and as home-loving, family-raising as any man could want. But maybe I’m just wishing on a star for my very old friend.

He adored Betsy. Pride in her intelligence fairly oozed from him. So who’s to say what brought about their separation a year or two later? Personally, I think it was merely the simple process of evolution. They emerged from their studies and pursuits of hypnotism, Yoga and philosophy, only to find themselves two separate individuals, heading toward opposite poles.

Betsy’s life is one of books, of painting, of study, of writing. I’m told she alone wrote the film “Houseboat” in which Cary and Sophia Loren starred. One day, with great pride Cary read me a paragraph or two from a letter Betsy from London. It was filled with warmth and beauty. “Why, these two are the deepest of friends,” time.

I believe her the shipwrecked Andrea Doria nightmare that stripped them both of any outer pretenses, revealing themselves to each other as two people destined only for a lifelong friendship. For, just as after that Betsy’s life took a turn to the creative, Cary’s took a sudden swerve to the domestic. Toward the craving for home and children. Toward that lonely crossroad where he stands today. Waiting.

I can’t remember the exact year I first met Cary—sometime in the early thirties—but I remember the place. It was in the old publicity building on the Paramount lot. Three tall young men were standing talking together, at the end of the hallway, and a publicity girl, who was with me, guided me in their direction.

“I want you to meet these newcomers who will certainly become stars,” she said, introducing me to all three, one of whom was Cary. And this is just awful, but I can’t remember who the other two were.

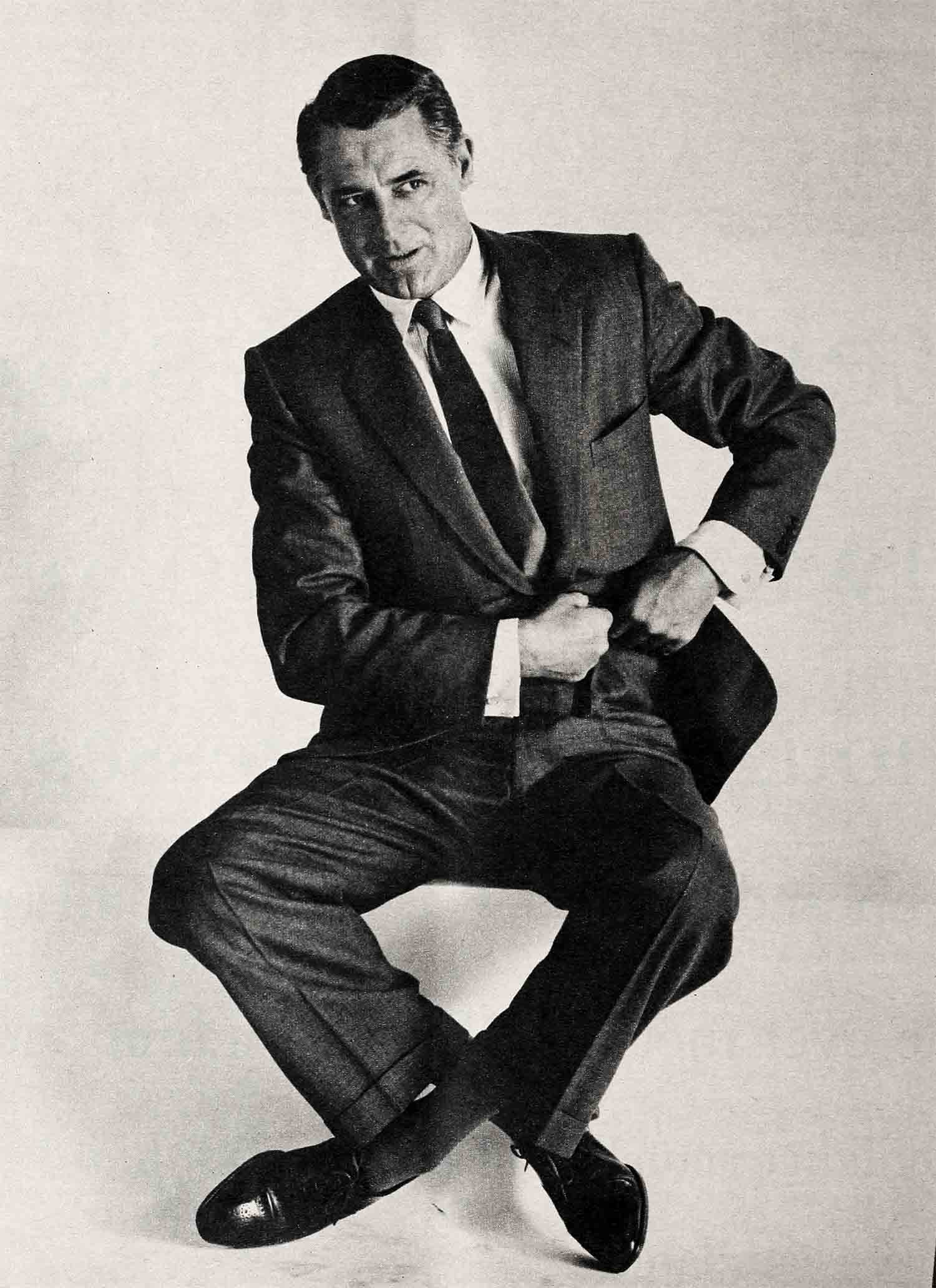

But I remember Cary well. Tall, dark, handsome, with a voice a little like a set of chipped dishes, Spode china of course, and I noticed that he approached everyone sideways, like a lateral wave along the shore. He still does in movies, if you’ll notice. It’s part of his charm, I think.

I was amused when he was given the role of the Mock Turtle—the character, not the soup—in “Alice in Wonderland.” And I was intrigued when he became the young man of Mae West’s invitation—“Come up and see me sometime.”

It was after Cary created a sensation in such comedies as “The Awful Truth,” “Bringing Up Baby” and “The Philadelphia Story,” that I ran into him again. “Look,” he said to me, “bring Sally (my teenage daughter) over to the set and we’ll have a laugh and a cup of coffee later.” He was making a picture, with Ginger Rogers at the time on the RKO lot, and frankly, I was a bit skeptical. Ginger, in those days, was far from friendly toward any visitor—press or otherwise.

Anyway, Cary had seen to our passes and a publicist was waiting at the gate to escort us to the set. Cary, a delightful and eager host, came forward immediately and found us comfortable seats. But, during a scene rehearsal just a few minutes later, orders came for us to leave the set immediately. Miss Rogers, I was assured, appreciated no visitors. In vain, I protested, explaining I was a member of the press and also a personal guest of Mr. Grant’s. It was no go. “Out” was the word from Miss Rogers and so, in order not to create a commotion, my daughter and I rose quietly and left the studio.

Cary caught up with us at the publicity department. He’d run every step of the way, in makeup and out of breath, just to apologize. There was nothing to be said, of course, but I think the incident perhaps more firmly established our friendship. He was such a gentleman—so sincere in his ways.

A few years later, at a party at the Jules Steins’ (he’s head of MCA so it was a star-studded affair), Cary, the late John Garfield and I found ourselves a threesome on the patio. For some reason, I’ll never understand, I suddenly started telling a funny story that I realize now, in thinking back, wasn’t terribly funny at all, but nevertheless simply fractured Cary. I remember him wiping away the tears of laughter, and I thought to myself—this person wants so very much to laugh, to enjoy himself.

In each instance, you see, I was learning more and more about him. His kindness, his thoughtfulness, his eagerness for enjoyment, all helping to make me understand his present longing.

He was moving right along in the world of glitter and gold by then, already a firm friend of the fabulously wealthy Howard Hughes of the New York and Hollywood smart set. He’d progressed from what I believe to be the best light comedies ever made, bar none, to such compelling dramas as “Suspicion,” “None But the Lonely Heart” and “Notorious.” Pictures that, for some reason, won everyone Academy Award nominations but the star himself. The man who only contributed to their greatness.

He was deeply immersed in romances, from time to time, and oddly enough the girls he fell in love with were mostly of a type. Blond beauties. And heavens above, how they fell for Grant! And no wonder. For all his fame and good looks and charm, there was still something basic about him that was terribly endearing, and yet he couldn’t seem to hold onto marriage.

I recall the preview of his picture, “The and the Bobby-Soxer” at the Academy Theater, when Cary came in un-expectedly and requested the person in the seat next to me to move over. “I want he explained.

They tell me it was a good movie. I wouldn’t know. I was so fascinated with Cary’s almost naive enjoyment of the proceedings, that I couldn’t concentrate on the movie. “There’s a very funny potato sack race scene coming up now,” he’d tell me, always drawing attention to other players in the story while I thought to myself, “And this is the very sophisticated Mr. Grant.”

But let me hasten to add there is that side of him, too. The sophisticate—I ran head-on into it one day when he was making “Kiss Them for Me” and I’d gone out to his dressing room for coffee. Only Cary took Sanka with vitamin A—or was it C—pills.

Anyway, Suzy Parker was in the throes of this, her first movie, and not doing too well. So, in typical Grant fashion, Cary had invited her in for a chat. A chat? It was a verbal onslaught with Cary suddenly feeling the need to “explain” Suzy. “She’s terribly bright and misinformed,” he said by way of introduction. “But she does know a lot about penguins. She really does.

I slowly digested this highly fascinating piece of information while Suzy, who never paused for a breath, went right on talking through Cary’s conversation.

“She has a facade like Grace,” Cary observed, more to himself than me, but I knew, of course, he referred to his close friend Grace Kelly, Princess of Monaco. “But,” he continued, “she’s innately honest, like Ingrid.” All the while, Suzy talked on. “But I think—” Cary continued.

Suddenly, it was as if Hades had broken loose. With his robe over his costume, Cary was at the door, belaboring a dumbstruck set worker who had dropped a chewing-gun wrapper outside Cary’s dressing room door.

“Pick it up,” he ordered. “I can’t stand litter.”

“This happen often?” I asked, when order had once more been restored.

“All the time,” he admitted. “I even lean out car windows to yell at people who throw things on the street. Just can’t stand it.”

In view of later developments, I never quite got up the nerve to ask Cary what he thought of Suzy’s “innate honesty” now. Suzy, who had, at that time, denied the existence of a husband.

Oh well, it’s so much Sanka under the bridge as far as Cary’s concerned, I’m sure.

At the time of this get-together, I learned that Betsy was making a film in London and Cary, who had just finished “An Affair to Remember,” with Deborah Kerr, had bought his wife a gift. Deborah, who was leaving for London shortly, had agreed to take it with her. “Do you think this note is all right?” Cary asked, handing me the message he’d written Deborah.

The note was a charming, warm gesture to a warm and charming friend.

I think, too, Cary falls a little in love with each of his leading ladies. Which is natural. In each, he finds something to admire. In a few, he finds and gives staunch loyalty.

It could be my imagination, of course, but with Cary I sense, lately, a letting down of the bars. He’s taken to mingling more with Hollywood friends. Not just the inner circles of Hollywood but with the workers, the doers, the earthier. As if he were slowly but surely coming home again. Which, I think, is somehow a good omen.

It’s odd, too, but in Cary people have a way of seeing the reflection of their own ideas. Right now, I’m willing to bet there are a dozen different Grants in existence. Each, the product of another’s creation.

The adoration and hero-worship lavished on Grant by Tony Curtis is, of course, well known. His walk, his talk, his clothes are, to Tony, the living end. In fact, it was Cary’s accent Tony affected through part of his sensational movie “Some Like It Hot.”

Many men regard Cary as a model of fashion with impeccable taste in clothes. A young actor friend once regaled me for hours about a waistcoat and scarf Cary wore in “To Catch a Thief.” “What waistcoat and what scarf was that?” I finally asked, to the lad’s complete and utter disgust.

All I know about him and the clothes, for which he is famous, is that in his white tie and tails—as he steps out onto the stage of the Academy Awards Theater—he outshines every male within miles.

I see Cary in an altogether light. Incongruous as it seems, I find him the friend who, above all others, I can go to with a spiritual problem and find complete understanding. I can tell him what is in my heart, and he responds. I can confess hopes, and receive encouragement.

In return, I clearly understand his yearning to have a whole and complete life in a home, in a settled happy marriage and above all, in parenthood. And maybe it’s just a hopeful hunch, but somehow I feel these coveted attributes are just around the corner for Cary Grant. Perhaps, for all we might know, in the year 1960.

And wouldn’t that be a happy day for all who wish him well? Eh?

—Best, Sara

BE SURE TO WATCH FOR CARY IN “THE GRASS IS GREENER” FOR UNIVERSAL-INTERNATIONAL.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1960

No Comments