Paul Anka And The Barefoot Princess

The day he stepped off the jet at San Juan’s International Airport in Puerto Rico, it all came back to him. The flower-scented air, the clear hot afternoons, the breeze from the ocean, the tall skinny palm trees. The signs in Spanish and English. The crowds. The heavy police cordon surrounding him. How much the same as this time last year—with the one terrible exception.

The man from the hotel who’d come to meet him told him, “Last week it was the President of the United States, this week it’s Paul Anka. I don’t know which of you we had to protect more closely. Do you realize there are at least a thousand teenagers—behind the fences, behind the lines. They’ve been here all afternoon, trying to find a way to the ramp. We’ve got to get you out of here or you’ll be stuck for six hours.”

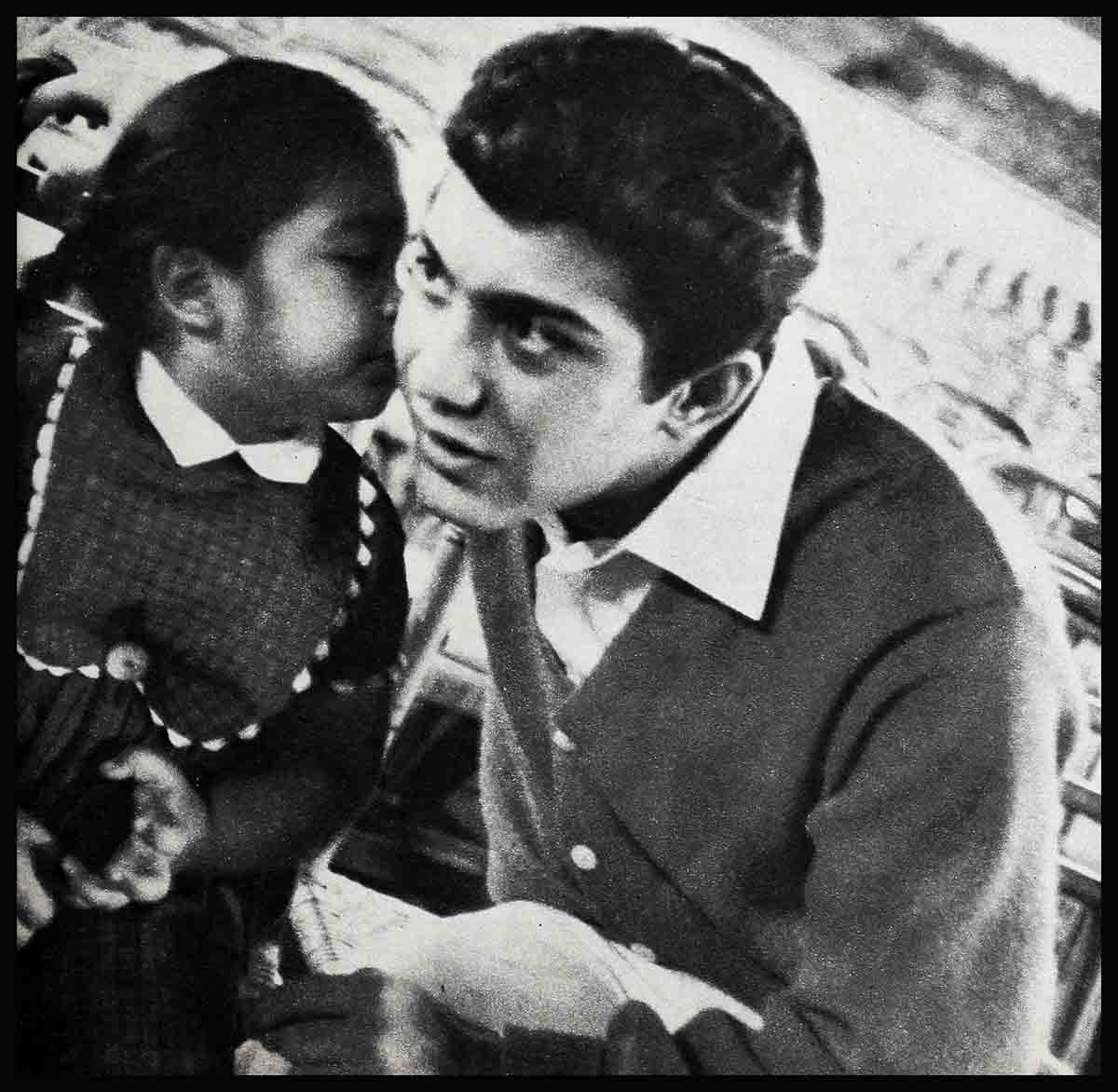

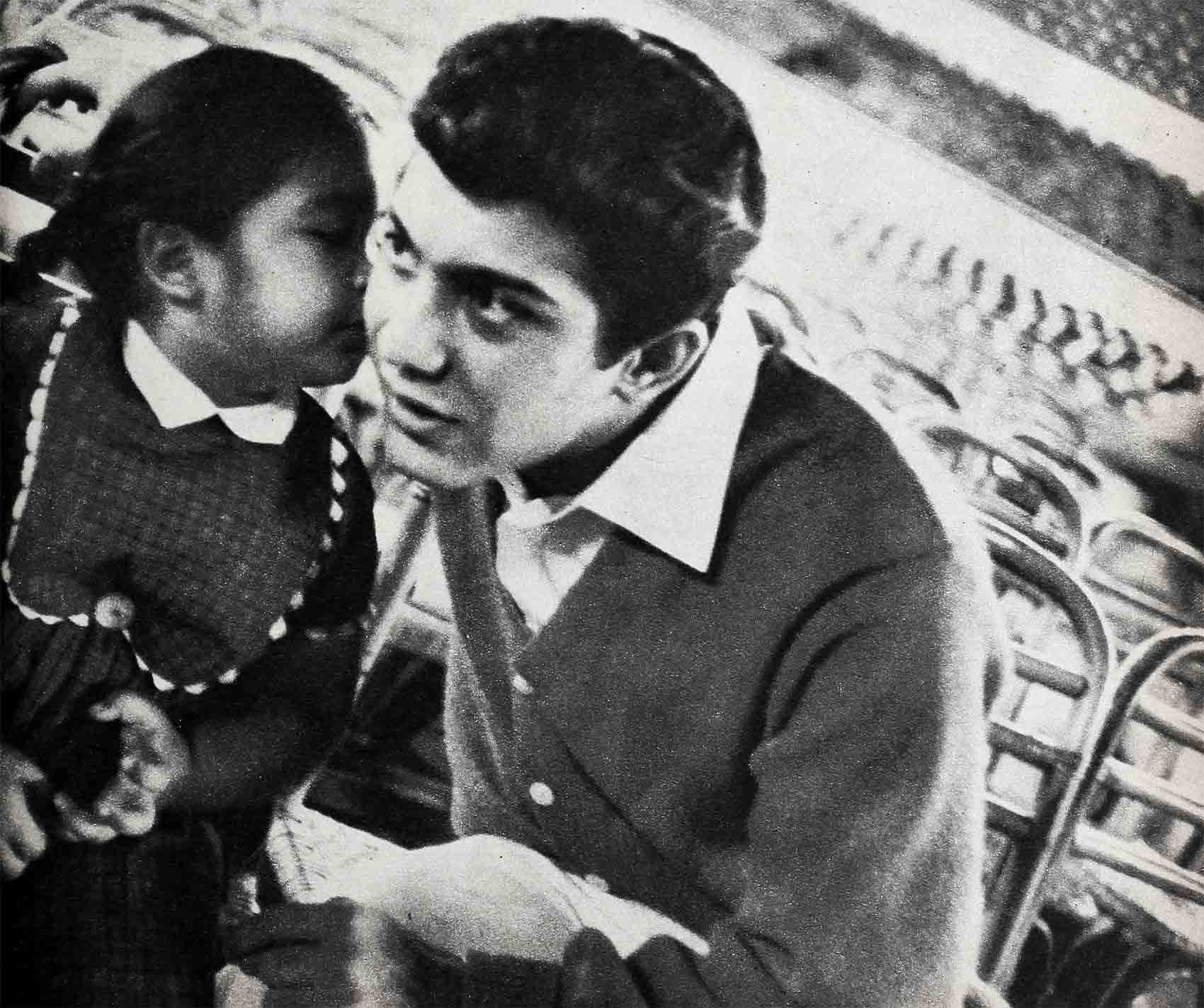

He’d always tried to give his fans a chance to see him, and ruefully said, “I hope they don’t mind.” Suddenly about twenty of them broke through and rushed toward him. The cordon tightened. “No autografos ahora” (“No autographs now”), the police shouted. One very young girl with big brown eyes both scared and shining, wearing a faded red dress that looked as if it were made for someone else—yet clean and starched—and a red ribbon in her black hair, protested to the policeman, “No quiero un autografo. Tengo una carta para Paul Anka.” (“I don’t want an autograph. I have a letter for Paul Anka.”) She ran up to Paul and put an envelope into his hand. “Para Usted,” (“For you,”) she said softly, and disappeared. In the next second he was ushered into the waiting car and off to the hotel where he would be performing for the next two weeks. Late that night he went to his room and locked the door and stood at the open window, listening to the surf pounding below, to the music from the Club Caribe, where the act preceding his was finishing up. Under the colored lights of the gardens, pink flamingos strutted among the palm trees, and the ruins of old Fort San Geronimo still guarded the Island from the sea. Tomorrow he’d open. It would be a rough one. Because the contrast with last year was a rough one.

He started to hang up the jacket of the suit he had worn on the plane—and then he remembered that little girl at the airport, the note he had hastily shoved into his pocket. He took it out.

It was a clipping in Spanish, dated several weeks before. He didn’t know much Spanish, but so many words were like English he could make out that the article was about his coming appearance. It said that this appearance would be a memorial to his mother (memorial . . . concerto . . . a su Mama), who had been with him at this very place one year ago, and who had so sadly died shortly after, so young.

He was taken aback. He certainly never meant to imply that; he could never commercialize on a precious memory. His performance here certainly wasn’t being billed that way. And yet, of course, it was true. But he would never let on. never talk about it. His feelings were not for publicity. He had thought he’d like to do something to honor her memory, but what could he do that wouldn’t be ruined by a lot of phony sentimentality that would really hurt?

There was a pencilled note with the clipping: “To Paul Anka, My English is not much. I am sorry about your mother. Welcome to Puerto Rico. We like you here. I will not see you because night clubs are for rich. But I listen your records and glad you are here. Please be happy here.”

That was all. He stared at the note in his hands, remembering. He had. months ago, learned to accept his tragedy with, “It is fate.” The pain of his bereavement had eased; it didn’t help to think too much. He had determined to be like his father, who never showed his heartache in front of the children.

He thought about that shy little girl in the old red dress, who hadn’t wanted to bother him for an autograph, who wanted only to tell him that she understood. He tried now to recall how she looked. There was something different about her—but what was it? Suddenly, he knew! She’d been barefoot!

Kids, he thought. Kids—wherever they are, the world over—I love them.

A long time to want

“Kids, I love them,” Paul Anka repeated to me over his shoulder as he recalled the story. He had gotten up to answer the door to Numero 1302, his suite in the hotel where he was playing now.

A waiter came in with two pale frothy pineapple drinks. He’d be back with the hors d’oeuvres.

“When are you going to have kids of your own?” I asked Paul. He had his answer for me.

“In about ten years from now, I’ll just be getting around to getting married.”

“That’s an awfully long time to wait.”

“Getting married too quickly is a form of security for some. I am a secure person. Happy. Contented. Of course I have my off moments like anyone else. But then I go to my room, lock the door and sit down at my piano. I have no entourage like some. Only my road manager, my manager and four musicians. No high school buddies! The ones who travel with an entourage—well, probably they need it. Everyone around saying, ‘Yeah, you’re right!’

“Marriage? Now is not the time for it. I think it’s important to date many people before settling down. In fact,” he went on, “that’s what’s wrong with so many marriages. Girls should know who they want to love, how they want to be loved. They’ll think they’ve fallen in love with Billy Brown next door, then they get to college and realize that Billy Brown’s not the one.” He added thoughtfully, “I know you’re supposed to love your parents and all, but my own parents—I’d like to have a marriage as good as theirs was. They were really very, very happy. And,” he added, leaning toward me earnestly, “my father is really a wonderful, wonderful man.

“You know he even taught me to cook. When Dad had the restaurant, I worked in it. I cook and I love it. So does Dad. Regular dishes, though. I left the SyrianLebanese specialties to my mother. My specialty is—I can make a good breakfast, lunch, dinner! And I’ll teach my kids, too.”

“How many kids would you like?”

He grinned. “Loads! I love them.” Then, as an afterthought, “I guess I’d better tell the girl I marry!”

The front door opened and in walked a cute teenager, Paul’s nineteen-year-old sister Marion. He had invited her to spend a few days in Puerto Rico before going back to secretarial school. Ever since his mother died, he tried to spend what time he could with Marion. She’d been sightseeing in Old San Juan that afternoon and began telling us the wonders of Calle del Cristo, that centuries-old street of the shiny blue cobblestones. The flowering trees, the singing fountains, the sudden whitewashed alleyways beckoning to a Spanish colonial garden patio, the cool arches, the dark mahogany carvings, the ancient silver altar at the southern end of the historic street . . . she saw them all.

Last week Marion had been visiting her aunt in California, then had stopped off at home in cold, damp New Jersey. The abrupt changes in climate had given her a sore throat. Her conversation was punctuated by an occasional cough.

Paul got up and went to his bedroom. “Here, take this,” he told her, very authoritatively, handing her a packet. “It’s a special kind of aspirin. Bang it till it’s crushed. Gargle with it.” She started to walk out with the medicine to her own room and Paul, very much the Big Brother, called after her, “Take some hot tea—” she said thanks and goodbye and closed the door, “—and some honey.”

He came back to the long, low sofa again, saying, “She’s a good kid, Marion, My little brother, too—Junior—Andy. The best thing that ever happened to me, I’d say, was being born. But the best present I ever got handed to me was when Junior was born.

“You must have been about ten years oId then. So often kids feel a little jealous of a new baby. You weren’t?”

“Oh, no! The first time I saw him, everyone stood around the bed admiring him. We pampered him, we made him the pet of the family. We’ve always been very close. In fact, I taught him to walk. He wouldn’t come for my mother or father, I remember that day so well. . . .”

Those first steps

“Come to me” the boy crooned softly to the baby. “Come, Junior, come to me.” Paul was down on his knees, his arms outstretched. Andrew Anka, Jr., though he didn’t know it yet, was about to take his first step.

The baby’s bright eyes were on the shiny red apple Paul was holding out to him. He held tightly to the safety of the big chair in the corner, but that apple was edging away from him. One little hand reached out. Paul took a bite, very deliberately, and encouraged, “Come, get the apple, Junior, you can do it, you can walk.”

One tiny foot moved uncertainly. Paul backed away a bit. “That’s right, Junior, come to me,” and suddenly the baby tottered ahead, walking his first steps into the arms of his loving big brother. . . .

Paul took another sip of the pineapple drink, still smiling at the memory.

“Is Andy going to follow you in show business?”

“No!” This was very definite, very serious. Then Paul laughed, almost like an indulgent parent and admitted, “Junior wants to, though. He’s fascinated with it. He’s just crazy about all the girls. At twelve years old! He sees only one side of it.” Very serious again, “You have to be made of pretty strong stuff to sustain; you really must love this business. But I enjoy the pressure.”

“Are you having any fun down here?”

“To tell the truth, I’m trying to get a little rest while I’m here. You know I have an extra show every day—a luncheon performance, so I’m trying to cut down my personal appearances. I’m not going to do too much this time. Last year I made a personal appearance in that department store and the fans wrecked the place. I had to be rescued by helicopter. I don’t think they’ll want me back.

“When I get back to New York, I have to cut a new album for RCA. I’ve got to find time to rehearse. And I’m trying to get some sun now.” (He already looked as if he’d been on the beach for months.)

The waiter came with the hors d’oeuvres and we devoured them. “I always gain weight on a tour,” Paul said, reaching for one more, “eating like this.”

I started putting away my notes. Paul wondered if I could tell him something before I left. Had I ever read that publication, the one the clipping came from? I’d never seen it on a newsstand, but I’d heard it was a small religious publication, not circulated too much in this section of town.

Time to go. “Goodbye,” I said, “don’t work too hard.”

“I’m trying not to,” he said. “See you on the beach.”

And that was his intention, not to add any extra appearances. To get some rest. For the next few days, when he wasn’t performing or rehearsing, he’d snatch some sleep or get some sun.

But one morning at the end of his engagement—his sister had already gone home—he got up early and decided to see San Juan. By cab, it was less than ten minutes from the hotel. They approached Munoz Rivera Park, where a couple of small boys, with bare feet and cheerful faces, waited to board the bus and sing their serenade to the sehores y sehoras of the guagua (bus), accompanying themselves on instruments they’d made from bits of tin and wood.

The next moment they were roaring along the embankment road along the north shore, past the Police Athletic League, past the boys playing baseball, the men surfcasting, the few hardy skin divers. The cliff was steep; on the left, the beginnings of the city, on the right, a sheer drop to the turbulent Atlantic Ocean, wild and beautiful.

At the massive castle of Fort San Cristobal, Paul thought of getting out of the cab and enjoying the fantastic view when, a few yards further, they came upon an unexpected sight. Houses, many houses, huddled together down that steep cliff to the ocean. Built of rough boards, many unpainted, many up on stilts, the windows shuttered with wood. They were old houses—not centuries old like the strong solid buildings across the road—but old shacks.

The top of the grassy slope was marked by stretches of the original city wall. A few straggly wild flowers bloomed around it. Dozing there in the morning sun was an old woman, a transistor radio blaring in her lap. Near her a group of barefoot children were laughing and dancing the twist. Part of the hill had been leveled for a court and barefoot boys were playing ball with a piece of cork.

“La Perla”—the slum

“This is, unfortunately, La Perla,” said the driver. “Our slum.”

Paul had seen poverty all over the world. He had seen the conditions under which many of the Puerto Ricans who came to New York lived. La Perla was shabby, yes. But there was sunlight, the fresh air, the ocean below.

“Nine thousand people are crowded here,” said the driver. “In America they are called squatters. No one owns this land—I mean, there is no landlord. It is public land. Puerto Rico’s land. Many years ago poor people would come here and. finding a space unoccupied, would build themselves a simple place to live. There will one day soon be a slum clearance. and these houses will be gone. The people do not want to leave. It has been their home for so long.

“Perhaps you think it does not look like a slum. I have seen slums in New York myself. It is not like that. But it is a slum, nevertheless. Our biggest. The ocean is not for swimming here. These people are very poor, many are sick, many cannot find work, there is often not much food, and worse, not much hope, not much chance. Many have not been even as far as the hotel where you are singing. For many, they will never see anything but La Perla, their whole life.”

Some have gotten as far as the airport. The thought suddenly just popped into his mind. There was something he could do for his mother—and for a little girl who had made it all the way out to the airport.

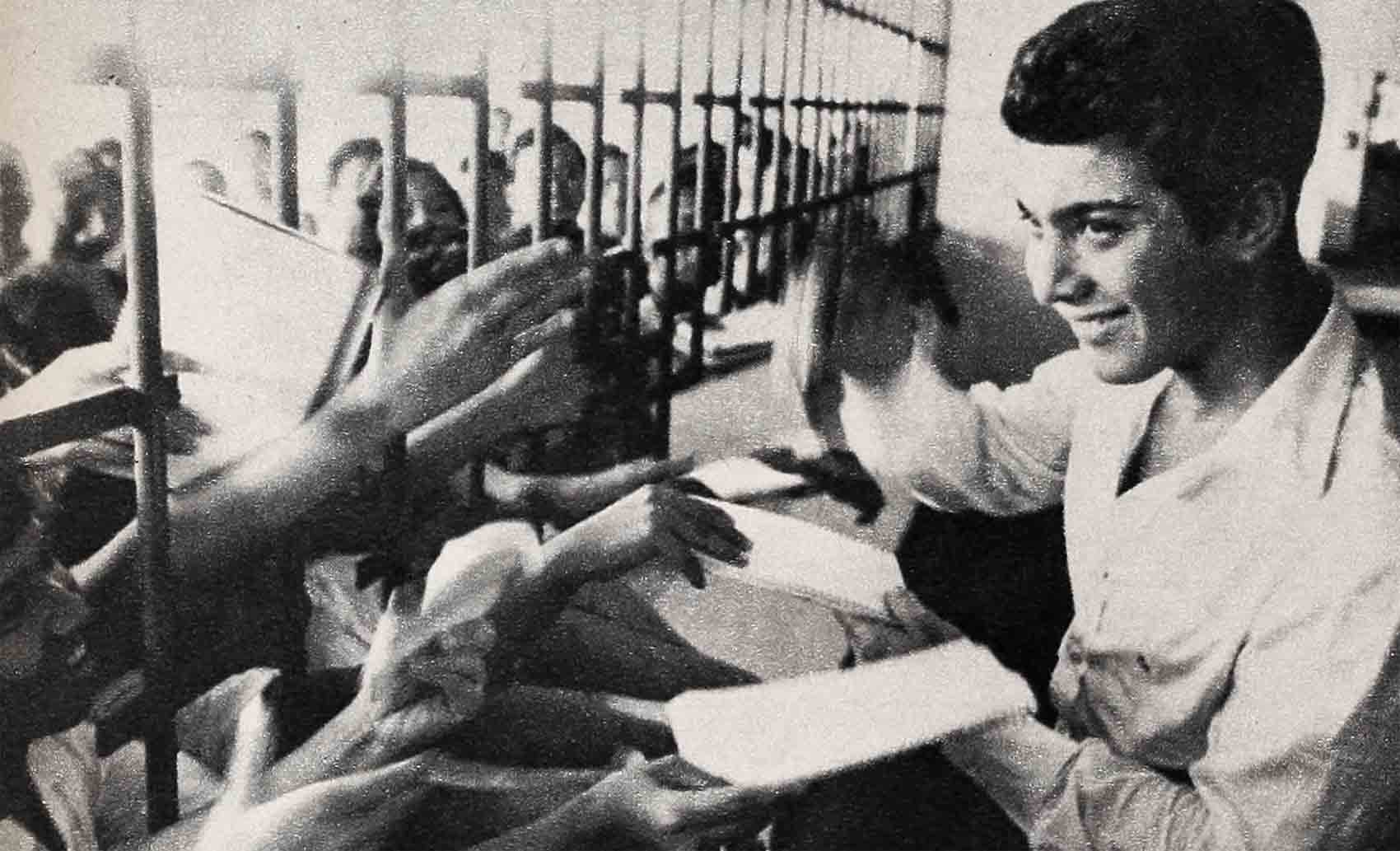

The party was crowded that afternoon when Paul Anka walked on stage of the night club which was “for rich.” About five hundred children from all over the Island had been invited—kids from orphanages, from homes for the crippled, from welfare institutions—and La Perla slum.

There were gifts for everyone—toys and candy and refreshment. The room was loud with the good sounds of laughter and happy shouts in Spanish and English.

Paul sang his first numbers and then got the kids singing Yi, Yi, Yi, as if they never wanted to stop. Then, as he slowed down his pace, his eyes roamed over the young audience. It wouldn’t be easy to find one tiny girl in that crowd. But she had found him, and that hadn’t been easy.

He sang a tricky song about his friends Tommy Sands, Bobby Darin, Frankie, Elvis, Ricky and Fabian. As he sang he looked all around the club—here, there, in the back of the house, in the front—and then there she was. Wearing the same faded red dress that looked like it was made for someone else. Staring up shyly at him and smiling a little. Paul cocked his head and leaned to get a look at her feet. She blushed as she slowly moved her feet out into the aisle. She was wearing bright new shoes.

They looked at each other and smiled a secret smile, because they shared a secret. The secret of what this concert meant. There was an understanding between these two, the young man whose time for children of his own would have to wait. And the little child who had waited so patiently to hear him sing.

THE END

—BY ANNE DAWES

See Paul in 20th’s “The Longest Day.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1962

No Comments