We Grant Marilyn’s Last Wish

“I want the world to see my body. That was Marilyn Monroe’s law wish, expressed directly in words, few months before she died, to the photographer who took revealing shots of her on the set of her never to-be-finished film, “Something Got To Give.”

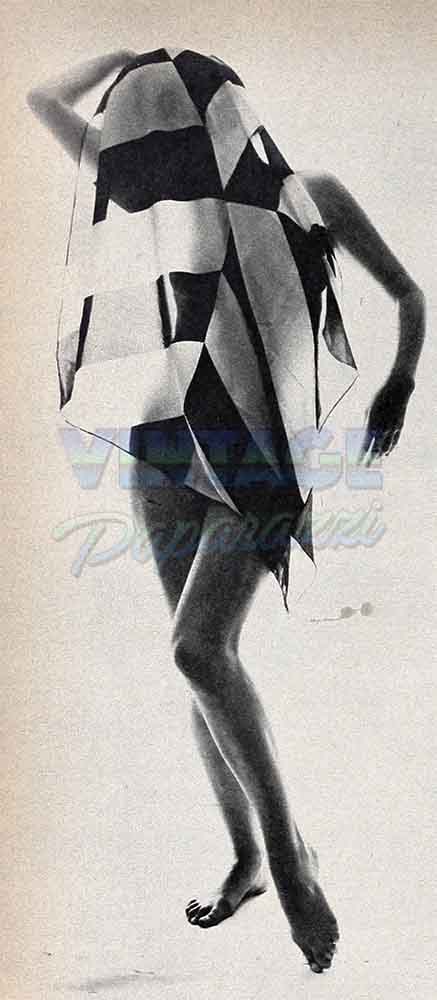

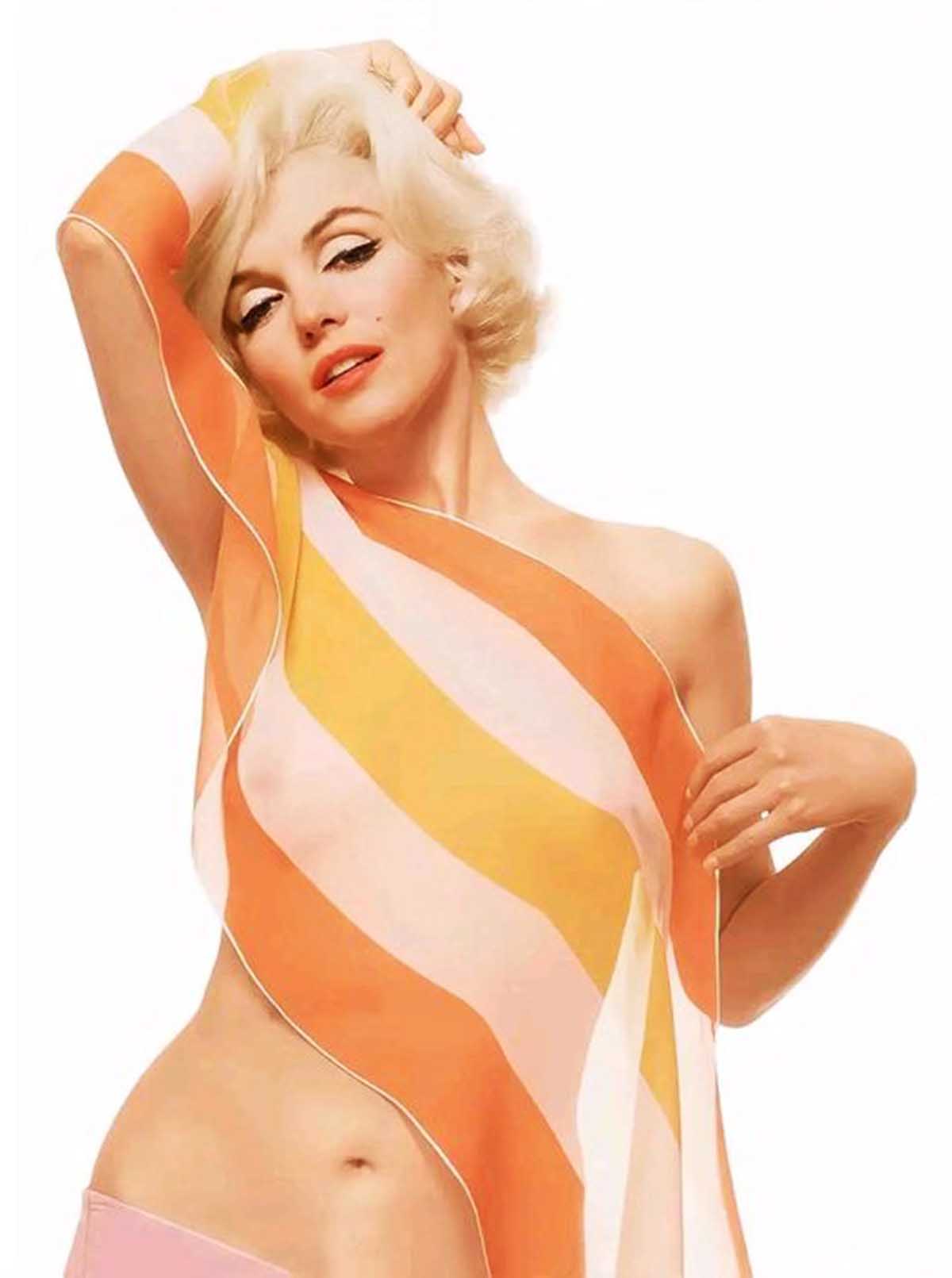

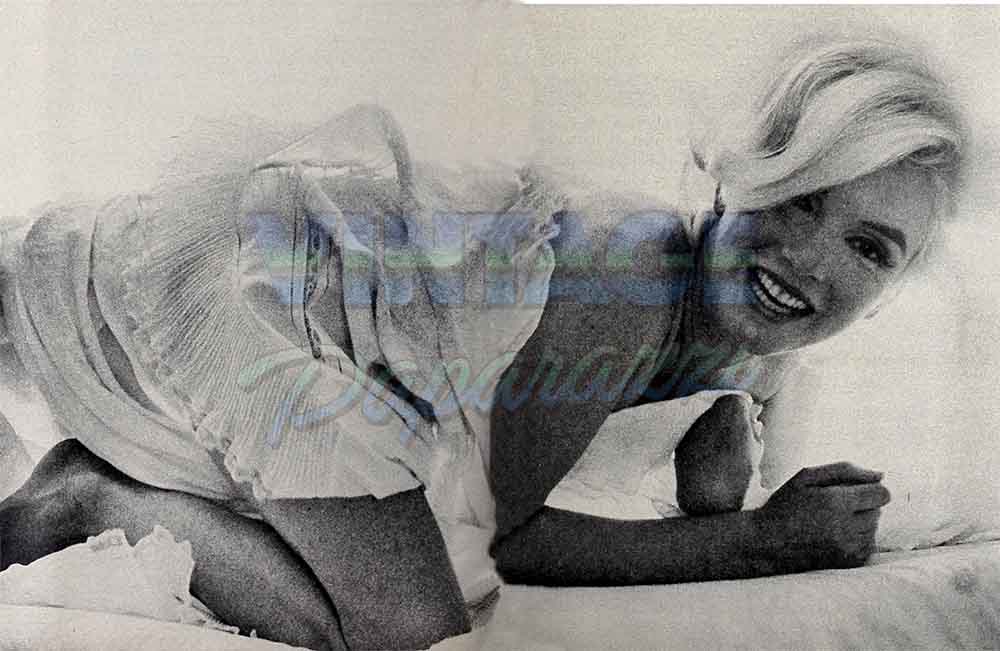

“I want the world to see my body.” That was Marilyn Monroe last will and testament to her fans expressed directly, through her actions, to another photographer, the famous cameraman Bert Stern when, during the last sitting she ever posed for—a fashion layout for a special section in Vogue magazine—she suddenly left the room and returned wearing nothing but a transparent top above and black-and-white striped towel below. The effect was electric.

“Not bad for a girl of thirty-six eh?” Marilyn asked, posing saucily.

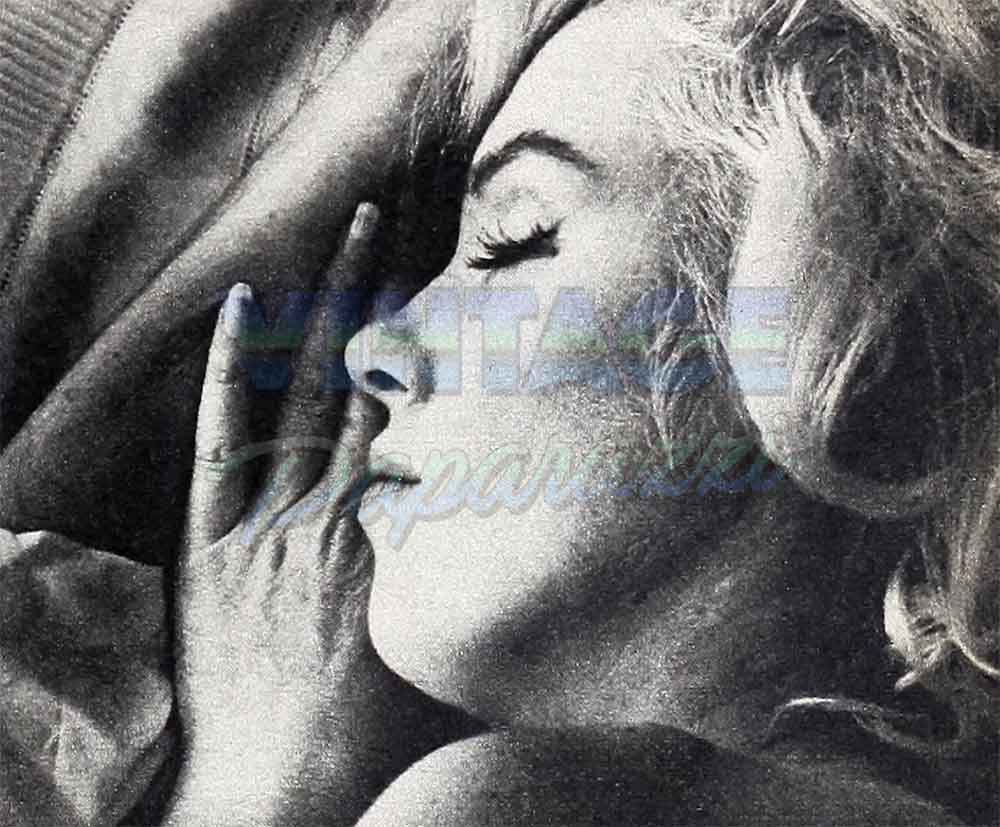

Not bad, indeed. “She was thirty six but she looked twenty-two,” recalls photographer Stern. “Very beautiful, more so than I’d ever imagined. She was so exciting, so creative in front of a camera. She loved working with her body, was an expert in using her body in photographs; a perfect model.”

So she posed until late that night—in clothes, in the towel, in a diaphanous scarf, in the nude. “She was great—witty and delightful,’ Stern says. Marilyn, in turn, was truly delighted when she saw the negatives from the sitting. (You can see for yourself why this was so by looking closely at the prints of those negatives that we’ve reproduced for you on these pages of PHOTOPLAY—and on our cover.) “She posed because she wanted them printed; otherwise she wouldn’t have posed,” Stem says. “There was some question at Vogue about eliminating the whole section after Marilyn died. But we felt that this would be unfair to her. She posed in the way she did, when she did, because it was her wish to. And not printing those final pictures of Marilyn would be denying her wish.”

AUDIO BOOK

“I want the world to see my body.” This was Marilyn’s wish at the end of her life as it had been from the beginning, when she was plain Norma Jean (“The Human Bean,” as her playmates called her), a thin, gangling, rejected, scared child with a nervous stutter. “I used to dream,” she later wrote, “I was standing up in church without any clothes on. and all the people there were lying at my feet on the floor of the church and I walked naked with a sense of freedom over their prostrate forms, being careful not to step on anyone.”

A dream of nakedness, a dream of freedom. She was six when she first had this vision of escape and of power and. as she explained years later to writer Maurice Zolotow, “My impulses to appear naked had no shame or sense of sin in them. I think I wanted people to see me naked because I was ashamed of the clothes I wore. Naked, I was like other girls and not someone in an orphan’s uniform.”

To be pretty, to be admired and desired, to he like other girls, to be loved and not ashamed: this was Norma Jean’s dream. In life, as in her dream, it was to be her body—clothed, partly clothed and unclothed—that was to bring her closer to happiness and yet. at the same time, keep her further from fulfillment.

Her first sweater

When she was twelve—as she later recalled—“I was going to Emerson Junior High and one of the girls in my class made fun of a dress I was wearing. I don’t know why kids do things like that, it really hurts. Well, I ran home crying.” But the next day she was back at school in a borrowed white sweater (a size too small for her) and with make-up on her face for the first time. “My arrival in school, with painted lips and darkened brows, in the white sweater, started everybody buzzing. When I walked into the room, the boys started moaning and groaning and throwing themselves on the floor.”

The lure of her body got her lots of dates (“The boys knew better than get fresh with me. The most they ever got was a good-night kiss”), and a husband when she was sixteen. Right after her wedding, she and the groom went to a night club to celebrate. When she returned to their table after joining other patrons and the entertainers in a hip-swinging conga line, her husband. Jim Dougherty, snapped, “You made a monkey out of yourself.” Four years later they divorced. Dougherty, recalling the period she spent with him when he was a physical education instructor at the Catalina Island U.S. Merchant Marine base, says bitterly, “She knew she had a beautiful body, and she knew men liked it. She didn’t mind showing a little bit of it.”

Norma Jean got a job in a war plant. but even her drab work clothes weren’t able to hide the body beneath. “Putting a girl in overalls is like having her work in tights, particulary if a girl knows how to wear overalls,” she said.

Army photographer David Conover came to the plant to shoot morale-boosting shots of pretty defense-workers, which were to be distributed to GI newspapers, and happened upon Norma Jean. He took pictures of her. and the lab man who developed the prints said enthusiastically to Conover. “Who’s your model, for goodness sakes?” Army men all over the world. when they saw the finished photos in Yank, Stars and Stripes and camp newspapers, shouted. “Wow!”

So Norma Jean became a model, mainly for “girly” magazines; and her body (sometimes they printed her face, too) was featured on the cover of five such publications in one month alone in 1946. A Hollywood studio head, thumbing through a stack of such magazines, kept seeing her picture. That’s how Norma Jean was called for her first screen test.

As a starlet, during the years between 1946 and 1951. she made sure that she showed her body whenever and wherever she could. It was all she had, really. Her name, Marilyn Monroe, was not her own; her hair, died platinum despite her objections. was a color she despised; her face, changed and rearranged by every trick and device known to the beautician, belonged to Marilyn Monroe, not Norma Jean: her talent—well, as the studio people kept saying, it was “potential”; and her intelligence and sensitivity—the man she was in love with then, Freddy Karger (now married to Jane Wyman), told her, “Your mind isn’t developed. Compared to your body, it’s embryonic.”

If her body was all she really had, then she’d really use it. Not sexually to advance her career. Biographer Zolotow quotes one producer—and says he represents all the be-nice-to-me-and-I-can-help-you men who chased Marilyn during this period and never caught her—as saying. “Marilyn never slept with a man who could do her any good.” But she’d use it professionally to advance her career. To make it enticing, inviting, exciting, she exercised forty minutes at the start of each day. To develop her breasts and “keep them good and firm,” she’d end her exercise period by rotating dumbells extended above her head. She’d cleanse and perfume and pamper her body—even if that meant being late for a dinner date at eight o’clock.

“Eight o’clock will come and go and I will remain in the tub,” Marilyn once wrote. “I keep pouring perfumes into the water and letting the water run out and refilling the tub with fresh water. I forget about eight o’clock and my dinner date.

“Sometimes I know the truth of what I’m doing. It isn’t Marilyn Monroe in the tub but Norma Jean. I’m giving Norma Jean a treat.

“After I get out of the tub I spend a long time rubbing creams into my skin. I love to do this. Sometimes another hour will pass, happily. When I finally start putting my clothes on, I move as slowly as I can. . .”

“Cheese-cake” art to advance her career. “The yummiest ‘cheese-cake’ pictures I ever snapped,” said one photographer after a successful session with Marilyn.

Hip-swishing to advance her career. The Marx brothers were looking for a sexy blonde for a non-speaking part in one of their pictures. “Actually, it was just a walk-on, but the walking was important,” Marilyn said. “Groucho asked me if I could walk in a way to make smoke come out of his head. I told him I never had any complaints. I walked across the room and, when I turned around, there was smoke coming out of Groucho’s head.”

Trying to act sexy to advance her career. Arthur Hornblow, the producer of “The Asphalt Jungle,” recalls today how things went at Marilyn’s audition for the role of Angela in the film. “She was trussed up and laced up and badly got up,” he says. “You see, she had heard we were looking for someone very sexy, so she had dressed accordingly, overemphasizing her figure at every point . . . Hollywood at its very worst had produced this girl who came into our office, this absurdity, this little nervous girl who was scared half to death, who heard we wanted someone sexy, so she dressed as a cheap tart.

“And yet Huston (John Huston, the film’s director) and I liked her right away.”

The public loved her when they saw her in the picture. Her sexiness vibrated right out of the screen and electrified the audience. Miraculously, even the women responded to her, for Marilyn Monroe had the rare faculty, on and off the screen, of kidding her own luscious sexual magnetism at the very moment when she was turning it on.

Marilyn’s body had made her a star.

“I want the world to see my body.”

“Clash by Night” was in the can and set to be released, and she was just about to make “Don’t Bother to Knock” when news leaked out to the studio that a nude calendar for which she had posed years before (she’d been broke, was a week behind in the rent, and the money, fifty dollars, had seemed like a million), was about to be circulated, of all things!

She told the truth

The studio was upset and Marilyn was upset. The studio heads advised her to deny she’d posed for it. Marilyn, after Consulting with her friend Sidney Skolsky, decided to tell the truth, even though it might mean the end of her career.

But of course it didn’t. When the story broke in the papers (“Oh, the calendar’s hanging in garages all over town,” Marilyn was quoted. “Why deny it? Besides, I’m not ashamed of it. I’ve done nothing wrong.”), the public couldn’t wait to see her on the screen. As Zolotow puts it, “The nude calendar established Marilyn firmly as the epitome of the desirable woman of her time, and from then on, no matter how fully dressed she was on the screen, the audience could see, beneath the cinematic image, the naked Venus.”

Marilyn’s body brought her fame and fortune, but it did not bring her happiness. It attracted to her a second and a third huband, Joe DiMaggio and Arthur Miller, but the fact that they had to share her body with the movie-going public helped drive them away. The final frustration for Joe DiMaggio was probable when he stood in a crowd of 4,000 or lookers in front of the Trans-Lux Theatre on Lexington Avenue in New York watched the shooting of a scene for “Seven Year Itch,” in which an air blast from subway grating kept sending his wife’ skirts flying over her head. “I shall never forget the look of death on Joe’s face, director Billy Wilder says. The final indignity for Arthur Miller was probably when he escorted her to the London premier of his play, “A View from the Bridge.” His wife wore a bright red strapless evening gown that was more revealing than if she were nude and, in the words on the Associated Press, “Marilyn Monroe’ close-fitting dress turned the London opening of her husband’s latest play into near-riot.”

As time went on, especially after “Bus Stop.” the critics began to recognize than in addition to her obvious “flesh impact’ Marilyn possessed a rare, acting talent But Marilyn herself, in spite of all her stated intentions of wanting to be “great actress,” never believed it.

Voice vs body

Marilyn Monroe’s body was never love lier than it was that night at Madison Square Garden, early in 1962, when, encased in a flesh-colored Jean Louis gown she appeared at President Kennedy’s birthday tribute. But the sweet, scared little-girl’s voice that sang “Happy Birthday” was Norma Jean’s.

Marilyn Monroe’s body was never more enticing than it was that day at the studio, a few months later, when, refusing to wear a flesh-colored bikini (“I’d rather do it in the nude,” she said.), she splashed around naked in a swimming pool scene, revealing her calendar-girl, 37-22-35 figure. But the frightened, trembling mind that stayed away from the set of “Something’s Got to Give” on other days because “nobody wants me, nobody loves me, nobody cares”—was Norma Jean’s . . .

Marilyn Monroe’s body was nude when they discovered her, an apparent suicide from an overdose of drugs, in her bed at her Hollywood bungalow. The features of Norman Jean, lying face down, were pressed into and hidden by a sheet. Later, a studio makeup man, a studio hairdresser were to give both face and body the illusion of life, as they prepared the star for her farewell appearance, her funeral.

Her obituary. Perhaps some of Clifford Odets’ words in Show magazine are most appropriate. “It has often been said of Marilyn that she made vulgar display of her figure. Wouldn’t it be kinder to say that she hoped if you looked at her body you might not scrutinize her face too closely? Her face that was not quite as grown up as she wanted it to be? Many another, much less insecure, goes visiting with a small gift in hand when he is not sure he will be welcome at a friend’s door. Perhaps Marilyn’s lovely shape was the little gift she brought, hoping that it would please you if nothing else about her did.”

Her lifelong dream, her final wish, her last will and testament, her enduring legacy: “I want the world to see my body.”

—JIM HOFFMAN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1963

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments