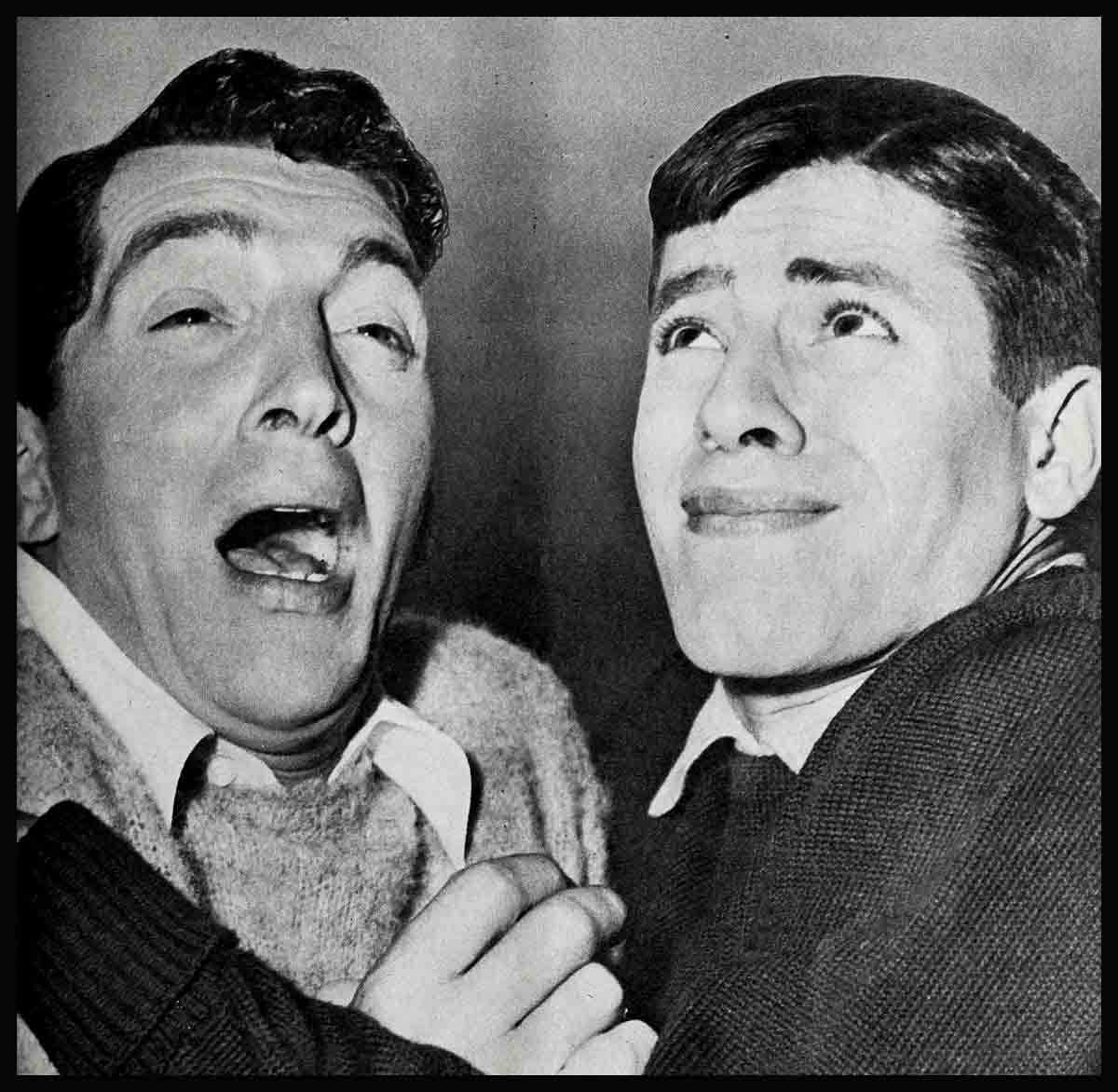

Behind The Riot Act—Dean Martin & Jerry Lewis

Dean’s the one with the eyes that laugh. Jerry’s eyes are sad as a flop-eared hound’s. Dean’s the casual type. If the house took fire, he’d say, “When it hits my bedroom, wake me up.” Jerry’s a rabid perfectionist. Let him find the papers on his desk disarranged, and it kills his day. Dean takes life as it comes. Jerry meets it head-on, always braced for the worst. Dean’s consistently buoyant. Jerry’s intense, mercurial, the traditional clown crying on the inside. His contract allows time out for nervous breakdowns.

Dean’s of Italian stock and lets everyone know it. Jerry’s equally proud of his Jewish heritage. If Dean likes you, he calls you mustang. If Jerry tells you you’re cra-a-zy, that means you’re in. He’s the business end of the combo, though they worked out their basic strategy together. “We’ll try it nice three times. If they still push us around, then we’ll start screaming.” Screaming and other details are handled by Jerry. “I worry anyway. Why should we both worry? Let. Dean play golf. If he’s happy, I’m happy.” Golf is Dean’s notion of paradise.

Jerry likes golf but without the same concentration. His passion is show business. He has a genius for order, and spends blissful hours with his Patti over the fantastic record of the joint careers of Martin and Lewis. One hundred and eighty handsomely bound volumes hold every clipping, the photographed story of every tour, a transcript of every radio show. Every TV program is kinescoped, every movie transferred to 16mm film, every item catalogued to a fare-thee-well. It’s a labor that only love could contemplate. “I’m more egotistical about this,” he says, “than anything else. If we bellycrashed tomorrow, I could live it all over again in the books.”

He was born to the profession. Dean stumbled into it. Temperamental opposites, they fit each other like the hand in a glove. When either of them says “my partner,” it’s an endearment. Only fate could have brought them together. Dean’s pop was a barber, Jerry’s a vaudevillian. In Steubenville, Ohio, the Crocettis named their second son Dino. Nine years later Joey Levitch gave out with his first squawk in Newark, New Jersey. The kids grew into their teens with one thing in common: they hated school.

“l’m not going to be any doctor or lawyer or stuff,” Dino said at fourteen. “I want to quit school.”

“If you don’t go to school,” said Pop mildly, “you go to work.”

“Of course,” agreed Dino.

That’s all there was to it. His folks never made a big thing out of nothing. They were gentle people, and as parents they held a simple philosophy. “We have two good boys. Whatever they want is okay with us.” In this atmosphere of sunny approval, Dino and his brother Bill throve, free to develop their own personalities, freely returning love for love.

From his first job in a gas station, Dino leaped lightly to boxing, where he won (or lost) wrist watches and all the money thrown into the ring. Pop took this in stride. Mom didn’t care for it at all. Characteristically, she voiced no protests, but Dino came to dread the hurt in her eyes at sight of his mashed-up face. The mitts were exchanged for the steel mills. Finding in steel neither zest nor charm, he lent a lukewarm ear to Pop’s suggestion of barber college. “Here’s five dollars to enroll,” said his father. Thus armed, Dino got as far as the poolroom. He did, however, bring the five dollars back. Pop shrugged. “So the boy doesn’t want to be a barber, so he’ll be something else.”

He became a wheel dealer. A certain cigar store did a brisk trade in tobacco and a brisker trade at the gaming tables behind, where some of Dino’s pals were gainfully employed. After six months as a clerk out front, he made the grade to the rear—and again faced the hurt in his mother’s eyes. “A gambler?” she faltered. He took her hands. “Mom, you remember the picture about Monte Carlo?”

“I remember.”

“And the man with the stick? He didn’t gamble. Just worked.”

“You’re the man with the stick?”

“That’s right, Mom.”

Her face cleared. “Well then, it’s fine, Dino.”

It was fine all round. He wore sharp clothes. He helped Pop pay off the house and send Bill through college. His co-workers were kids he’d grown up with, bound to each other in wordless loyalty.

Joey was always being thrown out of school. Actually, school didn’t exist for Joey who lived in a magic world of his own. Dad had opened the door without foreseeing the consequences. Dad was Danny Lewis, comedy singer. Mom played the piano for him. Summers they worked at resort hotels and took Joey along. Winters they went on the road and left him in Newark with his grandmother and aunt. A boy needs regular hours, a boy needs schooling.

He was four the summer his folks played the President Hotel in Swan Lake. The curtains had to be drawn in order to strike a set, and Dad put Joey out front. He sang “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” The house applauded and his goose was cooked. The delicious fever entered his veins for good. Dad frowned on this. The trail had been rough for him; let Joey keep off it. Anyway, school came first. Mom stuck up for him, but Mom was away a good part of the time. The rest of the family called him a wild crazy kid and waxed highly vocal on the dark end in store for him. Which depressed him and sapped his sense of personal security, but stiffened his will. Some day, he vowed fiercely, he’d show them all.

Grams alone understood. “He’s a good boy,” she’d tell the others serenely. “I don’t worry about him.” And to Joey she’d say: “Whatever you want in the world, you can have it. Let your heart show you the way.” Hers was the golden rule, though she phrased it differently. “In life, the most important thing is to put yourself in the next one’s place.” It’s a rule he tries to follow and, for any success, gives | all the credit to Grams whose spirit molded him and lives with him today. He was ten when she died, and her death left him racked and desolate in a sunless world.

His next ally was Jimmy Gerard who worked with Dad, and saw in the son what “He’s a born professional. With or without your consent, he’s bound to break in. Why make it harder on both of you?” In the end Dad agreed, on condition that Joey confine himself to summer capers till he finished high school. Carefully crossing his fingers, Joey said, “Sure.” And a year later, being not quite fifteen, he applied as entertainer to a borscht circuit hotel. They looked him over. “We’ll take you on as waiter and athletic director (he weighed 102). And to make you happy, we’ll let you perform a couple of nights a week.”

If they made him happy, he did as much for them. Eyes, ears and comedy sense alert, he noted the oddities of customers, incorporated them into his act and raised such howls of glee that within two weeks he was outshining the importations from New York. A bellhop named Irving Kaye, with managerial leanings, caught fire and phoned Danny Lewis. “Look, your kid’s great. He could be pulling real dough. Get him out of here.” Dad was saved the trouble. Kaye turned from the phone to meet the cold eye of the boss. “You can go now,” he said. “And you can take the kid with you.”

Joey promptly made Kaye his manager, changed his name to Jerry and worked up what’s known in the trade as a dumb act. His hair in a mop, with waves yet, he pantomimed to records, topping things off with an operatic burlesque. An agent caught him in Newark and took him to Toronto at $225 a week. Unable to buck that figure, Dad threw in the towel. Jerry beat the legal age for ditching school by one year. Kaye continued as manager, switching later to road manager for Martin and Lewis. He’s still on Jerry’s payroll.

Till 1946 Jerry stuck with his record act, earning as high as $650, though not consistently. A measure of fulfilment brought him a measure of happiness. Deep down he remained restless, forever un-satisfied, forever trying to prove himself, forever questing for worlds to conquer.

Back in Steubenville, when the gang wound up at Walker’s Café, Dino was always asked to sing. From the age of six, when he’d sit on the curb and warble Italian tunes, he’d loved to sing. But for pleasure only. The boys knocked themselves out, making fun of professionals. They used makeup, didn’t they? So they had to be sissies, what else? All except Crosby. They listened respectfully to Crosby, who was Dino’s idol. Dino sat through Crosby’s pictures six times. Just for laughs, Dino tried to croon like Crosby. Crosby was in a class by himself. He could do no wrong.

Having performed at Walker’s one night, Dino sauntered back to his buddies. The guest band was Ernie McKay’s from Columbus. McKay came over. “Would you like to sing with the band?”

“Of course not,” laughed Dino, and wondered idly why Jiggs Rizzo got up to follow McKay and what they were sticking their heads together about. Jiggs soon enlightened him. “The guy’s got a good outfit. I told him you’d sing with him.”

“I will not,” said Dino, and this time he wasn’t laughing. Next day he walked in to work and said hello. Nobody answered. Dino became a ghost, a body unseen and a voice unheard. Three days was all he could take. Then he tackled Jiggs. “What goes on here?”

“We don’t talk to you till you sing with Ernie McKay.”

“I will not!” Again they closed ranks in a wall of freezing silence. Six to one, they broke Dino down and drove him forth to Columbus. Within a month he was back.

“I quit. You sit there and people look at you. Makes me feel like a dope. You get up and sing a fast second chorus and sit down again. This is to me monotonous. I’m used to dealing chips.” He scanned the circle of faces, unmoved by his plaintive plea, and exploded bitterly. “Who said singers are sissies?”

“We made a mistake. You gotta voice. You gotta chance to better yourself. You gotta take it.”

“I can’t take it. I’m used to good dough. I can’t live on sixty a week.”

Jiggs turned to the others who gave some imperceptible sign of assent. “We’ll make up the difference.”

Defeated as much by their inflexible purpose as their generosity, Dino bade his sponsors adieu and made his doleful way back to Columbus. Till his salary rose to exceed his former earnings, the boys faithfully kept their pledge. The turning point came when Sammy Watkins heard him over the air and made him an offer. This impressed even Dino. He eyed his potential career with dawning respect.

He stayed with Sammy two years. He married Betty MacDonald. He played gin between shows with Merle Jacobs of MCA. One night Jacobs said: “Are you ready?”

“Sure. Where are the cards?”

“Cards, shmards. Are you ready to go out solo?”

“With what? I have no arrangements.”

“We’ll get you arrangements. You’re following Sinatra at the Riobamba in New York.”

“Oh no!”

“Oh yes.”

A week later he stood in the wings of the Riobamba, waiting to be introduced as the new sensation. All he heard was the introduction to his first song. Sitting ringside were dazzlers like Sinatra, Como and Haymes. He felt real shaken till he saw people turning, asking each other his name. This appealed to his humor. “I’m Dean Martin,” he laughed. They applauded the laughter, the name, the song and the singer. They called and recalled him till he could sing no more. The Riobamba held him for ten weeks.

It was Sammy Watkins who changed his name to Dean Martin. At the time it seemed normal procedure. Everyone changed names. Now he rues the day and yearns to be Crocetti again—because of his folks and because it’s Italian. Last winter he compensated by naming his youngest son Dino.

Jerry was playing the Downtown Theatre in Detroit. He was all of eighteen. He dressed like a character out of Damon Runyon. With girls he fancied himself a heller, his approach being grab-me-babe-before-I-disappear. This was the front behind which a lonely youngster’s eyes peered out.

He was sitting on a table backstage when she walked in, a trim little package of brunette loveliness. Even at eighteen, a picture of the girl he hoped to marry had long been enshrined in his heart. This girl looked just like her. “Hi! You’re having dinner with me tonight.”

“Are you for real?” she inquired coldly (which is where he got the expression) and kept on walking. To be slapped down was a novel experience. He liked it. Within two days he was crazy in love.

She was Patti Palmer, singing with Tommy Dorsey’s band because she needed the money. She didn’t care for the life, she didn’t want a career. Her goal was a home, husband and kids. Between numbers, she sat in her dressing room knitting. Jerry knocked at the door and apologized for being fresh. He started a ceaseless bombardment of attentions and proposals, told her he was twenty-two, wrote love notes in lipstick on her mirror, acknowledged an introduction to her mother by stating, “I’m going to marry your daughter.” The mother laughed hysterically, and to Jerry it didn’t sound good. His next note read: “If you will please marry me, I will give you the following.” The following included 1 mink coat, 1 Cadillac, 1 diamond bracelet, 1 white house with a picket fence, and other assorted pies in the sky. Came the day when Patti said softly, “I love you, you crazy.”

In October 744, three months after their meeting, they were married in New York. Gary was born the following year.

Theirs is a continuing love story. Apart, they’re practically mental cases. If she’s not home when he gets there, the house is a shell. One by one, he’s checked off the items on that impossible list of eight years ago and given them to Patti. Her most cherished gift didn’t appear on the list. It’s a song that can’t be bought in the shops. Jerry outlined his idea to David and Livingstone, and they wrote it for him. He had it scored, engaged a string orchestra of twenty, recorded it and dropped eager- hearted hints. “It’s the only thing of its kind in existence. You’ll never guess it.” On their sixth anniversary, he handed her the platter, then played it for her. From the machine flowed a voice that wouldn’t cop medals but was burdened with love:

“One night two precious stars

Came falling from the skies,

And they became the eyes of Patti.

A sunbeam stole along

To shine for just a while,

Then turned into the smile of Patti.

And to complete this work of art,

Out of love and faith they made her heart.

And when the job was done,

I thank the Lord above

For giving me my lovely Patti.”

As the last note died away, she broke down and wept.

“We’re two of the cryingest people in the world,” explains Jerry. Adding with irrefutable logic: “That’s why we’re so happy.”

On a Broadway corner in 1942 a couple of citizens were exchanging the time of day. One spied a familiar figure. “Hi, Jerry!” The figure stopped. “Dean, this is Jerry Lewis. Jerry, Dean Martin.” Dean grinned at the skinny kid, his face so alive under the pompadour. The grin warmed Jerry. “Gee,” he thought, “I’d like to be friends with this guy.”

His wish was granted when fate booked them into The Glass Hat at the same time. His screwball humor captivated Martin. Or as Dean reasonably puts it, “The fellow was nuts. I liked him.” Following each other in and out of various clubs, they’d leave notes of cheer on the dressing room walls, which cemented their friendship.

. . . Skip to ’46 and the 500 Club in Atlantic City, where Jerry was doing his dumb act. Overhearing the boss say he needed a singer, Mr. Lewis jumped in with both feet. “I have a singer.”

He improvised recklessly, “Not only that, but we do funny bits together. In fact, we’re a riot.”

The boss considered. “You sure you’re funny together?”

“Till you’ve seen us,” said Jerry with simple modesty, “you don’t know what funny is.”

They had no funny bits. Jerry went on and did his record act. Dean went on and crooned. Jerry figured the boss would be so enchanted with Dean, he’d forget the buildup. The boss wasn’t. “Next show,” he said, “get funny or get out.”

Next show they got funny, but not according to plan. All night they stayed up in desperation, jotting stuff down. When the time came, they tossed it overboard as by joyous consent. Because suddenly the spark ignited, inspiring them to such feats of brilliant lunacy as are still the talk of the trade. Where the gags came from or how, they still can’t tell you. Jerry loused Dean’s act up, Dean loused up Jerry’s, they badgered the waiters, insulted the customers and committed mayhem on the food. Their impudence knew no bounds, their good will no limits.. From midnight to 6:00 A.M. they adlibbed the crowd into hysterics, and the crowd still refused to let them go. Dean finally called a halt by crossing the stage with his bags. “When you’re through,” he told Jerry, “pack up, because I’m leaving.”

Word-of-mouth news swept the town like a prairie blaze, and people fought to get into the place next night. Within two weeks the boys were mowing ’em down at Loew’s State, and from then on it was up in a dizzying montage. Roxy’s, the Capitol and Paramount in New York, with the populace gone wild. Salary—$3,000, $5,000, $10,000 a night, which was just the beginning. An unforgettable preem at the Copacabana. A nation-wide tour on a nation-wide tide of laughter, with proud box office records toppling to bite the dust. Slapsy Maxie’s in ’48. Producers fell over each other flourishing contracts. Hal Wallis came out on top.

Movies, radio, Comedy Hour on TV, the career story needs no re-telling here. All the adjectives have been used, but the heroes of the saga are still rubbing their eyes. A recent letter from the Vice-President, asking them to appear for President Truman because they’re his favorites, rocked them both on their heels. When Jerry gets excited, his stomach rears. Dean made a quick try at jolting him back to normal. “Let’s call the President up and have him come here. Why should we go there?”

“No jokes, Dino,’ moaned his glassy-eyed partner. “This is for real.”

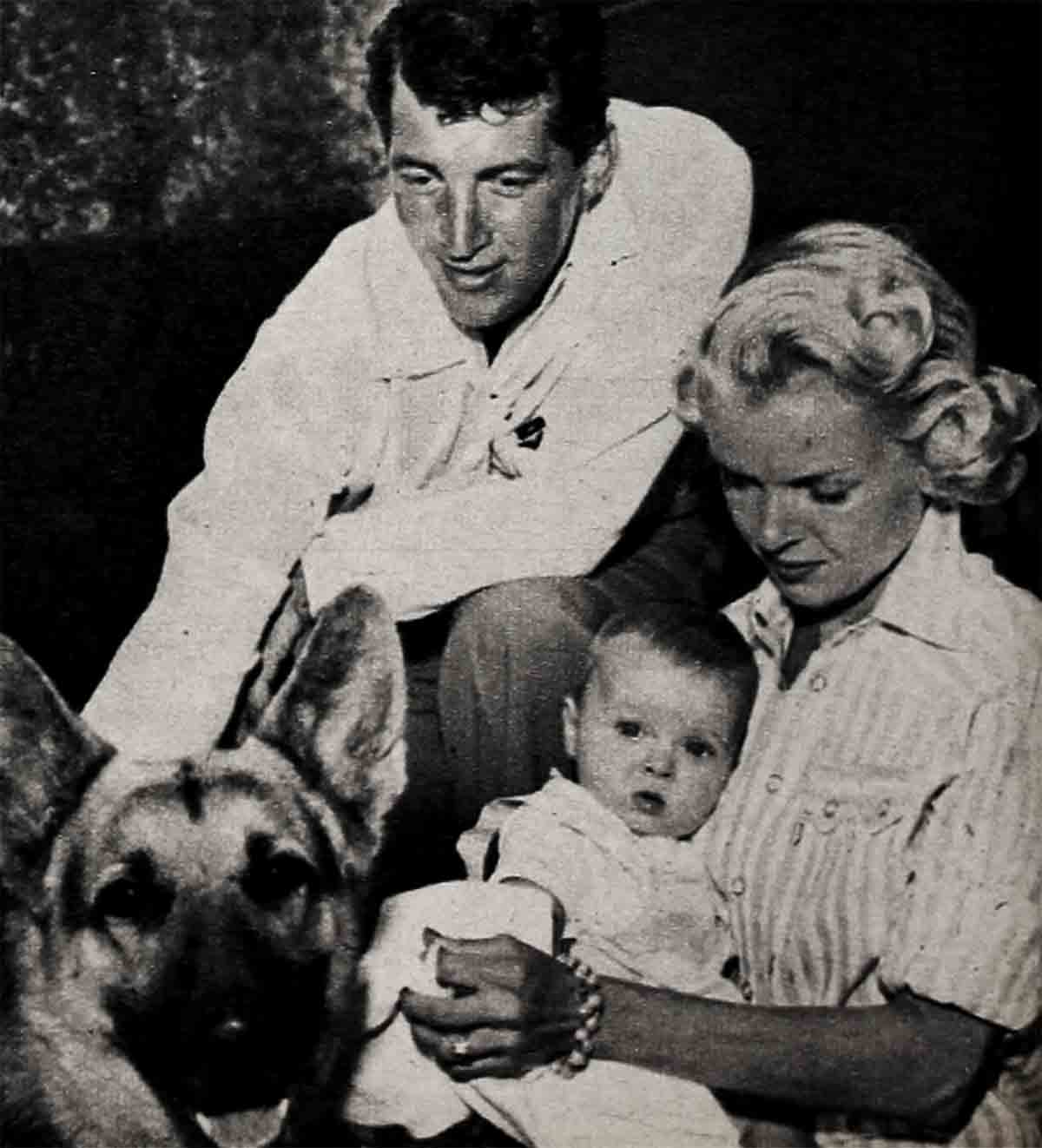

Deep-seated differences between Betty and Dean led to a divorce. He married blonde Jeanne Bieggers, pretty as a cover girl, which is what she used to be. The children of his first marriage live just round the corner. That’s why the Martins bought their present house—so the kids could run in at pleasure for breakfast, lunch or to spend the night.

Mom and Pop left Steubenville for the kindlier air of California before Dean ever got there. Sitting ringside, they witnessed his triumph at Slapsy Maxie’s. As in the old days, they didn’t say much. The quiet radiance of their faces said it for them.

Against his will, Pop’s retired from barbering.

“My pop,” declares Dean, “doesn’t believe I make money. He still pays on his barber’s license.”

“I believe, I believe,” says Pop.

He and Dean’s ten-year-old Craig are inseparable. When inactivity gets him down, he sticks Craig in the car for a Mexican jaunt. When that’s not feasible, he drives around looking for a Martin and Lewis picture that he’s already seen eight times. When he sighs for the feel of a blade in his hand, Mom consoles him with the reminder that he’s pleasing Dino. That does it. Their slogan is the same as Jerry’s. If Dino’s happy, they’re happy.

One day Patti and Jerry were driving in from the beach. A white house with a picket fence round it stopped them cold. Jerry found his voice first. “It’s like the good Lord dropped it down there just for us.”

A week after they bought it, he went on the road. Returning, he stepped into a place of gleaming wood and mellow colors, where nothing stuck out and everything belonged. Patti had done it all. She’d once heard him say, “In a house, I don’t like crystal, if you know what I mean.” She knew what he meant. She fixed him the kind of home that gathers you in and gives you peace.

Gary’s seven now. Ronnie, their adopted son, is two and a half. They plan to adopt more. “We want about five,” says Jerry. “Four at least. I figure we can afford to raise ‘em. And what does a guy work for, if not for kids?”

Obviously, money. But money’s not the essence. Cut him off from his work and he’d wither like a rootless plant. People like Chaplin have lauded Jerry as the greatest clown of the past twenty years, but his restless spirit remains unsatisfied and always will. Five years hence he wants to direct comedy, then to produce. For the immediate future Europe beckons. He and Dean have a date to keep at the Palladium. Then it’s Rome for Dean, and Israel for Jerry. “To see a couple of my Hebrew friends,” he explains. Actually, it’s to slake a burning curiosity for a sight of the land from which his people sprang.

The insecurity of his youth ate deep. In spite of love and friendship, wealth and fabulous success, he’s still uncertain. If he swatted a golf ball 240 yards, it wouldn’t mean a thing unless somebody said, “Nice drive!” Because throughout his impressionable years he was scoffed at, he needs to be told again and again that he’s good. Patti is always there to tell him. So is Dean.

The miracle of this partnership is that they’re as close personally as professionally. Closer, if possible. To both, the human equation is of prime importance, they share the same kind of warmheartedness and each worries more about the other than himself. Though a scant nine years divides them, it’s almost like a father-and-son relationship. Dean’s fiercely protective of Jerry. Jerry turns on Dean the eyes of a worshipful child. They’re forever exchanging tokens of affection. Something that cost sixty cents maybe, but always with a note that the other will get a bang out of.

One of their stage bits calls for Dean to catch Jerry. In Minneapolis on their last tour, Jerry missed a small movement, landed on his back with a sickening crunch and passed out. They rushed him to the hospital, with Dean beside him in the ambulance, racked by the dread that his boy’s back might be broken. The doctor couldn’t say till they’d made a series of tests and had taken some X-rays.

Meantime the audience waited. “What’ll I do?” asked the manager. “Refund their money?”

“I’ll go back,” said Dean. “At least I can sing a few songs.”

He stepped out to a tremendous ovation. Halfway through his song, emotion strangled him. He couldn’t choke out so much as a word of apology. He could only turn on his heel and get out of there fast. The manager apologized for him, while he fled back to the hospital and Jerry.

Not till dawn did the doctors bring reassurance. “It’s all right. The back isn’t broken. Just some badly torn ligaments which will heal.” Dean’s face started to crumple, but he controlled it. The tears that misted his vision he couldn’t control.

They call each other Dino and Jer. You could call them Damon and Pythias without going far wrong.

THE END

—BY IDA ZEITLIN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1952

vorbelutr ioperbir

4 Temmuz 2023I don’t even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was good. I don’t know who you are but certainly you are going to a famous blogger if you aren’t already 😉 Cheers!