The Saddest Love Story Of All-With A Happy Ending—Charlie Chaplin

She was young and her dark good looks had a beauty of another time. Her walk was proud and sure. There was a haunting quality about her face, and the light seemed to play tricks with her expressive eyes. She crossed Sunset Boulevard and waved gaily to a young girl who waved back and joined her. “Hello,” she said, and then, “Dad is feeling wonderful. He wrote me yesterday.”

She couldn’t be more than seventeen. She had a flawless complexion, and there was a sense of expressiveness about her, her hands, delicate and graceful as any duchess’, seemed to radiate a meaning all their own, as she told of her father. He was in Europe, she explained. Then the girl and her companion began to walk toward an outdoor restaurant, Cyrano’s. They sat down at a table on the terrace.

“And mother looks as beautiful as ever,” she said, smiling happily, “even though the kids keep her on the run all day.” There was more than just the girl to the family. There were seven brothers and sisters. She was the oldest and next came Michael, who was going on sixteen and who had the most Grecian nose she had ever seen. Except, of course, for her father, who was her image of a great man.

It had been eight long years of exile since that night in 1952 when her father had closed the mansion in Beverly Hills, and silently fled in the night to a strange land. It must have seemed all just a game to her to be whisked away to a new land. But in the haste of the flight, in the pinched faces of her gray-haired father and her fair-skinned mother, she must have sensed that it was a game adults did not enjoy.

In their new home, they never talked about that night. But later, when she was old enough to understand, the girl had read the story in a magazine. She read the terrible things they had said about her father. “An unsavory character,” the Attorney General of the United States had called him. . . . Some criticized him for never having become an American citizen. Others said his pictures were full of propaganda. “Disloyal,” they called him. Her father had denied the charges. And he had said, when it seemed he would never be allowed to return to America, “My children all were born Americans and I still would like to go back and live there.” At that time there were only four, the other three were born abroad. Her father had never returned to America.

“And now,” the girl said, “here I am, in Hollywood. I can’t believe it.” She nibbled at her tossed salad and her friend gulped down the oversized Coke a waiter put before her. They chattered on.

“Father loves when I play the piano for him,” she said, “and I love to hear his applause.” And she said, “It’s fun here, but I miss the family. We have so much fun. Momma never gets tired of laughing, although she must have seen father do the same funny trick a thousand times.”

She leaned across the table to whisper excitedly to her friend. “And this boy. . . .” And finally she said, “I’ll be going back soon.” Then her eyes clouded and, as if she didn’t want her friend to see, she lowered her head to pick an imaginary thread from her skirt.

Her trip had not been successful, and she tried to hide her disappointment. She had come so hopefully to Hollywood, but it seemed there was to be no future for her here. The doors she tried all seemed to be closed to her. Everyone remembered her father, of course, but, though they never said it aloud to her, she could see that most people had never forgiven him. People seemed surprised that she had come at all. Perhaps she had expected that. Perhaps that’s why she kept the trip just a quiet visit. Only a few people knew she was here. And then, before anyone knew it, she was gone.

There was to be no future for her in Hollywood. The answer to all her hopes had been “No.” Perhaps her father had expected that, too. It would explain why he had been against her coming.

Yet she was a beautiful girl. And talented. What was behind the doors that had closed to her, the sudden hardening of the face when people heard her name, the “no” she heard everywhere?

Another time, another girl

How long had it been since that other girl had come to Hollywood, the same age as this girl? Nearly twenty years. She was very young, too—barely seventeen—and very beautiful. She had jet black hair down to her shoulders and a full, generous mouth. She walked lightly on long slim legs, she didn’t smoke or drink, she dated only on weekends, and she had a delicious sense of humor. Her name was Oona—Oona O’Neill.

She too was the daughter of a famous man. Her father was Eugene O’Neill, the great tragic playwright. She had come to Hollywood against his wishes, looking for a career in the movies. Instead she met the great love of her life.

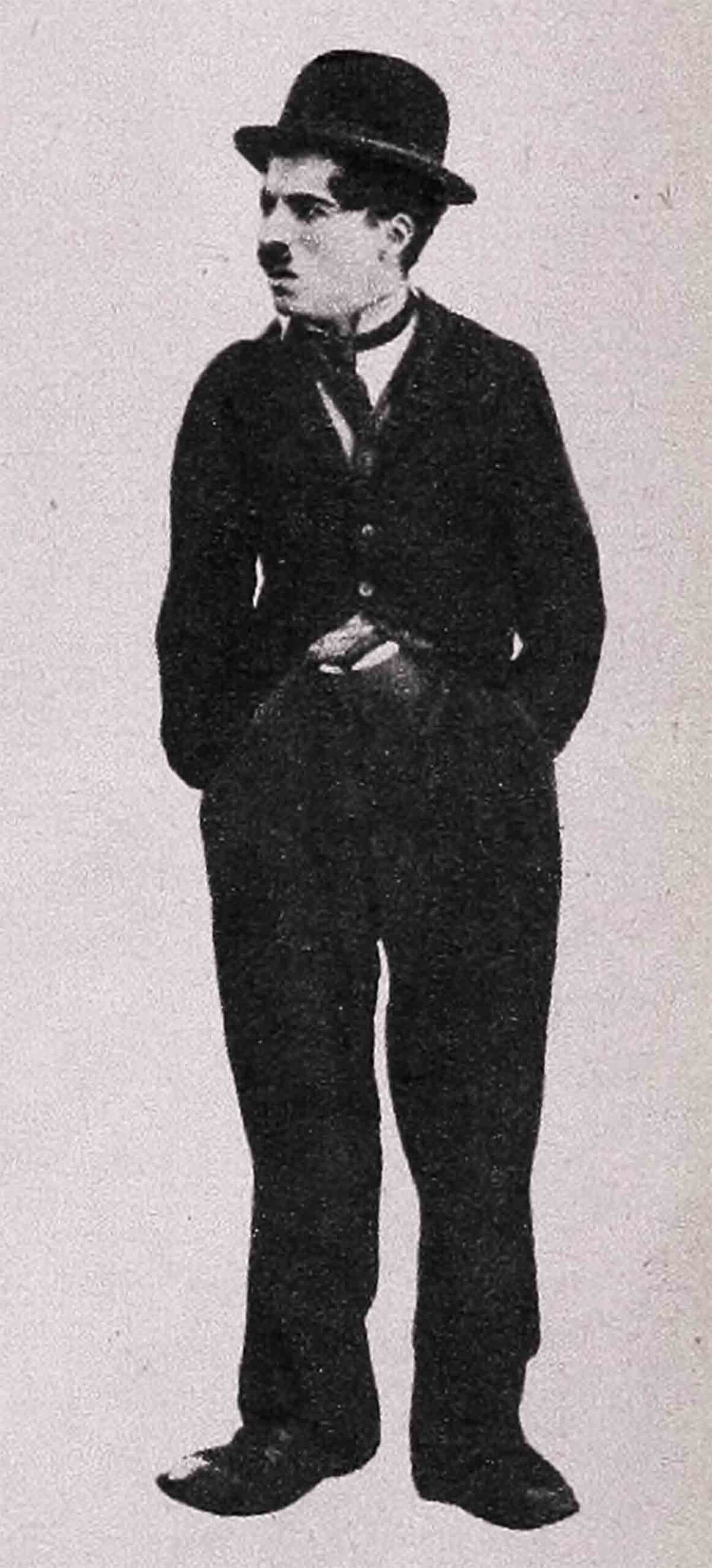

Oona had been going around Hollywood with Orson Welles. One evening he brought her to a luxurious house where the filmtown’s greats were in the habit of gathering for good food and talk. The host was a handsome, graying man of fifty-three—a charmer. The young girl was deeply impressed. So was he. Before the evening ended, Oona had forgotten Orson Welles, and Charles Spencer Chaplin was no longer interested in Joan Barry, a twenty-three-year-old girl who was then his protégée.

When Oona and Charlie fell in love. it caused a furor. Wherever they went, people stared at the stunning teenager and her elderly escort. They’d walk into a restaurant, she taller than he, and heads went together for whispers. “He’s three times her age.” Her father put his foot down against their unsuitable marriage and friends tearfully begged her not to commit such a tragedy. They told her everything she already knew—that he’d been married and divorced three times. That his first wife, Mildred Harris, had said, “A woman would have to be ten women to hold Charlie.” That even though his second teen-age wife, Lita Grey, had presented him with two sons, the marriage didn’t last. Neither did his third, to Paulette Goddard. And he was Hollywood’s Great Lover, she wasn’t the first young girl he’d been involved with.

Oona wouldn’t listen. “I love him,” she insisted. They made their plans to marry. And that was when Joan Barry shocked the whole country by suing Charlie for support of the baby she swore was his. He told Oona, “We’d better put off our marriage until I’m cleared, I can’t drag you into the mud she’s throwing at me.” Oona said stubbornly, “When you love a man, you want to be at his side when he’s in trouble.” She insisted on pushing the marriage date ahead to stand by him.

They eloped to Santa Barbara and were married on June 16, 1943. Later a blood test proved that Charlie couldn’t possibly have been this baby’s father, but the jury’s verdict was in Joan’s favor anyway.

But Oona didn’t question his love for her, and hers for him. She said, “He is my world.” She gave up all thoughts of a movie career, because Charlie felt that one star in a family was enough, and he was the star. Her role was that of a loving wife and soon mother of a stepping stone succession of children: Geraldine, Michael, Josephine, Victoria. . . .

And then, suddenly, she had to take her children and follow Charlie into exile. In England, she gave up her American citizenship and her children’s, and became a British subject “like my husband.”

When her famous father died a year later, she did not cross the ocean again for the funeral. Evidently the rift between them over her marriage had never mended, for she was not even mentioned in the will.

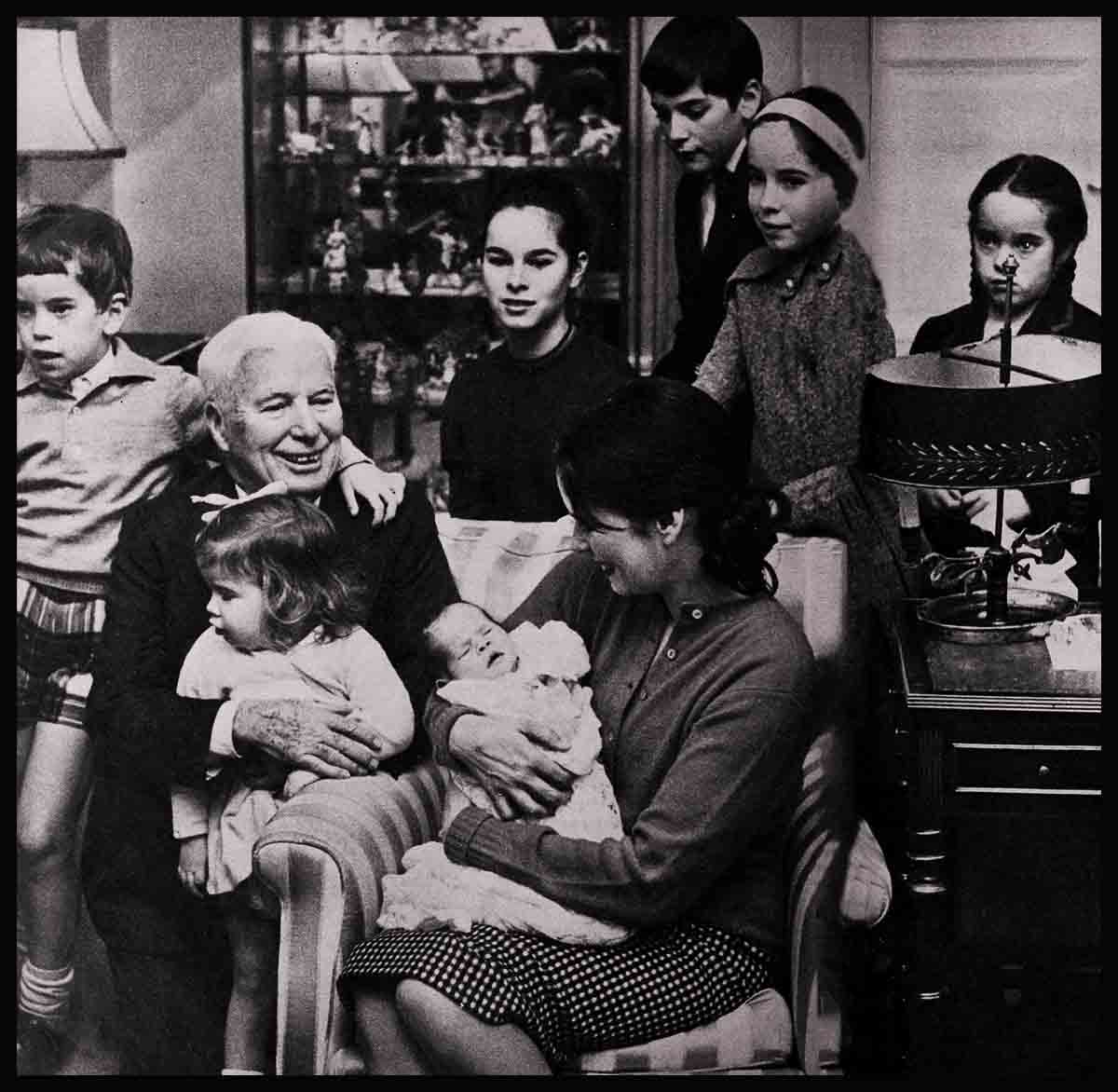

The Chaplins settled in an isolated mansion in Vevey, Switzerland, to live a secluded life. And everybody who had known the gay young girl mourned for her. “What an existence,” they said, “cut off from her world with an old, old man and nothing in life but to bear him babies every few years.” Tadpole was born in Switzerland (and touchingly named Eugene—for her father?); then Jane, and then Annette. Oona was seldom seen in the social world, and her friends sighed, “Poor Oona—poor lost girl.”

The saddest love story

If this was a love story, they said, it was the saddest one they’d ever heard. But what they didn’t know—because they didn’t hear from Oona herself, and she gave no interviews—was what life was really like in the Manoir du Ban, their palatial Swiss home.

The seventeen-room $350,000 mansion stands hidden in ten acres of beautifully kept park overlooking the blue waters of Lake Geneva. The days go by evenly and uneventfully. Everything is for the comfort of “Monsieur Charlot,” the master, but Oona is the one at the controls. She is a patient wife. She is the one who shields him from annoyances. calms him when he gets temperamental, and on the cook’s day off, she makes his favorite gourmet dishes. . . . She makes sure all seven children never, never disturb their father when he’s concentrating. For Charlie, it seems a contented sort of life, but her friends might wonder what happiness Oona, still young, could possibly get out of it.

“In our family,” says Oona, “the slogan is, ‘The more the merrier.’ I’m delighted with every new baby. Charlie tells everybody I look my prettiest when I’m expecting one. He’s crazy about the kids.”

The children are loved and wanted, but Oona makes it clear that the household doesn’t revolve around them—or her—only around Charlie.

Oona says, “Laughter is one of his great gifts to me—I never knew it as a child, I didn’t have a happy childhood.” But she also admits, “I’m probably the only member of the family who considers him as funny as he is. The kids are too intent on trying to be funny themselves.”

A shock to her

Oona is a woman with an amazing knowledge of how to be a wife. She is 35 now, to her husband’s 71, but to her he is ageless. “Only his birthday is the annual shock to me,” she says, “when the whole world seems to pour into our home with wishes. cables and presents.” Her figure is still so girlish that her oldest daughter borrows her clothes, yet Oona is glad of her first gray hairs. It has always annoyed her to be called Charlie’s “schoolgirl wife.” She and Charlie are warm host and hostess in their own home, but when it comes to going out, she is anti-social. Whatever her friends might have suspected about Charlie’s keeping her hidden from the gay, outside world, they were wrong. It seems instead, that it is he who has to coax her out.

“I feel our happiness depends on our being left alone,” says Oona. “In privacy he flirts with me as though we had just met. We are completely relaxed in each other’s company, we do not ask too much of one another.” She understands his crotchets and does not consider them signs of age—only of Charlie. “He is such a contradiction,” she ‘says, her dark eyes smiling, “When we do go out, I have to carry a large supply of change to do the tipping. Then he’ll go off and buy me an expensive car.” And she says, “He can make me feel like crying with rage when he won’t be nice to someone he should be civil to.” But instead of flaring up, she will squeeze his hand or kiss him swiftly on the forehead and he comes to heel—tamed. He is famous for his terrible temper, but she is one wife who can claim that “not once in all the years of our marriage has he lost it at me.”

“I have learned to keep silent,” she says, “and let him charge ahead. Unless he asks me for a criticism I never venture one. He respects my judgment, and jokes that I’m always right in the long run—because I try not to get on his nerves.”

This is Oona O’Neill Chaplin who protects, loves. honors and appreciates her husband. For all her good manners, she can be rude to anyone who upsets him. “Other young women,” she says, “who have married older men will understand what I mean when I say our marriage is founded on a rock.” Solid, with no unpleasant surprises ahead. The man’s character is formed, his life shaped, he has a sense of responsibility and tolerance. “We met when I was a mere child, and I have been in love with him ever since.”

This is the story not known to those who speak of Oona’s marriage as “May and December,” and mourn her lifelong exile. They don’t know that, for her, her story has had a happy ending.

But the Chaplins know it. “My father didn’t want me to come,” the lovely young girl had told her friend. She was the Chaplins’ oldest daughter Geraldine, and she’d come to Hollywood. Just as her mother did nearly twenty years before. When, it seemed, Hollywood didn’t want Geraldine, her father welcomed her home with open arms. Perhaps he didn’t want her to be a movie star or, as she thought a while later, a ballerina. Perhaps what he wanted from life for his daughter was what her mother had had—a love story with a happy ending.

THE END

—BY CHUCK ROSEN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1961

zoritoler imol

1 Ağustos 2023You are a very intelligent individual!