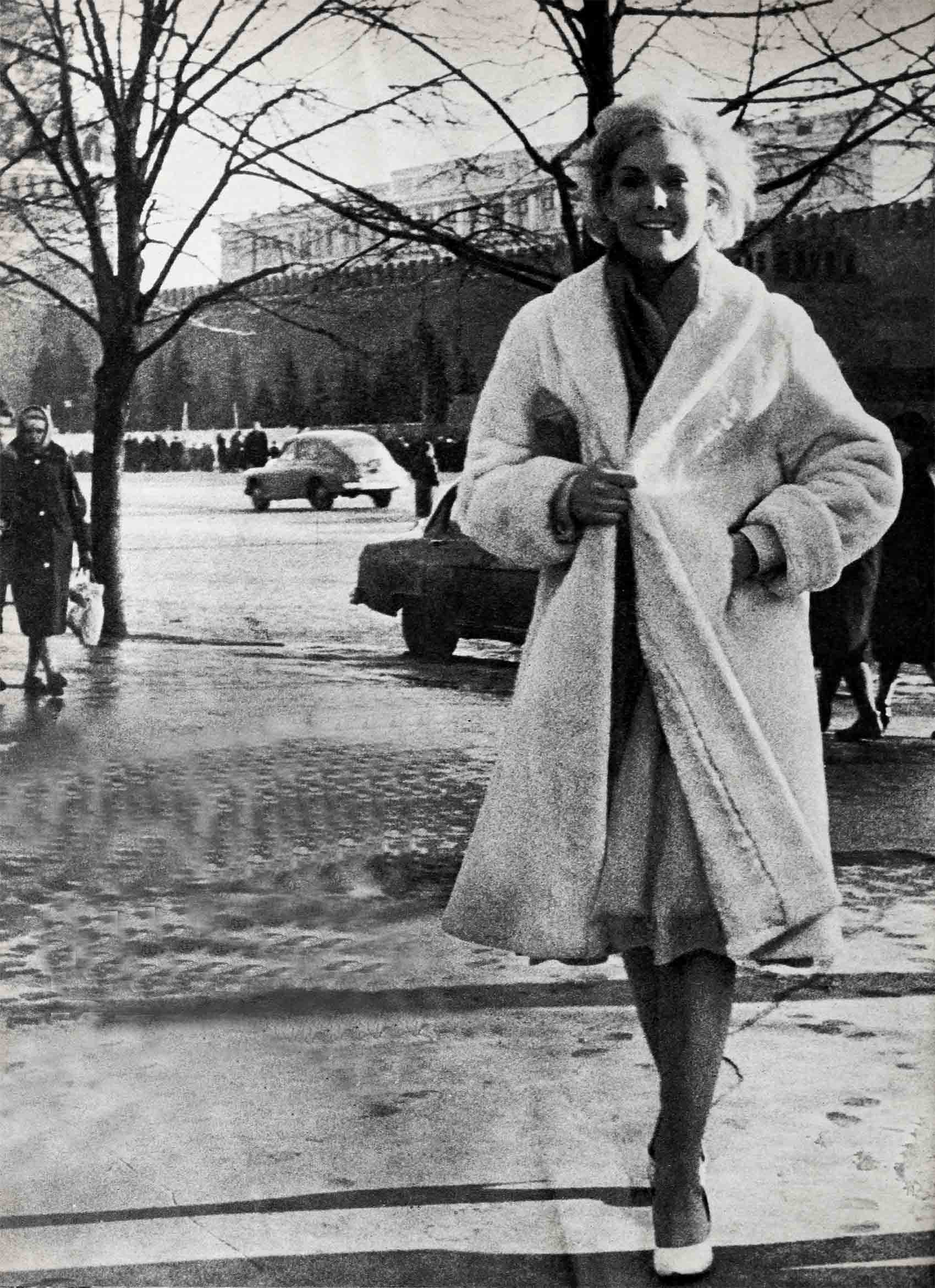

Kim Novak In The Kremlin

Don’t miss this exclusive report on Diplomat Novak—and how she carried on with the commissars on her recent trip to Russia. You’ll blush when you read what happened when a lavender curtain got tangled with an iron one.

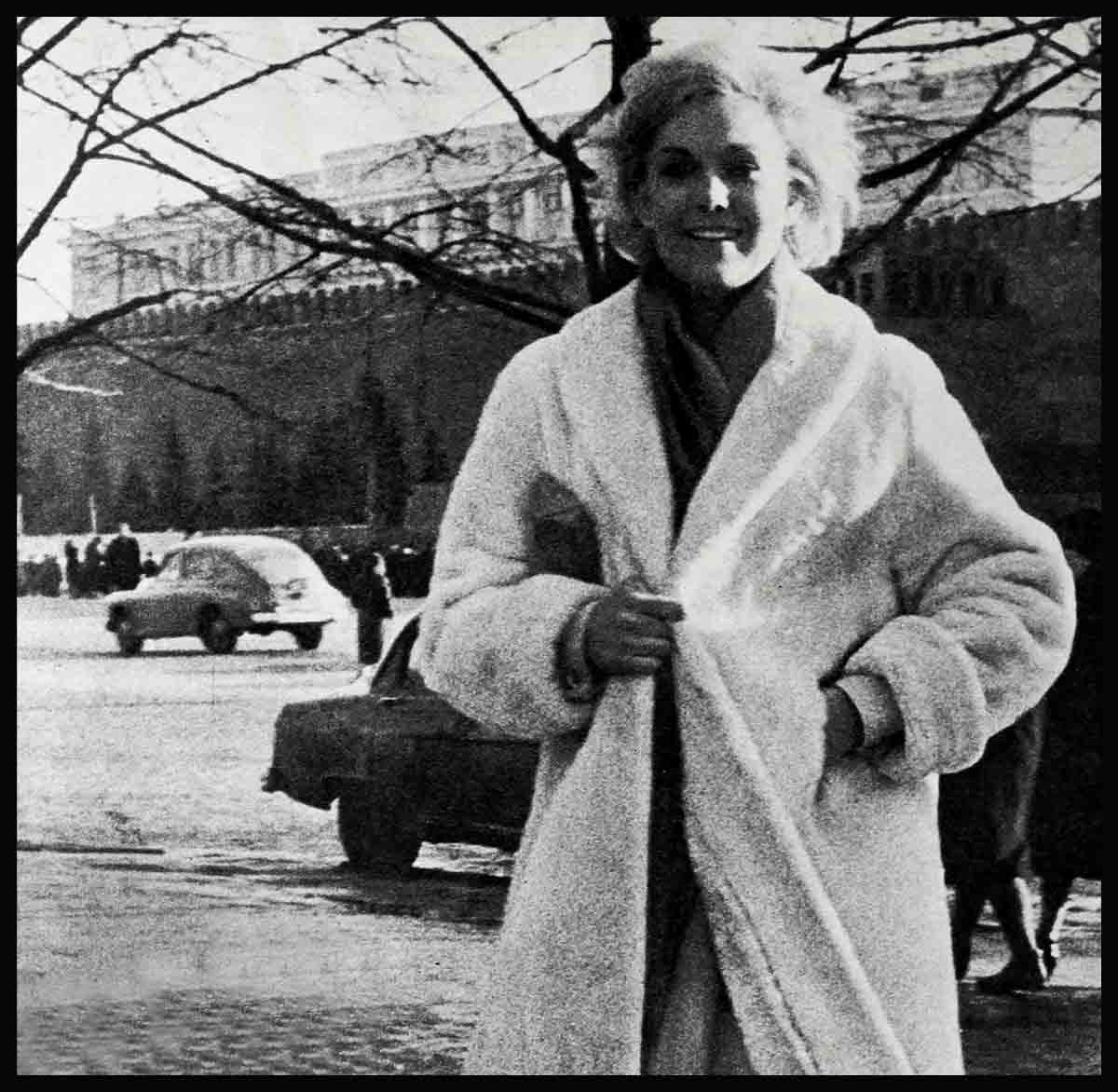

“It was freezing cold when my secretary, Barbara Mellon, and I stepped from the plane in Moscow into a foot of snow that soaked our nylons,” Kim Novak related. “I expected a reception committee, but no one was at the airport to greet me.

“Suddenly I was alone in a strange country. I tried to talk to people at the airport but they didn’t speak English. Worse yet, not one person seemed to recognize me—none of my pictures had ever been shown here. So nobody knew me at all. Nobody! My presence in the Soviet capital wasn’t stirring one little ripple.

I could stare!

“In a way, though, it was wonderful. I was starting on a fifteen-day tour of the Soviet Union and hoping to take intimate glimpses of movie-making techniques and methods inside the iron curtain. So because nobody knew me, I could go where I wanted, do what I wanted, stare all I wanted. For the first few days, anyway. Then I did some TV, I was on the radio, there were stories about me in the news- papers—so by the end of my stay I had no freedom at all. Because everyone knew who I was.”

When the film officials finally caught up with her, they were all apologies. There had been some misunderstanding about her arrival. “They were extremely friendly,” said Kim. “I felt a warm stream of contact between us from the very beginning. All at once everything turned out all right.”

Kim had gone to Russia with many reservations about the attitude and motives of the officials who had invited her there. They were from the Russian Film Association, the state-controlled organization which supervises every phase of movie-making in the Soviet Union. Russia has no independent film producers, no giants like Warners, Columbia, Paramount, United Artists, 20th Century-Fox. There’s only the RFA. Period.

Her main concern, Kim said, was to meet her hosts and deal with them on an equal footing. She had seen and heard how many Americans had gone to Moscow and been embarrassed by the superior and sometimes arrogant pose of Red functionaries. Said Kim, “I decided to meet these people without airs, without suspicions, without an iron curtain around me.” And not for one moment did she regret her decision.

Kim’s first stop was in the U.S. Embassy for a visit with Ambassador Lewellan Thompson. Then she was off on her tour. It started at a Film Association luncheon in her honor. Russia’s top film stars, directors, and movie officials were present. A top-drawer gathering!

“I was bursting with excitement,” Kim said. “I was like a kid on her first day of school. And that’s how I made my first boo-boo. I looked at a portrait on the wall and asked, ‘Who’s that?’

“There was a long silence. Everyone stared at me. Then one of my hosts replied politely. ‘That’s Lenin.’ Ordinarily, Kim insists, she can spot a portrait of Lenin as quickly as she can of the late Harry Cohn, her old boss at Columbia. But this one had been painted by a first-year student at Russia’s Film Association school and, Kim swears, it wasn’t a very good likeness. Nevertheless, she recalled, “My face turned red as wine.”

Wine figured in Kim’s next big moment. That night a Soviet film review magazine gave a reception in her honor. Food was piled high on the table and the wine flowed. Glasses were filled to the brim and raised for toasts.

“We were toasting each other to health, happiness—and peace, of course—when Barbara accidentally hit my elbow,” Kim related. And added ruefully, “Have you ever seen a Kelly green dress soaked in rich, red wine?”

Stark silence fell upon the large dining hall. Heads turned, onlookers gaped in horror at the ruined raiment. Kim sat in utter dismay. Suddenly several men seated nearby jumped up and rushed to her with salt shakers.

“They sprinkled salt over my dress from shoulder straps to hemline.” Kim could laugh about it later, but she couldn’t then. “One of them explained, as he gallantly sprayed me with the shaker, ‘Salt will keep it from staining.’ ”

Come as you are!

Kim would have liked to change before her next engagement—a talk to newsmen—but there was no time. She went, as was, to the auditorium where members of the Fourth Estate were waiting.

“I must have carried it off quite well,” Kim smiles, “The press seemed impressed with the latest fashion from the States—pinkish-green crystal spray a la splash. Next day the newspapers commented on an ‘unusual style dress’ I wore.”

After this large first evening in Moscow, Kim retired to the suite assigned to her in the Hotel Sovietski, the capital’s finest. There was television, radio, even a grand piano in her rooms! She was deeply impressed—but also wondered if the Russians had included another modern gadget—a hidden microphone

“Barbara and I had heard so much about Soviet craftiness that we didn’t dare speak above a whisper.”

The two women had no intention of saying anything critical of the Russians, but they did want to discuss one little phenomenon that had come to their attention a bit earlier in the evening at the dinner. It seems one of the women came over to Barbara and asked her to dance. Puzzled as she was by it, Barbara obliged. And now in the hotel room, they wanted to talk about it. But they didn’t dare—the room might be bugged.

“I am ashamed, now, of our thoughts,” Kim admitted. “After that first night we never again even allowed such suspicions to enter our thoughts.”

She found it hard getting to sleep that night. With all its modern appointments, the hotel had no shades! Only lovely white chiffon curtains. Outside, the snow was deep on the ground, the lights on the street glowed brilliantly, and the glare lit up the room like day. She finally went to sleep with a pillow over her face.

Next day Kim was taken to the Dom Kimo, Moscow’s biggest theater, where for the first time a Russian audience was treated to one of her films—“Middle of the Night.”

A dinner party was held in Kim’s honor that night in the Dom Kimo—the theater has huge restaurant facilities on the lower level. Some two hundred guests attended.

“What struck me most was the music,” she told me. “All night long the orchestra played American jazz—and all night long women came up to me and Barbara and took us out to the floor to dance. Of course, by now we were well aware that it’s a fine old Russian custom for women to dance together.”

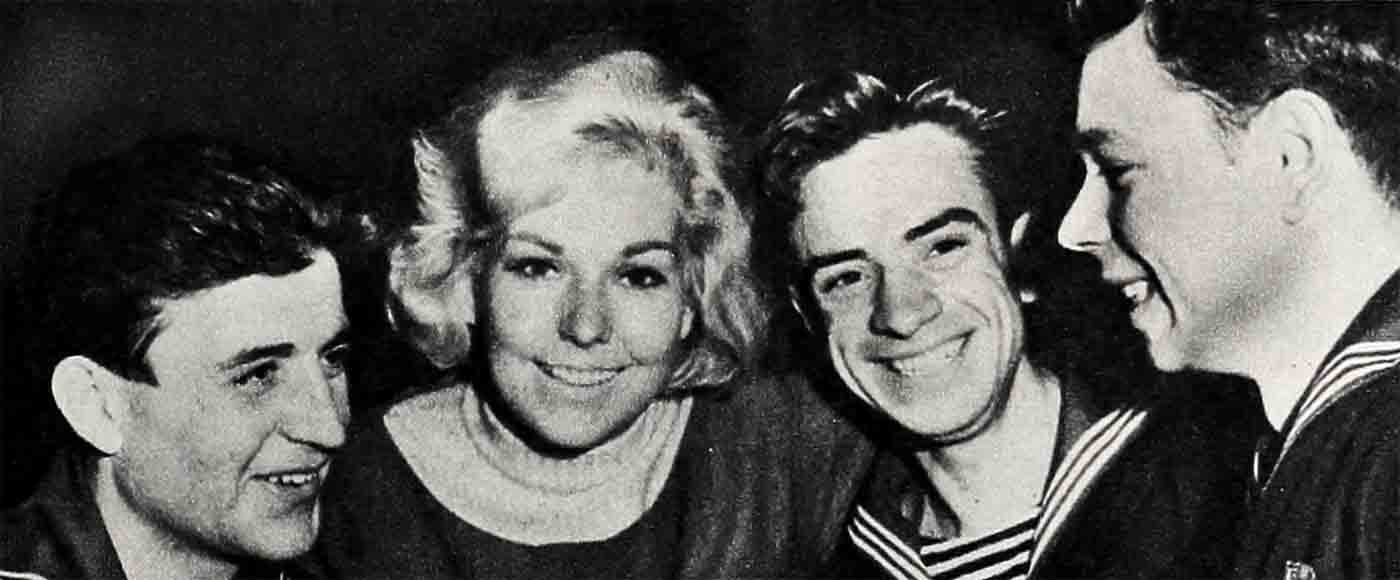

But customs change fast when a gal like Kim Novak invades Moscow. She rocked the staid gathering by going over to the men, one by one, and asking them to dance with her.

Kim was particularly fascinated by one of the Russian male types who emanate from the province of Georgia.

“The Latins of Russia”

“The Georgians,” said Kim, Iter violet eyes mirroring the fire she must have seen smouldering in these men, “are the Latins of Russia. They have black, black hair, dark eyes, white skin and brilliant white teeth. And they’re extremely masculine. Barbara and I played a little game. We’d try to guess who the Georgians were. “I rather liked those Georgians . . .”

No Georgian, hut a fascinating person just the same, was hard-boiled Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s hard-boiled son-in-law, Alexei Adjoubei, editor-in-chief of Izvestia. Kim met Adjoubei in his newspaper’s office in Moscow.

“Someone ushered me into an imposing editorial conference room,” she related, “and suddenly I found myself face to face with a tiger.”

The formality of a brief greeting was hardly over when Adjoubei scowled. “You know, we can bury your country.”

Kim looked at the brash editor, dumbfounded.

“I couldn’t believe my ears at first, for a moment I thought I was listening to his father-in-law! Then I gathered my wits about me and in my most polite manner I asked, ‘What’s the matter with you? Haven’t you enough faith in your Communist system to want to live in peace with other nations? Why must you be so warlike?’

“After three hours of that, Adjoubei knew he had met someone who wouldn’t shrink away from his bullying. By then he was smiling, soft-spoken and extremely polite. Before I left, he autographed a book, ‘One Day in the World’—‘To Kim Novak, with great and friendly respect.’ ”

“Money-greedy capitalists . . .”

Kim feels that on both sides of the picture there’s been distortion by the press, so that we think of the Russians as big white bears and they see us as villainous, money-greedy capitalists.

“And it’s a shame,” she said, “because I think if people knew people, it could help our relations. I don’t mean on the government level—goodness knows we have the most wonderful system of government in the world and I wouldn’t ever want to live under any other kind. But I mean on the people level. I believe in people taking the time and trouble to understand other people—and seeing for yourself, not taking anyone else’s opinion.

“Neither was Russia exactly what I’d read—that everything was so terrible. It really wasn’t that bad. The people were very friendly, very nice. The fashions weren’t great—certainly not up to us or Paris—but not bad. And the Russians try very hard to preserve the arts. Poetry is big there, because they are people with a lot of heart. I don’t think it’s chic here to be a poet—maybe I’m wrong, maybe I’ll have to be filled in like I had to be on the twist—but the poet is probably the most respected man in Russia, and the actor and artist would come next. When they found out I paint and write poetry, that’s all they asked about—not about my movies or my personal life.”

Kim also visited the State Film Institute, which is the state’s principal school for the movie industry’s trainees. It is the Oxford of Russian film training. All aspiring actors, directors, camermen, script writers, electricians, grips and the myriad others who seek a career in movies must attend this school. And each pupil must take full training in every facet of movie-making, no matter in which field he wants to specialize.

“The students live at the school and they live and breathe movies and theater. Only those with the most talent are taken and trained for five arduous years. Every aspect of movie-making is thoroughly taught, from set decorating to camera work, from script writing to acting. A student may enroll with the idea that he wants to become an actor. By the time he completes the course, he has found that his interest lies in directing, perhaps, or camera work. So he becomes a director or a cameraman. And it’s not unusual for woman students to end up as electricians, grips, directors—or actresses.”

Kim is convinced that the training is far more extensive than anything in this country, because each student has been taught to know each job.

There is one system in Russia that Kim does view with reservations, but this is not connected with movies. It has to do with railroad travel—and the strange Russian custom that finds a man and woman, strangers to each other, ending up sleeping together in the same compartment.

It happened to Kim, although her bunkmate wasn’t exactly a stranger. He was Youri Dobrokhotov, a Russian Film Association official who had issued Kim’s formal invitation to visit Russia. Kim’s itinerary called for a visit to Leningrad.

So it came to pass that Kim and Barbara, along with Youri and Bella Epstein, who served as interpreter, got on the overnight train for the seven-hour trip to Leningrad.

“We had two compartments,” Kim told me. “Of course I was going to share one with Barbara, and leave Youri and Bella to share the other in the tradition of their native land.

“But when we got on the train, Youri wanted to discuss my Leningrad schedule, so we went into one compartment while Bella and Barbara went into the other. Barbara was going to teach Bella to play gin rummy.

“An hour or so later, I felt drowsy. I yawned, hoping Youri would take the hint and leave. ‘Okay,’ he said, ‘if you’re sleepy let’s go to bed.’

A startled Kim

“That was what I wanted him to say. But I didn’t expect him to start undressing in my compartment—I had wanted him to go into the next one and send Barbara back.”

Youri saw the startled look on Kim’s face and proceeded quickly to explain about Russia’s co-ed sleeping practice on trains. Although there were two beds, Kim wasn’t about to abide by that old maxim. “When in Russia, do as the Russians do.”

She hastily explained to Youri that all of Barbara’s things were in this room.

“But when we opened the door,” Kim related, “we found Barbara and Bella had gone to bed and were sound asleep. I resigned myself to my fate, but I managed to work it out to a minimum of embarrassment. I went into the powder room and changed. When I came back, Youri still had not finished undressing. He saw the distressed look on my face.

“ ‘All right, turn around and face the other way,’ he suggested. I turned. Youri took his clothes off and got into bed. Then, and only then, did I turn around and get into my own bed.”

Youri, Kim wants me to assure her millions of fans, was a “perfect gentleman.” However, let’s finish the story. There was another problem of a similar nature in the morning. How was that solved?

“I put a pillow over his face and threw on my clothes in record time,” Kim explained. But added, “When I walked out of the compartment that morning with Youri, my face was beet red.”

Needless to say, on the return to Moscow it was Kim and Barbara, Youri and Bella all the way back.

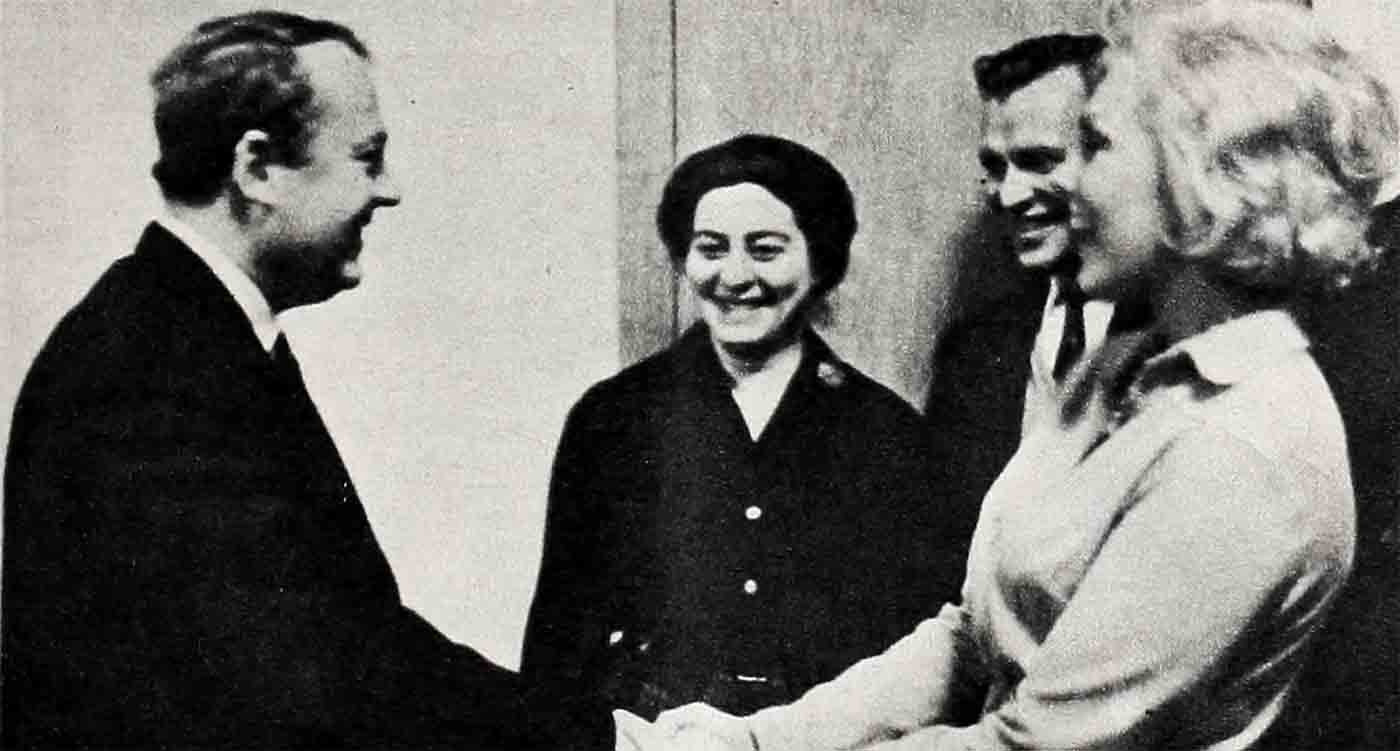

Before Kim left for home, she achieved the goal she had set herself—to lay the groundwork with the Russian Film Association for the joint American-Russian film production, whose story is yet a matter of uncertainty. But this much was accomplished: Georgi Zhukov, head of the State Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, told her to prepare a script. If it is approved by our State Department and by Russian officials, the movie may be undertaken soon.

I asked Kim if she had a plot in mind. She answered, “When the Russians asked me what I hoped to accomplish with a joint film venture, I told them that the peoples of our two countries must get to know each other better—not only politically, but as people. I suggested a love story about a Russian man and an American woman who meet, fall in love, but are kept apart by their political differences. It must be a simple yet real story that could reach the hearts of all people.

“They were basically in favor of this idea, and offered to do all they could to help and support the venture.”

Kim was more than delighted with the results of her trip.

“I had a goal. Not just in making a deal on a film, but to make clear the often distorted picture of Hollywood movie stars. Even in America, we’re thought of as wild and bewildered hollow shells, blundering through our mixed-up blond lives. I was sure that in Russia they had the same, if not a worse view, and I felt it my obligation as an American to set the record straight.

“I never lost sight of my goal the whole trip. I didn’t come away signing any peace treaties or getting any disarmament bans, but I do feel that I learned much and made many friends—I hope for my country as well as myself.”

—BY GEORGE CARPOZI

Kim can be seen in “Notorious Landlady.” Col., and “Boys’ Night Out,” M-G-M.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1962

zoritoler imol

2 Ağustos 2023What i do not realize is actually how you’re not actually much more well-liked than you might be right now. You’re so intelligent. You realize therefore significantly relating to this subject, produced me personally consider it from numerous varied angles. Its like men and women aren’t fascinated unless it is one thing to accomplish with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs outstanding. Always maintain it up!