Elvis Presley: “Hi, I’m Coming Home!”

“I didn’t know a grown man could cry”

I remember, as a small boy I often went hungry. I remember standing outside our two-room shack in the little cotton factory town of Tupelo, looking up toward the huge, red Mississippi sun, and shouting, “Oh, God. Please . . . I don’t want to stay here forever like this.”

I remember my father, who is a man above all else, sobbing because he couldn’t pay all our bills. I remember my mother—who died nearly two years ago—sacrificing her health by working so we could keep going through the rough times.

These are the symbols I keep before me. I don’t forget those early days now that I have so much. I don’t forget that I’ve been lucky. Thousands live like we used to live. I’m lucky that millions of people all over the world wanted what I had to offer—that I now have every material thing I want.

I thank God for all that.

But there were those early days when all we seemed to have was despair.

I don’t know if you knew my mom and dad were both orphans. They married when Mom was nineteen and Dad a year or so older.

I was one of twins, born in the little shack at Tupelo. My twin brother Aaron died when he was just a few months old and I was given the name Aaron after my first name.

My brother’s death hit my parents hard, but they say when one twin dies the other grows up with all the qualities of the other, too. I doubt that, but if I did I’m lucky.

Life wasn’t so great in those days. Dad was a house painter—a good one—but in that small town where nobody had much money, they hadn’t any to spare on peeling walls or blistering paint.

My mother had to work in a dress factory so we could have enough to eat.

Dad, when he could, got truck-driving jobs. We never actually starved, but we came pretty close to it at times.

It may have been very tough, but I didn’t know it then since I had no other kind of life to compare it with.

I know that when I was four or five all I looked forward to was Sundays when we all went to sing at our church. We were members of the Fundamentalist Assembly of God.

I loved the music and sang as loud as I could. We borrowed the style of our psalm singing from that of the early Negroes—a rolling, rhythmic style, with everybody swaying in the church.

This was the only singing training I ever had. I never had lessons.

Probably, this early revivalist type of singing had an effect on my style today. I don’t honestly know.

As I got older I used to sing solos, and my ambition as a young teenager was to be a quartette gospel singer.

I loved the old church filled with sunlight and my mother and father singing beside me. We forgot our problems.

Then, when I was fourteen, my parents could forget them no longer. We decided to go to a bigger town so Dad could get more work.

We left the shack in Tupelo and headed for the big town of Memphis in Tennessee, where we had another two-room home on Alabama Street.

Here, Dad found work. He got a fairly good job in a paint factory, but still my mother had to go out to work to keep us going.

They sent me to the Memphis high school and clothed me as well as any of the other kids, although it cost them a lot.

After school, I worked nights as a movie attendant. That brought in another $14 a week.

Weekends, I mowed lawns with Negro laborers at a half-dollar apiece on the average—it depended on the size of the lawn.

I was strong and liked working hard.

At school, I spent two years in the cadet corps they ran there, but after the first year I wasn’t doing as well as I hoped and my interest dropped. After I graduated, I went to work in a factory, getting up at 3 a.m. for my shift at the plant.

After that I drove a truck. I felt I was growing into a man, and our finances, for once, weren’t too bad.

Then came more trouble when I was about eighteen. My father injured his back, slipping a disc. He came home in great pain one night. He went to the hospital for about two weeks and had to lie still all day. When he finally came home, he couldn’t work for weeks.

This put a big strain on my mother who had got a job at the hospital, a job she didn’t leave for two years. She bathed patients, made beds, scrubbed floors, and poe harder than she’d ever done before.

Her health began to fail. But she kept at it and came home every evening to cook supper, do the housework and mend our clothes.

I used to tell her, “Mom, you shouldn’t have to work so hard.” And she would smile and say, “I love you both so much I’d sooner work for you than anything in this world.”

In the evenings, I tried to cheer them up by playing tunes I’d made up on a guitar my father had bought me for my birthday. It cost him eight dollars and that meant he had to go without smokes for weeks.

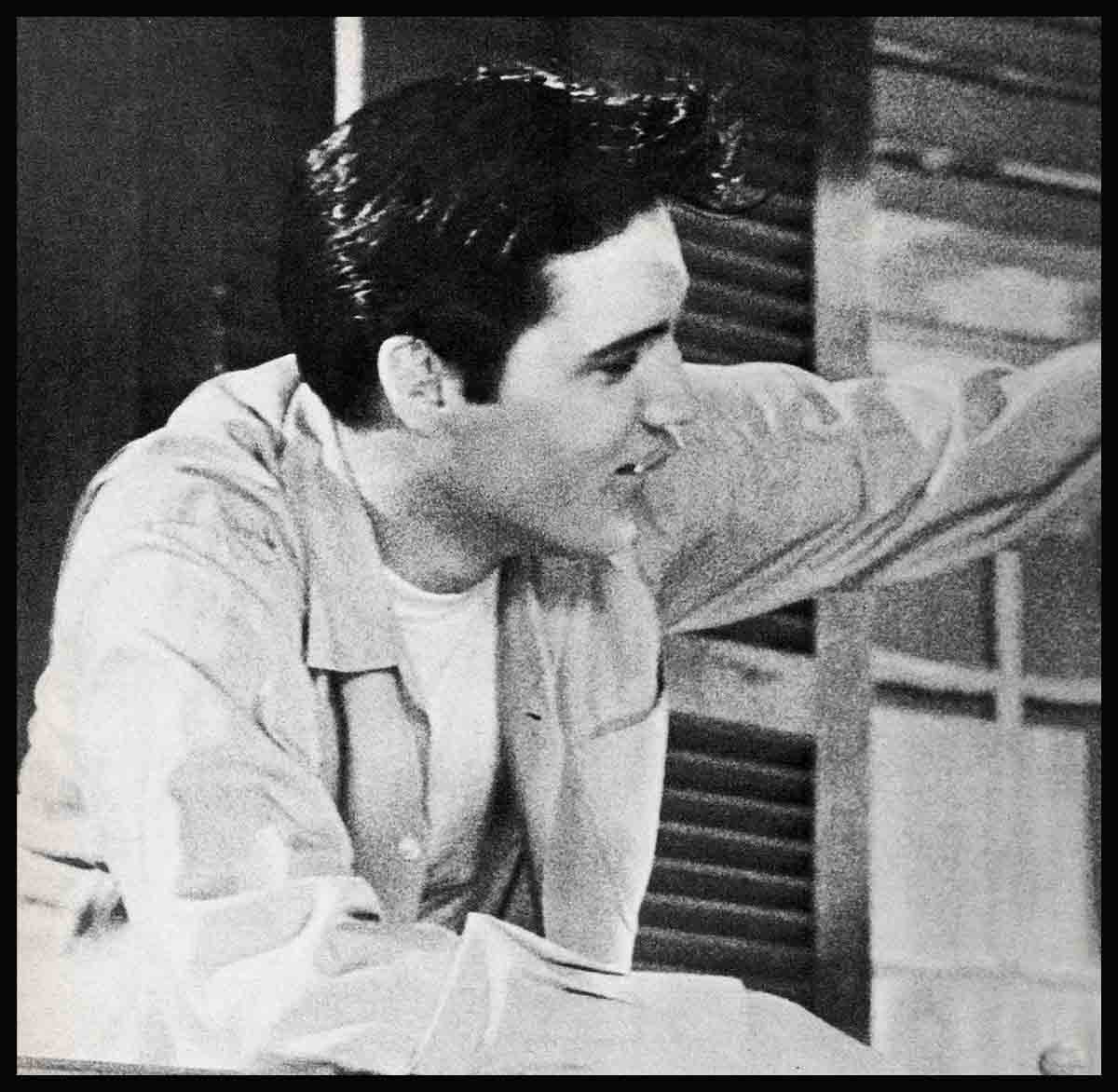

But I never realized our position was getting serious until one night when I came home. My father was sitting on his bed with his head in his hands. I thought he was thinking hard.

When I asked: “What’s up, Dad?” he looked away but he had tears in his eyes. I’d never seen my father cry. I didn’t know a full-grown man could cry.

There had been times when he had been strict with me, times when he may have been too easy, but he was my father and to see him like that made me scared inside.

As I stood there, it was as though something snapped inside of me. I was no longer a boy. I was a man, watching another man suffer. That made me grow up. Looking back, I believe it even changed my whole life.

I knew his injury was worse than he’d told us. He’d tried to laugh it off.

He turned to me and said: “Look son, it’s time you knew the truth. My back is worse than I thought and there may be long periods when I can’t work at all.

“We’re going to have a tough time paying all our bills.”

I didn’t know what to say when he went on: “I never expected to be the greatest man in the world, but I wanted to be a good husband to your mother and a good father to you.

“Now it seems we’re in for some real hard times.”

When he finished talking, I went away feeling helpless. I was eighteen. What could I do? I did the first thing that came to my mind. I got down on my knees and prayed to God to show me some way to help my parents. It was my turn to help them now.

One day I was driving down the Memphis main street when I remembered it was Mom’s birthday soon. I thought I could do something to cheer her up.

I was idling along when I saw a sign which read: “Sun Records Inc. Memphis Recording Services.” I had my guitar in the truck so I stopped and went in.

The owner, Sam Phillips, and his secretary were sitting at a desk. They said it would cost me four dollars to make a record, so I paid and went into a booth.

I sang the first two songs I thought of—“My Happiness” and “Heartache Begins”—and I remember feeling very silly in there all on my own, singing only to myself.

When I came out, Sam Phillips said: “You got a fair voice. I’ll call you some day. We’ll try out a number or two.”

He called just one year later.

Well, we tried a few slow ballads for a couple of hours, then, during a coffee break, I tried to make a few pals laugh by singing a fast rhythm and blues number.

They got to clapping, then Mr. Phillips suddenly yelled loud and bounded over.

“Boy, that’s great! That’s how you gotta sing. Let it go. Sing up a storm.”

I made five more records for Sun Records after that, all of which were played on the local radio station.

Then came the day I was invited to make a personal appearance.

It was in an outdoor theater in the town. The main performers were opera stars.

When I went on, I made myself forget me. I sang “That’s All Right Mama” and gave it all I had.

Suddenly the teenagers at the back of the audience started screaming.

I finished—and they screamed louder and louder. I was scared. I didn’t understand it.

But, when I knew they were screaming for me, I felt something big and wonderful had begun.

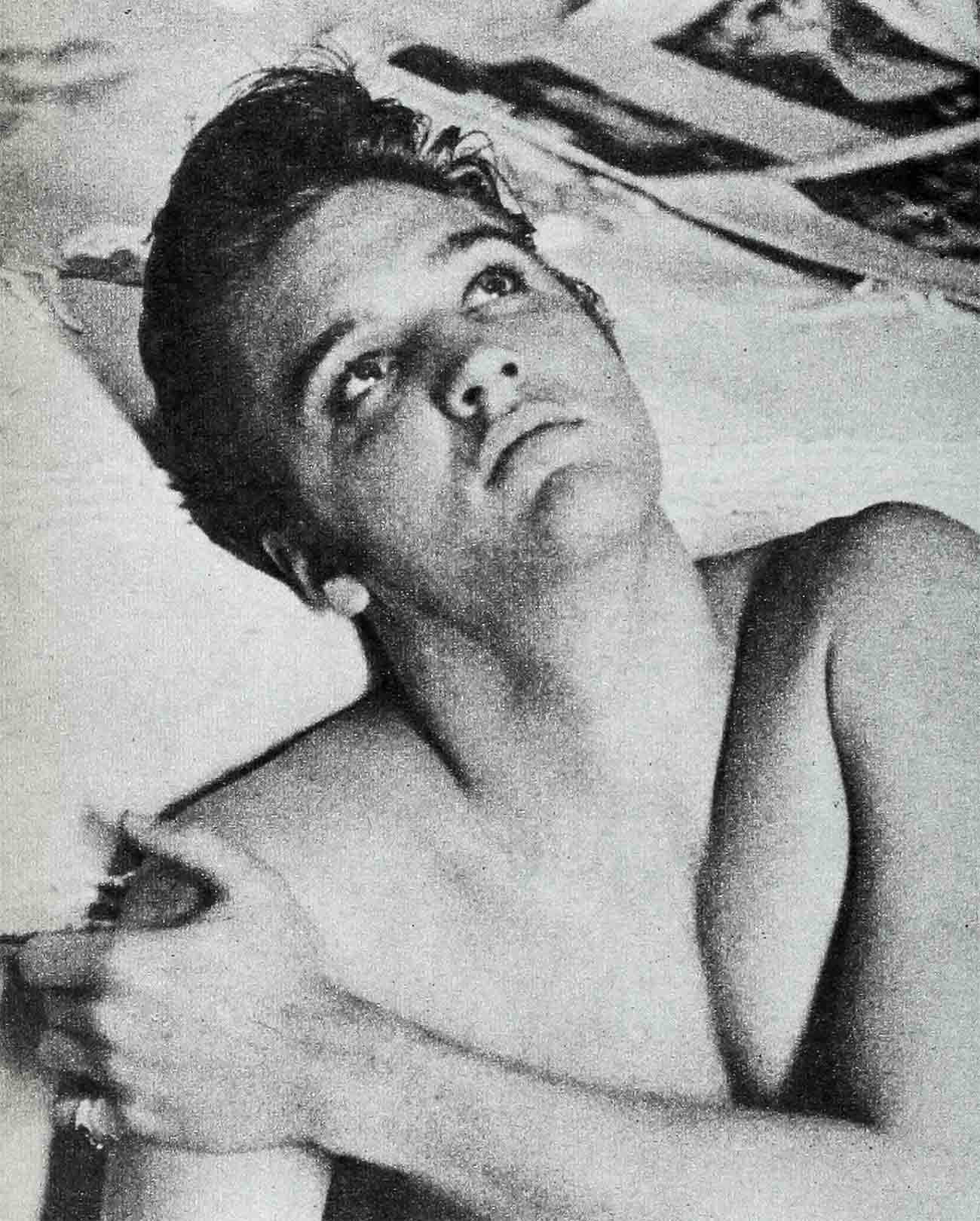

I slept badly that night. I had nightmares full of screaming people, but they weren’t frightening dreams because I knew that those screams meant the end of money worries for Mom and Dad.

The poverty we’d known all our lives and had come to accept, was going to end. For years my mother had ruined her health slaving for me and for Dad while he was out of work with an injured back. Now my chance to help had arrived.

First, I was signed up by showman Col. Tom Parker, one of the shrewdest managers in the business. He got my contract with the small Memphis record company taken up by RCA Victor.

My first record for them was “Heartbreak Hotel.” It hit the top and was my first record to sell over a million.

For the first time in his life, Elvis Aaron Presley and his parents had money to spare. I went kind of mad.

I bought one Cadillac, then another. I moved my folks from the two-room shack on Alabama St., Memphis, to a $30,000 mansion, then to our $100,000 home just outside the town.

I went on long tours. Everywhere, the kids went crazy. Police at every town were reinforced when I sang. I never liked that kind of fuss, but there was little I could do about it.

Church leaders said my style was immoral. I didn’t and still don’t see any harm in my style. Soon the fuss died down.

Then, in Wichita Falls, Texas, fans broke every window in my car and kept the broken glass. In San Diego girls covered my car with their phone numbers written in lipstick. It was the same everywhere we went.

One day, I drove my car into a filling station.

Fans trapped my car. I couldn’t drive away, so I just chatted, asking them to let me go.

The garage man hit me on the back of my head and said: “Move on, son.”

I got mad. I clipped him as he had clipped me. A fight started, police broke it up and he and I appeared in court. But the charges of assault against me were dismissed.

The next month, a nineteen-year-old boy called Louis Balint came up and attacked me. He said he was jealous because his wife always carried my photo in her jacket. He was fined $8 for that. Later, he said someone connected with me had told him to do it to get me publicity.

It’s possible someone did play a joke on him, but nobody connected with me told him to do it. That sort of publicity can only do harm. We’ve never rigged anything.

All the attacks being made on me upset my mother. She went out less and less.

I told her the attacks would stop if I lived properly. Now, of course, they have.

I never thought my style “wicked.” When I start to sing I don’t know what happens to me. Maybe it’s the music, the but to the rock ’n’ roll beat I just have to move my hands, feet, knees, legs, head—everything.

Because some young guy has his hair done in my style, then commits a crime, who gets the blame? Elvis Presley.

If the kids want to yell my numbers, well, let them. Get young people in any part of the world together in a group and they won’t sit like statues.

Wicked? I don’t even smoke or drink. I was terribly nervous before I did my first TV show. I sang “Shake, Rattle and Roll” and “Blue Suede Shoes” and, again, just let go with the music. Again there were attacks in the papers, but I felt I could live them down. As the months went by, it was like a dream. Every show I did they screamed louder and louder.

Our years of poverty were over. I now had a way to repay my mother and father for the sacrifices they had made for me.

In this business, life goes so fast that important things (like remembering your parents) can slip by. I made it a point not to let that happen.

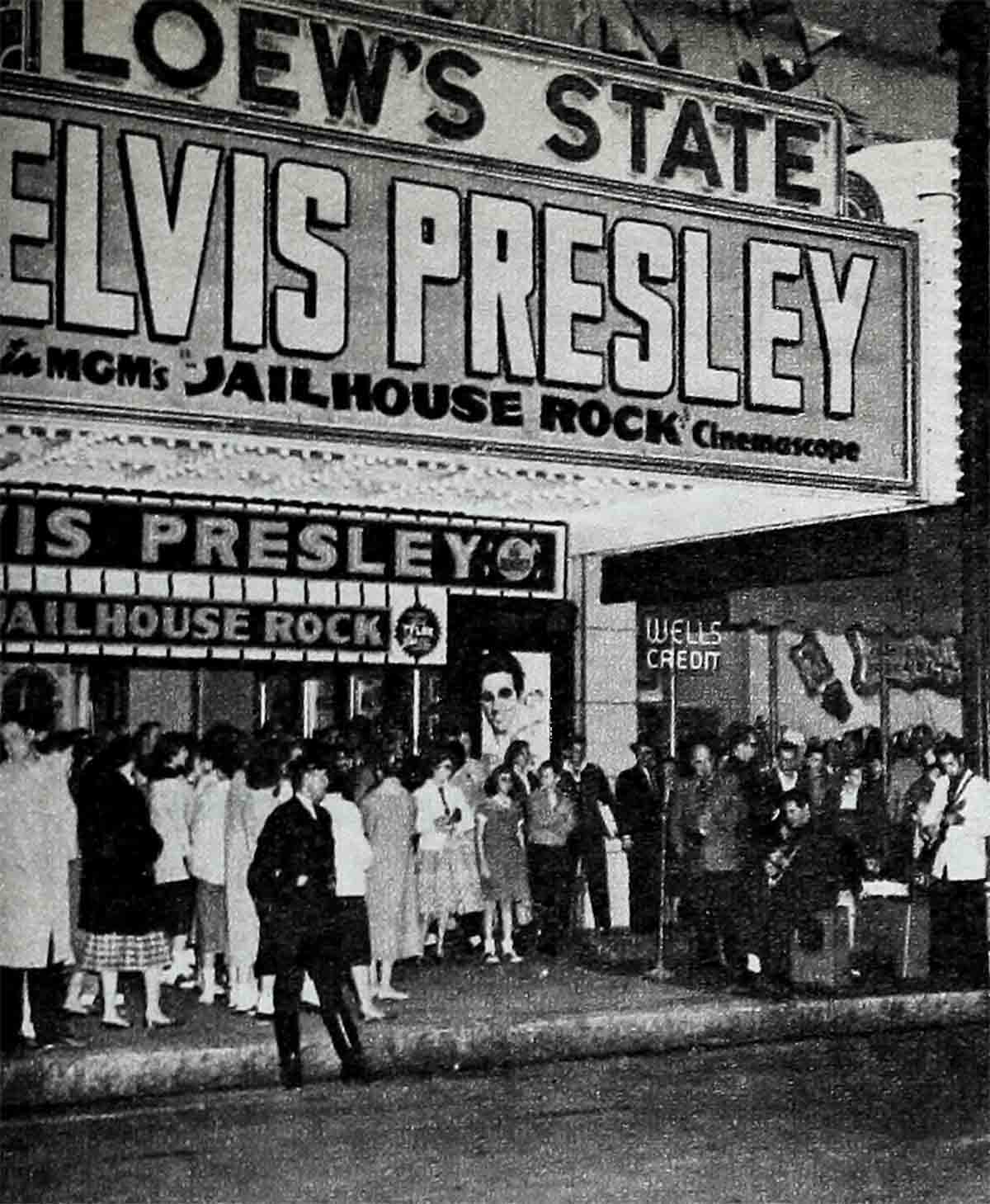

When Col. Parker told me 20th Century-Fox wanted me to co-star in a film with Debra Paget and Richard Egan, I was overwhelmed. They called the film “Love Me Tender,” and wrote in three songs for me.

Looking back, I don’t think it was the right part for me. A whole lot of people wrote saying they were disappointed.

I was happier with “Loving You.” Many critics said I was a good actor—that was praise I wanted.

Then I got my draft notice for the Army.

I was stationed for twenty-two weeks’ basic training at Fort Hood, Texas, and I did my fifteen-mile forced marches with a sixty-five pound pack on my back, same as the other guys.

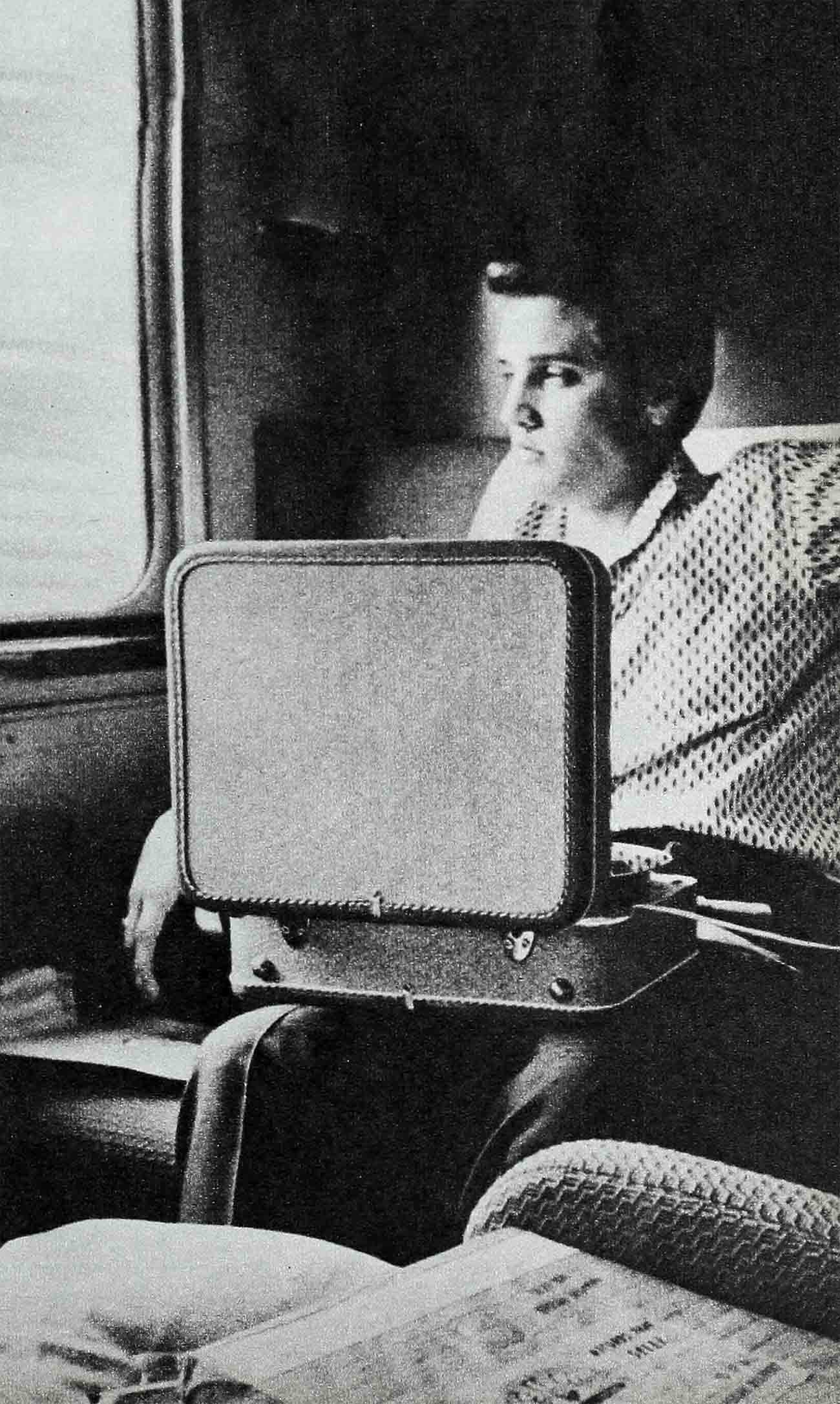

The person who felt it the most, when I was called, was the person who gets hurt first in every happy family—my mother. Her health had been failing.

She came to see me but on the way home, she had a bad heart attack in the train.

She was taken to the hospital where she spoke to me by phone every day when I came off duty. All I wanted to do then was to see her. I went in for emergency leave and got it.

My father met me and took me to the hospital. I remember his face was white and strained, and when he smiled I knew he didn’t feel like smiling.

He just said, “She keeps asking to see you, Son.”

I went in to see her. I’d never seen her look so bad, but she was happy. She held my hand and we talked for as long as the doctors would let us.

I kissed my mother goodnight and promised to return first thing next day. Then I went to our home. I didn’t sleep.

At 3 a. m. the phone rang. I knew something had happened and for a while I tried to pretend it wasn’t ringing. But I knew who it was.

When I picked it up, my father said: “Son, she’s gone . . . she’s gone.”

I pulled on some clothes and raced to the hospital. I can’t talk about this. I can’t describe the feeling of desolation—she had died when we were going to have so much, after so little.

She was forty-two. She had lived just long enough to know her years of sacrifice had not been in vain.

But all I wanted was for her to be alive, alive to share all the good things that were coming . . . the things she deserved.

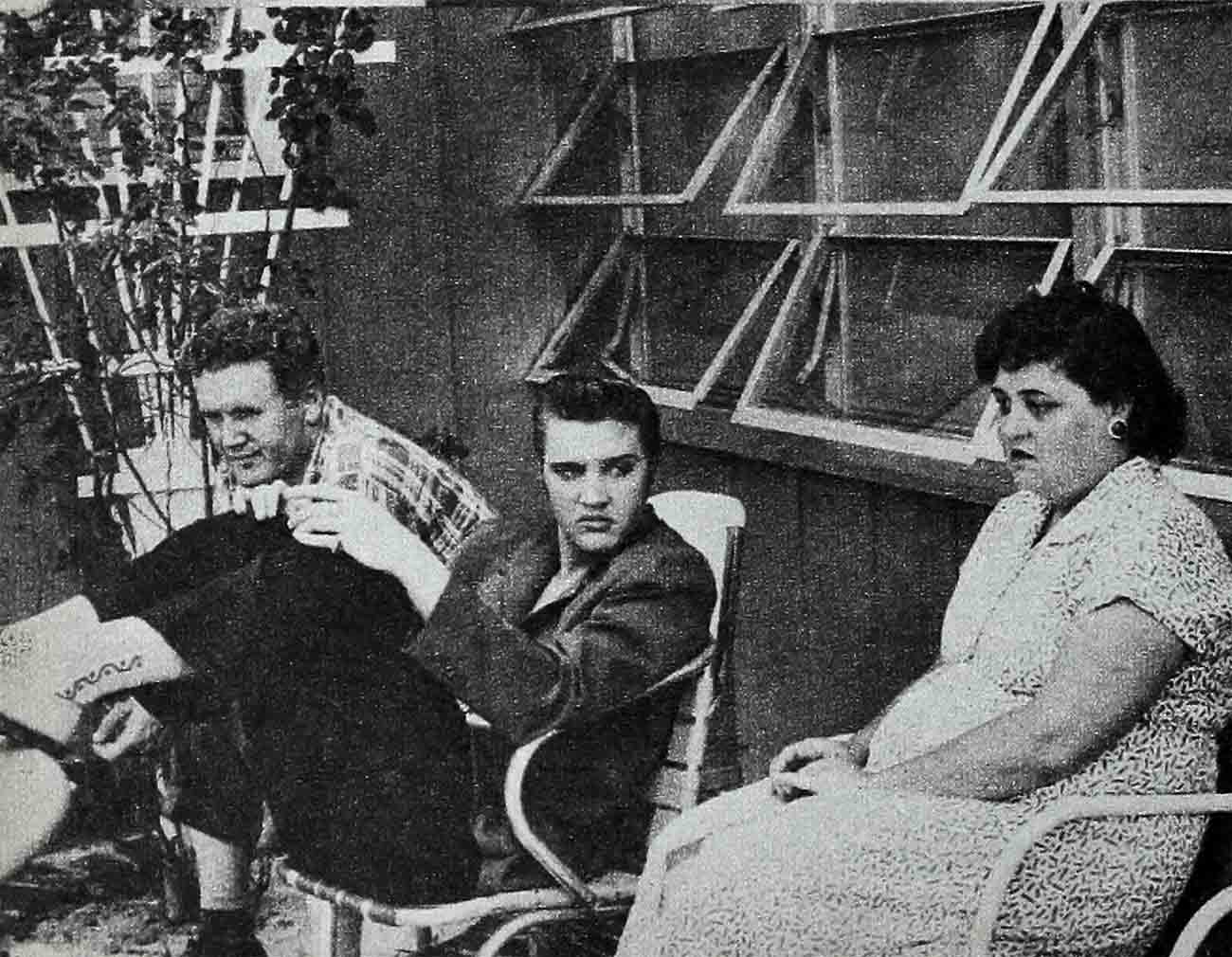

Then I resolved I’d never let my father—nor his mother who lived with us—be alone.

As long as they wanted me, I’d be there.

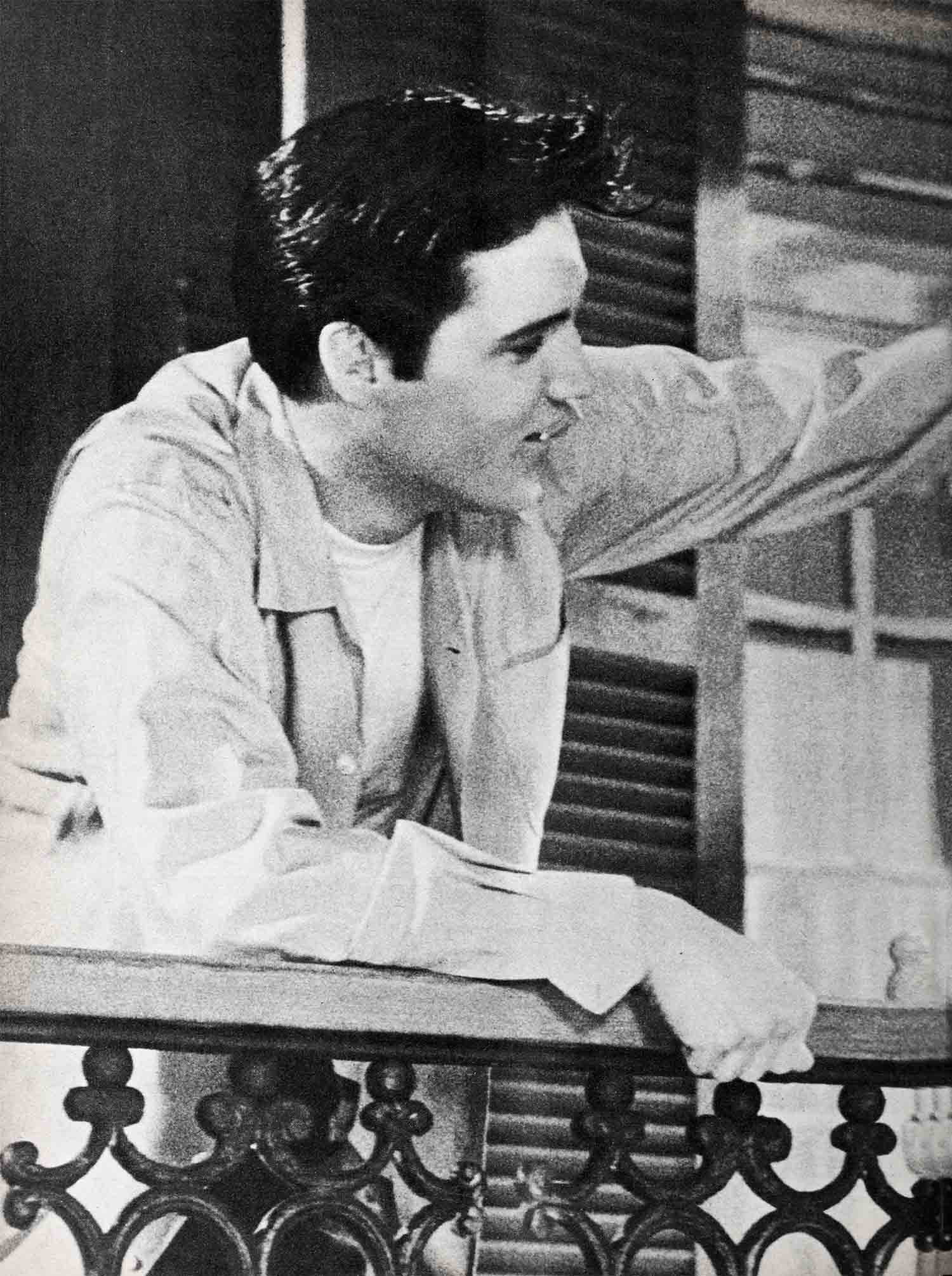

I knew I would soon be shipped to Germany. We decided to close up our Memphis home and my father and grandmother joined me in Germany, where I was stationed. I wasn’t going to have them moping, alone, without me at home.

I take advice from Dad. I was a normal teenager—often thought my folks were preventing me from having fun. But I passed that stage pretty quickly.

I soon found out that, because they have experienced the stage of life you are reaching, they know the way you think.

I think Dad got a bit bored with life here in Germany when I wasn’t with him.

But I was just like any other private in the Army. It’s the only way to be. The boys thought Private Presley E. ASN 53310761 would stay by himself, not have anything to do with anyone, and not be friendly.

But I was never stand-offish. I like people and I don’t like to be alone.

I didn’t consider myself a special soldier. If any one man says the Army’s wrong and he’s right, he’s in for a bad time.

I’ve been asked a lot about girls. Asked if I want to get married, Sure I do . . . one day and when I meet the right one.

I don’t mind whether she’s a redhead, blonde or brunette as long as she’s truly feminine. I like a girl to look up to me. But I guess most guys feel this way.

I’ll be leaving the Army soon. I’ll be coming home. But before I do, I wanted you to read my story; I wanted you to understand why I’ve changed. I think being in the Army, going new places and meeting new people, has helped me to grow. And it’s also given me a chance to get a new perspective on myself. Now, looking back over the past few years, I see how much I’ve grown since that day I saw my father cry. Like I prayed that day, I feel I want to go down on my knees and pray again . . . that people back home will still want to hear me. Because I want to continue giving pleasure to them the way I was finally able to give to my own family. I hope that folks won’t think I’ve changed too much, that they’ll see that, no matter what new experiences I’ve had, basically I’m still the same person. And I do hope that folks haven’t forgotten me. I haven’t forgotten them.

—ELVIS

WATCH FOR EL IN “G.I. BLUES” FOR PAR. BE SURE TO CATCH HIS OLD FILMS WHICH ARE BEING RE-RELEASED. HE SINGS ON RCA VICTOR.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1960