Ann-Margret’s Life Story!

PART II

Last month, Part 1 of Ann-Margret’s life story described how she and her parents left their native Sweden and came to live in Illinois. In Wilmette, a high school teacher told Ann-Margret, “I predict Hollywood for you” A short time later his prediction came true. Now read the concluding half of Ann-Margret’s life story by Ed DeBlasio.

While still in high school,” Ann-Margret says, “I realized that I wanted to be a professional entertainer after I graduated. And though I’d sung at many weddings and parties and on various amateur shows, I realized, too, that I’d better get a professional job if I really wanted to get started. So—one summer when I was seventeen—I went to all the agents’ offices in Chicago. Now you know how humid and hot it is in Chicago in summer. So I put a sheath and high heels on every day and every day I’d get exhausted and upset, because they all said they’d take my name and call if anything came up. But none of them did call. And then finally I came to the one man, Hal Munro, who said, ‘Okay can you get to Kansas City and the Muehlebach Hotel by Saturday night? And I was in shock. Kansas City is away from Chicago. The job was for one month with Danny Ferguson’s band at $98 a week. I didn’t have the clothed for the job. But everybody was so wonderful. My cousin Anne lent me some dresses—she was an airline hostess then and I’m sure that, at one time in my life, she must have lent me about one-half of her wardrobe. And Sharon Lauver lent me a beautiful cocktail dress her very best dress, a darling pink cock tail dress, for the opening. And the other girls lent me other things. Finally, one morning, my Mom and Dad and I left for Kansas City. My sweet Dad drove us. My parents are so unbelievably wonderful. I’m going to do everything in my power to make them as happy as they’ve made me.

AUDIO BOOK

“You know what my Dad did? He drove all the way to Kansas City and then he drove back, by himself, because he had to be at work Monday morning My mother stayed with me. It was such confusion that weekend. I had to learn fourteen songs in one afternoon because I didn’t know a single one that Danny showed me. But it was oh so worth it! Because it was, as I said, my first professional experience. And because I learned two very important lessons from that experience, both of which I shall never, so long as I live, forget.”

The first of the lessons was a professional one.

Ann-Margret had been with the band for about a week now and she thought that she knew just about all the ropes. That is until the night she was sitting down and thinking hard about all this and missed her cue.

‘I’m sorry, Danny,” she said to her boss softly as she rushed to take her place.

“You should be,” Danny said—not so softly. He signaled for one of the men to take his place, then for Ann-Margret to follow him to the rear of the bandstand. And he began to let her have it, then and there . . . good and loud, too.

“Please, Danny, please,” she said, after a few moments of this, “I wish you wouldn’t holler at me. I come from a home where there’s never any hollering. My father never, never raises his voice.”

“Really?” said Danny. “Well, how do you like that? But the only difference, young lady, is that I’m not your father and I do raise my voice. And that this is show business, not your living room. And we do quite a bit of hollering in this business. Especially when we pay somebody to work for us and when we expect that person to be on time for us. Now,” he went on, “you get back out there on that bandstand, and you just sit there! No singing this time. Just sit there and while you’re sitting you tell yourself over and over, ‘This is show business and we’re never late in show business. This is show business and we never let anyone down in show business.’ over and over. You understand? I’m serious about this.”

A worldly lesson

Ann-Margret nodded. “And,” Danny said, his voice suddenly softening, “do me a favor, will you? Take this handkerchief and wipe those tears away. And don’t do any crying out there, either. First of all, it’ll make me look bad. And, second, that stuff on your eyes will start running down your cheeks and you’ll look pretty darned funny.”

The second of the lessons Ann-Margret learned was a worldly one:

It was early one evening, and she was sitting alone, reading, in her hotel room. (“It was really a nice place,” she has said of the hotel, “where a lot of entertainers stayed, but it was in a bad section.”)

After a while she thought she heard some noise from the direction of the parking lot next door. She rose to look.

She saw, first, a very old man with a wooden peg leg hobbling around the parking lot, a whisky bottle in his hand. “Come on, come on,” he croaked, groping, “come on out here and fight.”

A woman ran after him, a youngish woman. “Pa,” she shouted. “Pa. You’re drunk. He didn’t do nothing.”

A young man’s form appeared suddenly from behind a parked car. “all right, I’m here,” he called. “But look, I didn’t . . .

He said no more, however. Because, in an instant, the old man had hurled his bottle against the young man’s face.

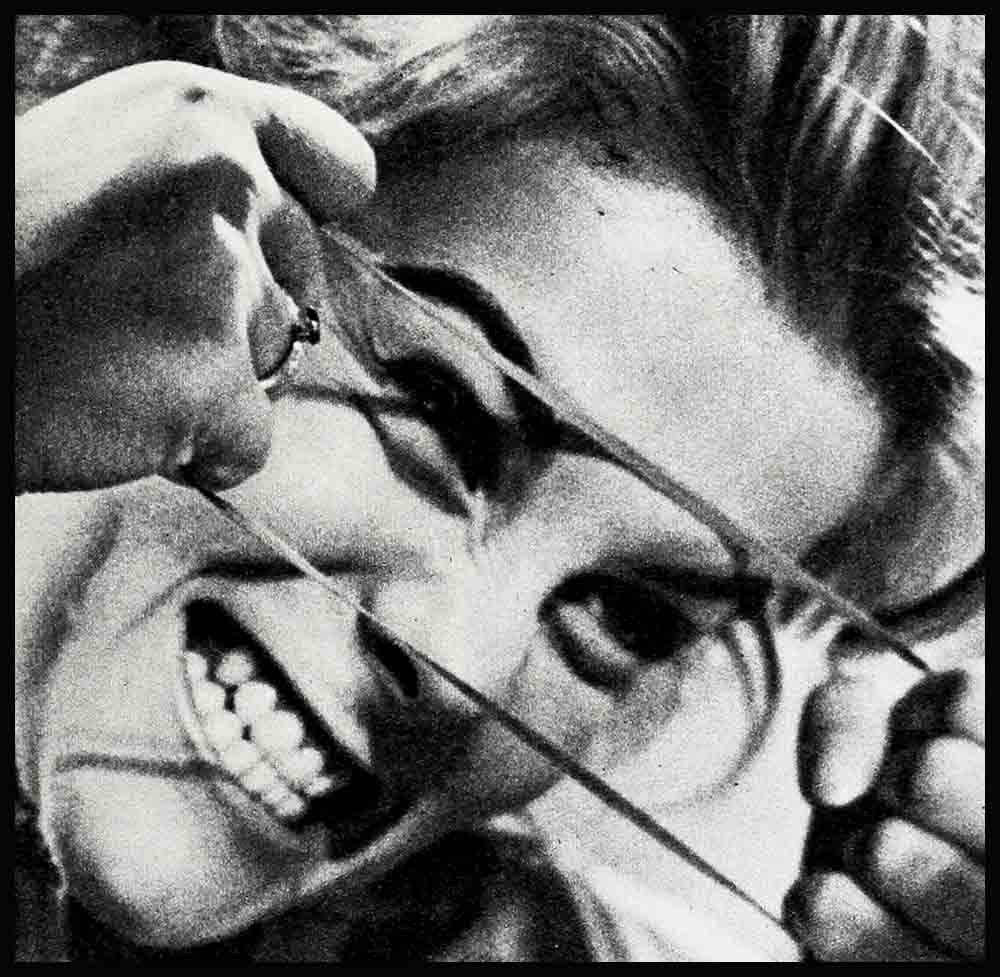

“The blood, oh Mamma, you should have seen the terrible blood,” Ann-Margret was weeping in her mother’s arms a little while later. “It came pouring from the boy’s cheeks. And then the old man went over to grapple with him and he got cut on the broken glass, too. And his hand got gashed. And there was blood, blood, all over.

“Oh, Mamma,” and she was weeping uncontrollably now, “I want to go home. I don’t like it here, this city, this place. I don’t like to see fighting and ugliness.”

Mrs. Olson let her daughter cry it out.

And then she said to her:

“Of course, Ann-Margret. Of course we can go home, if you really want to. And you can stay there. And say goodbye to the entertainment business. And not sing outside of your own little town anymore. Of course we can go.

“But first, Ann-Margret, understand this. What you have seen tonight is a part of life. Your father and I, this we have kept you away from as much as we could. But we cannot keep you away from it forever. You are older now, Ann-Margret, a young woman. And what you have seen tonight is simply a part of the grown-up world which you will soon have to enter—no matter if you are in Wilmette or Kansas City or Stockholm or anywhere. Yes, it was ugly what you saw tonight. Dirty and bloody and ugly and sad. And once, long ago, when you were a little tiny girl, your father wrote to us and he tried to tell you a little of what you might expect from life.

“I don’t remember his words exactly.

“But I think they went something like this:

“ ‘I know that one day our baby must learn that there is sadness and disappointment in life—for that is a part of life. And I hope that if we teach our child but one thing, we will teach her that sadness and disappointment need be only a temporary thing when one is strengthened by goodness and love and honesty with oneself and with others.’

“Is there any sense in those words of your father’s, Ann-Margret?”

“Yes.”

“Do you still want to leave this place and go back home?”

“No.”

“You are sure?”

“I’m sure, Mother, absolutely sure.

The beginning . . .

“I continued singing all through the rest of high school,” Ann-Margret says, “and then through the year of Northwestern University that I attended. I had intended to go to Northwestern for two year s. But Scott Smith, a pianist, heard me singing at the Theta house one day and a few weeks later he asked me if I’d like to join him and a drummer and bass player, also from Northwestern, in a job at a club in Las Vegas. My parents knew the boys, all good boys, so I knew it would be all right with them. As for me, I was a little hesitant at first. I had gotten used to hearing things that sounded real good and all of a sudden they’d fail through. But, fortunately, I found myself saying yes. Though, at first, when we first got to Nevada, it didn’t seem fortunate at all . . .

“Sorry,” said the Vegas club owner. “There’s no job for you here.”

“But you said last week. . . .”

“That was last week. This week we’ve decided to hold over the combo we got.”

“But . .

“Look, fellas. Look, girlie. I tell you what I’m gonna do. Here’s the name of a club in LA. I know the owner. He’s my best friend. I know he’s looking for a nice clean-cut group like you. So just tell him I sent you, and you’re sure to get a job. Now get goin’, will you?”

And the following mid-morning, when they arrived in Los Angeles after another overnight drive, the treatment they got was exactly the same.

“Sorry.”

“But . . .”

“Look. This crackpot in Vegas? I barely know him. He sends you here for a job? He’s a nut, that’s what he is. Look at my place, will you? It’s two by four; it’s nothing. The only music I want comes from that juke-box over there in the corner. I’ll stake you kids to a cup of coffee. You’re too young for anything stronger. But then, please, leave me alone and go find yourselves a job someplace else.”

Remembers one of the troupe: “We found an agent that same day and he said, ‘Call me and I’ll try to find you a job.’ So every day we called him at 11 A.M. and at 5:30 P.M. This went on for about two weeks and we still didn’t have a job. Meanwhile, we had about five dollars left between us. It was hardest on Ann-Margret because she had to have a room by herself, being the only girl, and she had to pay the most money. We got so discouraged that we started going in and out of agents’ offices ourselves. We didn’t know anyone, but just looked in the phone book for the names of agencies. And, finally, through one of our contacts, we got our first job in Newport Beach, at the Villa Marina. They hired us for one week, but liked us so much they kept us for three. This was a real good break for all of us. And, as it turned out, it was a sensational break for Ann-Margret.”

Her pay at the Villa Marina, first of all, was $139 a week—more than she’d ever earned before.

Then there were the celebrities, the people with contacts, who dropped by the club for a drink or dinner and who remained to listen to the little gal from Illinois sing, song after song, hour after hour. Among the admirers were TV producer Don Sharp, the Edgar Bergens, the Henry Mancinis, and Ward Bond.

Good luck charm

Following the three-week stint at the Villa Marina, Ann-Margret and the boys were immediately booked by the manager of the club at the Commercial Hotel in Elko, Nevada (two weeks). From there it was the Riverside Hotel in Reno (booked for two weeks, they stayed six).

And then, less than four months after they’d practically been kicked out of town, an offer—a genuine offer this time—came from Las Vegas, and the Dunes Hotel.

Ann-Margret and the boys opened in a small room off the lounge and casino.

But there was nothing small about the reception they got that opening night.

“Mamma . . . Daddy,” she said over the long-distance phone that night. “A fellow named Bobby Roberts was in the audience and he asked if he could be my manager. Me! I’ve got a manager now . . .”

Then: “What? Oh, what did I wear? Oh my gosh, I didn’t even think much about that. In Elko I bought an orange sweater that was on sale, for five dollars. And I have my old black capris. And so that’s what I wore. Yes, very simple. And kind of shabby maybe, too, huh? But nobody seemed to mind. Honest. They just listened and then clapped and asked for more . . . and oh Mamma, oh Daddy, I’m sooooo excited.”

“I’m so excited!”

Bobby Roberts turned out to be a good new manager for Ann-Margret.

And the black capris and five-dollar sweater a good new charm.

A few weeks later, back in Los Angeles, Roberts took his client for an audition with George Burns, who was preparing to open soon at the Hotel Sahara in Las Vegas.

“I like that pants and sweater combination. Miss,” the cigar-chomping Burns said to Ann-Margret when they met. “If you sing like you look—you’re okay.”

With Scott Smith accompanying her on the piano, Ann-Margret sang “Bill Bailey,” “Misty” and “Mack the Knife.”

Says someone who was there: “It was amazing. This sweet little thing with the long hair—I thought she was crazy to pick those songs when she started. But once she started, wow—the sweet young thing turned into a gorgeous animal, and you’ve never seen such sex. When she sang she wiggled everything from her toes on up.”

Said George Burns, immediately after he’d heard the set, even taking the cigar out of his mouth for the occasion: “Miss? Do you want to work for me?”

“Yes,” said Ann-Margret.

“Great.” Then: “Miss—or what’s that long name of yours again?”

“Ann-Margret,” she said.

“Ann-Margret, before you came in here today, I had this whole show of mine set. I need a girl singer like I need a pack of cigarettes. But you have an unusual style, Miss Ann-Margret. Very unusual. And right during that first song of yours I decided to make room in the act for you.

“Now,” and he put the cigar back into his mouth and let out with a long puff, “how’s that for show business?”

“I will never forget it,” Ann-Margret says. “We opened on December 23, 1960. And what a night that was. I sang my three songs—it was the first time I’d sung solo in such a big room as the Congo Room. And then Mr. Burns and I did a little soft shoe dance, which he calls a sand dance; he has sand in his pockets and he spreads it around and gives some to me and I spread it around and so on. Oh, I got so many telegrams from my friends in Wilmette that night. And beautiful flowers from my cousin Anne and her roommate Nancy. The only disappointment was that my parents could not be there. But when I phoned them and told them I had worn my old capris and orange sweater, still, just for good luck—that the pants were so shiny by this time and that I had to sew them in four places, they just laughed. Of course, two nights after we opened it was Christmas and I was so lonely for my folks. I pretended I would ignore it was Christmas, except for my prayers in the morning. But that night when I went back to my room after the show, I could see that my door was open and that there was a little Christmas tree on my bureau with tiny ornaments and tinsel beside it. Scott Smith had put it there. And it made me feel so good. And I said to myself, ‘Yes, it is Christmas, it is.’ This was, in a way, the nicest present I had ever received. The next nicest came a few days later when I received word from Mr. Bob Goldstein of 20th Century-Fox Studios in Hollywood that I was wanted there for a screen test. The test was set for Friday the thirteenth of January. And I was very nervous—for reasons more than just the date. . . .”

Their eyes popped

Ann-Margret arrived at the studio at exactly 6:25 that morning.

She was five minutes early—and just as well. Because that gave her five extra minutes to relax before the most exacting and grueling day of her life got under way.

Which it did at 6:30 promptly when di- rector Robert Parrish came up to her, introduced himself and the two people with him: “This is Shana Alexander and Grey Villet of Life magazine. They’re going to take pictures of you and interview you as the day progresses— little idea of ours which will make a nice picture story if and when you get the part.

“Now here,” he said then, handing Ann-Margret a manuscript. “Have you ever seen one of these before? It’s the script of ‘State Fair.’ ”

From 6:45 until 7, Ann-Margret looked over a penciled portion of the script.

And then she was whisked to the Fox costume department where she was fitted by designer Don Feld.

“These tights are good for you, Annie,” said Feld, explaining the outfit he’d chosen for her. “At no time do we ever see less than a complete leg. Is that your normal working foundation? Your normal bra? Is it pushing you up or something? You don’t look at ease . . . You’re a little bit nervous and breathing hard? Well, I can’t blame you. Good luck today. And for just a few minutes now, stand still, will you please, Ann, Annie, Ann-Margret?”

At 7:45 director Parrish returned and led Ann-Margret to Makeup.

On the set, finally, at a few minutes to 9, Ann-Margret showed ’em.

First she. sang “It Might As Well Be Spring”—very innocently, very demurely. And then she belted out “Bill Bailey”—wiggling from head-to-toe and toe-to-head.

And later, that afternoon, Ann-Margret worked on a few key scenes from the script. Recalls Parrish about those hours: “She was very good. She was a pro. She knew how to follow direction and do exactly what I wanted. The only trouble she gave me was when it came time for her to kiss Dave Hedison a few times. She said it made her feel embarrassed in front of so many people. Well, I had a little talk with her. A few of the boys pretended not to look, to be busy with something else. And from there on, things were fine again.”

At 7:30 that night the test was finished and Parrish walked over to Ann-Margret and said: “I wish I could let you know the answer now, Annie. But there are others who have to see the test, so we won’t know for a few days. Meanwhile, tell me, are you excited?”

Ann-Margret yawned. uncontrollably. “Yes,” she said then, quickly.

Parrish laughed.

They shook hands.

And Ann-Margret drove out to the airport where she caught a plane for Chicago and home—and a few days of waiting.

Couldn’t jump any more

“I waited and waited and was on pins and needles,” Ann-Margret says. “I waited for about five days. Meanwhile I had gotten a telegram from Mr. Parrish saying he had just seen the test and that it was great—just as he thought it would be. Then, a few days after that, he phoned and said that as far as 20th Century-Fox was concerned, they wanted me, and now it was up to my manager to agree to terms. Then, about ten minutes later, there was another call and it was Bobby and he said Pd gotten the contract, they’d made the deal. And I just jumped up and down, up and down, until I couldn’t jump any more. I went off to Hollywood again about two weeks later. I made ‘State Fair’—part in Hollywood, part in Texas. Then there was the wonderful break of my appearing on the Academy Award show. when I sang ‘Bachelor in Paradise,’ and from which there was so much good reaction. Meanwhile I had also made the picture ‘A Pocketful of Miracles,’ in which Miss Bette Davis starred. She was such a nice woman. She really helped me so much. Then I began to make records, too. ‘Lost Love’ was the name of my very first single. And I could just see all my Swedish aunts going into record shops and asking for ‘Lost Love’ by Ann-Margret. It’s so funny because they never buy rock’n’roll records.

“And then oh so many other wonderful things happened. I learned, for instance, that I would soon play one of the female leads in ‘Bye Bye Birdie’ for Columbia Studios. And I meanwhile had gotten a very nice apartment. And, thank God, my father recovered from a slight heart attack he suddenly got one day in Wilmette and he was able to retire from his job and he and my mother were able to come out here to California and live with me. And . . . I began to meet so many nice young men out here. And I began to go out, much as I did back home. And have such a wonderful, wonderful time. . . .”

Ann-Margret became engaged to one of the nice young men for a short while.

His name was Burt Sugarman, and he was young, and rich, and as good looking as any leading man.

Ann-Margret, who’d gone out with many fellows before, had never before gone steady; had certainly never been in love before. But then along came Burt. And the feeling was there, finally—though not at first, most decidedly not at first.

Recalls one of her girl friends: “I was in Hollywood visiting Ann-Margret at about this time. Burt had obviously seen Ann in a show and gotten her phone number. Anyway, he’d called her a few times for a date and always she’d said no thank you. And then one evening Burt called and Ann said, ‘I tell you, I have a good friend visiting me here. If you can fix her up with a nice date—then, yes, I’ll go out with you. On a double-date, that is.’ A little while later Burt phoned back and said he’d gotten me a date with Ty Hardin. And that we were all going to go dancing at the Beverly-Hilton Hotel, which was quite an exciting deal for Ann and me. It was a riot the way things happened after that. The boys came to pick us up and one thing led to another and we never did get to the Beverly-Hilton. Well, Ann and I got the giggles at one point and we pretended to be very miffed with our dates. And at about twelve o’clock we said we were very tired and we asked the boys if they’d please take us home. In our anxiety to get out of the car and get upstairs so we could continue to have a good laugh, Ann-Margret mistakenly pointed to the wrong apartment house as the place where she lived. So we got out of the car, said goodnight to the boys, went into the building—which was an exact duplicate of the one where Ann- Margret lived—and we couldn’t for the life of us understand why her key wasn’t opening the door. Golly, we laughed so much that night our stomachs hurt. And about Ann and Burt—I’ll tell you this. She really wasn’t too impressed with him that first night they went out.”

But, a day or two later, Burt phoned again. Ann-Margret accepted.

And that night when they went out, things were quite different between them.

They went to a noisy little club just off the Strip. They sat and ate and watched a show for a while.

And, then, marriage

And then, the noise around them not mattering suddenly, she and Burt began to talk . . . about many things that night.

And one of the things they talked about was marriage.

“Has anyone ever proposed to you?” asked Burt, from way out left-field way.

“Oh yes—” Ann-Margret answered, honestly, simply.

“Fellows you’d gone out with for a long time?” Burt asked.

“No,” said Ann-Margret. “There’s nobody I’ve gone out with for that long. I mean, these were just fellows I was out with a few times and who thought, ‘Ah, this could be the girl for me.’ ”

“And what did you say to them?” Burt asked then. “How did you tell them no?”

“I said, ‘I’m sorry, but if you want to get married, I’m not the girl.’ ”

“Did any of them ever ask why?”

“Oh yes.”

“And then what did you say to them?”

“I explained first of all that while I liked them, I didn’t love them. I explained that I felt too young for marriage. I explained that I felt I had a few thing to do with my life before settling down. Primarily to work. To work for a few more years so that I could—well, fulfill myself. And to work hard enough and to make enough money so that I could give my parents things that years ago they never dreamed they would have. Things like a house, they’ve never owned one, never in all their lives. And, well, a few other things.”

“But,” said Burt, “you could continue to work if the right man came along, couldn’t you? And do all the things you wanted to do.”

Ann-Margret shrugged.

“Suppose,” Burt went on, “just suppose the right guy did come along—suddenly, very suddenly—then what would you do?” “I don’t know. I really don’t.”

“Well”—and he thought for a moment— “what would he be like. this right guy?” “He should be strong,” Ann-Margret answered, quickly. “Not muscles. I don’t mean that. He doesn’t have to lift a five- hundred-pound weight every morning in order for me to be impressed. But I mean strong inside him—here in the soul. I’ve always thought that the man should rule—do you know what I mean? I mean that there has to be some rhyme or reason to this society and that if more women felt their men should be strong. there just wouldn’t be so many men turning away from masculinity. It makes me so hurt when I hear some girls and women say, ‘Oh. I can wrap him right around my little finger.’ I think this is so wrong, I think it goes against a law of nature. Of course my father has said many times, ‘If it’s all right with your mother, it’s all right with me,’ but I’ve always known that my father has the last word in our house. And it’s been so right this way. There certainly couldn’t be a happier woman than my mother.”

“What else about this guy, Mr. Right, when he comes along?” Burt asked then.

“You’ll think this next thing is foolish,” Ann-Margret said.

“What’s that?”

“I don’t want him to be a slob. I want a man who will dress well. I want a man who thinks enough of himself to look good. For me. For himself. For everybody who meets him.”

“And?”

“And I want a man who won’t mind me singing all the time.”

“I don’t think there’s any problem there,” Burt said.

“I mean singing around the house,” Ann-Margret said. “I’m always singing. When I dress, when I help with the dusting, when I’m sitting shortening a skirt. Even when I try to cook—which is always pretty much of a disaster, I don’t mine telling you—unless you like cheese omelets. I really do make the best cheese omelets.”

“I’ll have to try one sometime,” Burt said, “—and I don’t even like cheese.” They both laughed.

Then: “And what else?”

“Well,” Ann-Margret said, “he’ll have to be very sentimental about things. Or at least understand my sentimentality. Like when it’s Christmas I want to be, not only with him, but with my folks and family, or his. It’s just that I think Christmas and other holidays are days when lots of people who love one another should be together.”

“And?”

“And a man with a nice sense of humor, of course. A man who can laugh at himself when need be.” She paused and sighed.

“And a man who won’t think it’s such a terrible thing to cry once in a while, if that’s what he feels like doing . . . an honest man, is what I really mean. Yes. A very honest man.”

There was a pause then.

“What are you thinking?” Burt asked, after a while.

Again Ann-Margret shrugged.

“Tell me . . . come on,” he said.

“It’s just that—” she began, “it’s just that . . . sometimes . . . sometimes I wonder when I will meet a man I can fully love. This, too, I know may sound foolish —but I have loved so many things about so many boys that sometimes I get a little bit confused. once, for instance, when I was appearing in Vegas, this boy I’d known in high school—he was a sailor now —he hitchhiked all the way from his base in San Diego just to see me. And when he finally showed up, he had so little time that he could only stay and talk to me for ten minutes. He couldn’t even stay to see the show. And so we talked a little . . . ‘hello, how are you, gee you look great, remember the old days,’ and so on. And before he left he reached into his pocket for a little bottle of perfume he’d brought for me. And he’d been traveling so much and so hard that the package was all squooshed and broken by now. And when he handed it to me, when I realized what he’d gone out of his way to do for me—I loved him so much for that. Even for only those ten minutes. And there have been other incidents like that, with other boys. And, well, it gets very confusing sometimes.”

She looked sad for a long moment, after she’d finished saying what she’d just said.

And then, Burt smiled at her, Ann-Margret found herself smiling back at him.

“You know, Ann-Margret,” he said. “I like you. I like you very, very much.”

And Ann-Margret said, “I like you, too.”

“They seemed to be so much in love soon after they met,” says a Hollywood friend. “that I wouldn’t have been surprised if they’d just gone off somewhere and eloped. For a few months they were inseparable. I’d always known Annie to be a happy girl —but this happy?—never. Everything was sweet and dizzy now. Everything was moonlight in June and long-stemmed roses and stuff. once Ann said to me, ‘I don’t care how many millions of people have fallen in love since time began, there has never been a love like mine and Burt’s.’

“When Burt proposed, Ann-Margret was on top of that topmost cloud up there.

“When Burt gave her the ring, same thing—only the cloud was even higher.

“But then things began to happen, and the engagement and the happiness were all very short-lived.

“The reason? Pressures. From all over.

“First of all, Annie’s parents didn’t approve of the marriage. And they told her so. They felt she was too young. Burt Sugarman was a divorced man.

“Then the studio had its say. Studios have a funny way of not liking it when young girl stars run off and get married. They invest a lot of money creating an image and in Annie’s case it was the image of a young and radiant girl who should— for a couple of years, at least—be everybody’s girl friend and nobody’s wife.

“There were other pressures, too from friends, some real and some would-be.

“They pointed out to Ann that she was Lutheran, that Burt was Jewish, and that this could make a difference later on. They pointed out that Annie was in show business—that kooky, ever-travelin’ business—while Burt was in finance—solid, conservative finance—and that never the twain of basic temperamental differences would meet.

“They pointed out this and that.

“The pressures continued coming, from all sides.

“And one night Annie told Burt that she was sorry, that she couldn’t marry him. She gave him back his ring. And that was that . . .”

“I know it sounds cold, what happened between Burt and myself, in some of the accounts you hear,” Ann-Margret says. “But the truth is that the decision was a very difficult and heartbreaking one to make—and it was made by me and me alone. It is true that my parents objected, but only because I was too young and they wanted me to wait for a year or so. The true reasons for our breakup are too personal for me to go into. I consider love a personal and sacred thing and I don’t think I shall ever talk much about it. “I have just one fear now. And that is that I hope that if there are some people who like certain things about me, that I will never change. Or disappoint them. Or let them down. . . . Never. Ever.”

“Ann-Margret change?” asks Dr. Peterman, of New Trier High. “I don’t think so. She’s extremely loyal, to her family, to me, to just about anyone who ever knew her. Last time she was in Chicago, for instance, she gave me a call. I’m only in town a few hours and I can’t get up to school this time,’ she said, ‘but why don’t you come on downtown, Doc, and we can have dinner together?’ Here’s a girl who never forgets, a girl who never lets go of a good friendship or what she considers a valid obligation. My only worry is that she’s going to build up so many of these things that she won’t be able to handle them all in time.”

Says Joannie Stremmel: “Ann-Margret is a true friend and she’ll always be the same. She’d go out of her way, to any extreme, to make you happy. I remember last year I went out to see her in California. I was there for a week and it couldn’t have been nicer. Ann-Margret, it happened, was on the go from A.M. to P.M. But this didn’t mean that she ignored me. Where somebody else would have said, ‘Gee, Joannie, I’m so busy, would you mind going off to a movie this afternoon?’ Ann-Margret made sure that I went with her, wherever she had to go. She took me to the studio and introduced me to all the important people there. She had an appointment with her agent—and there was I, right there along with her. Lots of these places, I’m sure she could have done without me. But never once did she give me the feeling that she was leaving me out in the cold. No, Ann-Margret never forgets you. And I’m very flattered to be her friend. Not because she’s a movie star, but because she’s the person she is.”

Says Holly Salvano: “She’s the most loyal person I’ve ever known. I, too, went out to visit her in Hollywood recently and she made sure that I was always included in everything. There has never been a Christmas or a birthday that she’s forgotten. She has a heart of gold. She’s the best friend I’ve ever had—and ever will have.”

Says Sharon Lauver: ‘I’m sure that if I’d ever become a movie star it would have done all sorts of awful things to me. I know I would have changed. I just know it . . . But not Ann-Margret. To give you an example—and this is something I shall never forget, not for as long as I live—when we were kids together, we always used to talk about our dreams, you know? And mine was to grow up and meet a fellow I loved and to get married. And Ann always used to say to me, ‘When you do get married, Sharon, I’d like more than anything else to be your maid of honor.’ Well, a few months ago I became engaged. I phoned Ann in California to tell her the good news. And before I got more than two sentences out she interrupted and asked, ‘Sharon, unless you have another girl in mind, may I be your maid of honor, just the way we used to talk about it when we were kids?’ My wedding took place in Summit, New Jersey, where my family now lives. That’s quite a long way from California. I knew how busy Ann-Margret was, how it meant quite a bit for her to fly East for that one day. But she did it. For me. For our friendship. And, well, what more can I possibly say about her?”

Says Uncle Roy Weselius: “She’s still the sweet, good girl she always was, and will always be. She came to Chicago not long ago and she invited me and her Aunt Gerda to her hotel one night. She was working and she said she was sorry we couldn’t spend more time together—but at least, she said, we would all have dinner together. So my wife and I went. And when we got there I said, ‘Ann-Margret, I’m going to take you to dinner over at the Sherman House.’ And Ann-Margret said, ‘Oh no you’re not. We’re going to eat right here in this hotel.’ So there we were a little while later, down in the dining room of the Hotel Ambassador-East—the world-famous Pump Room. And I’m sitting there like a monkey thinking, ‘Hell, no, I’m not going to let my niece pay for me. When the check comes, I’m going to grab it and I’ll do the paying.’ But the check never came. Ann-Margret had taken care of all this beforetime. And I was so embarrassed I finally said to her, ‘Look, I insist that I pay that check.’ And she said to us, ‘Uncle Roy . . . Aunt Gerda . . . you’ve both done so much for me all my life, now it’s about time I did a little something for you.’

“Ann-Margret pushed herself forward in life. She worked hard. And Fm proud of her and the way she now presents herself. She has not allowed herself to be swept away by the temptation of drinking and smoking. She has never allowed her head to be turned by all this success.

“Yes, it’s a Cinderella story to begin with—but if diamonds were going to be paid for effort and for niceness, Ann-Margret deserves them. All the diamonds she can get . . .”

—ED DEBLASIO

Ann-Margret’s in “Bye Bye Birdie,” Col.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1963

AUDIO BOOK