Ann-Margret’s Life Story!

PART I

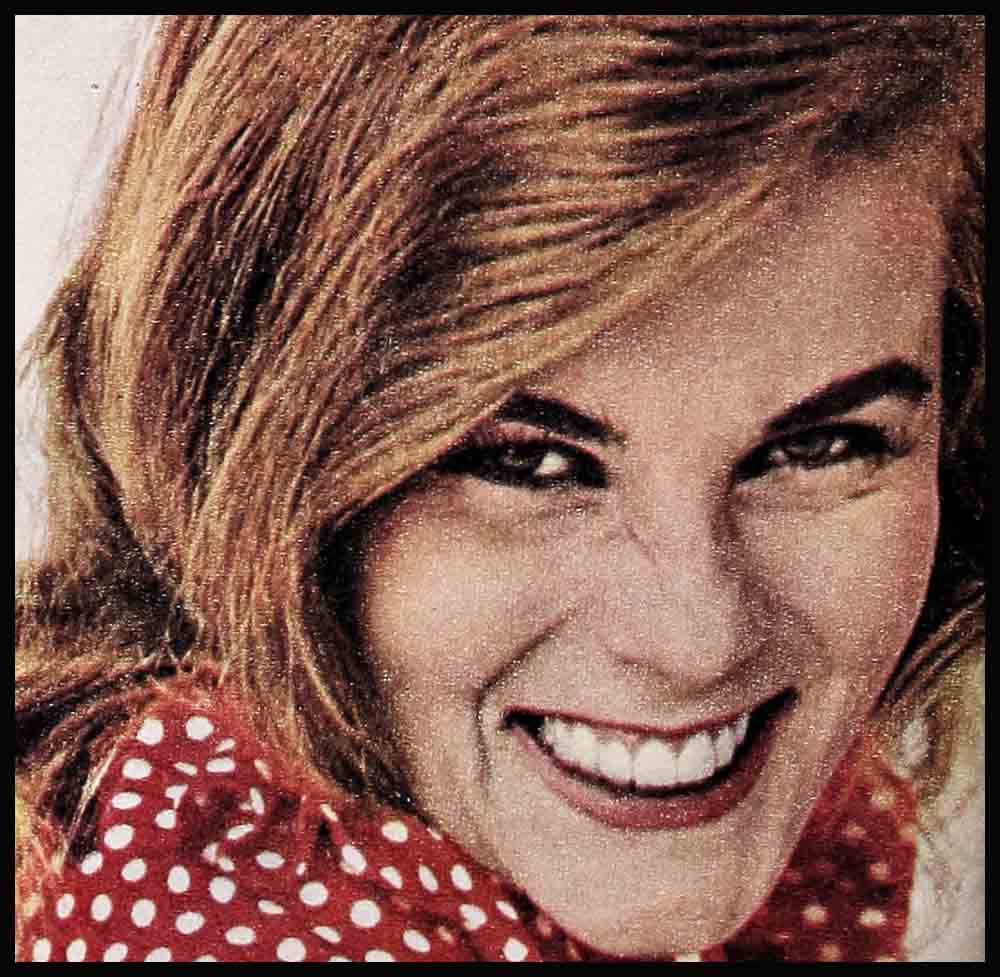

It seems to be an old Hollywood rule that when you’re new in town but obviously on your way to the Big Time, there are people around who just will not like you. Who will easily and happily hate you, as a matter of fact. Ann-Margret Olson—twenty-one, five-feet-four, green-eyed, with that long silken brown hair of hers, pretty as they come, more talented than they usually come, definitely headed for the Big Time—is no exception to the rule.

>

The story goes that early last year, when she showed up at a major studio for filming a major new musical, she was welcomed by one and all as a cute young thing who’d be a very nice addition to the picture. Newspaper and magazine articles about her indicated that she was “sweet and friendly.” Comedian George Burns, who’d been her discoverer, remarked that “this kid is so nice and sweet she cries on New Year’s Eve!” and that seemed to make her inoffensive enough. She was, in short, just another ingenue who would smile pretty for the camera, recite the script’s most innocuous lines, sing a little and dance a little—and then get herself lost in the shuffle.

But as the filming of the picture got under way and it became clear that the ingenue was a star in every sense of the word—when the producer began to dish out orders that her part be expanded—then expanded more—and then some—well, the attitude toward Ann-Margret changed. Fast. And a rather insidious we’ll-show-her campaign got under way.

One of the people connected with the picture confided to anyone who’d listen “That little Annie is cold as a Canadian fish—and a phony.” And a friend of the gossip told us, “That Miss Annie-M, she’s a troublemaker. She stands there and acts so goody-good. And then behind your back she talks about you till she’s hoarse.” Word also began to get around that Ann-Margret was excessively boy-mad (you’d have thought she dates everyone from Frankie Avalon to Dr. Zorba in a week’s time, if you’d heard all we heard); excessively vain (“She’ll never talk about her short-hair days. I guess you’re supposed to think she was born on Lady Godiva’s horse or something!”); excessively publicity-hungry (her dates with Eddie Fisher are often cited as a good example along that line).

Word got around so much—and so quickly—that we decided to do some inquiring. And what did it all add up to, this gossip? Nothing, we learned. Nothing but a lot of nonsense, really. Because jealousy is a commodity which rears its unpretty head in Hollywood just like anyplace else—like, say, a certain school—a high school in Winnetka, Illinois.

AUDIO BOOK

But we’re jumping our story now. We,ll get back to all this a little later on. For now Ann-Margret asked, as I started to do her life story, “Shall I start at the beginning? Yes? Good. It is easier that way. Well, I was born in Sweden, in Stockholm. But I don’t remember any of that place, since we moved away when I was only a year old. We went to a town in the very northernmost part of Sweden. It had tall fir trees and it was very cold in winter. It was small—they used to say that the population was two hundred, and that included the horses and cows. It had a very lovely and musical name, I thought. It was called Valsjobyn . . .”

Valsjobyn was a happy town, and a special paradise for a little girl. It was so far north that it was practically always covered with snow, so she could ski and belly-whop and ride a makeshift toboggan to her heart’s content. And her grandmother owned the only bake-shop in town and this made Ann-Margret a particularly big hit with the little boys, to whom she was forever passing out cookies and pastries in return for small favors. Like, “Please may I come sliding down the big hill with you today?”

Ann-Margret’s memories of life in Valsjobyn are naturally vague (she was only five-and-a-half when she left). But there are a few of the memories that stand out. And they are well remembered by her. . . .

There is, never to be forgotten, the memory of that Christmas Eve when she was two-and-a-half. And her Uncle Calle had a party at his house. With lots of relatives and friends there. And a table laden with smorgasbord, prepared by all the women of the family—a million and one delights, it so seemed, for the eye to linger over and the tongue to savor. There was dancing later, with music from the big brown radio in the corner, music by orchestras from Stockholm and Malmo and Gothenburg. And then, as if by magic, more music—real music this time—from a box which Uncle Calle held in his arms and pressed with his fingers and swayed with—a box that they called an accordion. From which came sweet sounds. And to which sweet music the people continued to dance now. And sing. All together. Wonderful Swedish songs. With Ann-Margret, sitting there on the sidelines with the other children, watching and listening. Until something very strange seemed to begin to happen to her; a strange feeling which suddenly overtook her. And she found herself rising from her chair, slowly, after a while. And, after a while, she began to join in the dancing, then the singing. And she remembers Uncle Calle’s voice calling out to the others, a few minutes after she had begun. “Look at my niece. See how well she moves. Like Pavlova. And how she sings. Like Jenny Lind. See, see how well she performs.”

“Hej!” she remembers someone else calling out then. “Stop. Stop everyone. Give the child some room. Let her sing and dance alone.”

“Hej, hej, hej!” she remembers the others calling, then shouting, as they stood around her in a big circle and clapped their hands together in time with her steps and her song.

“Hej!”—and the sound remains in her head today, the sound of the very first applause she ever received, that Christmas Eve when she was only two-and-a- half . . .

There is, too, the awesome memory of the first time she ever heard of the glamorous entertainment form which she would someday be involved in—the movies.

She was nearly four years old now, and talking with her mother about Stockholm.

“And how else is it different from Valsjobyn, Mamma?” she asked that day, as they talked. “You have told me about the palace where the king and his family live, and about the park where they keep the animals, and about the tall buildings so much taller than we have here. Is there anything else different about Stockholm, Mamma?”

“Well,” answered her mother, “let me | see. Let me think.” Then: “Ah, yes. The cinema, of course. There is much cinema in Stockholm. Something we most certainly don’t have here in Valsjobyn.”

“Cinema, Mamma? What is that?” Ann-Margret asked.

And Anna Olson described the big dark theaters with their hundreds of seats where people went to see a play on a huge screen, a play about love or adventure or music, about things to make you laugh and to make you cry.

“How wonderful it sounds,” said Ann-Margret, wide-eyed with delight. “Do you think that one day, Mamma, I shall ever be able to go to a cinema?”

To which her mother answered jokingly, “You keep singing and dancing as much as you do, and I think that perhaps you will end up being on the screen rather than in front of it!”

There is. of course, the memory of the first boy Ann-Margret ever fell in love with. She was all of five by now. And he came one day from a region of Sweden even further north than Valsjobyn. He was tall and blond and very strong looking. He must have been seven years old—or maybe even eight. He came to Valsjobyn with his father, a dealer in reindeer hides, for only a few days. Ann-Margret first saw him when he and his father checked into the town’s single hotel. She smiled at him. He smiled at her. For the next few days everytime they saw one another they smiled. And then, suddenly, the boy was about to leave—his father having sold enough reindeer hides for them to be off to another town where they would do some more business.

“Ann-Margret, child! What are you so flushed-looking about?” her grandmother asked that morning as the girl rushed into the bakeshop.

“Grandma, oh Grandma, may I bake a cake—please?” Ann-Margret asked. “Bake a cake? A little thing like you?” “Hmmmmm,” her grandmother hmmmmmed, not understanding what this was all about—except that it was obviously important. “Well . . . all right. But I must help.” A little while later, the special cake was baked . . . a beautiful little thing.

Then she clutched the package and ran to the hotel down the Street.

She got there just in time, as it turned out—just as the boy and his father were about to leave.

“God dag,” Ann-Margret said to the boy. “Hello.”

“God dag,” he said back to her.

She handed him the cake.

“Adjö,” Ann-Margret then said to him. “Goodbye.”

“Adjö,” said the boy.

They stared at one another.

“Come!” the boy’s father hollered suddenly, gruffly, “let’s be off from here.”

And so the boy did as he was told, and he was gone.

And so had Ann-Margret’s first romance begun and ended. . . .

Of all the memories of those early days back in Valsjobyn, however, the ones Ann-Margret remembers most concern the letters which she and her mother received from her father, Gustave Olson.

They came, from America, every few weeks.

They were long letters, filled with love and loneliness and hope for the future.

They would be read aloud to Ann-Margret by her mother, the moment they arrived . . . then read again a few times during the day . . . and, finally, read once more when the little girl got into bed at night, and as she dozed off to sleep.

Usually, just before the letters were read, Ann-Margret would ask her mother: “Where is my Poppa?”

To which her mother would answer: “In a place called Chicago. In the nation of America.”

“And why did he go away from us, Mamma?”

“To find work, as an electrician, to make a better life for us.”

“And why did he not come back, or send for us?”

“Because of a war that now rages through the world, Ann-Margret. Because it is dangerous for us to even try to cross the ocean during a time like this.”

“Is he young like you, Mamma?”

“He is eighteen years older than I.” “Such an old man? Why did you marry him, Mamma?”

“Because I loved him. Because he is fine and good. And because eighteen years—no years—make that much difference when there is love.”

And she remembers—early in 1946, at long last—this letter. A letter from Poppa.

“Enclosed you will find two steamship tickets, one for you, my Anna, and one for my little Ann-Margret. Also papers that will facilitate your entry into these beautiful United States of America. I know that it will be difficult for you both to leave our beloved Sweden, just as it was difficult for me. But, believe me, this is a great and wonderful country I bring you to, where the possibilities for a successful future are limitless. Our home will be in Fox Lake, what is called a “suburb” of Chicago, near your sisters Gerda and Mina and their husbands Roy and Charlie. We will have a nice life here, God willing.”

And thus did Anna and Ann-Margret Olson leave Valsjobyn . . . for America.

“The ship that carried us across the ocean was white,” Ann-Margret remembers. The journey lasted nine days.

“And on the morning of the tenth day the liner docked in New York.

“My father, of course, had come to welcome us. He stood on the pier, waiting for us to disembark.

“When we finally did, he embraced and kissed my mother. first. over and over and over again. Then he knelt to kiss me.

“But first I had a few questions to ask.

“ ‘Are you my Poppa?’

“ ‘Yes,’ he said.

“ ‘Mamma,’ I asked, looking up at her. ‘He is my Poppa? You’re sure? There’s no mistake?’

“ ‘Yes, Ann-Margret. Of course he’s your Poppa. But why do you even ask such a thing?’

“ ‘Because,’ I said, ‘I’ve saved so much love for my real Poppa all these years that I don’t want to go wasting one little bit of it on anybody else.’

“At which point, my father broke out into a loud laugh.

“And he grabbed me. And I grabbed him. And then the real hugging began . . .”

“The first time I saw Ann-Margret,” says her aunt, Mrs. Mina Erickson of Fox Lake, “was the day she arrived in Chicago. All of the family went to the station in the city to pick up her and her mother. And what a picture she was, this pretty little girl. She wore, I remember, a white fur coat made of baby goat skin. And a hat to match. And little white boots. She looked like the prettiest little polar bear you have ever seen.”

Ann-Margret’s uncle, Roy Weselius, who drove the Olsons back to Fox Lake that day, remembers: “She was very small. And naturally, she could not speak a word of English. She was so very excited in the car that day, asking all sorts of questions about the places we passed. We stopped at our house first, the place where my wife Gerda and I live. And right away, from that first day, I could see that little Ann-Margret had talent. For within no time at all, after we’d all had our coffee and cake, there she was, up on the table, singing old Swedish songs for us, along with her mother. I happen to be in the hobby shop business now. But back then I was a dance instructor, too, and I knew quite a bit about show business. And I could see back then, when she was only five-and-a-half, that here was a girl who had what it took—that singing and dancing was going to be her life.”

Following the coffee and songs at Uncle Roy’s and Aunt Gerda’s, Ann-Margret was taken to her first new home in America—an apartment actually, the second floor of a two-story house on Lake Avenue and directly next door to where her aunt and uncle, Mina and Charlie Erickson, and their daughter, Anne, lived.

Remembers Anne (now married and living in East Orange, New Jersey) : “I was twelve at the time and an only child and I was terribly excited that a little cousin was coming from Sweden and was going to live right next door to us. But when she arrived, and as I got to know her, i she became more like a little sister to me. She was so adorable, to begin with. She was such a kind little girl. Everything about her, in fact, was so sweet and nice that I just loved her from the very start. And she was so appreciative of anything you’d do for her. I remember how for months before she came, her father had spent so much time preparing her little room—with a record player, and little stuffed toys and all kinds of frilly little things. And when Ann-Margret saw the room that day, what he’d done for her, she just laughed and laughed so happily that you’d have thought she’d burst with excitement. As far as I was concerned, well, there wasn’t enough I could do for this little girl. Not as a favor, I don’t mean it that way. But just to be with her is what I mean.

“I think the times I remember most were when we’d be in her house and she’d go to her mother’s closet and dress up in Aunt Anna’s clothes—long dress, high heels, big hat—and sing and dance for me. And the funny thing was that every once in a while I would think to myself, ‘Someday, years from now. I’ll be in a theater somewhere and the lights will go down and Ann-Margret will come out and sing, not only for me, but for thousands and thousands of other people.’ And after she sang, of course, I would always applaud. And in my mind. somewhere in the back of it. I could hear the applause of those other thousands—even though she was not yet six at the time—even though they were only little Swedish songs she sang then.”

People in Fox Lake who remember her—and there are many—recall that she was “rather quiet,” “reserved,” “extremely polite” and “extremely close to her parents.”

A former grade school teacher of Ann-Margret’s remembers this encounter with the girl one afternoon:

“She was just about to leave school and I called her over to tell her how well her English was coming along and how she must be studying it at home all the time.

“ ‘Oh, yes,’ said Ann-Margret, ‘I study it much. That is, when I am not taking my toe-dancing lessons with Miss Young.’ “ ‘Toe dancing lessons,’ I said. ‘Now isn’t that wonderful.’

“ ‘Not only that,’ said Ann-Margret to me, ‘but soon I will begin my piano lessons with Mr. Hallin.’

“Of course, I knew it was none of my business, but at this point I couldn’t help asking: ‘Isn’t this all rather expensive for your parents, Ann-Margret? These are fine teachers they’ve chosen for you. And they don’t come free.’ ”

“To which Ann-Margret answered: ‘You are right. It doesn’t come free. To help pay for the lessons my mother does cleaning work two or three times a week. And my father works overtime at his job. But it is worth it, they say. They say that I have a good feeling for music in me. That I was born with this feeling in me. And that now it is up to all of us to cul-ti-vate this feeling.’ ”

Says a Fox Lake neighbor of the Olsons: “I don’t think there’s any hiding the fact that Ann-Margret’s parents were pretty dam poor. But came the time when she had to give a recital at Miss Young’s. and Ann-Margret got the best pair of ballet slippers available. Her parents saw to that. And came the time she needed a special costume or something, and there was Mrs. Olson sitting up till all hours of the night. sewing the dress together and then putting on the sequins, one at a time, dozens, hundreds of them, sequin after sequin.”

When Ann-Margret was eleven—and the sequin count had undoubtedly reached the thousand-mark—her mother and father decided that it was time for them to leave Fox Lake and move on to another Chicago suburb named Wilmette.

Their reason was a very simple one.

They had heard about a high school called New Trier in Winnetka, just this side of Wilmette. They had heard that academically it was the finest high school in the State of Illinois, and that—equally important—it boasted a music department that was probably second to none in the entire country.

Ann-Margret, it happened, was more than a little loath to leave Fox Lake at first.

“But Mamma . . . Poppa . . . we have hills here and we can ski in the winter,” she said, in one of her rare rebellions. “And Auntie Gerda and Uncle Charlie and everybody are here, and I won’t have any more friends.”

To which her parents replied, “The hills will remain, Ann-Margret. We can always come in the winter to ski. We will always be able to see everybody here. As for friends, believe us, you will make new ones. Besides, we are only going a short distance away.”

And so a couple of months later the Olsons left Fox Lake for the town and the school that would make all the difference to a young girl’s life, and her future . . .

“It’s funny,” says Ann-Margret today, “how like all children I was so afraid to leave the place I knew so well. But what my mother and father had told me turned out to be true. Of course. we went back to Fox Lake to ski. Of course, we continued to see our family. And, of course, I made new friends. . . . The very best friends I ever had were in Wilmette, in fact. There are three especially. and their names are Joannie Stremmel, Holly Salvano and Sharon Lauver. You should talk to them before you write your story about me. I’m sure they’ll tell you things about me I’ve even forgotten—” (smiling) “or maybe I will wish I had forgotten. . . .”

We talked first to Sharon Lauver, now a student at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, who told us:

“I was the first of the three to meet Ann-Margret. My assignment at school was to show her around, to introduce her to some of the other boys and girls, stuff like that. We became good friends right away, and we were forever at one another’s house. I’d always go to Ann- Margret’s house in the morning, to pick her up for school, and she was proverbially late. She’d gulp down her breakfast so hard I thought she was going to get an awful stomach ache. Then, after school, we’d go to my house. Usually, my mother had made a big batch of divinity during the day—that’s a certain kind of fudge—and Ann-Margret liked it so much she’d end up gulping quite a bit. She was a wonderful girl. You could talk to Ann-Margret and you always had the feeling that she was listening to you—something a lot of people don’t seem to do. And the more I knew her, the more I loved her. All through high school—and later—we were the very best of friends. You could tell her the deepest and darkest secrets, and she would never, never tell anyone else. That was only one of the reasons for our friendship. Was she popular with the other kids? Yes. With lots of them. Lots. Except that something very strange happened at the beginning of our senior year, something I’ll never forget. Ann-Margret had been a cheerleader for three years before that, certainly the best and most conscientious the school had ever had. We, her good friends, all assumed that she would be chosen head cheerleader during her last year. But she wasn’t. A lot of the kids suddenly thought that she’d had too much. They were jealous of her, I think. Pretty jealous. And though Ann never indicated any disappointment over this, I think she was.”

We talked next to Joannie Stremmel, now a business school student in Wilmette, who told us:

“I guess I first saw Ann-Margret when we both were twelve. It was at a square dance given by the Boy Scouts. The first thing I noticed was her long hair. The second thing was that she really knew how to square dance. And the third was that the boys, all of them, took to her like a magnet. I know how jealous some of the girls in that room were that night. It must have been a year or so later when I really got to know Ann-Margret, however, and got to realize that she was one of the dearest and most wonderful people ever. What was so wonderful about her? Well, you could trust her with confidences, for instance—and that’s pretty rare. In other words, she was a true friend, and there aren’t too many of those left. A lot of people don’t realize this about Ann-Margret, but she’s a very sensitive girl. It would just kill her, I mean, for her to think she’s hurt somebody. I remember once, in high school—I’m a kind of funny person sometimes, too—and this one day I decided I didn’t like something she’d said or done and that I wasn’t going to talk to her anymore. Truthfully, I don’t even remember what it was that was bothering me. all I know is that I was bothered by something, and that I was going to let her know it. So we’d pass by one another in the hallway at school and I’d just keep walking. The same thing in the Street. You know the kind of thing. Until finally, on the third day, it was just tearing Ann-Margret’s heart out and that afternoon at 3:30, after school, she went to my house and she said to my mother, ‘Something’s wrong between Joannie and me, Mrs. Stremmel, and I just don’t know what it is.’ She burst into tears then. She was still crying a few minutes later when I walked into the house. Before I had a chance to say any thing, she said to me, ‘Joannie, I don’t know what I’ve done that’s so wrong, but whatever it is, I’m so sorry.’ And she threw her arms around me. And I felt so terrible. I learned something about Ann-Margret that day. I learned that for her to feel that she had unintentionally hurt somebody else was the kind of thing that could give her the severest kind of pain. And, well, I felt like a heel that day.”

We spoke, last, to Holly Salvano, now a librarian in Wilmette, who told us:

“I miss Ann-Margret. Because, very frankly, I miss the wonderful ball we used to have together. One summer, I remember, Ann-Margret’s father was on vacation and he invited me to go along with the family to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, for a little while. We stayed at the Gateway Motel—well, the Olsons, Ann, me and twenty-eight college boys from Muskegon College stayed at that motel. Those boys were really something. They were always out of money and Ann-Margret and I used to feed them our stale cookies. For this they were appreciative. But they could never seem to get enough money together to ask us for a date. Strangely enough, we never double dated while in high school. I guess we just liked boys who didn’t know one another. Anyway, Ann-Margret dated more than I did. And I’d like to say that the people who say she dates so much and so indiscriminately don’t know a very important thing about her—they don’t know that she never thought anyone not good enough for her to go out with. I mean, she found a little bit about everybody to to like. So where another girl might turn down a date because ‘I don’t like his eyes’ or ‘He never shines his shoes’ or ‘He only takes me to a movie’—Ann-Margret would think ‘He’s very polite’ or ‘He has a nice sense of humor’ or, if he didn’t have a nice sense of humor, ‘Well, he certainly tries hard enough, and what more can you ask?’ And so she’d go out quite a bit here in Wilmette, just as she does now in Hollywood. And the reason for this is that number one: she likes people, and number two: I think it would break her heart to have to turn anybody down. You know, it peeves me a little to see some of the things some people write about her nowadays. I know that if you’re famous you can expect just about anything. But, still, it peeves me. Just as it used to back in high school, back when so many girls were so jealous of Ann-Margret they couldn’t see straight. Oh yes, there were more kids who were jealous of her than those who praised her. It’s ironic how some of the same girls who used to make all kinds of snide remarks about Ann-Margret —her long hair, her singing, her dancing, the fact that she was cheerleader for three years, the fact that she was so popular with the boys—now will come up to me and say, ‘Gee, Holly, I saw Ann-Margret’s movie the other day and she was great. And she’s still wearing her hair that lovely way!”’

“There were a few people who I guess, were jealous,” says Ann-Margret, dismissing that subject with those few words. “But more important to me were the people who were my friends—girls like Holly and Joannie and Sharon. And the teachers who helped me. There were so many. I couldn’t begin to list them all for you. But I guess the one I remember most is Dr. Peterman, head of the music department at Trier. He believed so much in me. He was the one who told me my career might well be in movies one day. Of course, I hate to say it, but there was a time I resented him. It was my freshman year. I tried out for the role of Ado Annie in “Oklahoma.” And Dr. Peterman turned me down saying I wasn’t right for the part. I was crushed. I really thought he had something against me. When I got to know the show, however, I realized that he’d been right. . . .”

“Of course I was right,” Dr. William Peterman told us, smiling. “I could see from the beginning that Ann-Margret had great potential, was loaded with talent. But she had to learn early that while she could do much, she couldn’t expect to do everything.

“She was thirteen the first time I met her. It was a very impressive meeting. I was sitting in my office the first or second day of school, I remember, and a few of the kids came up to me and said, ‘Hey, Doc, do you want to hear somebody who can really sing?’

“Now, New Trier is a large school—I think we had nearly eight-hundred kids in the freshman class that year—so I don’t have time to see everybody. But this day, for some reason, I managed to make an exception.

“They took me to this room, I remember.

“I saw her standing there—pretty girl, long hair, bright and very intelligent eyes.

“I said to her, ‘Okay—sing.’

“She said, ‘I wish there were somebody here who would accompany me on the piano.’

“I said, ‘Forget the piano, just sing.’

“And she said—I’ll never forget it—‘Fine. I don’t need a piano anyway.’ She didn’t say it in a brassy tone of voice. She said it as though she really meant it. And when she started singing, believe me, Ann-Margret Olson didn’t need a piano.

“I coached her as much as I could during the next four years, as did others in my department and in the drama department. She learned a lot here, too—despite her innate talent. I hear that she’s considered one of the most professional young people in Hollywood today. Well, she should be—because she got good training here at New Trier. She learned, first of all, that show business is not all glamour. She knows you’ve got to study to get anyplace in it. She knows her left foot from her right, and upstage and downstage, and what a light hoard is.

“I told her she’d be in movies one day? Yes, that’s true. It was after she did ‘Plain and Fancy’ for us here. She was excellent in it, truly excellent. Afterwards I had a talk with her and I said, ‘Look, gal, I predict big things for you. The movies, probably.’

“She began to laugh.

“ ‘Don’t think I’m just being complimentary,’ I said. ‘You’re photogenic. You can act and you can sing and you dance well. If the break comes, I predict just that—Hollywood.’

“And she said to me, ‘Impossible, Doc. Just impossible.’

“Well, a year-and-a-half later she sent me a telegram. ‘You were right,’ she wired me, ‘. . . I made it.’ ”

—ED DE BLASIO

(To be concluded next month)

Ann-Margret’s in Col.’s “Bye Bye Birdie.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1963

AUDIO BOOK