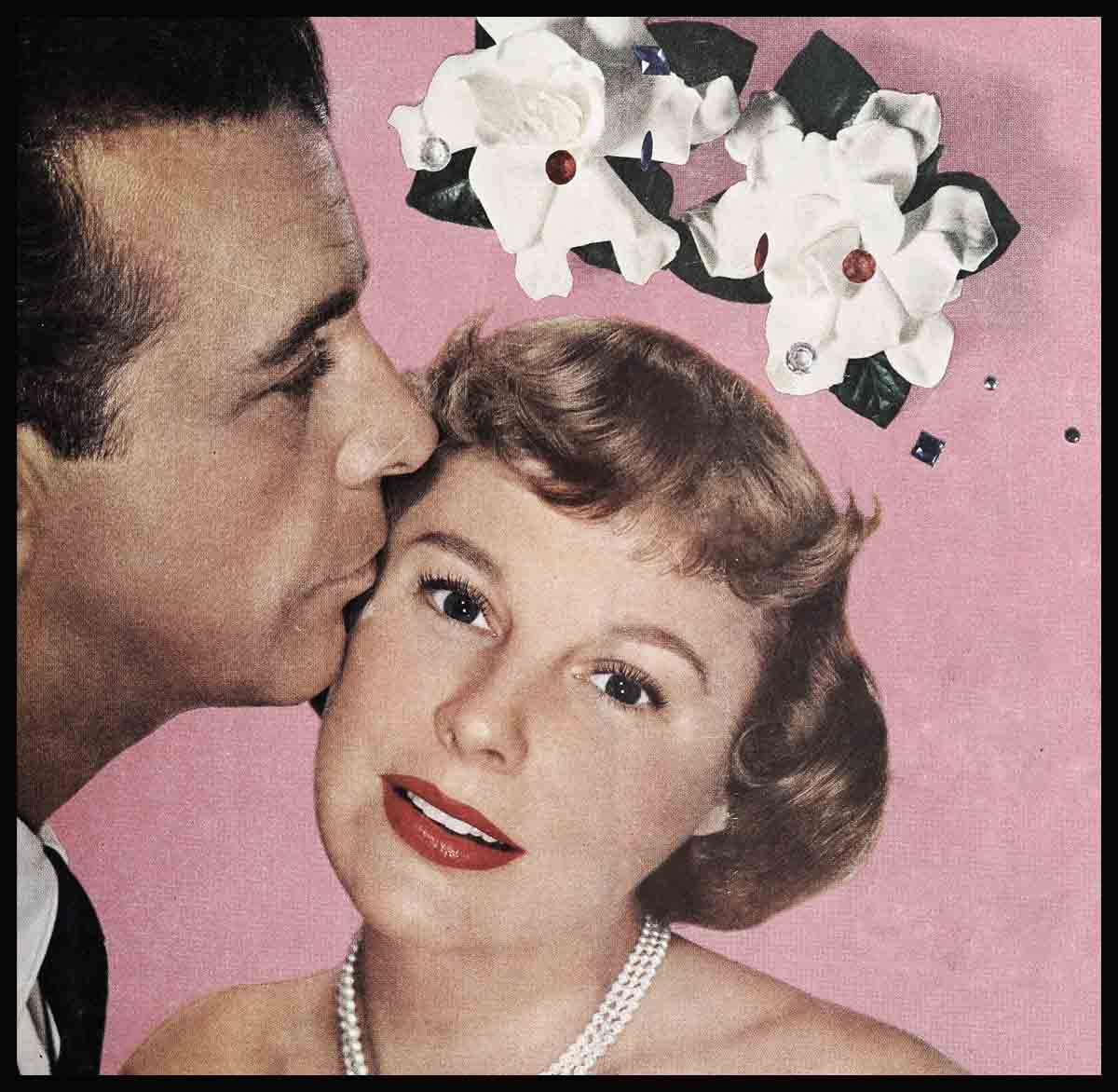

The Best Year Of Their Lives—June Allyson & Dick Powell

In the darkness of a downtown Los Angeles theater, June Allyson held onto her husband’s tweeded arm excitedly. It was that magic moment after the flash, “Major Studio Feature Preview,” when the crowds wait, hushed and expectant, to discover the star identities of their extra entree. At the words “June Allyson and Dick Powell . . .” they fairly screamed their applause.

“They like us!” said June happily.

Behind them, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer executives who, in co-starring them, had stepped in where angels, particularly those of the box office, have feared to tread, began to breathe again. Only too well did they remember the past, when teaming husbands and wives had speiled mutual oblivion.

But the public love the Powells’ camera-derie. And out of that first preview applause was born Hollywood’s gayest new star team. After “The Reformer and the Redhead,” sure that starring with her husband only enhances June’s romantic appeal, M-G-M lost no time in co-starring them again in “Right Cross.”

“How lucky can a girl be?” June asks. This is the “happily-ever-after” of a fabulous seven-year-cycle for a small-town girl, born of poverty, whose daydreams and determination led her into a motion picture career. A girl who’d stood on the very same sound stage where “The Reformer and the Redhead” was made, watching wistfully in the background as cameras turned on the big musical number of Dick Powell’s. Hers was only a bit in “Meet the People,” but she met the man she was to marry two years later, and hoped, even then, someday to work with him. This was the dream, the wish her heart had made. She married him; they have a beautiful two-year-old adopted daughter, Pamela; another arrival is expected any day; and, at long last, she is co-starring with Dick. For June, anything else that happens is velvet.

Actually, that happy combination of June and Dick working together is more like pink champagne. A laugh a minute, an atmosphere effervescent with gaiety.

“It’s so wonderful working with your husband,” says June dreamily. “It’s so relaxing. You’re so much closer to him.”

“An advantage, too, working with your wife,” Dick says teasingly. “You can yell at her and you can’t at strange girls. Not that I wouldn’t love working with June anyway,” he adds. “She’s fun.”

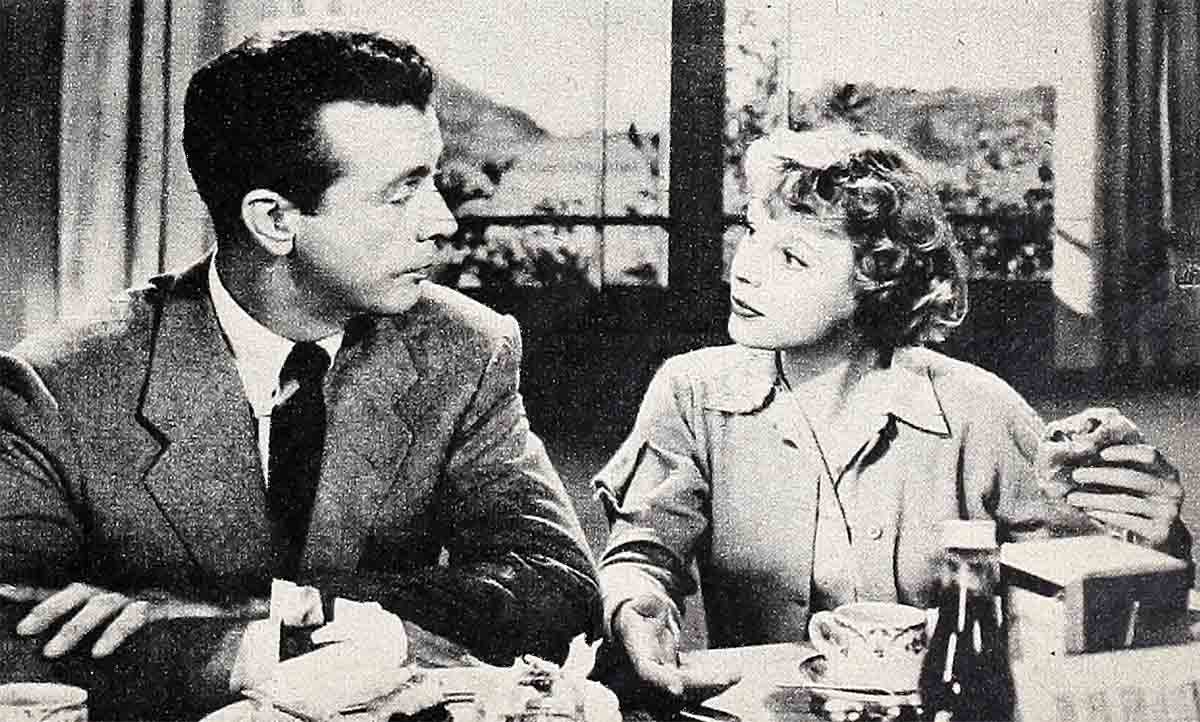

They had once hoped to co-star in that tender love story, “Mrs. Mike.” Their initial starrer, however, turned out to be a hilarious comedy and their love scenes were played with live lions stalking them.

It was a picnic for the Powells from that first morning when Dick walked on the sound stage to find June, who’d preceded him, had rigged up an oversized star on the front of her portable abode with the sign, “No. 1 Dressing Room,” billboarded on it, and on Dick’s, in elite type, the words “supporting cast.” June’s husky laugh had ended in a sentimental tear when she found his flowers in her dressing room.

It was agreed between them that neither was to tell the other how to read a line. Not one. Both memorize their lines by studying them aloud, so they repaired to separate rooms. Dick to the den, June to her bedroom, meeting later in the dining room to rehearse.

Dick began his line and June interrupted with, “Sweetheart, you’re very good. I hope you won’t misunderstand me, that was fine but don’t you think this line would be a little funnier if you’d. . . .”

“No!” said Dick emphatically.

“Well, I do!” she said.

“Then we got into a big hassle,” she grins now, recalling it, “that wound up with me admitting Richard was right. A fairly safe assumption, since he always is.

“I know I had no right to suggest,” she apologized. To be met with Dick’s weakening, “That’s all right, doll. You may be right. Maybe I should read it more. . . .”

“That’s ridiculous!” objected June. “You know you’re right.” Then they were in another small hassle again. After that first night of homework they reagreed to abide by their agreement.

They arose together every 7:15, rode to work together, “Well, most of the way,” June amends. “I would leave before Richard did, I’d be three blocks down the street walking and he’d pick me up. I like to walk anyway and he would always be on the telephone. Even at 7:30 he talks on the phone. Someday I’m going to tear that phone out. But then he’d be living in the corner pay station, so. . . .”

There was scant danger of them stealing scenes from each other in “The Reformer and the Redhead,” in the presence of so many animals, but neither tried. “I was always trying to keep her face in the camera and she was always trying to keep mine in,” grins Dick.

“I always wanted the scene to fade out on Richard on his line. And he was always fading it out on mine saying, ‘No, it doesn’t make sense, June.’ ” Then, too, he refused to take the top billing his contract always calls for, insisting June’s name must go first on their pictures. “That’s the only real hassle we’ve had, we both want second billing,” she says. “And he should have the star billing but he won’t, with me. Most uncooperative,’ she teases, then sighs, “but he’s such a smart man. I learned so much working with him, he almost gave me an inferiority complex.”

Dick isn’t prompted by husbandly devotion but by some nineteen years of wisdom and experience in the business when he speaks of his wife’s histrionic ability saying, “June’s a fine actress. I don’t think she’s even scratched the surface yet. I have yet to see anyone with as much talent. She hasn’t hit her part yet, but someday her part will come along. They do for everyone. If they get a good script of ‘Forever,’ June would be fine for it. Or ‘Sister Carrie,’ she could do that, too.” He agrees enthusiastically with the producer who once said, “If June could look any age, there isn’t a part anywhere she couldn’t play.”

“He loves me. He thinks anything I do is good,” remarks June, reentering at this point. “He cried all the way through ‘Little Women.’ It seemed so funny, a big man like Richard crying.”

“I wasn’t crying at you,” he interposes drily. “I was crying at the picture. Everybody cries at ‘Little Women.’ ”

When he made with l’amour with a vivacious blonde charmer, Marilyn Monroe, in “Right Cross,” his wife insists she was highly objective about the whole thing. “I just took a front seat right by the cameras, gave him a sweet, understanding glare and said, ‘Honey, you go right ahead and make this romantic. I don’t care how you do it.’ Of course, I was on the set every minute.”

Dick hadn’t encouraged June to take the part in “Right Cross,” because, “at the beginning, the girl’s part wasn’t big enough for her. I didn’t want her to do it.” But June wanted to do it because Dick was already cast for it. “Then I had to work to help build her part and get her into the picture,” he laughs.

During the production of this one, when June was ill with virus and laryngitis and was so anxious not to hold up production, Dick would take her temperature every morning and say, “Now if you feel well enough, you should go to work.” He didn’t soften completely even when their little daughter came to the door sympathizing, “Oh ter-ble, ter-ble,” saying the important words twice, as she always does. “What’s wrong, baby?” her mother asked. “What kind of trouble can a little girl like you have?” And Pamela said, “Oh, Mommy, bad cold, bad cold.”

“He never babies me,” says June of her star husband. But what she didn’t hear were his concerned consultations with the director, checking over the shooting schedule, trying to find some script loophole for her, worrying, “She just can’t keep on working with fever every day.”

At eventide, when Dick and June come home together from the set, they rush to their rooms, put on their pajamas and robes, eat dinner, rehearse their lines, play with Pamela, and make plans for their expected new arrival. “I had a phone call this morning. I think we’re having a baby,” she announced one day to Dick. They don’t know when the new adopted baby will arrive. “They just call and say, ‘Your baby is here.’ We put in an order, a long time ago, saying we wanted another baby when Pamela was two years old, and she’s two now. I want a boy. Richard wants a girl. So we just said, ‘Surprise us!’ ”

Every evening before rehearsing their scenes, June and Dick padded up to the attic in pajamas to see how the new baby’s nursery, still in a state of plaster and loose boards, is coming along. Blue-printing the whole layout, Dick would tour her through saying, “The beds go there,” pointing in one direction. “Where? Oh!” June would attempt to follow. A chest would go in that alcove. “Where? Oh, I see.” Another bureau here. The tour to be eventually interrupted by June’s “Ouch!” as a loose board met her, head on.

About that old temperament taboo of actors taking their roles home with them, June says readily, “If you mean the ‘Reformer,’ well, yes!” Intimating by her mischievous tone that one Richard Powell didn’t really have to take this role home with him, it sort of beats him there.

“He’s always reminding me of things. ‘Please, doll, answer the phone when it rings.’ (I hate telephones.) ‘Please don’t make an appointment and then forget about it and take Pamela for a pony ride instead. Please put gas in the car so I won’t be stalling in the middle of Sunset Boulevard. And if I say meet me at Romanoff’s for lunch, please, don’t sit in La Rue’s and wait.’

“But he’s very polite about it. It’s always, ‘Please,’ ” she grins, “except once in a while it’s ‘For the luva . . . ! June, please!’ I try, I mean well,” she laughs, “but I have so much on my mind.”

Pamela’s “Mommy” is prone to drift dreamily around the house from room to room carrying the new silver mink cape Dick gave her, “and for nothing,” she says, as she hangs it over the knob on the desk drawer in the den and gives it an umpteenth loving caress.

The silver mink came as a joyful surprise when Dick walked in with a big box and threw a line away, something about, “Honey, I bought myself some shirts, see if you like them.” It seems June, recently torn between the desire for a silver mink and having her engagement ring reset, decided on the engagement ring and Dick wound up by compromising, and giving her both. “I really think he gave this to me because he wants to go fishing. He’s so cute,” June grins.

When they make another picture together June would like it to be “Too Young to Kiss.” “It’s a light comedy I’d love to do with him. He hasn’t seen the script yet. Besides, he says he doesn’t want to work with me all the time or we’ll get in a rut. Which I think is pretty rude!”

When Pamela is a little older, June would like her to join them. Then the other baby will be growing up and, “Just call us the Perennial Powells,” she laughs, then calls, “Richard, wherefore art thou?”

“Right here,” he says, having entered on her last line and giving his private-eyeful what is known as the stare.

“You know,” he says with a semi-sad look, “on third thought I may make another picture with her. The kid needs me.”

Says his leading lady, “You’re so right.”

THE END

—BY MAXINE ARNOLD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1950

No Comments