The Personal War Of Audie Murphy

A war hero, a modest young Texan with a baby face and cool, gray-green eyes sat squirming on a platform in the home-town square. Squirming and uncomfortable while the bands played, crowds cheered and perspiring orator after orator eulogized him.

Home was the hero—and Farmsville, Texas was determined to do him proud. Audie Murphy had every decoration for valor his country could give in one war. But he wasn’t through fighting. Not yet.

He’d made the round trip—to hell and return. How he came back, he would never know. But ahead was another kind of enemy.

Life. as he’d known it, was poverty. Desertion by a father he never again wanted to see. Quitting school to work and help feed a brood of younger brothers and sisters. And losing the one human being really close to him. the one who should have been there this day, a weary, gentle woman whose dark eyes used to shine with her pride and faith in him.

“If only Audie had a chance, he’d really make something of himself someday. I know he would,” his mother, Josie Murphy, used to say. She didn’t live to see that faith fulfilled. But she had known anyway.

Audie had cried unashamedly three days when she died. And he’d sworn then never in this life to cry again. It was a long time before he could.

Back from the war, he could have used some of his mother’s faith. To Audie, who’d been living one hill at a time, life still seemed a very temporary thing. He’d made no postwar plans. His one thought of going to West Point had died with that last shell—with the hip wound and the gangrene that later set in. Other than war, his experience was farming and repairing radios. So when Hollywood, attracted by his war record, his handsome baby face and the attendant publicity, summoned him to be an actor—as incongruous as it seemed to him—Audie went along.

“It seemed so funny. I hadn’t even seen many movies. Me—going to Hollywood.” But he was a gambler, and the way he figured it then, he had nothing—or next to nothing—that he could possibly lose. So why not take a great big gamble?

He was almost wrong. For during those first struggling years, he. lost the little faith that remained, the little hope he had. As he knows now, “In this life—hell is wherever you find it.” As he had already suspected, life can produce more than its share. It comes in all shapes and sizes—in loneliness, insecurity, the restless search for something to live for. For something, for somebody to believe in, for somewhere to belong, in learning how to go with life instead of against it.

Today, ten years later, life is no longer Audie Murphy’s enemy. Today he can laugh, and he laughs often. He can cry, and in “To Hell and Back” he does cry again. Today he’s alive. He can feel again. And life is no longer a temporary arrangement to him.

He’s found something to live for, Audie says now, with a loving look for three-year-old Terry and for Skipper’s black curly head, as his youngest toddles shakily around the den at home.

Today he has a more relaxed philosophy for living. And for all his decorations, he can accept small defeats on the home front like a man and a father.

“Terry, don’t tie up your baby brother,” Audie will entreat, rescuing Skipper from the noose just in time. And observing his German Shepherd dog playfully tossing a swatch of something khaki about, say mildly, “Pam—Ranger’s got my gloves again—or else he’s grabbed the gardener.”

But he’s no less brave, civvy pink sports shirt and all. He’s a far different Audie from the restless one who used to burn up the highways to drive away his insomnia, who used to keep Highway 80 hot commuting between Texas and Hollywood, who still took unbelievable chances and to whom life meant so little.

As Audie says, “The stakes are a lot higher when you’re married and have children than when you’re footloose and fancy-free. I don’t take chances anymore. And that’s been the hardest thing for me to learn—not to accept every challenge that comes along. I got away with a lot of things during the war. I could justify the chances I took then. But I couldn’t justify them in civilian life now.

“Until now, I never could resist taking a chance. If anyone said, ‘This can’t be done,’ I wanted to be the one to do it immediately. But children and responsibilities make you lose your guts. Or maybe I should say you gain the right kind of courage,” Audie adds quietly.

“Another thing, I don’t drive like a maniac anymore. The most dangerous thing I do now, believe me, is endeavoring to get home alive in that freeway traffic every night. And you’ll never guess where I got this,” he grins, of a sprained thumb, “fighting a losing battle with a revolving door.”

Yes, he’s another Audie, a younger Audie, than the lonely restless Joe you used to meet at a small cafe on Hollywood Boulevard for coffee and to exchange a few words about Texas. Pretty heartbreaking then, seeing one who deserved so much from life, taking so much on his granite chin.

He’d come to Hollywood at a time when the whole world, it seemed, wanted to forget war. Agreements made with him were broken again and again. Pictures promised him were never made. He got offers for advertising tie-ins and publicity-package deals from those who wanted to cash in on his medals, but Audie wouldn’t commercialize on his war record at all. He skimmed by on his $86 pension some of the time. He was still living life one hill at a time. And the way he drove an automobile didn’t promise to lengthen it.

Seeing Audie now so healthy, so alive and in such rugged shape for his prize-fighter role in “World in My Corner” at U-I, it seems almost unbelievable that he came to Hollywood with a game hip and a limp and with his nerves and whole temperament triggered from war.

He couldn’t eat and he couldn’t sleep then. Home was wherever he felt comfortable hanging up his field jacket. A noisy one-room apartment in Hollywood over a bus stop, or a motel in Dallas or a massage table in Terry Hunt’s health club, on which he bunked for quite a while. Sometimes when he talked, the scars inside him—deep inside—would bleed through. The gulf between soldier and civilian was just too big and too painful to bridge. The buddies who’d died were still too alive to him. During sleepless nights he began to think about putting them on paper, so the world would know their story. He wanted to get it all down “so I won’t have to think about it any more.” He was an officer in John Ford’s chapter of “The Purple Hearts” and he visited veterans’ hospitals to boost morale.

But this was almost too much for him, and he was understandably upset about the public’s seeming apathy. “I just can’t go into a hospital. It makes me too ill—seeing those guys lying there—stuck there like yesterday’s newspapers, and so few people remembering them.”

He’d stood off a German army almost singlehanded, but in life Audie was afraid to let his own guard down lest when he wasn’t looking somebody might slug him from behind. He had a cynicism he knew he should shed. But how? “I want to believe in people. I really want to but—” Audie would say, although little had happened which should have inspired any faith in him then.

He liked working in pictures when he could get work. They didn’t tie him down to any one place. He liked the stimulation of a constant change of characters and backgrounds. “But if I left tomorrow and didn’t look back, I wouldn’t care,” he’d say. He thought he might like a ranch in Texas. But ask Audie what he really wanted and he would admit he didn’t know. He’d made one unsuccessful attempt, and it seemed he just couldn’t take root anywhere. “I’d rather be married than to be out on the town. I want a home and family,” he would say. What he didn’t talk about was the terrible gnawing fear inside him that two serious attacks of malaria might have defeated this, too. That he might never be a father. Never have a son.

Gradually, he began to live again. He made an effort, however halfhearted, to fit in and feel at home. He rented a bungalow in a court and he added a few homey touches like Western paintings, bronco book ends, horns over the fireplace and a busy electric coffeepot. He got a contract at Universal-International and the future came more alive for him. Then he met a pretty Texas air-line stewardess whose shining eyes fairly worshipped him. Her fan-worship was better than any physical therapy for him then. And more than she probably realizes, Pam Murphy and the sons that followed inspired Audie Murphy to live and to lick life’s problems.

Audie had to learn to live again before he could relive the war and those many months with all his buddies of Company B, 15th Infantry and the Third Division’s war in “To Hell and Back” on the screen.

As he says now, “I’ve always felt their story should be told. I just play a part in it. This isn’t just my story—it’s the story of all our company and of the Infantry. There’s going to be one hell of GI jury looking at this film and reviewing it out front,” Audie adds with a wince. They’re the critics he’s concerned about. “I feel we’ve made an honest effort to bring the story of the U.S. Infantry to the screen. I hope the guys will all think so—but you can’t feed on hope. You’ve just got to wait and see.”

At this writing, one “juror” hasn’t even had the nerve to go see it, to see himself as Audie Murphy, war hero. Only his strong feeling that their story should be told and telling himself he was just an actor—just playing a part in it—pulled him through making “To Hell and Back.”

“It would have been tough if I hadn’t been so busy all the time. I was sort of an assistant technical director on it and I was helping out with these things. If I’d had nothing to do but sit there and do my little part—I’d have gone nuts!” he says.

But it was tough duty anyway. Reliving the death of Lattie Tipton, of Tennessee (Brandon in the picture), Audie’s best buddy throughout the war, who died in the foxhole with him, was almost too tough. Audie helped cast every part—and he decided on Charles Drake for this all-important role. “I’d known Drake for some time. I liked him—and he has the same quality of quiet dependability Lattie had. That was the toughest scene for me to do,” Audie adds slowly. “It should have been easy. I had had to think throughout the picture, ‘This isn’t me. I’m somebody else,’ so I wouldn’t worry about under- playing it. And in this one—”

The whole company was glad to get through this one, as director Jesse Hibbs says now. “Audie wasn’t doing much acting in this. He played it as he felt it. His lips were quivering and his eyes filled. Audie had been nervous that day, knowing the scene was coming up. He knew what I wanted from him. I wanted tears. Still, it was a hairline scene and we couldn’t go overboard. When Charles Drake was hit and cried out ‘Murph!’— Audie wasn’t acting from there on.”

There were many rough spots during the filming of “To Hell and Back.” As the director recalls, “It was like pulling teeth for the first three months when we were planning the picture—just getting Audie to talk.” Then gradually it came out. Being so busy helped him become more objective about it, until he could think of Murphy as a character in the picture instead of himself. But there were still some tough days. In the scene in which his mother passes away, we all cried.” They’d explained the scene to the child who was portraying Audie’s younger brother, and when the cameras started turning, the little boy started crying as if his heart would break. This was finally too much. As if on cue, Audie’s long-damned emotions broke through.

They couldn’t put Audie’s whole story, the dramatic story behind every medal, on film. Nobody would believe it. As Audie says when pressed, “Well—we played down some scenes out of necessity. Truth is realistic to read about, but when seen on the screen it can look exaggerated.”

Pam went to the first invited showing of the picture. Even hardened members of the press came out of the theatre misty-eyed with the honesty and heart in Audie’s picture.

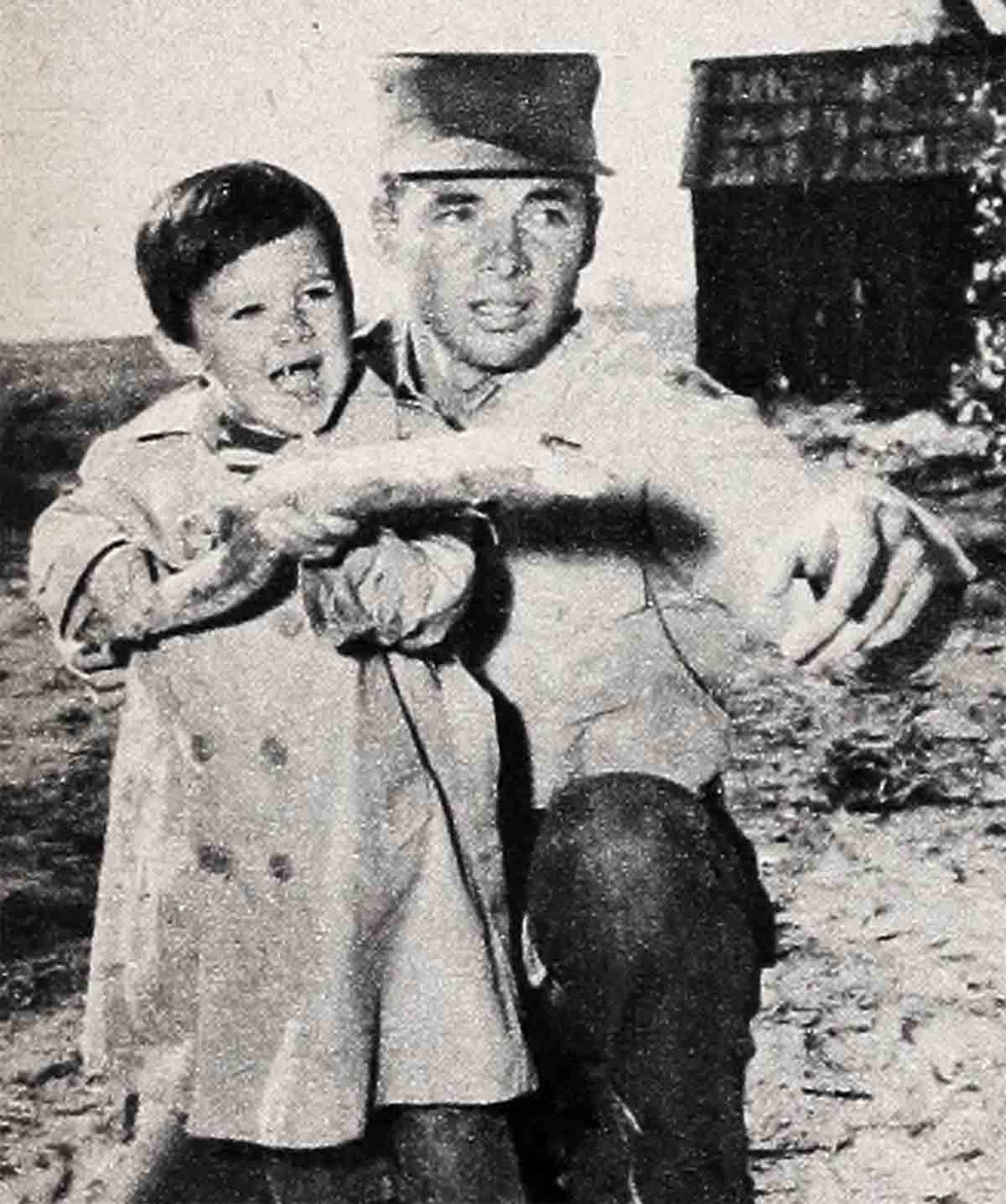

His three-year-old son, Terry, portrays Audie’s youngest brother in the childhood sequence, and he threatened to hold up the entire war. As Audie says, “Terry has a couple of mouthfuls in it,” but he was a busy little man padding his part. The scene called for Terry to be playing in the family woodpile when Audie came home carrying a rabbit he’d shot for supper. His line was, “Did you get another rabbit, Audie?” And his father had rehearsed it with him over and over so he’d be ready when his moment came. But when the stage quieted and cameras started turning, Terry ad libbed, “Action! Roll’em!” taking over the direction. This broke up the company and Terry decided it should stay in and he kept repeating it. When he was finally prevailed upon to inquire whether Audie had another wabbit, as his dad recalls, “Terry picked up a stick of wood, aimed it at my rabbit, and said ‘Bang, bang bang!’ He threw this in with no extra charge.”

He may not take chances anymore, but today isn’t without its challenges for Audie. “Just being a father is challenge enough! I come to the studio and work out three hours in the boxing ring and I’m not too tired. I stay at home with these boys three hours and I need a vacation.”

Skipper, Audie’s younger son, who has black curly hair, has a large sense of rhythm and loves to dance with his dad. Every night when Audie gets home from work he has to take a delighted Skipper for a few rhythmic turns around the room. Meanwhile, Ranger’s found a loose paling in the fence and initiated a cold war with the neighbors by going AWOL, and Audie must repair the fence. Then there’s the instrument panel for Terry’s big jet plane. “Terry’s deserted the Infantry. He’s a jet pilot now,” Audie explains. “He wants a ‘man-sized’ jet plane for the back yard and I’ve got to get it put together some way. I’ll get a tail and a stick and get some instruments for a panel from the war surplus for him to fool around with. The studio special effects department’s going to help with the body—they don’t know it yet. But the boy’s so mechanical-minded I want him to stay interested,” Audie says, groping for a fatherly out.

Then he adds, “You love them so much, you have a tendency to be too lenient. You’re overcautious with them, too. But you can’t clear a path for them forever. You’ve got to let them fall down and pick themselves up again. I keep telling Pam this. You can love them so much you just make everything too easy for them,” Audie says, eagerly extending a hand to each. One thing sure, their father is going to see their path is never as tough as was his.

All Audie’s anxiety for his own sons is in his voice in “To Hell and Back,” when he pats an Italian child on the head with the hope this lad will never have to go to war. When a fan gushed, “I couldn’t help thinking of those two boys of yours,” Audie said, quietly punching every word home, “And whom do you think I was thinking of?”

The other day Audie and Terry were scheduled to make a savings-bond film together at the studio. When Audie arrived with a well-scrubbed and beaming Terry in tow, he blanched a little as he heard a nurse could not be found to care for Terry. “Look, we’ve got to have a nurse. On the lot he’s too much for me.” The nurse came; Audie sighed his relief.

In the scene, Audie was to chat with a clerk in a bank and tell him how Terry had invested the $300 he made in “To Hell and Back” in savings bonds, which was true. Terry was to agree. Yes, he surely did. But when the clerk smiled at him fondly and said, “Did you, Terry?” Terry drew himself up to his complete height and said haughtily, “I surely did not!”

“Terry’s like me,” says Audie. “When somebody says ‘No’, I want to say ‘Yes’ immediately.”

But not so much today. Much of Audie Murphy’s innate sense of rebellion has simmered down. Today he’s mellowed more to going with life, instead of counter to it. And he appreciates the necessity for teamwork in life, as in war. He’s more adaptable and he works to be. He’s no longer a lone wolf and he doesn’t spend as much time with his horse and his rifle. He socializes more.

“If I didn’t have Pam and the boys, I think Id still be completely happy living as a hermit. But with a family, you can’t get so self-sufficient you don’t need anybody else. Your wife wants companionship. Your children need friends.”

Audie admits living as a family unit has tempered his own trigger-timing, too. “With a family and responsibilities, a kind of slower evaluation sort of grows on you,” he says. “I’ve always had to make instant decisions, but with a family and with Pam’s temperament, you just don’t do that. Some people just aren’t geared to move this way. And Pam exercises that feminine prerogative of wanting advance notice. I have to tell her ahead and give her a chance to work out plans.”

He owns half-interest in a cruiser he keeps at Balboa and uses for skin-diving expeditions now. “It’s just a tug. We call her ‘African Queen.’ She sleeps four people.” He finds skin diving “fascinating—like another world”—and about the only thing new to do. “I never could do anything unless there was a challenge involved. I couldn’t swim very well—that’s why I took up skin diving.” During Audie’s childhood there was no time to go swimming in the creeks.

He’s learning, too, that patience, however painful, is a necessary family virtue. “When we went to Balboa for a three-day trip, it took Pam two days to pack to go away for three days,” Audie grins. “Instead of just going away for the weekend—the two of us and relaxing—Pam insisted on taking the children. We had to employ a baby-sitter when we got there. Then it seems there was no crib and we had to buy a crib for the baby. Pam’s sure the baby can’t sleep unless he has a crib. Right away—problems—and no rest or relaxation for anybody.”

“And I got so sick,” Pam recalls. “They had to turn the boat around and take me back to land and we were two hours out at the time.”

There was then the problem of getting them all safely and peaceably home on Sunday. Audie thought he had the whole tactical maneuver planned. If Pam wouldn’t give Skipper his scheduled bottle, then give him mashed potato at the dinner table, then give him his bottle on the way home, “He’ll sleep.” But, “We have to wait thirty minutes for Pam to give him his bottle right on schedule. We finally get him to the dinner table and he won’t eat and won’t let us eat. He tears up crackers and showers them upon us. Then he raises ole Billy in the car all the way home,” Audie says, shaking his head.

Honesty, however, nudges him to admit he doesn’t like to go away for a weekend without them either. “Those little guys —they get such a hold on you. You miss them so much it’s hard to be away from them.”

Audie’s humorous tolerance of feminine “prerogatives” and the way he’s acclimating himself to a family’s slower tempo for living reflects his happiness today. “Pam and I have had some pretty rough spots in our marriage, but they’re behind us now,” Audie says quietly, with a tone that says that’s just where they’ll remain.

The wounds of war take a lot of healing. When they were first married, Audie’s tension, his fatalistic outlook and his more reckless pattern for living—the long chances he would take—jarred with Pam’s sensitiveness and her naturally cautious and conscientious approach. She went into matrimony with stars in her pretty dark eyes and wearing rose-colored glasses. With her fan-worship, she was unprepared for the inevitable time when star dust would dissolve into reality. Theirs have been important adjustments and they’ve made them. They made them because they were strong enough to carry them through, to bridge the difficulty.

“Pam’s more conservative than I am. She hates any kind of gamble. Like most women, she wants a sure thing. There’s no such thing. But I don’t gamble on anything any more,” Audie says seriously. “I wouldn’t even bet the Statue of Liberty can’t swim the Hudson.

“Pam thinks from day to day and I’m getting to where I try to think from year to year. But in long-range planning you can forget and let little immediate things go to pot—and you shouldn’t. You can temporarily forget today and get thoughtless,” Audie says. But today isn’t slipping away from him now and those long-range views are more important than ever. Working for security for those so important to him. Audie is finding a satisfaction he never knew.

“In the past I’ve never cared enough about money or security. I’ve never managed or saved as I should have. And for a long time I wasn’t overly interested in my career. I couldn’t get over the feeling I missed out by not going to West Point,” Audie goes on. But now the Murphys have a business manager. They have budgets and they stick to them without fail.

Now Audie Murphy’s working, building, saving and planning for that future which never used to seem real to him. Recently he signed a very fat new contract with Universal-International for two pictures a year with the right to make an outside picture with a one-third participation in the profits. A real dream-deal. Audie “waited out” the final stages in the negotiations alone. As he says, “With Pam’s so-called practicality, I had the feeling she wasn’t up to waiting it out.” And it was too much for her. “Just don’t tell me anything about it until it’s all over,” she said.

But any gambles Audie takes today are for their future. The four of them. He no longer commutes in life. His restless search for something to live for—for somewhere to belong—is through. Today he finally owns a “piece of Texas.” Recently he bought what Audie refers to as “a farm with a few milk cows,” near Dallas. Actually it’s ninety-three acres with a handsome two-story air-conditioned home. “But I bought it mostly as an investment. It’s too far away for us to spend any time there or really enjoy it. I’d rather get a ranch some place around here— closer to my work.”

Today, Audie is planning to build a place “in or around Toluca Lake—Pam likes it there.” The boy whose full heart always belied the cool gray-green eyes and poker mien is back from the wars to stay. He took his medals off and fought his way up to the front again. And he’s finding that life can be a rewarding victory.

Today when Audie swings into his driveway from the studio he’s welcomed by his own company of noncoms. By a wagging “Ranger,” who stands rigidly at attention, holding his feeding bowl in mouth, waiting for chow. By Skipper, who breaks ranks and toddles delightedly toward him. And by a three-year-old jet pilot who fairly streaks to meet him at the door.

“Daddy! I’m so glad you’re home,” Terry said the other day.

“So am I,” said Audie, swinging him up and holding him close.

He had to go to hell and back—and win two wars to get there.

THE END

—BY MAXINE ARNOLD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1955