Rory Calhoun’s Gone Hollywood

THE REDHEAD WAS MIGHTY PRETTY. The “picture fellow,” Fred MacMurray, looked husky enough to be a ranger himself. But surveying the movie location scene being filmed, Forester Francis Timothy Durgin felt no envy. He wanted no part of it, this play-acting in his redwoods.

He was a native of the tree-country. Lean-hipped, with wide shoulders and a sun-warmed smile—his blue-green eyes were alerted for any flicker of flame, his senses keyed for the smell of smoke. He’d been assigned by the Division of Forestry to make sure the movie company observed every fire law. And he was observing.

AUDIO BOOK

“I heard people scream and holler,” he remembers.

“And I heard all the whistles blowing. What a hassle, I thought. What a way to make a living!”

Just let him earn his keep under the open sky. Give him the rich coloring of the redwoods, the sounds of the forest, and the music of the river. His was a stage of majestic splendor.

In his watch tower he was king and guardian of all he surveyed. Actors. What a way to make a living!

Forester “Smoky” Durgin had no way of knowing then that two years later he would be a “picture fellow” named Rory Calhoun, up to his expressive dark eyebrows in the same profession. Or that his performance in “I’d Climb The Highest Mountain” with the “pretty redhead” would determine his whole future, and that some day he would be co-starring with Susan Hayward, too, in “With a Song In My Heart.”

However, in the time that followed—the years between—he had wanted no part of Hollywood, itself. During those first few years in movies, Hollywood and acting—his acting—seemed too insecure. He was making no permanent mark in motion pictures, and getting no solid roles which assured him he ever would. True, he was getting parts, but the whole thing was too temporary. He began looking for ranches and land to invest in. Back to the open spaces for him. A man could put his faith in land. Together with his bride, dancer Lita Baron, and her family, Rory invested in some property which soon doubled in value. They bought another ranch, 165 acres near Ojai, which they converted into a guest dude ranch called “The Rocking Star.” This was Rory’s real security.

But then Rory’s own star began to rise. No less an authority than Director Henry King sought him for a role in “I’d Climb the Highest Mountain,” with Susan Hayward and William Lundigan. This picture changed Rory’s whole future. Fan mail flooded the Twentieth Century-Fox studio for the dark, handsome ex-fire-fighter who suddenly torched the hearts of feminine fans everywhere.

Twentieth proved its faith in Rory by signing him to a long-term contract. It was after “I’d Climb the Highest Mountain” that Rory Calhoun, too, began to have faith in his future as an actor. “When the studio sent for me for that picture, and when, following the picture, they put me under contract with a sizeable jump in pay—then I thought, ‘Now I have a chance.’ I figured they must have believed in me—giving me a part like that.”

The studio put him in “With a Song in My Heart.” Then they gave him the colorful starring role in “The Way of a Gaucho” which practically cinched him as one of the screen’s most popular romantic leading men. Following this, came his present role in “Powder River,” with Cameron Mitchell and Corrine Calvet.

By then, there was no shadow of a doubt left in Rory’s mind. He was for Hollywood—and his rapid rise to success proved it conclusively—Hollywood was for him. But to Rory, who still kept the tang of the pine forests dear to his heart, that didn’t mean changing his entire way of life. He vowed he would never trade the wide open spaces for the heavy air of the night clubs. And he hasn’t done it.

His credo has always been, “I live the way I feel, so long as it doesn’t hurt anybody else.” And if that means that Rory’s uncomfortable from time to time, he can be philosophical about it.

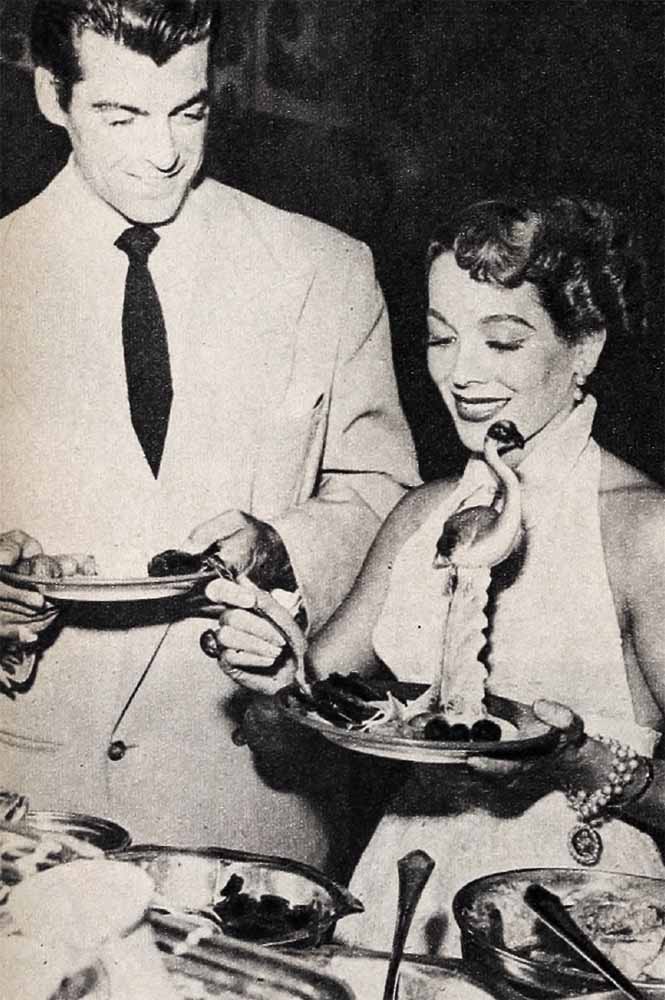

Night clubbing is a case in point! Although the pastime is anathema to Rory, his wife, who once sang with Xavier Cugat’s band, under the stage name of Isabelita, loves the bright lights, the hum of conversation, the tinkle of glassware. And if that’s what Lita wants, Rory sees to it that she gets it.

Lita is equally cooperative about Rory’s enthusiasms. His daily seventy-mile drive from their Ojai Valley ranch into Hollywood—just so he could be sure that the air he breathed when he got home at night was fresh and free of gas fumes—may have struck her as a little less than convenient. But she went along with the arrangement.

And for a gal who had never approached a gun at closer range than the ones she saw flashed on a movie screen from the safe distance of a loge seat, she reconciled herself completely to the small scale armory of hunting irons that Rory keeps on hand. And she’s as attached as he is—almost—to the collection of antique and unusual guns that Rory tends with the love of a museum curator. She even understands that a hiking type guy like Rory needs the solitary walks he takes out over the hills, with just his dogs to keep him company.

And Rory, for his part, knows how well his Lita understands him, and how lucky he is to have a wife who doesn’t try to make him over. For his sake, she’s learned to respect riding and shooting and hunting. For her sake, Rory has learned to dance—and Lita, who makes her living on her toes—says that he can samba and rumba with the best of them.

Actually, adding it all up, it’s really not a very great change from the old Rory Calhoun who began his wanderings when he was a boy of ten. He’d take off into he hills near his home town, Santa Cruz, California, with his 22-rifle, knapsack and his dog, “Rags, avoid searching parties and disappear for days at a time . . . ever eager to commune with Nature, even at the expense of communing with a concerned parental hairbrush when he finally returned home.

“I loved the out-of-doors. I was always a kid wild for adventure,” Rory says now with his slow smile.

He hired out as a bronco-buster on a ranch near Tombstone. He worked as a hardrock miner in a silver mine outside of Reno. Worked in a logging camp. Hired out on a fishing boat. He dug ditches in the Oklahoma oil fields as a roustabout. With ambition and resourcefulness to match his energy, Rory Calhoun kept roving around, searching for his own particular sphere, trying to discover what he could do best—where he rightfully belonged. He went back to his hometown—to the forests, his first true love. Digging in, he determined to become a ranger.

He’d never so much as emoted in a school play. “I was of the opinion acting was strictly for softies,” he says, wincing at the word now, and remembering the long weeks he spent alternately working in freezing snow and ice high in the Andes, and sweating in the blistering dust-choked plains of Argentina for “The Way Of a Gaucho.”

But all this fire-fighter “Smoky” Calhoun had yet to discover. In 1944, he took a two-week emergency vacation from firefighting and went to Los Angeles to visit his ailing great-grandmother. This is when, by happy accident, he became an actor.

Early one morning while riding in the Hollywood hills, he met a likable fellow on the bridle path who later turned out to be Alan Ladd. “I didn’t recognize him,” Rory recalls. “We talked for ten minutes, mostly about horses.”

“Are you an actor?” Ladd finally asked.

“Thunder no,” said Rory, realizing too late why this fellow looked so familiar.

“Would you like to be an actor?” Alan smiled.

“No,” said Rory, adding, “I don’t know anything about it.”

His wife, Sue, was an agent, Alan told him. Sue could get him a good coach. Flattered, but hesitant, Rory lunched with Sue and Alan in their home and agreed cautiously, “Well—I’ll stay thirty days.”

He was studying to be a ranger. Even going to night school. And he’d worked too hard for it to take any long gamble.

Sue Ladd got Rory a job right away, playing the part of Jim Corbett in “The Great John L.,” a part which she knew wisely enough, would require little of him. He worked three days and he had one line. “I’ll do that, Champ,” it was.

And for this he was paid $600. “As a forester I’d been making $78.40 a week. This was tremendous pay. Two hundred dollars a day—how could you turn that down?” asks Rory.

There followed a part in “The Bullfighter” with Laurel and Hardy at Twentieth Century-Fox. He could handle his dialogue in this too. “If that guy’s a bullfighter—I’m Mickey Mouse,” was his worthy contribution.

To a practical young man who’d worked so hard for a dollar, Hollywood seemed an almost unbelievable place. These people were crazy, but as long as it lasted, they could count him in. He decided to put his realistic mind to the business of making motion pictures. “I thought acting was like a vacation with pay. . .” Rory grins now, adding, “when I got paid.”

For there were lean days when, having made acting his business and having given up his job at home, he needed all the ingenuity and athletic ability of which he was capable to stretch a dollar.

There were no dreams in Rory Calhoun’s eyes, then or later. No Shakespeare in his soul. Making movies remained just a job. But acting, he discovered, was a trade. “If you’re an apprentice, you learn. Then when you’re a craftsman, breaks come your way. I found I was an apprentice then. I’m not a craftsman now—but I’m learning.”

Twentieth Century-Fox signed him to a stock contract, and Rory, by now sold on the fact that he needed both training and experience, got jobs on the side to augment the small stock salary. He spent his days at the studio and worked nights as attendant at a Beverly Hills service station. When he was on lay-off, he worked in a brick yard near the studio.

Rory got a few small bit parts now and then, including one in “Sunday Dinner For a Soldier,” in which you won’t remember him. “One-Line-Calhoun,” they called him then. His greatest performance was trying to out-talk his creditors, such as the one who eventually took back his ’35 Oldsmobile.

When Twentieth Century-Fox dropped his option, Rory wasn’t surprised. “I figured I didn’t know anything about acting. I expected it. Disappointed? A little, but I didn’t let it throw me.”

About this time Henry Willson, then a Selznick studio executive, and today one of Hollywood’s star-discoverers and most famous agents, saw Rory at a party given by the Ladds. He noted the way all the girls present kept ogling Rory and recommended that his studio sign him. One of Rory’s best parts during his five years at Selznick-International was a loan-out for “The Red House.”

Then Twentieth Century-Fox borrowed him for “Sand.” Although he couldn’t foresee it, Rory Calhoun’s future was developing. And in more ways than one.

For about the same time he met a beautiful little Spanish dancer, Lita Baron, who was leading her own orchestra at the Mocambo. Rory was intrigued by the diminutive dancer with the flashing green eyes and the warm, vital personality. One night he stagged it to the club and invited her to join him when she left the podium. “I’m not allowed to dance with the customers,” she demurred smilingly.

“But I’m not just a customer,” he said.

Later, he asked if Lita had someone to take her home. “My brother always comes for me,” she said.

“Well, if you’ll trust me, I’d like to take you,” said Rory.

They stopped at six drive-ins on the way home. “A kind of drive-in marathon!” laughs Lita now, remembering how they ordered a sandwich one place, a dessert another, and coffee four times.

For Lita and Rory it was love at the first drive-in. “I admired him so,” she says. “Rory didn’t act like a big shot, like a celebrity. He was such a regular person,” she says, her eyes shining the way they do whenever she speaks of him.

“Lita? I liked everything about her,” says her husband. “She was very sweet, but with the fire and spirit I liked too. And such a nice, clean girl. Maybe I’m old-fashioned, but I could tell she was a girl who’d make a comfortable home and who would want a family.”

When Rory went to Durango, Colorado, on location, he sent her a silver fox cape which was initialed “I.C.C.” “What’s the other ‘C’ for?” her brother teased Lita, whose real name is Isabelita Castro.

“I don’t know. Maybe it means Interstate Commerce Commission,” she laughed. But she knew it was Rory’s way of proposing to her. “I think you made a mistake and sent the cape to the wrong girl,” she told him that night when he called.

“Why?” he said.

“Those aren’t my initials,” said Lita.

“They will be,” he said, his voice slow and serious, “if you want them to be.”

And so shortly thereafter, they were married one summer Sunday morning in Santa Barbara, with the old mission bells ringing melodically in the background. And now Rory Calhoun was gambling for two, himself and a brunette vision in grey chantilly lace.

But after eight years in motion pictures, it was the starring role as the South American Gaucho, the rugged, handsome horseman of the pampas, untamed and passionate, fighting for love and for his own ideals, that convinced Rory Calhoun that he was probably in Hollywood to stay. And it was during the making of “Way of a Gaucho” that Rory ! realized his heart, as well as his wallet, was all wrapped up in his work.

“It came to me during that picture—that I enjoyed this kind of work,” he says seriously. “The role of Martine I liked. I’d played the other man’ many times—but to be a good guy and a heavy at the same time as in this role was a stimulating challenge. Besides, I liked the guy.”

It was while they were in Argentina, too, that Rory Calhoun realized first-hand how great was the impact of his adopted profession, how warm the spot Hollywood’s stars hold in the world’s hearts. He was surprised to find fans there even knew him, and he was touched by the way droves of them followed him around wherever he went. Two hundred followed him to a bar one evening, and while Rory sat inside having a sandwich and a beer, they stood outside mutely watching him. “Those people can’t stand there,” the tavern keeper said angrily.

Finally he became fairly violent about it, threatening to use force to disperse them. “You can’t stay out there,” he was saying, when Rory moved in and convinced him they could.

“They’re my friends,” Rory explained, when the fighting was over.

He invited all two hundred into the tavern and bought a round of drinks. He couldn’t speak their language, nor they his. He was a stranger in a strange country, but he was surrounded by friends. Because of motion pictures, wherever he might go in this world, he would find friends. It was a warm and wonderful thought.

Now Rory and Lita have another wonderful thought. They plan really to take root in Hollywood. They want to buy a lot and build their own house. In the meantime, they’re going to dispose of their “Rocking Star” ranch. “I want to sell it. I don’t have the time to devote to it. Acting is my business now,” says Rory the ranger. He has found that his own particular trees grow greenest in front of a camera.

Rory’s gone Hollywood. He’s come home.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1952

AUDIO BOOK