The Truth About Mr. And Mrs. Curtis

Pretty soon now, on June third to be exact, Tony Curtis will take Janet Leigh in his arms on the second anniversary of their marriage and together they can exclaim, in some wonderment, “Well, what do you know—we made it!”

That two years of wedded bliss should be considered such an incredible achievement may seem a little silly; yet, statistically speaking, Janet and Tony are rare birds on Hollywood’s domestic scene. They know it, too. In their almost 24 months together they have hung on tight to each other as they watched long parade of movie marriages smash up: the John Waynes, the Gary Coopers, Lana Turner and Bob Topping, Rita Hayworth and Aly Khan, the Dan Daileys, Olivia de Havilland and Marcus Goodrich, Barbara Stanwyck and Bob Taylor, Anne Baxter and John Hodiak, the Clark Gables, and now the separation of their close friends, the Dean Martins.

No wonder the ladies and gentlemen of the press look upon any Hollywood marriage with jaundiced eyes. No wonder, too, that Tony Curtis speaks with some venom and utter seriousness from his own point of view:

“If people would only understand that motion picture figures have the same right to fall in love as anyone else, that they have the same feelings and the same emotional honesty as plumbers, bank clerks, executives or insurance salesmen. If they’d only understand that. We’re not phonies. We bleed and hurt and love like anyone else. But take Janet and me, the things they said and wrote about us for a while, you’d think we dreamed up the whole thing for a couple of bucks at the box office.

Tony still steams himself up violently when he thinks about it. “When we were engaged, and she was wearing my ring and all, some New York columnist wrote that Tony Curtis better get himself a new press agent, because Janet Leigh had fallen in love with someone else and Was going to marry him. Man, that was rugged!”

Man, it certainly was!

When the synthetic news that his girl was about to throw him over reached Tony, he came mighty close to a nervous collapse. He was in Denver, Colorado, on the first big personal appearance of his career. So great was his appeal for the opposite sex that after one stage show, he had to hide backstage for an hour before he could safely be smuggled back to his quarters at the Brown Palace Hotel. Girls of all ages were trying to rip off unanchored bits of clothing and he had been kissed once too often that day by passionate, predatory females.

Back in the comparative safety of his hotel suite, he tried to reach Janet by long distance telephone. She had been attempting to reach him all that day, with no success, because the operators were obeying orders; Mr. Curtis didn’t want to speak to any eager young ladies. They’d have to leave their names and he’d call back.

Of course, there was some comfort in the dozen messages under his door, asking him to call Miss Leigh in Pittsburgh, but when he couldn’t get through his normal reaction was the sneaking suspicion that perhaps, after all, there might have been some truth in the story that Janet had met up with a fascinating baseball player and, so to speak, flipped her lid. It was three o’clock in the morning before the connection was made. Then, at a. cost of some 68 dollars, they straightened it out. Tony understood that Janet had met the ball player only once at a benefit show, after which they’d had dinner together with other people; that the ball player, being engaged to another girl, was just as upset over the columnists “wild item” as they were. Janet, in turn, satisfied herself that Tony really believed that she loved him, and only him. And that morning, before they went to sleep in cities thousands of miles apart, they agreed to advance the date of their marriage by several months.

All this made the MODERN SCREEN correspondent a happy man. He was able to let his editor in on the news six weeks in advance, because he was with Tony at the time. Net result: several other magazines appeared on the newsstands with stories about Janet’s “new” romance, and her ditching of the actor for the ball player, at almost the precise time she became Mrs. Tony Curtis.

Today, Janet remembers this experience, along with a few others, from an equally mature though feminine viewpoint: “I have a reputation for never forgetting anything, and those hectic days left a deep impression. The things that were printed sometimes! It was all publicity—Tony loved somebody else. I loved somebody else. Every few days we’d read how we’d split up—sometimes even by the same writer who’d said we’d never gone together in the first place. I don’t care what anyone says; that’s not funny when you have to live through it, and it’s not an ideal beginning for marriage.

“But we survived all that. We did get Married, and even when some people wouldn’t leave us alone, we learned not to get nervous about rumor any more. We learned to live our lives and let other people say what they liked, hoping as we still do that maybe they’ll eventually give up and go away.”

Unfortunately, Janet knows that this will never happen. During their two years together, they have observed an even dozen famous marriages crack up. They know that reporters, although they are a frequent irritant, are not really to blame. The truth is, as Tony puts it, “Movie stars have the same right to fall in love as anyone else.” They also have the same right to fall out of love, and like human beings everywhere, they will deny, up to the last minute, even to themselves, that a romance or a marriage is really over. That’s why the whole marriage picture in Hollywood has become a strange game in which reporters must use every clue and device known to journalism in order to pass on to their readers the facts and trends in each matrimonial situation.

Sometimes (but not too often) they can be dead wrong. For instance, not many evenings ago, a guest at a Hollywood party, seeing Tony going through the hilarious fun of the magic acts he learned for his part in Houdini, asked where Janet was.

“Oh,” he was told, “she was tired, so she went home.”

A few days later a columnist hinted that Janet was fed up with Tony’s preoccupation with magic, toy trains, and such-like. Net result: They were having serious trouble. This half-truth could have started a fight between Tony and Janet.

No such thing happened, and this is why: “Of course we have fights,” Janet admits, “but for one simple reason. It’s the things we worry about in each other. That sounds a little Pollyanna-ish, but that’s how it is. I’m a busy person. So is Tony. The difference is that I’m not a very good sit-stiller. For instance, Tony is one of those people who can sleep 15 hours if he has 15 hours to sleep in, If I get eight, I’m lucky. Six is my average. When I get up, I have to get busy.

“That gets Tony mad. Starts a health lecture. He’s so good at it he could take his solemn warnings out on tour. Then, he makes me mad when he forgets to get a haircut, or starts out somewhere, dressed more or less formally, in blue jeans and T shirt. Tony’s not sloppy, but he’s not what you call clothes conscious, either. (The truth is he started out to be, but so many people razzed his selection of clothes that he decided to skip the whole thing.) Once or twice I’ve caught him ready to go to a party looking like a man who’s just been wrestling with a mountain lion.

“Don’t misinterpret this, now. Objectively speaking, I don’t think that’s good for people in our business. Everyone’s got a certain thing to sell, I don’t care what they do. Part of ours in the movie business is appearance—perhaps a kind of personality by which you become known. Sometimes even talent, if you happen to have it. But appearance, certainly. Naturally, it works the other way sometimes. You want a switch? Here’s one. Sometimes Tony catches me looking a trifle goonish. So it’s back to the mirror for Mrs. Curtis until Mr. Curtis approves.

“Mostly, from what I have learned so far, I think it’s a good idea for one person to leave another’s personality and habit patterns alone, and not to intrude on his individuality. But with Tony I do reserve one right—not to be penalized for speaking my mind if I think it should be spoken. I don’t say he has to act upon my ideas; I do insist on the right to express them. He feels the same, and that mutual attitude has saved us a lot of serious trouble.”

Few Hollywood people have the courage or even the sense to express themselves in such an honest evaluation of themselves and their marriage. It must be increasingly apparent that Janet Leigh not only knows her way around the English language, but doesn’t use it to lie to herself.

“Of course,” she continues, “there are a lot of little things. I worry about Tony’s not eating enough. On the other hand, he’s afraid I’ll go up like a land mine some day, after one too many desserts. I fix him four eggs for breakfast and stand over him until he’s eaten them. He groans, complaining that food is just an ordeal, a chore to get over. Then, Tony likes a room hot; I like it cool. He goes around the place turning up the heat. I follow him, turning it down. He won’t ride with me in a car. He’s got to drive.”

Right here, Janet is speaking of the type of little problems which, when all strung together, can begin the breakup of a marriage. Usually, when Hollywood marriages break up, the publicity releases make the whole thing sound like some horrid freak of fate played upon two perfect people, instead of the truth. The truth? Well, it gets back to such things as a husband not liking to have four eggs crammed down his throat each morning by an ever-loving spouse. Then a whole series of minor irritations which are climaxed by a full-blown physical and spiritual parting of the ways.

That this doesn’t happen with them, or hasn’t yet, is best explained by Janet.

“In two years our marriage has mellowed. It’s sort of shaken down. We’re in a groove now. A groove, I said—not a rut—and we’re better people for it, I think. Happiness is always happiness, but it may be more assured happiness because of time. I’d wish that to everybody. Our feeling for each other has deepened, and if the deepening robs the intensity a little, then that’s a healthy form of theft. You can’t hold a melting-eyed closeup indefinitely, and you aren’t expected to.”

At this point, having gallantly given the wife the first words, Tony’s attitude is pertinent, if at times contradictory.

“This marriage is wonderful, no matter what you may read,” he says. “It gets better and better. Janet and I aren’t exactly of high school age any more. We’re growing up and learning something new about each other every day. You grow up. You’ve got to. Everything in your life comes of age sometime. You discover that your work belongs to your marriage. Your marriage belongs to your work and your social life, and so on. In the long run, you can’t disunite anything without tearing yourselves apart. Take this acting. I figure that with each picture I learn something, I get a little better. If one isn’t so good, I learn from it. I gain in confidence and I take that confidence home to the marriage. It must be the same in every business; in every household.

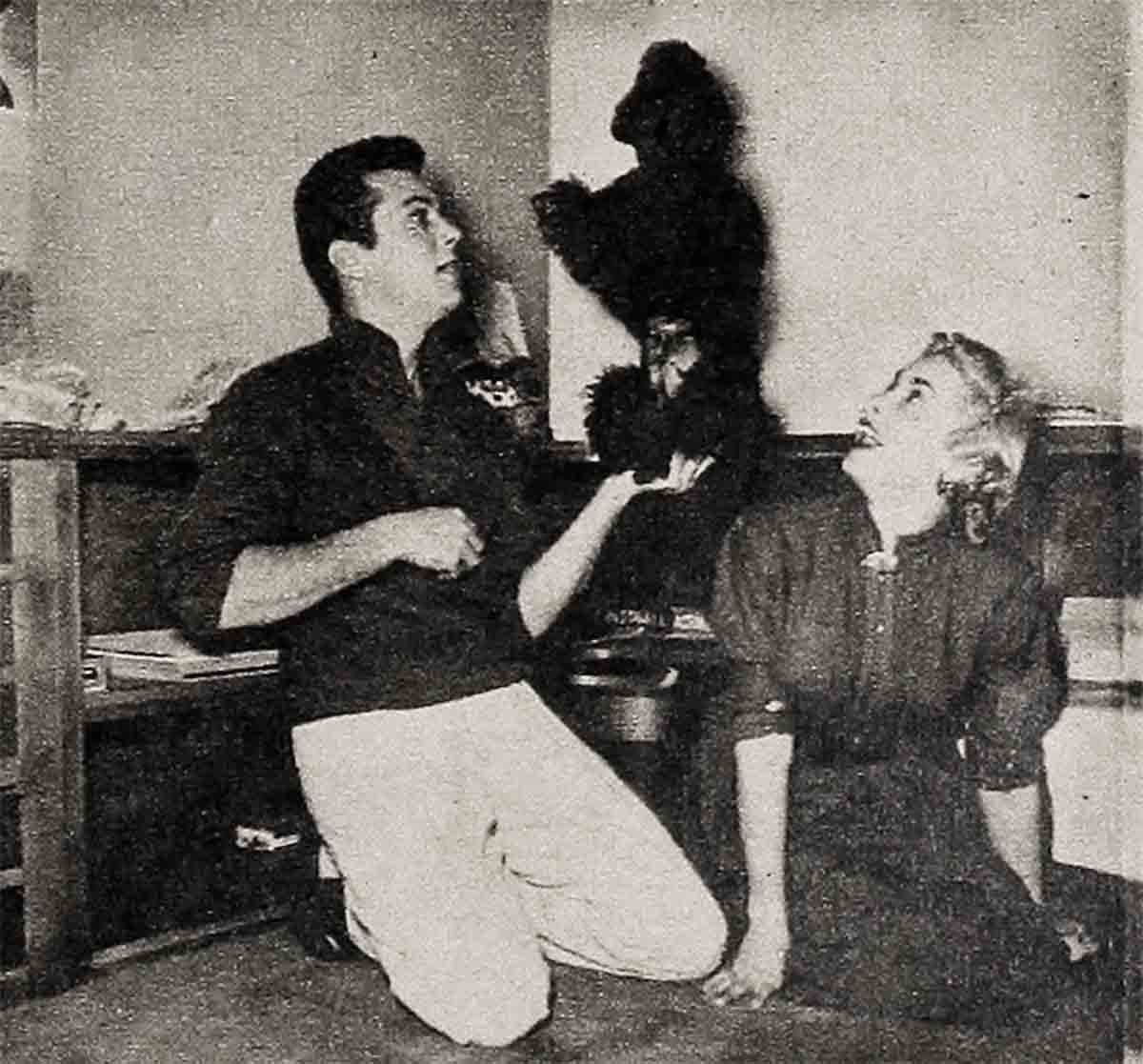

“But that doesn’t mean that you can take your work home with you. Brother, that’s murder. Many a happy home has been wrecked by that. Look, I come home, I got hobbies. I got this model boat I’m building. I got a tape recorder Jerry Lewis bought me, 900 bucks’ worth. I got a camera I’m learning to work, got an electric train, even. To explain, when I go home of an evening, I may go to work on my boat. I work with parts that are a 16th of an inch ora 32nd of an inch—all small and delicate—putting in pieces you can hardly see. And while I’m doing it I’m thinking about that work and nothing else. I’m just another guy with a hobby. I’m not telling my wife, actor-like, about how the director just doesn’t have the “savvy.” I’m not fighting with her. I’m just fooling around, relaxing with a gadget that cost $1.90. Maybe some other people are spending $30 an hour going to a psychiatrist to find out why their wives get on their nerves, or vice versa. That’s not for us.”

Both Janet and Tony feel that the “Gee Whiz Kids” part of their marriage is over. Thinking back on it, they may wonder, sometimes, whether the public ever thought they were a real couple, or a pair of fiction characters put together from a chocolate éclair recipe.

“We were and are real, all right,” Tony continues. “Almost everything written about us has been true, outside of the ‘pan’ gossip, and if were not quite so romantic to read about now, we’re at least more plausible. I think we got that way by going over the hurdles. Some of the people here in Hollywood, they got a cute custom. Cute like a hit in the head. When we were first married, we discovered these goons. I don’t want to make it too nasty, but at parties and other places they make a deliberate effort to cut you apart.

“Maybe it’s nothing worse than a sophisticated form of needling or a practical joke. But it’s a fact that somebody will make a pass at the husband, and somebody else will make a pass at the wife. Then they like to sit back and laugh when the trouble starts. We went through it, but we discovered that when nothing happens they’ll leave you alone. I’ve had it—up to here, and when you’re in love it’s not pleasant. Now that we’re an old couple, I guess we’re immune, and I must say I don’t miss this sort of indoor sport.”

Here, Tony Curtis has put an expert finger on the trouble with many Hollywood marriages. Frequently it’s not a matter of what happens at home as what happens away from home that leads a movie couple down the road of disenchantment to divorce.

Janet has an excellent slant on this observation. “We’re relaxing now—I mean both in a social way and with each other. That must be the growing up stage. In the first year everything the other wanted was just ‘ducky.’ If I wanted to go to the movies, so did Tony. If Tony wanted to stay home, Janet was all for it. Never a disagreement; a state of affairs which, if it had gone on and on that way, might have brought on an interesting psychological condition.

“Then, just the other night we were scheduled to go to some party or other. All of a sudden I turned to Tony and said, ‘You know, I don’t want to go.’ And do you know what he did? He laughed. He threw back his head and laughed in the most relieved sort of way. Just this side of mild hysteria, he said, ‘Janet, that’s the first time I’ve heard you declare an honest impulse since our courtin’ days.’ He didn’t want to go either. It turned out we were both going to go because we thought the other wanted to. It was a great discovery to make about each other, and it’s making life a lot easier.”

On this note, the bittersweet recollections of Mr. and Mrs. Tony Curtis cease, but further cursory research discloses that the Curtis marriage, however sane and intelligent it may now be, was not without flamboyance in its earlier stages. It took place, as much of the civilized world still remembers, on June 4, 1951, at the Pickwick Arms Hotel in Greenwich, Conn., and amounted in effect to an elopement right from under the eyes of the stockholders and studio brass, an executive group opposed to the whole foolish business.

Tony’s best friend Jerry Lewis had to relay to the pair the displeasure of their various employers over the whole proposition. Lewis was in favor of love himself, but had agreed to state the executive attitude formally, the executive attitude being that marital status would detract from the boxoffice impact of both partners. To their everlasting credit, the two embraced the general state of mind of General McCauliffe at Bastogne and went ahead with their plans.

As it turned out, there wasn’t so much of a flap after all. No known suicides followed the revelation that Mr. Curtis was no longer a nominee, and Mrs. Curtis’ following held up equally well.

Miss Leigh, according to the soundest available sources, is a protegée of Norma Shearer, who came across her at Sun Valley and rushed the news to Hollywood. Mr. Curtis, whose great-grandfather was a seven-foot-eight strong man in a Budapest circus, is the protegé of every woman in America under the age of 23. He himself will be 28 the day before his second wedding anniversary, on June 3.

So ends another interim report on the Curtis family, as they step up from the role of America’s sweethearts to the more recognizable grade of a devoted married couple, a little older and a little wiser, if still not quite ready to renounce sugar, spice and similar ingredients.

THE END

—BY ARTHUR L. CHARLES

(Janet’s latest film is MGM’s Confidentially Connie. And both Tony and Janet are in Paramount’s Houdini.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1953

No Comments