An Exclusive Protest By Vaughn Meader

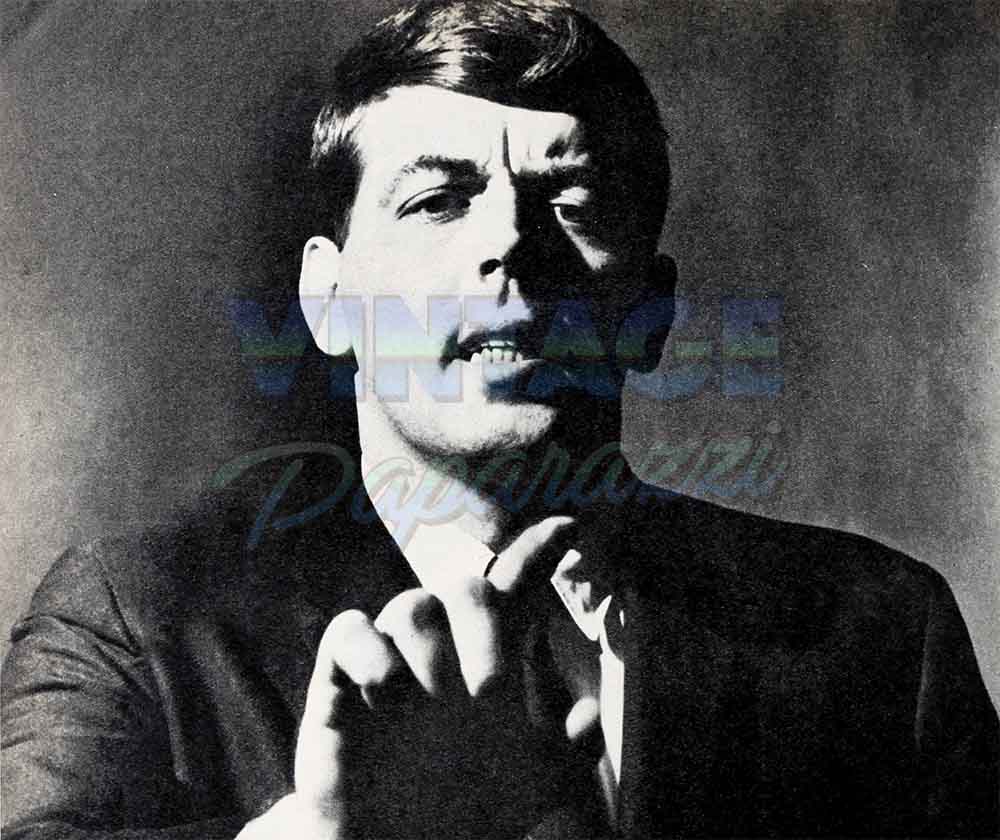

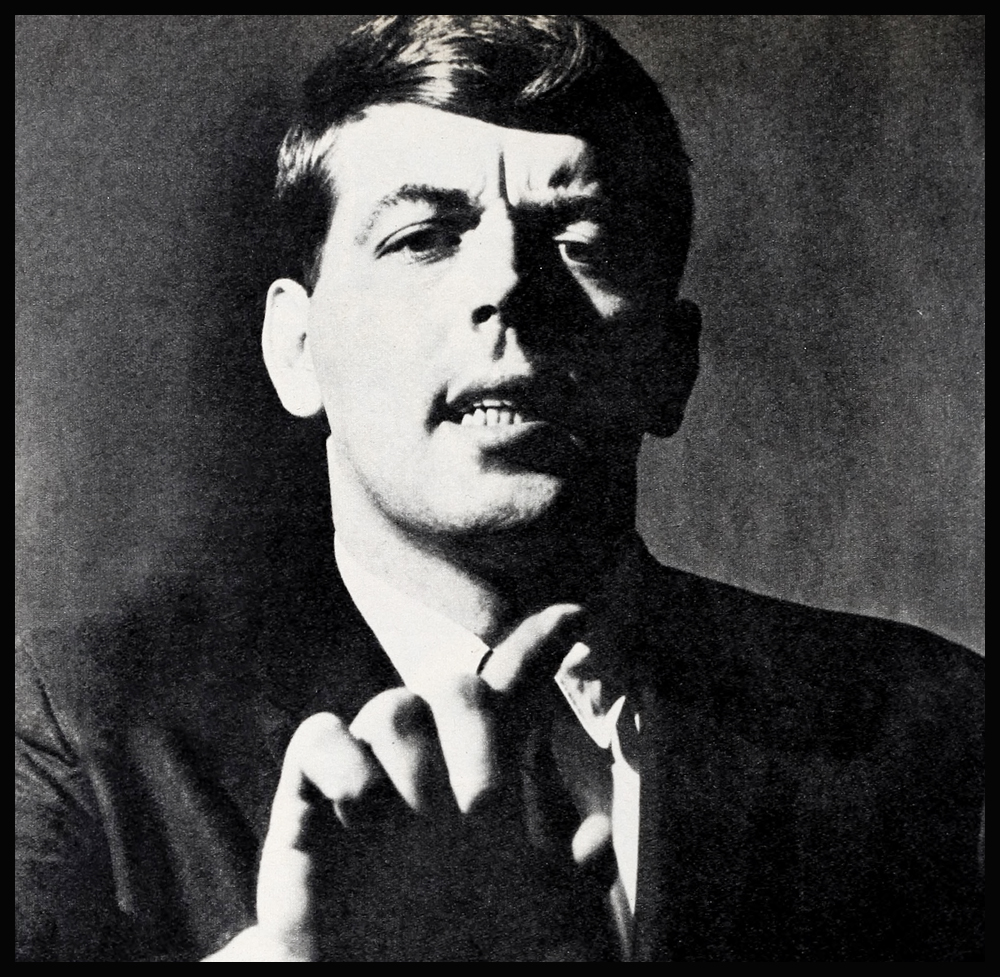

Vaughn Meader. Show biz phenomenon. Already a legend. Young man with a head of hair as unruly as the President’s. Has become, in a few months’ time, the hottest thing in the business. Can make his voice sound more like JFK than JFK himself. (“I wish Mr. Kennedy would stop imitating me!”) Young impersonator-comedian-singer-actor who will go down in history as star of “The First Family,” that hilarious spoof on Jack, Jackie, Caroline and their colleagues—the fastest-and-best-selling record album of all time. Twenty-six years old. Five foot eleven. A strangely thin hundred and eighty pounds. Brown eyes. Brown hair. Born in a tiny, unimpressive apartment in Boston’s Back Bay section. Still lives in a tiny, unimpressive apartment in New York City’s unfashionable Yorkville area. Young man with a sad past but a sensational present. Future uncertain. Funny man. Serious man. Interesting man. All man. Lots of men rolled into one. Vaughn Meader is the name.

Come meet him with us . . .

It’s a Saturday night. The place: Baltimore— backstage at the mammoth and ultra-new Civic Center Arena. The time, 8:20—ten minutes to show time. “The First Family” company is about to play performance No. 24 of a grueling tour that is taking them to fifty different cities in just about as many nights. They should all be pooped by now, but they’re not. The tour is a success. The customers have been flocking in. There’s cash in the air. And anticipation, too—everyone looking forward to the finale at the Sahara in Las Vegas, where Vaughn and company reportedly will earn $22,500 a week for three or four weeks. There’s lots of good stuff in the air—so who’s tired?

Except Vaughn. He looks tired. The burden of the whole show is on him. And they never let him be. Fans beg for autographs. People mill around him, staring. “Gee, yeah, he does look like President Kennedy.” Newspaper reporters in every city grab hold of him with their questions. The interminable round of TV and radio interviews goes on. Tiring business. A nice, profitable way to get tired—sure. But tiring business nonetheless.

And so when we poke our way into his dressing room at 8:20 and ask, “Would you like us to hold off on you for a little while?” Vaughn yawns a mock yawn, smiles and says, “Yep, if you don’t mind.” Then he makes a suggestion. “Why don’t you talk to some of the others in the show first? They’ll tell you what kind of a rat I am. Then you get back to me at intermission and I’ll tell you how wrong they are.” He smiles again. “Okay?”

Suddenly we feel a little spooky about all this. Vaughn has been getting into his costume (an expensive looking tuxedo), and in makeup, and damned if he doesn’t look like the President of the United States. We resist the urge to say, “Yes sir.” We manage a smile and a quick, “Okay,” and we’re off to talk to the people who know him.

First stop: Dressing Room No. 2. We knock. Jacqueline Kennedy opens the door. Oops, sorry! It’s Naomi Brossart, who plays Jackie in the show. A tall girl. Twenty-four years old. Three years out of her hometown, Mt. Prospect, Illinois. Vividly pretty. Short cropped light-brown hair under that First Lady wig (as we find out later). Elegant-looking as they come. She’s wearing a white sheath gown straight from an Igor Cassini drawing board—it looks. Very, very elegant. Until we mention where we’re from. That’s when our First Lady look-a-like breaks up and shrieks, “Oh golleeee, I’ve always wanted to be in PHOTOPLAY! I mean it!” Obviously, she really meant it.

We chat with Naomi for a while, about her ambitions: TV, Hollywood, stardom, the big dream coming true. Then the talk turns to Vaughn and she says, “He’s a quiet fellow, real quiet. I met him a few times when I was trying out for the record—and always, Vaughn would be the fellow sitting in the corner, just listening to me, never saying a word. Then one day—I still didn’t have the part—he got up and came over to me and told me that Jackie would never say ‘tehr-riffic,’ the way I’d just said it, she would say ‘t’riffic.’ And I thought to myself, ‘Why, yeah, that’s right.’ And then I thought, ‘I don’t know who you are, sir, but thanks a lot.’

“Well, a few days later, I’m sitting at my desk—I was a receptionist for the Playtex people, girdle division—and I get this call saying I’ve got the part. I nearly flipped for joy. Then I thought about this fellow who’d helped me with ‘t’riffic’ and a few other words, and I wanted to hug him in gratitude. I had no idea he was Vaughn Meader. When I got to the first rehearsal and we were officially introduced there wasn’t even any time for a hug. We got down to work, right away. And it was amazing, but as Vaughn read his lines, his voice was so like the President’s that I felt a terrible responsibility to do my part precisely right. And I felt so inadequate. It’s a tough job, imitating Jackie’s voice. Basically it’s a boring voice, and so I have to caricaturize it to get any good effects. But Vaughn’s interpretation of the President’s voice, I saw right away that first time, was not a caricature, but John F. Kennedy’s voice—but precisely. And amazingly.

“Vaughn was very relaxed the day we actually made the recording. Before we started, he sat at a piano and played away. He’s always playing the piano. He’s very good at it, too. So that day he’s playing away and he begins to sing. And I walk over to him and say, ‘Why don’t you sing like Kennedy?’ He says, ‘Yep’—and he does. Then I begin to sing along with him, like Jackie. And the producer heard us and laughed, and that’s how we got the ‘Auld Lang Syne’ bit into the record. But I’m afraid it was my only contribution to the material.

“That day we cut the record was the first time I met Vera, Vaughn’s wife. She came in on her lunch hour, I remember, and she sat there, very quiet. Very sweet. They have such a beautiful love story—how they struggled together these past six or seven years, how Vera supported Vaughn. It’s funny about Vera, but it seems that with all this success of Vaughn’s she’s become even more quiet and withdrawn recently. It’s understandable; at least to me it is. All this sudden fuss and everything. And Vaughn is so kind with his wife—the way he always tries to make her comfortable and the way he always takes her along to wherever he’s going. To me it’s just a beautiful love story—two shy and lovely people who worked so hard together and who now kind of hold each other’s hand as everything is happening all around them. Oh yes, Vaughn is very shy, I think. And the way he’s overcome his shyness is to sing and play piano and get into this business and, especially, to do impersonations of other people.

“Like with me. I’m shy, too. I used to be an outcast in high school. Because I tried to be a clown. And people would say to me, ‘Don’t act like that—it’s not ladylike.’ But so many of them didn’t understand that the way I was trying to overcome my shyness was by being funny. Jacqueline Kennedy is shy. My gosh, that’s the very basis of her appeal. She speaks so softly, like this—shhhhhh hel-lo Mr. De-Gaulle—she speaks so softly because she’s afraid. And shy. Just like everybody.

“I see Vaughn Meader as I saw him before—quiet, fine, a fine human being inside. He hasn’t let any of this thing, this quick success, go to his head. A lot of people would go crazy with this kind of thing. But not Vaughn. He’s too for real. He’s too genuine. They don’t make them like him just any old day.”

Our next stop: Dressing Room No. 3. We knock and an adorable-looking little girl, Jan Rhodes (the Caroline of the troup), opens the door. Jan—who’s got about as many TV and stage credits as the real Caroline has ponies—giggles something about the fact that she’s just taken a shower and we should excuse her if she goes on drying her hair. And then she says, Still giggling. “Mr. Meader always calls me Chubby. That’s my nickname. Oh, he’s so nice. Even when I gave him a hard time he was so nice. It happened the other night. We were playing Bridgeport. And I found this Italian restaurant where they make my favorite dish of all—spaghetti with oil and loads and loads of garlic. Well, I had to tell Mr. Meader before our big scene—the one where he leans over me and tells me the bedtime story— I had to tell him that I smelled pretty bad. But he just took a good whiff of me, screwed up his nose a little and then he said, ‘Oh, that’s all right, Chubby. I like garlic. I love garlic. I’m crazy about garlic!’ Of course I knew he was lying. I knew it bothered him just like it would have bothered anybody else. But he didn’t let on. And see what I mean, how nice he is? . . . He’s nice to everybody. He’s a very nice man. He’s not like some other people in this business, who aren’t nice at all. I want to give Mr. Meader a present when we end our run. Something real special. What’s that?—has he ever given me a present? Hmmmmmm, we’ll see on my j birthday. I’ll be eleven the twenty-third i of this month—and we’ll just see.”

It’s 8:30 by now. The show has begun. Vaughn’s still in his dressing room, resting, he’s not due on stage for half an hour yet. Outside his door, two men stand talking. One is Buddy Allen, Vaughn’s manager. The other is Dick O’Neill, actor.

Dick says, laughing, “He’s a good poker play er. I can testify to that. We play to- gether once in a while. It’s one of the few ways the poor guy can relax nowadays.” Then, not laughing. “It’s not easy being the biggest thing in the business all of a sudden. The pressures are pretty tremendous. And to make it all worse—some of the creeps that Vaughn has to put up with! Last night we were in Norfolk at the Key Club, just sitting at a table minding our own business. And this guy comes walking over to the table, stares at Vaughn and calls out to someone, ‘You know who this screwball is? Vaughn Monroe!’ And then, a few minutes later, a girl comes over and she says to Vaughn, ‘Oh, would you please say “great vig-ah” for me?’ And Vaughn says to the girl, ‘Would you like to write some shorthand for me?’ The girl says, ‘What? I don’t get it.’ And Vaughn says, ‘Well, you do your work and I’ll be happy to do mine.’ The girl says hmphh and walks away highly insulted. . . Funny how the truth can hurt, isn’t it? And Vaughn, while he doesn’t mean to hurt anybody—he’s certainly truthful.”

Says Buddy Allen, the agent, next: “Nobody in the business has ever risen faster than Vaughn. It’s an incredible story, but true—the guy who had nothing to the guy who’s got the world at his feet. The day the record was made to the day it sold its four-millionth copy—those were eight weeks that shook the world.

“The first time I saw Vaughn perform? One night last May. I had a few hours to spare this night. I went over to a workshop where comics work out. I watched one comic after another, and there was only one who interested me—Vaughn. He did a little Kennedy that night, not much; but what really interested me was that his stuff was high-level and full of imaginative satire—and that he wrote his own material. I didn’t approach him that night.

I went home and I thought about him for a while. Then, a couple of days later I went down to this place in the Village where he’d picked up a small job. And by now, seeing him work in front of an audience, I was convinced that he had it, really had it. And I signed him.

“I’ve got to say two things about Vaughn. One—that he’s got a lot more talent than just as an impersonator, and that in short time he’s going to prove that this is not a flash in the pan. Two—I think that for a young boy who has had such instantaneous success and such a fantastic thing happen to him, I think he’s handling it very well. I’ve been around this business a long time. I’ve gotten to know that success is a lot more difficult to handle than failure. I’ve seen people actually go berserk with power when they’ve become successful. But not Vaughn. Not our boy.

“I’ll never forget it, that night we opened at Carnegie Hail. It was a one-night date. It was an important night. Then the newspaper strike came along and threatened to make the whole thing a shambles. There were lots of people who suggested to Vaughn that he cancel out. They told him, ‘You’ll be lucky if half the house is filled—it’ll look bad to any of the important people who happen to be there.’ As it turned out, these suggesters were all wrong, because we turned the customers away that night. Anyway, they didn’t know who they were talking to, these people. Because if you say something to Vaughn that he doesn’t agree with, you’ve got a tough fight on your hands. And what he’d answer was, ‘I’ve got a deep respect for the public. I’ve got a commitment to the public. Even if there are only one hundred customers out there, I’ve got to show up in front of them and give them everything I’ve got.’

“I think that to Vaughn, the audience stands for a family he finally belongs to. He loves those people out there. And he’s grateful for being loved back by them. He had a very rough childhood. His father died when he was an infant. His mom had to send him off to Maine to live with some people while she worked as a waitress down in Boston. He had nobody, not for a long, long time. Not until Vera came along. And now the audiences. . . . Have you met Vera yet? No? Well, you’ve got to. She’s around tonight. Meanwhile come on, I want you to meet some of the other people who can tell you a little bit about Vaughn.”

First Buddy introduces us to a young Brooklyn-born comedian, one Stanley Myron Handelman. And Stanley says to us, “Vaughn and I first met down on Bleecker Street, at a little club where we worked. What we did? Well, we made audience for each other because usually nobody else was there. We got fantastic money, too. I had more lines than Vaughn, so I was getting $8 a night, whenever we worked. Vaughn had less lines so he only got $7 a night. This club is a place where a lot of comedians go to break in material. It’s pretty depressing at a place like that—because you get to see how much nontalent there is around. But Vaughn and I were talented, I like to think. In fact, we revered each other. Revered. He thought I was pretty funny. For instance he said to me once, ‘That’s some name you’ve got there—Stanley Myron Handelman. Is that your real name?’ And I said, ‘No, oh no, my real name is Sheldon Lewis Engelberg.’ And Vaughn laughed at that. Yeah, he laughed, so I knew I had an appreciative friend.

“As far as his talent goes, I thought it was very contemporary, that it had a great appeal to people looking for something outside of Catskill Mountains comedy—you know, the guys who get up there with the fast delivery, the yak after yak routines, the machines who just get up there and grind out one joke after another. But Vaughn’s humor was very serious, and very well thought out—and extremely dry and New England.

“Anyway, we weren’t at the Bleecker Street club for long. Like I said, not too many customers.. And one night we shook hands, said goodbye and went our separate ways. I had no idea where Vaughn was going from there. But I sure knew where I was going. Right up to the Catskills where I’d taken a job as athletic director at a resort. What a place that was. It was like the age group was from ninety years up. My biggest job was to organize sitting-around-the-pool tournaments. But Eve got to say, we didn’t have one accident. I mean, how hurt can a person get falling off a chair? Even a ninety-year-old person? . . . So anyway, there I am, big athletic director doing nothing. And one night all my clients are fast asleep—by seven o’clock they’re sleeping, all right—and me, big roue that I am, Em sitting up and watching television and I saw the “Talent Scouts” show this night and there’s Vaughn, fresh out of the Village, being introduced as a new and hopeful discovery. And then Vaughn began to make it so big in night clubs that the ‘Talent Scout’ people asked him to appear again. This time he was to introduce a new talent—and Vaughn thought of me. He phoned me one night and he asked if he could do the honors. Yeah, ever since then, things have been going very nice for me. Eve been on the Merv Griffin show. Em with this tour now. “My appreciation to Vaughn? Let me put it this way. I had decided for a while there to maybe quit the business and go back to Brooklyn and be a school teacher. And all I can say is that Vaughn Meader, by giving me a break, saved a lot of little, unsuspecting kids from a terrible fate!”

Next we’re introduced to Michael Ross—writer, actor, comic and now director of the “First Family” tour—who says to us about Vaughn: “He’s a reticent boy. He does not open up to people easily. But once he does, he’s quite the opposite. And he begins to speak as if his thoughts are ahead of his words—a kind of shorthand way of talking—and he expects you to know just what he means. Vaughn is quite a complex person. He works on a great deal of nervous tension. His true humor is very biting. There is a kind of doggedness about him and a desire to learn, as well as a great need to work and to play. Complex, as I say. But if he’s got his own little devils inside of him—well, he’s entitled to them. He is, to me, a boy of terribly good taste. He’s a good boy, and he will not do things that vaguely resemble anything shoddy. It’s a natural thing with him, this matter of taste. Not something that he’s learned, or is learning. He’s in a strange position now. I can infer by everything he says to me that while he is enjoying his huge success right now, the success is not as important to him as tenure. He knows that the Kennedy thing can’t last forever. He knows it’s a gimmick, an attention-getter. And he knows darned well that after the gimmick wears off. he’d better start doing something else.

“What’s that? Do I think the talent is there? Yes, I do. Else I wouldn’t even be talking to you about Vaughn Meader right now. I think he has good musical talent. I think he has good dramatic talent. And, to me, his greatest talent of all is his mind, his brain, his wit, his quickness. Why don’t you step backstage right now and see what I mean? Vaughn’s on by now (checks his watch) yes, he’s on now, doing the press conference-routine. It’s totally unrehearsed. He stands there, alone, as the President, and asks for questions from the audience. Some of the questions are lulus. And so are Vaughn’s answers. He makes it look quite easy. But really it isn’t. You’ll see what I mean.”

And we do. A few moments later. We stand there in the wings, listening to the questions being hurled at Vaughn one-two-three, and Vaughn’s rapid-fire repartee:

“Mr. Kennedy, who do you think will be the next President?”

“Why? I don’t plan to go—er—anywhere.”

“Whatever happened to Vice President Johnson, Mr. Kennedy?”

“He’s lost—which is pretty easy to do down in Texas.”

“What’s the matter with Senator Goldwater ?”

“Well, let’s start with his name—”

“How is Adlai doing?”

“I need him. He is so brilliant. I need him to help Teddy cross the streets.”

“Mr. Kennedy—how do you and your wife feel about birth control?”

“We believe in separate vacations.”

“Is there any truth to the rumor that you I were married once before?”

“Em glad, hmmmm, yes, that finally Confidential Magazine sent a representative here!”

And so it goes, each of Vaughn’s lines greeted by uproarious laughter. We’re laughing too by now, long and hard, when Vaughn’s agent, Buddy Allen, asks, “Would you like to meet Vera now? She’s in Vaughn’s dressing room, just sitting there.” A little reluctantly we leave the wings and follow Buddy to the dressing room.

Our reluctance fades fast as we are introduced to Vera Heller Meader—once an obscure waitress in Mannheim, Germany, now the wife of a U.S. “President”—a blond girl in her mid-twenties, short, pretty, soft-spoken as a breeze. A serious girl who does not smile as she speaks, not once, not at all. But there is an innate pleasantness about her that transcends smiling. And we begin to feel the warmth that she and Vaughn share as she starts to tell us their little story:

“He was in the Army when we met. In Germany. He worked as a soldier during the day and at night he played the piano and sang at a club where I worked on the tables. Serving. I remember the first time I talked to him was when a customer requested an American number and I went over to the piano and said, ‘A gentleman wants you to play “Sawdust.” What I really meant, of course, was ‘Stardust.’ But I didn’t know much English at the time. And Vaughn began to laugh, so much.

She’d heard about soldiers

“He liked me right from the first. And I had heard so many things about soldiers, I didn’t know whether to like him or not. But then I began to see that he was basically such a friendly guy, just a regular guy, and very kind and truthful and I began to believe in him. What I liked most was that he never would get fresh with me. We dated. He would bring me home. And that was that.

“How did he propose to me? You should ask better how many times did he propose. Because always he would ask and always I would say, ‘No, not yet, don’t ask me yet.’ I don’t know what I was waiting for. I guess I knew that marriage would mean leaving my family eventually, and our city, and I was very close to the family.

“Speaking of the family, it was very interesting with Vaughn. I could tell with most other people that he was very often uncomfortable. I could see it in his gestures, that he was not sure of anybody. I knew his childhood situation—how his father had died, how his mother had worked so hard so he could stay with people and so he could go to school and grow up properly. I knew that this lonely background perhaps caused a discomfort for him with people. But when he met my family he was right at home with my parents and my sisters and brothers. After we were married we all lived together for a while. And I could see that Vaughn just loved being with a family, a big family, at last. He never said to me he liked them. He confessed to me later that this was because he didn’t know how to tell them how much he liked them. But you could see it by what happened the day we had to leave them for the States. We were all at the railroad station and Vaughn started shaking hands with everyone and then. all of a sudden, he broke down—even more than I did—he began to cry so much, like a child. And he just looked at everybody then, and he just said one thing. He said, ‘You people have been so nice to me.’ And, by that, everybody knew that he loved them just as they loved him.

“When we got to the States it was very tough on us. We went up to Maine first and Vaughn tried farm work, but that was not for him. So we came down to New York with practically nothing. In New York for a while we stayed with a woman who had raised Vaughn part of the time when he was a boy. She took us in. She is a very kind and helpful woman whose name is Sally Fribergh. We can never forget her kindness. But we knew soon that we had to be on our own. So I got a job as a librarian. And Vaughn began looking for work as a comic or m.c.—work which rarely seemed to come, so once in a while he would take any kind of job. Like one time he worked in the shipping department of the S. Klein discount store on 14th Street. Things like that.

“We took a furnished room for a while—$10 a week—it was really terrible—dirty, with lots of mouses always running all over. Until finally we got our little apartment, two and half rooms in the German section of New York, where at least I could feel a little more at home. Vaughn continued looking for work, and sometimes he talked about a big break maybe. And I would not know what to say—because, well, I was not yet enough used to America, where the big breaks really seem to happen sometimes.

“And then, as you know, the big break did come. And oh, I don’t know, but it’s all been so much since then. People are always curious to know how I react to all that has happened these past few months. They ask me questions like, ‘How are you and Vaughn treating yourselves to all the things you’ve always wanted?’ And I can only say to them that it all came so quick, that there hasn’t been the time to treat ourselves to anything new or special. It is strange about things like this, no? I mean when Vaughn and I were so broke and never had a dime, there was always food in our icebox. And now, you look in the icebox and you will not even find a drop of milk. There’s no time to eat, anymore.”

The door to the dressing room opens suddenly. Vaughn walks in, Still tired-looking but smiling. It’s intermission time, Part I of “The First Family” is over, the sound of applause is right behind him.

He closes the door, walks over to Vera, kisses her on the hair, then sits and talks for a while with us as he unwinds.

Then he pauses for a moment and says to us, “You’ve been talking to so many people about me. Do you still have any questions left for me to answer?”

“A few,” we say.

“Like?”

“Like do you feel you’ve changed any these past few months?”

“Yes,” Vaughn says. “I’m calmer. I’m more secure. I’m not as frustrated and nervous as I used to be. And I don’t jump so quick anymore if somebody touches me, or knocks on the door.”

“Who’s the person to whom you owe the most?” we ask next.

“My wife here. Vera,” he says. “She supported me. She worked around the clock—at her job and at home. While I waited around for work so that maybe someday we could do a little switch and I could support her.”

“What was the most encouraging thing Vera ever said to you during this time?” “I’m afraid Vera’s basically a pessimist,” says Vaughn. “And the most encouraging things were the things she didn’t say. Like, ‘When are you going to amount to something?’ There were plenty of times she could have let me have it like that. But she never did.”

“Are you a pessimist, Vaughn?”

“I’m an optimist. A great big optimist. I realize now that I had no right to be optimistic. Everything was going wrong for me. Then along came this one-in-a-billion break. But I can remember, when I was working at Klein’s, every payday I’d run into Luchow’s restaurant and spend ten bucks for a meal I couldn’t afford, just to make me feel good. And I’d be sitting there eating this steak or what-have-you and I’d tell myself, ‘Boy, come the day, come the day, and I’m going to eat in restaurants like this three times a day.’ And now, well, the day has come. And I find I’m not very hungry anymore. And, basically, I still eat the same kind of stuff I always did—hamburgers, a can of beans, lots of milk. And I find that I really didn’t mind that kind of meal at all.”

“Vaughn, more than a few people have talked to us about your desire for tenure in show Business—” we start.

“They talk right,” Vaughn interrupts. “I do want tenure. This flash in the pan business isn’t for me, not if I can help it. I know—there are people around who say, ‘He can do JFK and that’s all he can do.’ Well, to me that’s like saying Sophie Tucker can only sing ‘Some One Of These Days.’ I can do more than impersonate the President. And I want to show what I can do. And I’m not going to wait!”

There’s a knock on the door.

“Vaughn,” a voice calls out, “we’re ready for Part 2. Half a minute.”

In even less time than that, Vaughn is gone . . . headed back for the huge Baltimore stage, with Scranton, Pa., lined up for tomorrow night . . . Miami the night after . . . other cities . . . then Vegas . . . then new worlds to conquer. And possibly—and very probably—enduring stardom.

—PHILIP POPE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1963