If You Love Judy Garland . . .

All of her life, Judy Garland wanted what most girls want. But most girls get it more easily than Judy did.

“I’ve been married before, you know,” said Judy, “But neither Dave (Rose) nor Vincente (Minnelli) ever gave me an engagement ring. I don’t know why. They just didn’t.

“But I’ve always dreamed somebody would give me one, ever since I was a little girl. And when Sid said he had a little ‘thing’ for me and slipped the ring on my finger, I just cried. I really did. Honestly, Sid’s the most thoughtful guy!”

So on the second anniversary of her third marriage, Judy Garland received her diamond engagement ring and her girlish wish was fulfilled. Judy and Sid Luft had celebrated this anniversary with a party at the Mocambo. After the festivities were over, Judy and Sid climbed into their Cadillac convertible and Sid drove to their picturesque new four-acre estate in Holmby Hills. There, in the wee hours of the morning, he gave his wife the ring she had always wanted.

A few weeks before their anniversary, Judy and Sid had been down in Palm Springs at Jimmy Van Heusen’s house with Mona Freeman and Frank Sinatra. Judy and Frank sang and sang and both couples had a wonderful time.

The next weekend, Mr. and Mrs. Luft turned up at the racetrack together. Sid was so attentive to Judy that several fans commented on his solicitude and Mervyn LeRoy, who had directed Judy in The Wizard Of Oz,remarked, ou are behaving like honeymooners!”

At Romanoff’s, Chasen’s, Sun Valley, Palm Springs, Warner Brothers studio—wherever you see Judy—chances are that Sid Luft is at her side or on his way there.

Does all this sound as if the Luft marriage might be foundering?

Of course it doesn’t. But Hollywood skeptics insist that Judy and Sid have yet to find true happiness. They tell of an incident which occurred several months ago in Holmby Hills.

“It was late at night,” one neighbor recalls, “and I heard all this screaming and yelling and shouting. I knew Mr. and Mrs. Luft were in their house. And yet I didn’t know what was causing the commotion.

“Of course it wasn’t any of my business. But the Lufts do have children, wonderful kids, and we have had robberies in this neighborhood quite a series of them. And I thought for a minute that maybe it was just a domestic quarrel. What couple doesn’t fight once in a while? But the noise seemed to be too loud for that.”

Anyway, the police were called and a prowl car whizzed up to Judy’s house. The officers knocked and Sid answered. It was a quarrel all right, he explained, but it involved one of the domestic staff. ip the incident into a marital crisis. But Judy and Sid refuse to be disturbed.

Hollywood pessimists have tried to blow up the incident into a marital crisis. But Judy and Sid refuse to be disturbed.

I used to mind all those things they wrote and said about me,” Judy admits. “But now I don’t care. I’ve found some peace of mind.”

A secretary who knows Judy well, says “The best thing that ever happened to her was Lorna. I can measure the change in Judy’s personality from the day she gave birth to that cute baby girl.

“Childbirth does many things to many women, but it settled Judy and matured her. It gave her a new set of values. It solidified Judy’s marriage and changed her outlook. She looks back on her own stormy, hectic youth, and she knows that Lorna and Liza, who is eight now, must be spared all that confusion.

“The most important thing in the world to Judy used to be Judy Garland. Now it’s her children who count. So long as they’re well and happy and she’s capable of working, she isn’t worrying about what the vise guys have to say about her, Sid or A Star Is Born.

“I remember not too long ago, someone suggested to Judy the possibility that Sid was merely using her to establish his eminence as a motion picture producer.

“In the old days, the girl would have blown her top and cried and gone off on a sleeping jag. This time she merely spoke short, sharp word that left no doubt in reporter’s mind as to what she meant. And what she meant was that he was talking through his hat.”

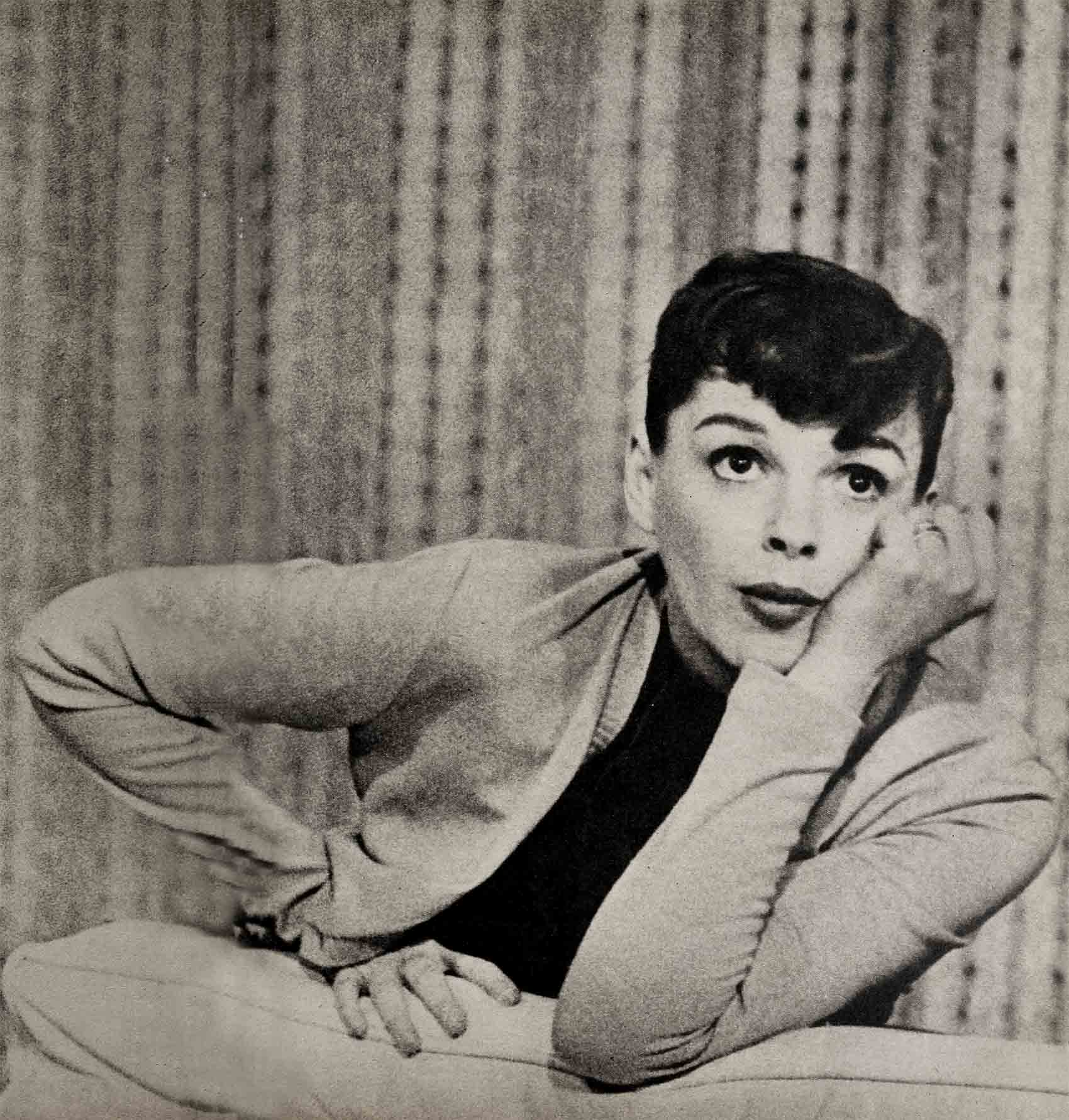

Judy Garland insists, “I am happier now than I’ve even been.” And she certainly looks it. Her weight is 110 pounds. Her luminous brown eyes are sharp and clear. Her voice is bigger, better and more controlled than ever. And she is optimistic.

Perhaps Judy has gained some confidence from her new system of periodic physical checkups. Every six months or so, she checks into the Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Hollywood and submits to a thorough examination.

After each visit to the hospital, the rumor goes around that, “Judy Garland is on that pill-kick again.” Not true.

Judy sleeps well these nights because she has found peace. How lasting it will be no one knows. Judy’s nature is volcanic and may erupt without a moment’s notice, especially if another marital disappointment were to spark the flame. But she had the strength and will power and stamina to finish A Star Is Born.

Undoubtedly you’ve heard and read about Judy and Star.

Last year when she announced that she was going to use its musical version as a screen comeback vehicle, most of Hollywood was doubtful.

“Maybe Judy will start the picture,” one producer offered, “but she’ll never finish it.”

“I don’t care what anyone says,” another executive confided. “This kid’s strung tighter than an E-string on a violin. Worse yet, her husband is producing the picture. Luft knows a lot about horses, but what does he know about pictures? You’ll hear them scrapping way off in Cucamonga.”

These were the prophecies of gloom and disaster that accompanied Judy last October when, clad in sweater, slacks, and ballet shoes, she reported to Warner Brothers for her first screen work in four hectic years.

Ii would be nice to report that everything on Star was sweetness and light. But that isn’t the way it happened.

Bad luck dogged Judy at every turn, and the fact that she could face this trouble and conquer it is what counts. At the outset, Judy offered the old Fredric March role to Cary Grant. Grant turned it down. Disappointment number one.

Then the film was begun in a photographic process called WarnerScope. After a few weeks, the photography was changed to ordinary widescreen. Disappointment number two for Judy. Then someone made another decision. “Widescreen is no good for such an important picture. Let’s switch to CinemaScope.” So all the old film was scrapped—disappointment number three—and the film was begun all over again.

With each change in photographic process, there was a Change in cameramen. Add three more disappointments for Judy.

The next trouble was with a musical arranger. So he was replaced. Then a sketch artist was sent on his way.

George Cukor, the director, began to experience a bit of difficulty. This was Cukor’s first CinemaScope picture, and he was trying to shoot it in long, sustained scenes rather than short takes. Only Judy Garland doesn’t happen to be a “long scene” actress. Never has been. She throws herself into her acting so completely that she uses up her reservoir of emotional energy very quickly.

There was one hassle after another and Judy, via the unknowing gossips, was blamed for everything.

The $5,000,000 budget, the eight months of production time and the changes in personnel were all attributed to Judy or her glands or her eating habits or her husband or her temperament or her past.

The delay and the mounting costs were attributed to every reason but the right one—that at thirty-one, after twenty-eight years of show business experience Judy Garland has developed into a mature, intelligent perfectionist who knows that in today’s market the movie-going public must be given top-flight entertainment, or the picture will flop.

“When you have your own money in an independent company,” Judy explains, “there’s a tendency to cut corners. You know, speed up everything, hire five extras instead of twenty, print the first take.

“I just refused to do that. This was my first picture since Summer Stock and I was scared stiff when I started in. I’m always scared when I begin. But I was determined to do this picture as well as possible. And I honestly feel Sid and I have.”

Asked about the reported trouble with Cary Grant and her musical arranger and George Cukor, Judy said, “There was no trouble. Just an honest difference of opinion.

“Originally we tried to get Cary for the Freddie March part. He said no, so we got Mason.

“As for my musical arranger, he kept saying during the picture that I was singing too loud. Well, I don’t have that small Movie voice any more. I’m a big girl now. I’ve been used to singing on the stage in London and New York and San Francisco. So he just quit. Otherwise, everything’s been fine.

“Go around,” she suggested. “Ask anyone on the picture. You’ll find out.”

George Cukor, a knowing and sensitive man who has directed some of Hollywood’s foremost pictures—All Quiet On The Western Front, Royal Family, Camille, The Philadelphia Story—was kind enough to explain his position just before leaving for Europe on a vacation.

“It’s amazing,” he exclaimed, “absolutely amazing how these stories get started.

“Judy was perfect in this picture. Cooperative, tireless, energetic—and I say this objectively—absolutely magnificent.

“Before the film started my friends would call me up—I guess they meant well. ‘George,’ they warned me. ‘Don’t make Star with Judy. She’s not well. She’ll hold you up. Her husband will interfere. You’ll never finish it. She’s an unhappy girl. She can’t find herself. Don’t do it.’

“Not a word they said is true. Judy is in wonderful condition both physically and mentally. And the performance she gave—well, you’ll have to see it for yourself.

“This girl has always been one of the rare, one of the truly great talents in this town. And now that talent has matured.”

A studio executive agreed heartily.

“I’ve heard so many stories about Judy Garland and Star,” he said, “that I’m sick. The plain truth is that we’re overjoyed with this picture and that Judy was marvelous all during the production.

“Sure, it took a long time and cost a lot of money, but it’s one of the finest pictures ever made. It runs more than three hours and we’re going to road-show it and Judy will probably win an Academy Award. In all my years at this studio I have never witnessed a finer performance.”

A doctor from Iowa, wandering around the Warner lot one day, had somehow stumbled onto Judy’s set.

“She was sweet and down-to-earth,” the doctor recalled. “I asked her to pose for a snapshot with me and she said, ‘Gosh! I look like death warmed over today.’ But she did pose and very graciously.”

During the production of A Star Is Born Judy might very easily have ordered a “closed set” with “no visitors” signs plastered on each door. But she wouldn’t.

“I’ve spent my whole life entertaining people,” she said. “Entertaining people makes me very happy.”

Despite this outlook and philosophy, a segment of the movie colony continues to discount Judy’s present happiness, probably because up to now Judy has had so much unhappiness in her young life.

Over the years she has suffered from poor health, unsuccessful marriages, unrequited love, basic insecurity, maternal estrangement and a fatherless adolescence. One of her old friends has said, “If I’d been put through the wringer as many times as Judy has, I’d be emotionally bankrupt and a candidate for the booby hatch.”

It is a great credit to Judy that she has survived with her courage intact.

Judy says that she “loves to work and work hard. I’ve always felt that way ever since I can remember.”

She was born in 1923 to Ethel and Frank Gumm, a pair of vaudevillians who owned a small theatre in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, at that time a town of 2,500 people.

The third of three girls, Judy was christened Frances Gumm.

She made her debut in the family theatre at the age of three. The family moved to Lancaster, California, a small desert community eight miles north of Los Angeles where her father took over management of the local theatre. Judy was enrolled in a children’s dramatics school where she learned to project her precocious voice.

Last year, a few months before Judy’s mother died—she was working in an aircraft plant at the time—she spoke of her daughter’s childhood.

“People blame me,” she said, “for all of Judy’s unhappiness. They say I deprived her of a normal youth, that I drove her into show business, that I tried to make her the big star I never was.

“That’s not true. Not a word of that is true. Even as a little girl Judy was obsessed with entertaining. She never could get enough of it.

“She always loved to sing. It wasn’t true of my other girls. But it was with Judy. She made her own youth. I let her do what would make her happy.”

When Judy was twelve an agent named Al Rosen caught her act at Lake Tahoe and took her around to MGM. The buxom child sang one song in her full-throated, uninhibited style and within a week she had a movie contract.

A month later her father died of meningitis. This was the first in Judy’s long list of heartbreaks.

Her second came at fifteen when she fell in love with a married man. Sometimes these puppy love affairs are trivial developments in a girl’s growing-up. But Judy’s first love affair was intense and important, and long after it ended, she carried a torch. Somehow her great open faith in people was irremediably damaged.

Her first marriage, to Dave Rose, was a bust, perhaps because they were both more interested in their individual careers than in their life together. The divorce left Judy with an emotional scar.

To compensate she worked harder. She starred in three great pictures, Meet Me In St. Louis, The Clock, Ziegfeld Follies.

Vincente Minnelli, aesthetic, thin-faced and artistic, offered to fill her emotional void. A year after their marriage their daughter Liza was born.

After that Judy’s great trouble started. One day she would be ecstatically happy, the next day tragically sad. One day she took pills to gain weight, the next day to reduce. One day she imbibed stimulants, the next depressants.

One doctor blamed it all on the aftermath of childbirth. MGM, the studio where she’d worked for fifteen years, suspended Judy. It looked like the end. Judy thought so, too. At twenty-seven, hopelessly mixed up, she half-heartedly attempted suicide. After that she was under a doctor’s supervision.

But all of that is part of the past. The present begins with Sid Luft.

No matter what you hear about Sid and his troubles with his ex-wife Lynn Bari, he is Judy’s perfect complement.

It was he and he alone who infused her with the desire to sing and entertain again. It was he who, with the help of the William Morris Agency, booked her into London’s Palladium, New York’s Palace, Los Angeles’ Philharmonic and San Francisco’s Curran. It was he who talked David Selznick into selling the musical rights to A Star Is Born, and it was he who helped raise the capital to form their independent company, Transcona, Inc.

It is Sid who, knowing of Judy’s old friendship with Frank Sinatra, is so understanding about having the singer visit them. Other husbands might be jealous. But not Sid. His faith in his Judy is limitless. And it should be, for these days with three children at home much of the time—Lorna, Liza and her stepson John—Judy no longer permits herself the luxury of moodiness.

“I hope to keep. working,” she asserts, “because I’ve worked since childhood and the whole pattern of my behavior would be changed too much if I were to stop.

“I do realize, however,” she adds, “that there are some things much more important than a career.”

“What, for example?”

“Children,” Judy answered. “I want more children.”

It has taken a long time, but at thirty-one Judy Garland has grown into a happy and fulfilled young woman.

THE END

—BY WILLIAM BARBOUR

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1954

No Comments