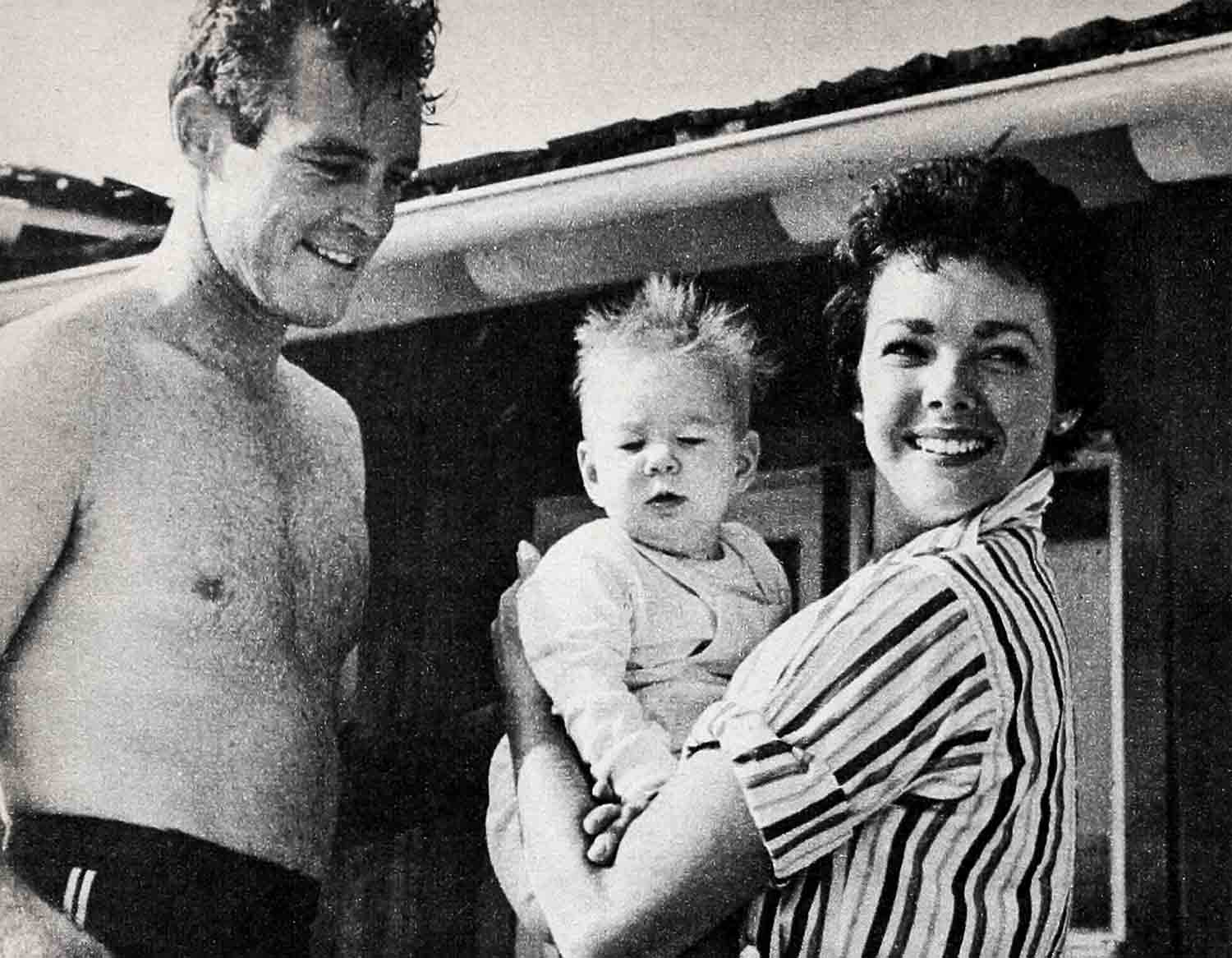

The Story Of A Happy Guy—Guy Madison

A short time ago, Guy Madison experienced one of those “moments to remember.” It began just about the way every evening begins in his life these days: Guy hurrying from the studio to the hilltop home he shares with his two dolls, Sheila and baby Bridget, and counting the blessings that are his.

Soon, he was sitting at the dinner table with his dark-eyed lovely wife Sheila. From the nursery came the faint tinkle of their daughter’s music-box playing “Brahms’ Lullaby.”

A fire crackled cheerily in the living-room fireplace, casting mellow images on the beamed ceiling and the paneled walls. Yellow tapers glowed softly in the silver candelabra. Through the glass walls, beyond the swimming pool, a city of magic danced and shimmered in the distance. And today, Guy once again has a sizable stake in that sparkle.

At a moment like this, a man like Guy Madison asks himself, out of a full and grateful heart, just what else life can possibly have in store for him.

And he was soon to learn.

“Guy, I want to go to New York to see my family,” Sheila said casually.

Envisioning how empty and how lonely the house would be, Guy didn’t want her to go “Now?” he asked. “Why don’t you wait a little while?”

“I should go now,” Sheila said.

“I wish you would wait until we’re through shooting the picture. Wait a few months, then I can go with you.”

“I can’t wait a few months,” she said, “we’re going to have a baby.”

There was, Sheila recalls laughingly, a clatter. “Guy dropped a knife or fork—I don’t remember which.”

Yes, they have that moment to remember. And more—so many more.

“I couldn’t be happier,” Guy beams, flashing the old infectious smile hat’s his again after years of heartache.

It is as though all life is a conspiracy, making up to Guy Madison for the lean years. The grim years. And deservedly so, in the opinion of those who know him and who have long respected his sincerity, his silence, his strength of purpose and spirit throughout those years.

Even for a man of action, the blessings are coming almost too fast to count. And so are the moments to remember, for Guy and Sheila, during these first years of marriage. Building and furnishing their first home. Sharing their daughter’s continual achievements—her every new tooth and every new utterance. Sharing the sentimental moments and the surprises—the many surprises—blending their own lives together.

Take their first anniversary, for example.

“I thought I was getting a gun,” Sheila recalls. “In fact, I was sure I was getting a gun. I’d heard Guy talking on the phone that morning, asking somebody if they had a certain gun. Besides, I was used to receiving gifts like guns. Once before, I’d received a set of golf clubs. And at Christmas, Guy gave me a hunting jacket like his. It’s made of lovely wool with a beaver collar. It’s a very unusual hunting jacket—a really beautiful-looking coat.”

But hardly a gift item to make a girl lose her lovely Irish head. And on their anniversary Sheila was sure she was getting the gun to go with the jacket—even when her husband arrived with an arm-load of roses and an odd-sized package guns seldom come in.

“I thought it was a strange-shaped package for a gun. But, I thought, maybe they packed it in parts. I couldn’t believe it, when I saw that white mink stole! Even now, I go to the closet at intervals, just to be sure it’s still there. It’s very stylish, too, with a high collar. The latest thing.”

Wild-game expert though he is—but unaccustomed to tracking down mink—Guy says modestly, “Well, I just checked a few. The first one I saw—well, it worked out pretty good. Sheila was surely surprised, and happily so,” he grins.

It was Guy who got the gun. was another moment.

“Sheila gave me a miniature of my elephant gun, for hunting big game. It’s all hand-made, a $400 gun,” Guy says appreciatively. “Sheila sure went to a lot of trouble getting that.”

“I saved out of my grocery money,” she says. “Not that we didn’t have enough to eat, but I cut down on desserts and things like that. I saved for months, then just when I’d get a lump sum, the milk bill or something would take it. Finally, I started putting it in the bank, knowing I wouldn’t take it out no matter what. But I couldn’t save enough. Just in time, I got a residual check for a television show I’d done, and that made it. But I felt like Scrooge for a while.”

However, Sheila isn’t always that thrifty. Take the elegant gold thoroughbred framed in the fieldstone rectangular space over the fireplace.

“That was Sheila’s idea,” observes her husband mildly. “It fits the framework perfectly. Of course, we were going to put up pictures. And a 16 mm. movie screen was going some place up there.”

Sheila got this inspiration while Guy was out of town on location. “There’s this huge gold horse for over the fireplace,” she told him one night. “We’ll talk about it when I get back home,” he said dubiously. But Sheila had already talked to. the man who was making it. Now they agree that it’s a magnificent horse—and for the fee, it should be eligible for entry in the Santa Anita Handicap.

Then there was the day Victor—an awkward shaggy dog, large of heart and frame—arrived to make his home with them.

“We’d just moved into the house,” Sheila recalls. “There was no fence or anything. Guy was going to Florida on location for ‘On the Threshold of Space,’ and he thought I should have the dog for protection while he was away.” Another dog, that is, not having too much faith in the protective value of Bijou, Sheila’s French poodle.

One day,.Guy told Sheila enthusiastically that he’d found an Airedale. “It’s just a pup,” he said. Whereupon, says Sheila, “Guy came home with this big monster. He took off for Florida, and the dog cried all night long. It missed its brothers and sisters. He was supposed to be protecting me, but I had to bring him into the house and put him in our bedroom—on our brand-new carpets—to keep him from crying.”

The following day, Sheila decided Victor needed a companion. Friends of theirs had offered them a French sheep dog and Sheila called and said, “I’ll take it!

Later in the day, the woman who’d owned Victor stopped by. “Would you mind if I took him for a day or two?” she asked. “I want to enter him in a dog show.”

“Be our guest,” said Sheila wearily, realizing too late that now she had on her hands one lonely French sheep dog.

But, as though determined to make good for his new master, Victor came home wagging all his ribbons behind him. “He took all the prizes,” laughs Sheila. “Furthermore, he won this long-handled maple ashtray that goes perfectly with the house.”

Victor’s ribbons are proudly displayed over the fireplace in their bedroom now, and Guy is enthusiastic about the pup’s future. “He’s just three-fourths grown, but I believe he’ll make a good hunter when I get time to try him out. Airedales aren’t too good at tracking, but they have a good nose, in the wind. They can smell pretty well in the wind a mile away.”

Take Sheila’s word for it—so can a wild goat. Now there was a moment. . . .

When the caterer, Mrs. Eric Blore, arrived to help prepare for the long-awaited Madison housewarming, she found Guy entrenched in the kitchen over a hot stove, trying out a new recipe for cooking wild goat. “Guy and Howard Hill had been experimenting for a year on the best way of preparing it,” laughs Sheila, “but on the day of the housewarming, Id been out shopping and I got home late. The caterer was there, we were expecting two hundred people, and Guy had a wild goat cooking in the oven!”

However, her husband, speaking as a wild-game gourmet, says wild goat doesn’t smell in any kind of a wind, when care is taken. “Goat meat isn’t strong at all, if you clean it right and prepare it properly. That is, if it’s a young animal, not over two years old.”

And for the benefit of those of you who may be collecting wild goat recipes, Guy continues: “You just put it on a grill in the bottom of a roaster, put in about one inch of water, add garlic and Tabasco sauce, cook it at 250° for four or four and a half hours, and you’ll have a pretty good piece of meat.”

As for the housewarming, baby Bridget was the star of that evening anyway—to the surprise of her mother, who watched Guy take various pals on a tour of the nursery. Before the evening had started, Guy had made a positive ruling on this subject: “We’ll keep the baby’s door locked,” he’d said. “We don’t want people running in and out of the nursery all the time.”

But during the festivities, the tinkle of glasses and the chatter of guests was broken intermittently by the clomping of Guy and some male cronies tiptoeing into the nursery. “I saw Guy sneaking off time and again at the party,” laughs Sheila, “with Rory Calhoun, David Butler, Andy Devine and different people. All of them sneaking so quietly—like elephants—into the nursery.”

Building their home was an exciting adventure. “It was a lot of work, too,” Guy says now of their picturesque redbrick and tawny wood ranch house high on its own hill in the Outpost section of Hollywood.

A lot of work. A lot of dreams. This house, which had been so close to Guy Madison’s heart for so long. His first house. While they were building it, Guy would drive by the house every morning on the way to the studio. And every night, the neighbors saw Wild Bill Hickok, a tired man in a buckskin suit, giving it a good-night look. Guy watched the house grow, board by board and brick by brick. All of them cemented together by hope and hard work—and by Guy’s unfailing faith through the years that a better day was bound to come.

Architecturally, the whole house was Guy’s idea—with one exception. One night, going over the blueprints with him, Sheila was stopped by a vast irregular area which took up a good part of the plans. “What’s this room?” she asked curiously. “My workroom,” he said. “What are you going to make, airplanes?” she asked, astonished and wide-eyed. Then, “Is this a bathroom?” she asked, pointing to a tiny area. No, Guy explained, that was the nurse’s room. “So I made a deal,” Sheila says now, “I got the workshop for the nurse’s room.

“You should have seen us putting the insides together,” she continues. “A tiny little piece of drape, a tiny square of carpet, a little piece of couch cover, and a sliver strip of Japanese grass-weave wallpaper. It’s impossible to see whether anything will go together that way. You have to have large pieces of everything. But it worked out all right,” Sheila sighs, her interested brown eyes appraising the deep green floor-to-ceiling drapes against the elegant silver-gray paper; the soft grayed wormwood paneling and the rich, dark oakwood furniture—every piece of paneling hand-picked, and every item of furniture custom-made.

The mail box outside reads “Robert O. Moseley,” with small print underneath identifying “G. Madison.” And the Moseley-Madisons are refreshingly identified with every detail of furnishing their new home.

Their smart bedroom-with-a-view is done in cocoa and blue with coral accents. “The cocoa drapes were Guy’s idea,” explains Sheila. “At first we painted the wardrobe cocoa, and it looked terrible. Then we painted it blue—that was my idea. And that’s Guy’s camera equipment all piled up on the end of the bar,” she laughs, keeping the credits straight. The handsome lamps in the living room, with the green shades and white organdy ruffles and the conversation-piece bases were Sheila’s love. One base is a sewing machine, the other a spinning wheel, “and they both work too,” she says.

Buying the crib for Bridget’s room stopped both of them. “That was a scream,” recalls Sheila. “We were both trying to look so wise, as though we were crib-shoppers from ’way back.”

They kept walking around the crib in the store, studying it as though deciding whether or not George Washington had slept in it. Finally, Guy turned to Sheila with, “What do you think?” And with an eye on the clerk, Sheila pitched it right back to him with, “Well, what do you think?”

“Guy was helpful with the bathinette,” Sheila says. “I didn’t know how to put it together—the stops and all—but he did. Do-it-yourself Guy.”

Bridget’s father is currently producing a combination toy box and window seat for the nursery. “It will be seven feet long and about seventeen inches tall when it’s finished,” Guy explains.

For Guy and Sheila, life centers around Bridget’s sunny yellow kingdom. They’re her constant subjects, along with a friendly white French poodle, a clown with a peaked cap, a flirty doll with red hair, a red-striped circus horse, and Bridget’s long-lashed “Lady” dog. All of them are under the command of a gay blade of a brown rabbit, a tall continental charmer, with a jaunty scarf around his neck—and quite a “past.”

“He was mine,” Sheila says of Mr. Rabbit. “A blind man made him for me in Paris. When I brought him over here, the Customs people looked so funny. I’m sure they thought I had him stuffed with diamonds or something.” And the way—eyes him, she may have the same idea.

Bridget’s first nurse was very strict about visitors, and as a result Bridget shies away from the exclamatory approach and sometimes draws back when people reach for her.

“It’s the surprise element, when somebody rushes upon her,” says Guy. “She has to get used to them.”

On the other hand, away from home, Bridget reacts with open arms. “But that’s different,” explains Guy. “If Bridget’s going out some place, she knows she’s going to be with people, and she’s prepared.”

“At eight months, Guy?”

“She knows!” her father says stoutly. And her mother seconds him.

The Guy Madisons go together like love and marriage. Dark-eyed Sheila, so gay and Irish and warm and tender, is a dream wife for a man with Guy’s seriousness, sensitivity and natural reserve. Her laughter is the happy music for a man whose emotions are so deep and whose scars are still tender.

“I have to keep calm outside,” Guy used to say. “When emotions run loose inside, you can’t think. And I have to think.” Until recently, he had little reason to relax emotionally. But nowadays, people are treated more often to the sparkle that flashes in Guy’s keen thick-lashed hazel eyes, and there is less of the set quality in the strong chin he’s needed to carry him through some very disheartening years.

“He tells me I’m a clown—but in a very nice way,” Sheila says. Watching television, however, is no laughing matter. Television and Guy’s addiction to boxing. “We have two TV sets now, but that doesn’t change a thing,” Sheila laughs. “When we just had one—and Guy wanted to watch the fights all of the time—I told him we were going to have to get another. About that time, somebody gave Guy one. It’s in our bedroom, and it’s never used. Guy says it’s no fun to watch the fights alone.”

Guy keeps a watchful eye on Sheila, too, through her pregnancy. “I feel better this time, anyway,” she says. “But if I don’t feel well—Guy’s so thoughtful and understanding.”

When Bridget was born, Guy theorized that the final hours were not so crucial—for fathers. “No worse than worrying, all the months before that time,” he’d mused. And typically, while he may not comment on his wife’s pretty new maternity outfit, he has a keen eye for any serious or significant eye-marks. Once, when they were playing golf, Guy made Sheila quit after they’d only played nine a “Your face is getting too red,” he said.

Guy has never been one to elaborate on what the little woman’s wearing, but he does generalize. “He says I look nice in anything—no matter what. ‘I’d like you in a sack,’ he tells me. And,” Sheila threatens, “one of these days I’m going to wear one and let him see.”

She missed a good opportunity to do this when she joined Guy on location in New Mexico, while he was doing “On the Threshold of Space.” Guy hadn’t filled Sheila in on the location problems, and she arrived there feeling like a debutante on a treasure hunt. “I thought they were shooting on the Air Force base. I gave Bijou a haircut, put red ribbons on his ears, donned my best pink gingham dress—and petticoated out to there. Then I went tripping out in the desert with my French poodle and all my petticoats— while they were all in jeans.”

“That didn’t bother her,” Guy grins, remembering how she’d cooked pinto beans and cornbread for seventeen members of the company—and won their money playing Liar’s Poker later on. “Sheila has a lot of get-up-and-go, and she fits in anywhere.”

Guy literally lights up at the mere mention of her name. Once, when a reporter asked him why he’d fallen in love with Sheila, Guy answered impatiently, “Well, you’ve seen her. You’ve met her—you should know.”

As Guy says, he “couldn’t be happier” facing fatherhood again. “I don’t care whether it’s a boy or a girl. It doesn’t matter to me—just as long as it’s a healthy and happy baby.”

If it’s a boy, he will be named Robert Ben, after Guy and his dad. “That’s what Sheila wants,” Guy says agreeably. “We’ll have to get a name to go with Bridget,” says Sheila. “I like Erin. Guy likes that, too.”

Guy’s disheartening years are being fast forgotten now. They belong to the past, not to today’s happiness, with his expanding fortunes and his expanding family. “I always have believed that, if you try hard enough—and long enough—you’re bound to progress,” Guy says philosophically.

And who can dispute that since, nowadays, the little living-room buckaroos who ride with Wild Bill Hickok are joined by the screaming bobby-soxers for the “new” heart-throb, and by their parents, for the mature actor Guy Madison is today. He also has his own independent company, Romson Productions, at Columbia Pictures, with “Reprisal,” the first to be made. “It’s the story of the conflict between the white man and the Indians from 1890 to 1900—the true story of the Indians at that time,” Guy says enthusiastically. “To my way of thinking, with the exception of ‘Broken Arrow,’ no good Indian pictures have been made. I think there’s a terrific field there.”

Out of gratitude and affection for the faith of his agent and discoverer, Helen Ainsworth, through the long years, Guy’s first thought was for her. “Now that I’m getting going, Helen, you can take it easier now. You won’t have to work so hard,” he said, and made her vice-president of his company.

He also signed a fat contract at 20th Century-Fox, “starting with two pictures, then a straight five-year deal with one picture a year.” But they’ve been keeping Guy so busy he has difficulty finding time to star for himself.

Heralded for his performance in a tough role in “On the Threshold of Space,” Guy’s now co-starring with Jean Simmons in 20th’s “Hilda Crane.” And upon being sought to star with Marilyn Monroe in “Bus Stop,” he reflected, “I’m not familiar with the part. I didn’t see the play. I haven’t read the script yet. I don’t know whether the character’s right for me.”

Nowadays, Guy is evaluating every role offered him very carefully. As he says, “Now the main thing for me to do is to watch the roles I play, to be sure the character’s right for me. I have to be sure I’m getting the right role—in the right story.” This time, he’s ready for Hollywood. “I’ve had fourteen years,” he says. “That should help.”

Guy was happy with his role in “On the Threshold of Space,” even though it was a grueling experience. In the part of a doctor experimenting for the Air Force in altitude checks, he wore three suits of clothing, worked with a big glass head-mask over his head and breathed through a tube. Working in intense heat he dehydrated. He lost thirteen pounds during the picture.

“It was a tough part physically and psychologically,” Guy says, “but I was happy to do it. I hadn’t played a part like this before. We had a fine director. They say it’s a terrific picture. I’m glad.”

Guy feels “Hilda Crane” will definitely further his career, and he couldn’t be happier, co-starring with Jean Simmons. “She’s so completely honest in the things I’ve seen her in, and I think she’s one of the top actresses in Hollywood anyway.”

It was an epic event for Guy to have a real leading lady, to be co-starring with a famous, glamorous actress in a sexy, romantic part. After fourteen years, this was quite a moment. Then, when Guy and Sheila met Jean for the first time, she sailed right past her handsome leading man—to his wife. “We’re going to be mothers!” Jean exclaimed.

Guy gives Sheila much of the credit for his successful career and their happy marriage. “The wife of a person in this business is about ninety percent of the husband’s success,” Guy says quietly. “And certainly this is true of Sheila.

“One of Sheila’s outstanding qualities is her ability to get along with ninety-nine percent of the people she meets, and be sincere about it. And I don’t mean being over-sincere. Sheila likes people, she’s intelligent, she converses easily, and it’s no strain for her to get along with them. This is very important, not only in this business but in any business.

“She’s familiar with the profession and its problems, which is an advantage in marriage. She’s considerate and under- standing. But most important of ll, Sheila has the right attitude. The attitude which naturally goes with marriage—any real marriage—two people working for one goal.”

In spite of all his amazing good fortune today, when a man like Guy Madison counts his blessings, he begins at home . . . with the happy fulfillment so long desired and so endearingly rewarding.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1956

No Comments