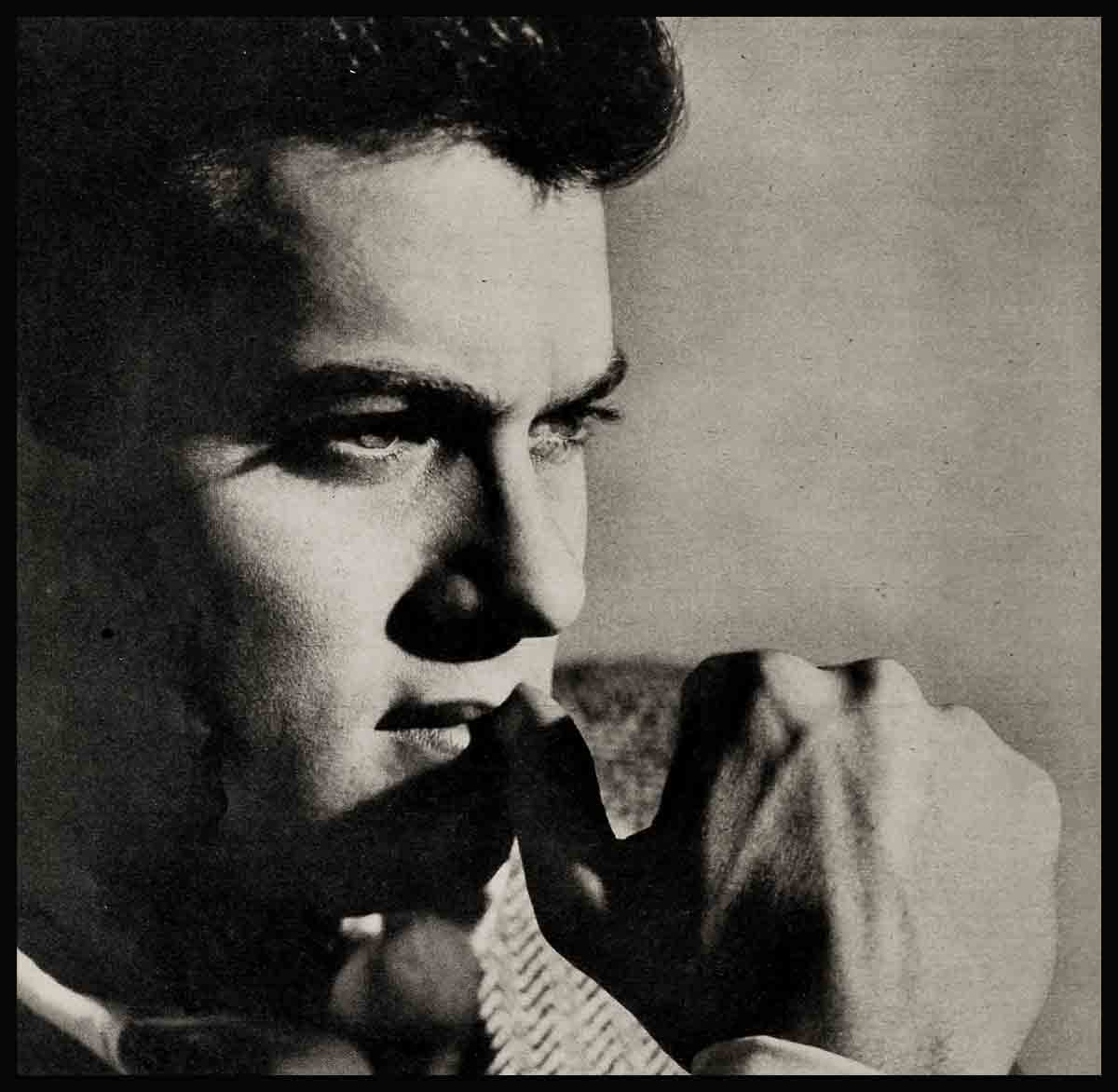

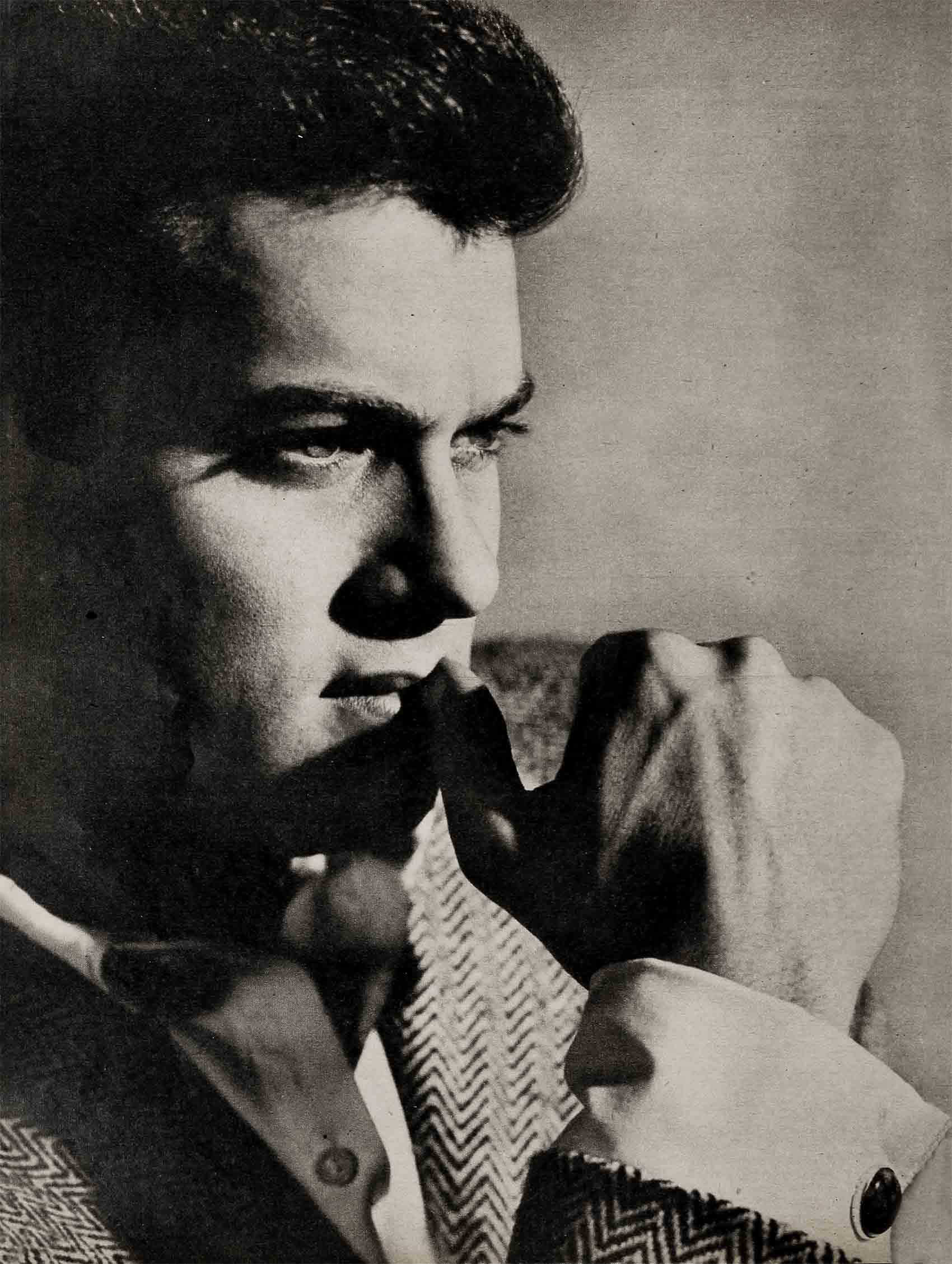

I Found God In The Streets—Tony Curtis

In the sections of New York where I was born and grew up I always had to count on competition. I learned even as a small boy that if I as much as stepped part way out of my shoes somebody would be sure to shove me all the way out so he could step into them. Seeing to it that nothing sudden happened to me took most of my time and I had little left to waste on worrying about the other guy.

Maybe I would have gone on like that if it weren’t for a strange thing that had no right to take place in a tough neighborhood—but did every ow and then. For no reason at all that I could see, and in cases where he couldn’t possibly benefit or be rewarded for it, a fellow would help his fellow man. Some dope! I would think, and try to forget about it. But sometimes it would stick in my mind and bother me.

Instead of thinking that the man who had received help was lucky, I found myself envying the fellow who had gone to all the trouble to help him. Somehow he had gained something. What? I used to puzzle over it and try to hammer my head back to where it would operate right. Gradually, over the years, I began to feel and understand the wonder of helping the other guy; why it was even better than getting helped, and that it was the human heart at work. In time I even knew that the heart meant the soul and that even here, in the tenement canyons of New York, God was around.

I got real smart at figuring out why people did certain things. (After I got to Hollywood I learned that the better the writer the more he knows about the same thing, that is, the motivation behind people’s deeds.) And I realized that there was not only unselfish action—there could be such a thing as unselfish thinking!

I remember one day in school when a pencil box was stolen and the teacher found it in my desk. She asked me why I had stolen it. I blazed up at her and denied the theft. I was so angry about her accusation, so fiery about it, and sounded so convincing that I almost convinced myself I was innocent. We stood there, face to face, and it was a horrible, ugly moment. Suddenly the teacher said something that just took the whole floor from under me.

“Oh, I’ve made a big mistake if you say you didn’t take it,” she cried. “I’m sorry. I apologize!”

What was this? She had me. She knew I was lying. I was willing to fight her off, but what kind of a dirty trick was she trying to pull by saying she believed me? And apologizing? I’ll never forget how shocked I was. And then suddenly I realized it wasn’t just a trick, that some kind of thinking and feeling—thinking I could only dimly be aware of as being in this world—was going on, that this teacher of mine had already figured out she didn’t want to prove me a thief; she wanted to show me that there was nobility in the world and here was a chance to give me a great, shining example of it.

I stood there swallowing, my anger gone. I wanted to cry. And knew that as long as I lived I could never be guilty of putting myself in such a spot again.

Redeemed: one dirty little thief. How? Someone wanted to help a fellow man up rather than kick him down.

What happened in that classroom didn’t die there. I had to ask myself questions about everything I was part of from then on, and the trouble with thinking is that once it starts it won’t quit. Mine led me to answers I didn’t want at first, and from these, painful as they were, to a new way of living.

I never considered myself a thief when I took that pencil box. No, sir. I, in the back of my mind, rationalized that being a poor boy, denied ordinary advantages, it was natural that I must help myself. (You notice that first I helped Myself to a fine excuse, after which it was easy to help myself to the pencil box.) The danger in that kind of thinking should be obvious. With the right kind of excuses nothing would be impossible for me—burglary, murder, what have you?

Or let’s apply it less spectacularly. Let’s see how it could work (and does work for a lot of us) in an everyday way. In my line of work if I don’t get the part I want in a certain picture I don’t have to waste any time analyzing my own possible inadequacies for the role. I didn’t get it because, clearly, the producer of the picture is stupid or a bum or prejudiced against me. So I complain to my friends and they comfort me. Or I tell my wife and she babies me.

After a while, if I keep on being this sort of fellow, I’ll get to depend on blaming someone. It will never be my fault.

This is what my teacher did when she helped me; she taught me me!

To help your fellow man you have to understand him. To understand him you have to understand yourself. I thought I had figured this out as a personal piece of philosophy when one day, while I was still a kid, I heard someone read something startling from the Bible. “Know thyself.” So somehow what I was learning by such slow degrees was connected with the faith of men.

Let me go back to the streets of New York and the boys I knew. The most characteristic thing about us was that we held the other fellow cheaply; his suffering, his problems, his reputation. This enabled us to cheat him, to play tricks on him, to forget him. Let’s take one of these tricks and look at it.

The automobile speed limit was about twenty miles an hour in our block, but most cars would shoot through at a rate closer to fifty miles an hour. And of course, we kids would be playing right out on the street—we had no other place.

When a car would pass we would pretend that it had hit us. We’d stand so close that it would brush our clothes, and at the last second we’d slam the rear fender with one hand and then fall flat. To the driver inside the slamming would sound exactly as if he had hit something, and when he looked back there would be one of us writhing on the street.

The scared looks on the faces of the drivers when they stopped their cars and came running back would tickle us. But what we were after was money. A lot of times they would pull out a bill and throw it at the kid, telling him he would be all right. And then they’d drive off again. What easy dough! And then one day the understanding of what we were really doing hit me right between the eyes.

We were holding human life—our own lives—as cheaply as they could be held. We were saying that a piece of silver could set to rights a broken body. Suppose I actually was hit by a car playing this trick? Of course I wouldn’t accept a dollar then. Yet that didn’t change the fact that a dollar was what I had established as the value of whatever might happen to me. The day I figured this out was the last time I ever bet my limbs, possibly my whole life, against a dollar or two! And I decided, too, that I was estimating people too much in terms of money and material possession; that I must start looking for other values.

What was a gentleman? At first the definition was easy for me. If I were a shoe-shine boy then the man whose shoes I shined was a gentleman. I was a shoe-shine boy around Seventy-second street and Second Avenue, but I learned that a lot of my customers were not necessarily gentlemen. Once my father, who was an actor-forced-to-turn-tailor, gave me one of his old whisk brooms to brush my customers’ clothes. “They’ll like that,” he told me. “Yeah!” I said, enthusiastically. “That’s a good idea.”

I tried it on my first customer. The whisk broom was old, as I said, and kind of frazzled looking. The man glanced at the whisk broom and knocked it out of my hand into the street.

“Keep that filthy thing off my clothes!” he said. Then he threw me a nickel for the shine and walked away.

I don’t know what made me do it but I ran after him. I wanted to remember his face. I was thinking of the kindness of my father in giving me the whisk broom, and how warm I had felt thinking how it would please my customers. And then it flashed into my mind that this was no gentleman; this was a monster of some kind because he didn’t know how to live with other people, and that it was this which made the difference between a brute and a gentleman. This and nothing else.

What was a lady? Surely she was one of those women you see sitting in the back of the limousines that sweep up and down Fifth Avenue. She couldn’t be the girl you know who lives across your own street, could she, or the one you call mother? It took me a while to be able to separate the quality of character from the appearance of respectability, to be able to recognize it out of a limousine as well as inside, against a background of poverty as well as riches. One day I met a girl I classed as just a pretty kid a fellow might neck around with. Before many days had passed I knew her as a lady for whom my admiration was boundless.

I was acting with a small theatre school then and she dropped in one evening to see our presentations and talk to her brother who was in our group. He introduced us and I took her out. She told me she worked at Gimbels, and did some modeling, too. As we talked on I became conscious of a fine mind working in her head and an appreciation of the world and its people that made my own knowledge seem pretty puny by comparison. This was not just a pretty kid—this was a person! It was wonderful being with her even if I didn’t get to hold her hand—which I did.

As soon as I could, I asked her brother about her, and what he told me confirmed my opinion. It was because of her help that he was able to attend an acting school; he had a $65-a-month G.I. grant but she made up the difference he needed to get along. She also contributed the major upkeep to the home so that two younger brothers could go to school.

I laughed. “You know,” I began, “when I first saw her I just thought she was beautiful. That’s all.”

He nodded and smiled back. “My sister is beautiful; inside as well as out.”

The memory of that girl stayed with me. When I met another one like her I knew it right away. This one was twenty-three years old, beautiful, too, well known, very busy at her own work, yet without telling anyone about it she was also busy just being a fine person. I don’t want.to go into too much detail because I don’t think she would like me to. But she’s still at it. It has to do with contributing to the maintenance and happiness of a large orphanage—and that side of this girl’s life was one of the reasons I thought it a great privilege to marry her.

You know, when you go to school you learn things in a clear order. But in life, especially in the dog-eat-dog kind of life I started out to live, you have to pick up things helter-skelter. I developed my faith, my philosophy of living, as you might if you picked up a Bible and read a page here and a page there, going backward as well as forward, and from the middle toward the beginning and end. And, as a matter of fact, what I learned from the whisperings of God in the noisy, dusty streets of New York, and for a long time thought to be my own exclusive wisdom, I later read in the Bible. The words were almost the same!

Let me say here that I am not a bit sorry I learned my faith on the streets first. That’s how it came to the men and the saints who wrote much of the Bible. That way it sticks with you.

It works out in funny ways for me. Take the Biblical injunction, “Do not bear false witness” I apply it to my work every day. I do not bear false witness for others and I do not ask them to do it for me. I am not talking about telling great lies, just everyday small ones. I never go to a friend and ask, “What did you think of my work in my last picture? Now tell me the truth: I want honest criticism.” I don’t do this because I know from experience that I don’t want him to be honest—I just want him to tell me I was great!

How did I learn this? Well, too many times I have been told I was great, too many times I found out later I wasn’t, and too many times I blamed the friend for fooling me. Now I know it wasn’t his fault. In such circumstances people instinctively know what the other fellow wants to hear and that’s what they tell him, feeling they would be cruel if they didn’t. So truth dies and a form of larceny takes its place.

In my earliest memories all life was defined sharply and simply, everything was black or white, sweet or bitter. From this I went on to the gradations. I began to see the greys and be more subtly appreciative.

From liking ice cream, which comes naturally, I went on to like music, which is more of a developed taste. From music I branched off to literature. At the same time I began to sense the beauty there can be in a snowflake, a leaf or a sunset. With these awakenings experienced, I no longer laughed when I read a poem or listened to it; now it meant something as the world was beginning to mean more to me. And not until then, I maintain, was I ready for the most subtle experience of all—the experience of being one with the whole meaning of existence, the experience of faith.

THE END

—BY TONY CURTIS

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954