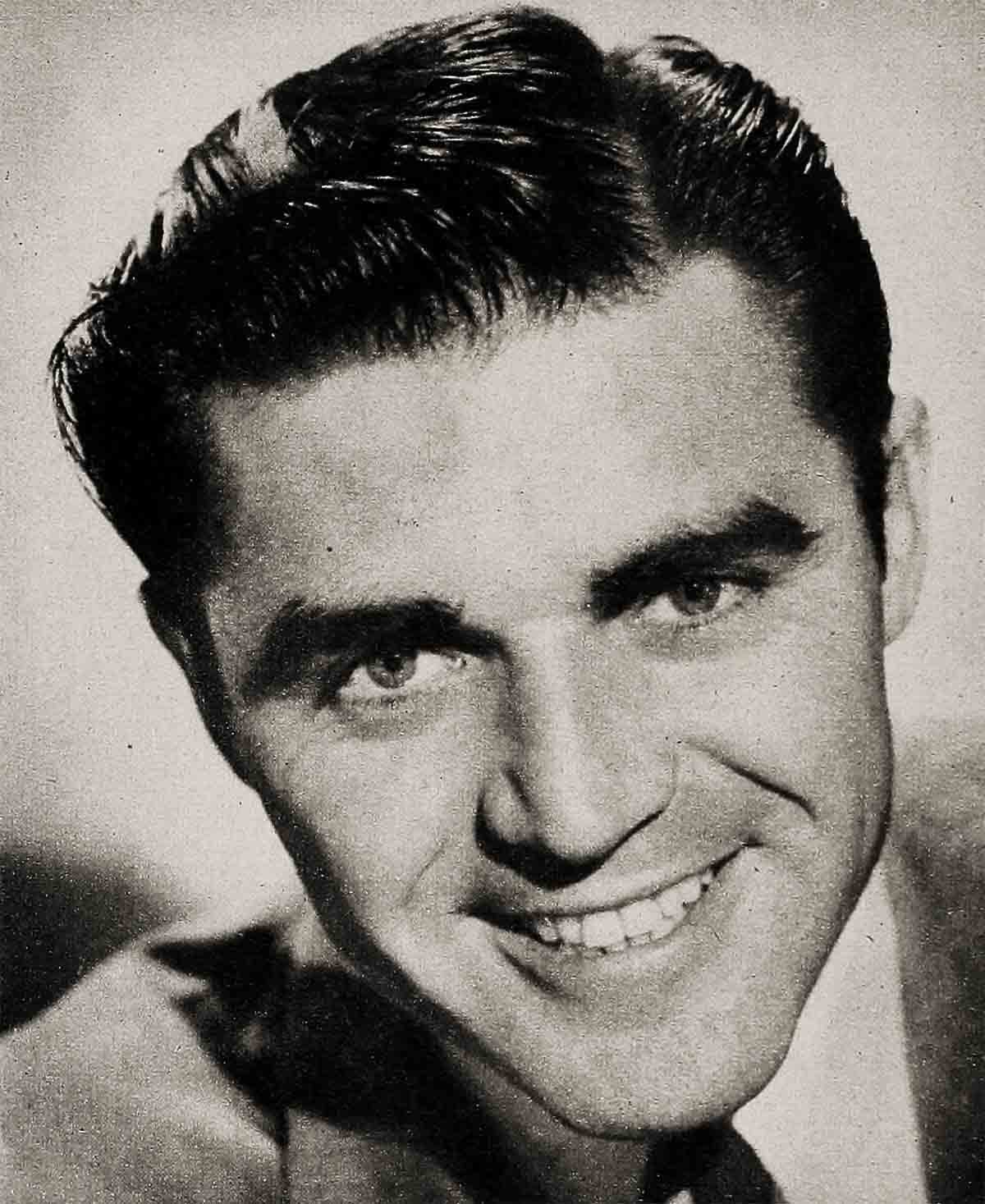

He’s Really Living!—Steve Cochran

Steve Cochran is a character. “But I’m not a Bohemian,” he announces. “A Bohemian uses bacon for bookmarks.” Despite his denial, it’s probable that Steve Cochran would use bacon for a bookmark, if he couldn’t find a bookmark. He would also do a lot of other things that ordinary, nose-to-the-grindstone actors would not ever do. Who else in Hollywood would keep a parrot named Clarence, and a dog named Tchaikowsky who plays the piano? Who else would admit with a devilish grin that women are his favorite hobby but that marriage makes him miserable?

Here is a man who even gets Hollywood excited, because he is like no man Hollywood ever saw before. He is lazy, but always interested; he is casual but suggests controlled power; he plays at love, but his heart is with the sea; he lives in a house that looks as if it were built by a madman.

The house climbs a hill in Benedict Canyon, and the living room clutches the top of it. Walk through the door and you come face to face with a bar, and if you keep your head up you’re liable to be conked on it by a four-by-four beam that is slung low across the ceiling. Everywhere there are potted plants crying out for water. Usually there’s a party going on. People drift in at all hours, rifle the ice-box and carry their loot back into the living room where they sit on the floor and eat before the fireplace. Sometimes, if a lady’s around who knows how to cook, she cooks. Or else Steve will whip up a dish that originated in Lithuania or Tibet. He likes to give parties because when they’re over he’s the only one who doesn’t have to worry about making the trip home.

Steve Cochran is not an easy man to know. He talks very little about his childhood, although his family seems to have shared his easy-going attitude toward life. He was born nine years after his sister Vina in Eureka, just off the coast of northern California, where his father worked in a lumber mill. From the schoolroom in Eureka, Steve could hear the pounding of the surf on the beach, and more often than not he played hookey to sit on a jetty looking out over the Pacific and dream of sea-faring.

Before he finished third grade he’d been in love seven or eight times, but this career was interrupted when, at eight, his family decided to take him to Denver, Colorado, on a visit to his uncle. They got as far as Laramie, Wyoming, where the family jalopy, and the family finances were both exhausted. They were not only flat broke, but stranded in Laramie’s worst snowstorm in years. For seven days and nights nothing moved in or out of the city, and Steve’s father got a job in an ice house. They figured Laramie was a likely city so they settled down there and put Steve into school, where he fell in love the first day.

Steve can’t figure now how his parents got the money—there never seemed to be any left over—but somehow they enrolled Vina in college. Despite Vina’s having one of history’s most tormenting kid brothers she got through, taught school one year and married. This left Steve more or less on his own where family life was concerned. His mother worked off and on, he never seemed to be close with his father, and almost their last act as a family unit was their trip to Denver, which they finally made.

From the time he was 12 to 15, Steve’s summers were spent working on surrounding ranches, and on high school vacations he earned money as a gandy dancer. A gandy dancer, explains Steve, is a shoveler on a railroad section.

His name was enrolled and stayed for one year on the student roster at the University of Wyoming. He left because he couldn’t see any sense in studying dramatics if he wanted to be an actor. He figured the only way to learn was to act.

Steve tackled it the rough way. His first acting job was with a Federal Theater project in Detroit, a city which he remembers with considerable displeasure because of his various lodgings there. No matter which boarding house he tried, the results were always the same. He had to creep quietly into the beds, for if he jumped in with any force he was choked by the resultant mist of green powder (bug-killer) that enveloped the room. This green powder has become synonymous in his mind with Detroit, for it was always there, in the corners, on the floor and in the mattresses. The sad part was the bugs seemed immune to it.

Steve tried Hollywood a few times, leaving it as soon as he had train fare. For Hollywood in the late 30’s wanted men with lean jaws and drawing room noses. In those days, Steve Cochran looked like an itinerant who specialized in cow punching and gandy dancing. He soon added to his list of vocations, becoming a carpenter, a policeman, and a shipyard worker.

All this was neatly interspersed with acting jobs here and there. Once he directed and acted in the Junior League’s Theater For Children in San Francisco. “As an audience, those kids were monsters,” he says grimly. “Unless some guy was being stabbed or shot on the stage, they weren’t interested. All they did was run up and down the aisles, puncturing each other with blow guns.”

He kept trying Hollywood, and Hollywood kept sneering. His first real start was when he played opposite Constance Bennett in the Theater Guild road show of Without Love. On opening night in Columbus, the always confident Cochran suffered his first case of stage fright. “You’re stupid,” he kept telling himself. “You’re opening in Columbus. Who’s covering the show in Columbus? Calm down.” But he didn’t calm down and when he opened his mouth to speak his first lines, nothing came out but a humiliating squeak. He carried on in true fashion after that, and never again had any trouble unless it was’ the shattering experience in John Loves Mary. As the hero, Steve was to remove his trousers in the second act, and soon after the curtain had gone up on said act, a terrible realization came over him. In the next clinch with the heroine he whispered desperately into her ear, “I haven’t got my shorts on!” After her next exit from the stage he could hear her footsteps tearing across the boards behind the backdrop, and when she came on again she gave him a reassuring nod. At his next opportunity to fade slightly out of sight he slipped into the wings, ripped off his trousers, and literally jumped into the shorts that were held there waiting for him.

Had he not done some quick thinking he would have found himself in a situation embarrassing even to him. For Steve may be a character, but he does draw the line. He bemoans, for instance, the fact that he has a reputation for being a 16-cylindered wolf. A lot of men, single and attractive, would find such a reputation to their liking, but Steve shudders for the times he has asked girls for a date and they’ve backed away from him, all but screaming with fright.

“Ye Gods,” he says helplessly. “I’m only a man.” But that, the dolls figure, is precisely the trouble.

He claims he’s quite serious when he’s in love but admits that his heartache over a broken love affair lasts from two P.M. to four P.M., at which time he once more has his eyes in focus. He was engaged four times, and married twice, once to Florence Lockwood, daughter of a portrait artist, by whom he had his only child, a daughter Xandria, and once to Fay MacKenzie. His first marriage lasted eight years, the second two years. Steve has now been single for three years and likes the idea.

“Once in a while,” he says, “I start thinking about the advantages of marriage—a home and an anchor and hot meals and all that—and then I catch myself up. Whoa, boy! You’d be miserable within a year.”

Steve likes his freedom. Considering the fact that most of his friends are married, he was once asked if he didn’t feel like an odd wheel with them. “Nope,” he said. “They’re the odd wheels.”

For companionship he has Tchaikowsky, and few men could ask for more. Tchaikowsky is a mutt, which fact cannot be safely stated in Tchaikowsky’s presence. Tchaikowsky has to date bitten 21 people and been quarantined 19 times. The two times he escaped quarantine were pure luck and only served to make him wonder what was wrong, because he has come to expect such action directly after the spanking given him by his master. Tchaikowsky is part Schnauser and part heaven-knows-what, and was so-named because he has a faint resemblance to the composer, except, of course, that he is very much alive. He also has a slightly frightening countenance, as witnessed by the fact that one visitor to Steve’s home keeled over in a dead faint when first beholding the dog. The man was sitting in the living room one night, facing the window behind Steve’s back, and suddenly his eyes went past Steve to the window and his face froze in terror. Tchaikowsky was out there, standing on the hill by the window, which made him appear to have the height of a man. The light from the living room shone out and revealed two glaring eyes and a pair of appalling fangs, framed by a stiff mass of hair which stood straight out from the face. Nothing else was visible but it was enough, and the visitor breathed a choking sigh and lost consciousness.

Tchaikowsky was acquired 11 years ago by Steve as a decoy in the matter of meeting a girl. This particular girl had a supercilious Afghan which she used to walk in Central Park every evening. It was spring, and Steve had a hankering to meet this girl. He tried every ruse in the books but received only fishy stares for his pains, so as a last resort Steve became the owner of Tchaikowsky. Armed with his mutt, he sallied forth on an evening in May, certain that dog owners could always start a conversation. The end result of it was that Tchaikowsky bit the Afghan and the friendship never got started.

Tchaikowsky is, in his inimitable way, almost as famous as Steve because Steve talks about him all the time. Once Steve watched the dog coming home along a Carmel road, watched him pass a little boy without so much as a flick of his dog eyelashes. Thirty yards past the boy, Tchaikowsky turned on a dime, bolted back and nipped the kid in the derriere. “I don’t know what gets into him,” Steve says. Another time, when Steve was up in Folsom making Inside The Walls Of Folsom Prison, Tchaikowsky up and bit one of the guards. But the dog’s real fame has come from his ability to play the piano. This he will do-most willingly, in a haphazard way, at a whispered command from Steve, and once, when Steve got the idea of having Tchaikowsky play on a personal appearance tour with him, the dog made headlines when he tangled with the Musicians’ Union. The dog could not play the piano, said the union, unless there was a standby musician, or a full standby orchestra in the pit, or unless he got a membership card. Tchaikowsky was furious and would have bitten Petrillo himself had the man been available.

The dog accompanies Steve wherever he goes, with the possible exception of Hollywood cocktail parties, but Steve shies away from these. “Ugh,” he says at the mere mention of one. “Everybody trying to impress everybody else.” Tchaikowsky did used to play the piano in sundry saloons. In appreciation of his talents the customers would toss pennies, and inasmuch as Tchaikowsky had no use for coins of the realm, Steve would collect a beer or two for himself.

Steve’s dream idea of entertaining consists of aRoman style dining room. He wants a long, long table down the middle of the room, surrounded on all sides by comfortable couches. To lie down while eating is his idea of Eden, and he probably wouldn’t object to having grapes dropped into his mouth by a batch of curvesome cuties.

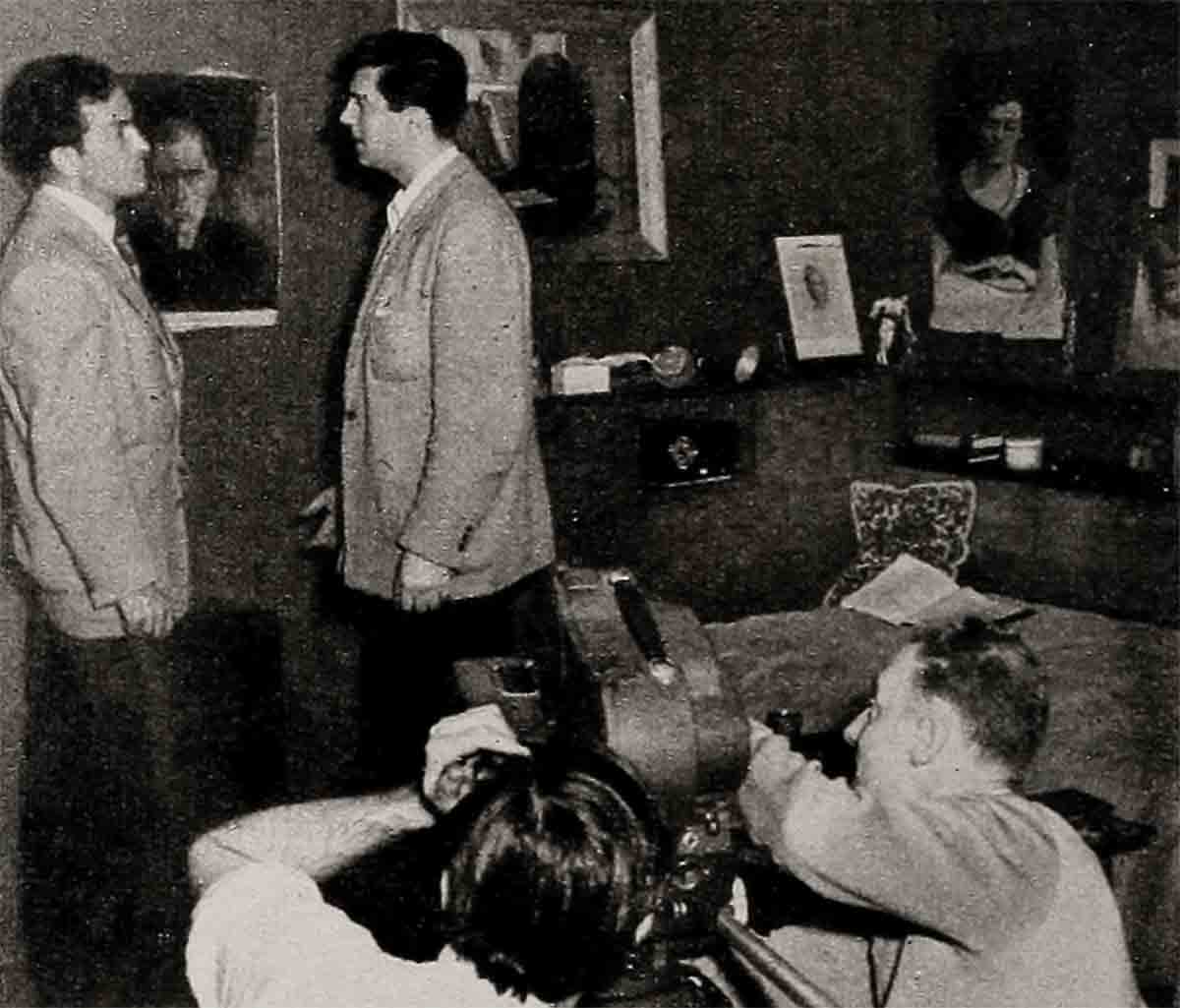

The impression that Steve never moves unless necessary is erroneous. He just seems that way. He owns a 24-foot ketch which he keeps harbored at San Pedro, and is a Sunday afternoon sailor. If he doesn’t sail, he paints or caulks. scrapes or polishes, and although he’s never had the boat out longer than two days, he’d sail more if he didn’t have other things to do. He rides a lot, and is making a home movie with some pals who have managed to get together a script, camera, sound equipment and lights. The film has been shot spasmodically for some months now, in places like the San Pedro wharves and a San Francisco boiler room. He writes letters to his mother, who now lives in Alaska, the result of a round trip ticket some six years ago. Mrs. Cochran decided she liked Juneau, in much the same manner she had liked Laramie, cancelled her return ticket and now runs a restaurant there, on the wharf.

Steve writes letters to his daughter in Carmel and fiddles about with the writing of plays. He keeps promising himself, every week, that he will start painting again, but there never seems to be time enough and his brushes and canvases remain in the closet. He studied art at one time but could never make up his mind whether he wanted to know about fine art, illustrating or cartooning, and settled on acting instead. His friends from Laramie keep in touch with him, one pal in particular who engineers trains through Wyoming, and wants to know why on earth he doesn’t “come home for some hunting or fishing.” Steve is paradoxical in that despite his boyhood in the wide open spaces he doesn’t really miss them at all and enjoys himself in the city just as well.

“If I ever had my swan song in Hollywood,” he says, “I’d go back up to Maine and work in a shipyard. You can always do something, you know. Or maybe I’d join the Merchant Marine. Every time I work on a boat for a picture I get the urge ba sneak off to sea and leave the picture flat.”

Travel has a strong fascination for him, not because he wants to visit famous libraries or castles or shrines, but simply because there are places he hasn’t seen. He associates cities he has visited with strange memories. As it was bug powder in Detroit, it is whistling kids in Philadelphia. “Never saw anything like it anywhere,” he says. “You drive down Broad Street and on one corner a bunch of guys are standing there and they all whistle when you go by. The next corner it’s girls, and they whistle!”

When he’s at home in Benedict Canyon, however, he contents himself easily. He has a battered collection of records which includes chamber music, and a library whose most well thumbed books are those by Shakespeare, Jack London and Erskine Caldwell. And he has his friends and he has Clarence and Tchaikowsky.

Steve takes life as it comes and doesn’t argue with it. He is completely without pretension. He is a charming bachelor not constituted for marriage, but there’s hardly a female fan who wouldn’t be happy to get one good crack at becoming Mrs. S. Cochran.

THE END

—BY IMOGENE COLLINS

(Steve’s latest picture is Warner Brothers’ The Lion And The Horse.—Ed.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1952