How A Star Is Born

A player is given star billing by a studio when that player can “carry a picture.” This phrase means simply that the name appeal of the player has become great enough to attract audiences to the box office in sufficient numbers to return a satisfactory profit to the studio. A star must be able to “sell tickets.”

Top stars in Hollywood may be divided (very roughly) into two groups: the young arrived who are the prime favorites of audiences between the ages of twelve and thirty, and the secure players who are favorites of audiences of any age; such players as Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Irene Dunne, Barbara Stanwyck, Olivia de Havilland, Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy, Cary Grant, Fred Astaire, Bing Crosby or Bob Hope.

To the uninitiated, the bestowing of stardom may seem as spectacular an event as commencement. Unfortunately, stardom is almost never accompanied by fanfare. Usually it happens in this way: One day a young player appears at the studio, after having made a series of pictures that had given him a chance to show to increasing advantage how well equipped he was. The player is told by a studio official, “The front office has decided to star you in your next picture. They’re looking for a script which will be just right.”

This would be great news if it weren’t for the fact that—by the time the announcement is made—the player is well seasoned in Hollywood lore. He knows that months, possibly even a year, may go by, before the perfect script may be found.

John Derek’s experience is almost typical: After his brilliant work in “Knock on Any Door” which rewarded him with stardom, he was idle for eighteen months before he was cast in his first starring vehicle, “Rogues of Sherwood Forest.” True, he was drawing his modest salary during that time, but inactivity preys on a player’s mind. An actor must act if he is to remain an actor.

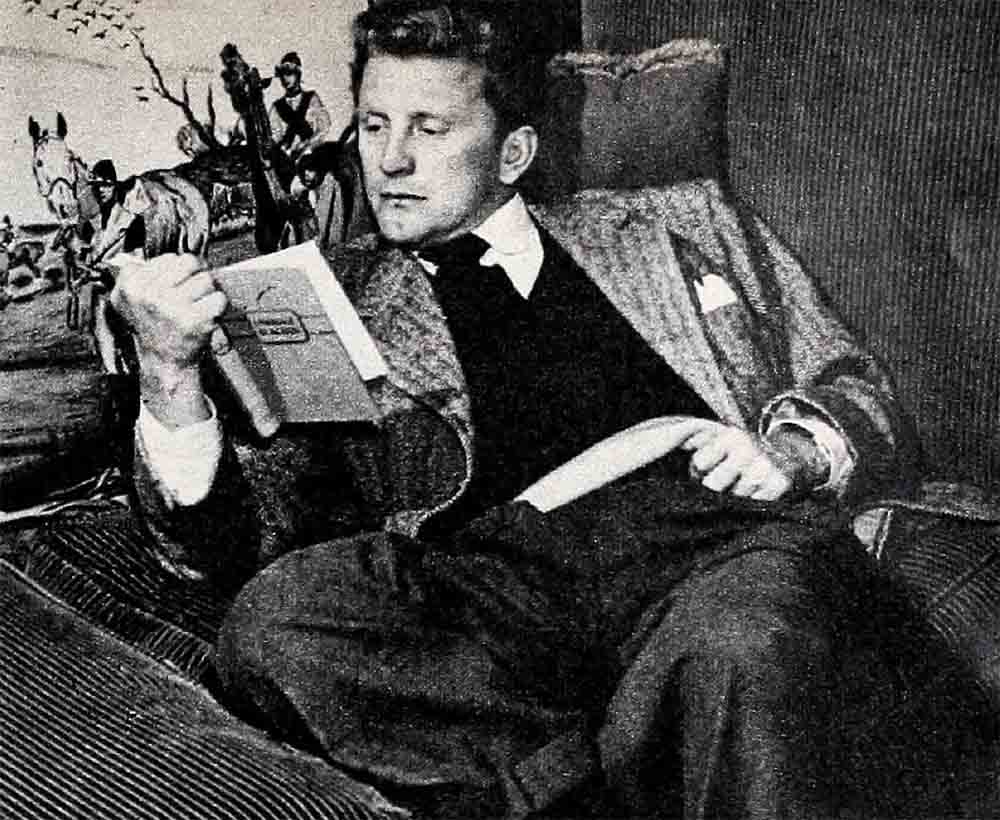

Like many another well-prepared and talented newcomer, John had a background of character-building experience to call upon while he waited for his first starring picture. He had been under contract to David O. Selznick for a year, and had had only minor roles in two pictures: “Since You Went Away” and “I’ll Be Seeing You,” under the name of Dare Harris. He had been under contract at Twentieth Century-Fox, and had not made a picture. Now he was under contract to Columbia, and if a man could live with fingers and toes crossed, he would have done it. He was also practical: He spent a full business day, every week day, at the studio. He spent several hours daily studying with famed drama coach Benno Schneider. He haunted sets; he saw a picture almost every night. He was in training quite as much as if he had been trying to make a football team, and he didn’t relax his efforts or give in to discouragement for eighteen long months.

Kirk Douglas scored in “The Strange Love of Martha Ivers,” but made very little headway for nearly two years, until “The Champion” was placed in production.

The list of similar experiences is endless.

However, once that first starring picture has been completed, a new set of problems arises. There are suddenly twenty scripts crying for the casting of this star. The bewildered star is delighted to have five pictures lined up in advance. He reports on the set thirty minutes early each day. He has a week off between his second and third picture, a weekend off between his third and fourth, an afternoon off between his fourth and fifth.

One morning when he awakens he finds himself done in, totally exhausted, shot. He calls his studio and explains. Usually his breakdown has been anticipated, so the majority of his coworkers understand, but someone, for some reason, is certain to report to a columnist that the player has developed “temperament.”

At first, the fact of his “temperament” being considered copy for a syndicated column strikes the player as being faintly absurd. He is likely to dial the scribe’s number and set things right. However, after thought, there comes a towering realization: He, the struggling nobody, has become a star; henceforth, everything about him is news.

If you were such a star, you would read rather intimate disclosures of your plans or your problems in magazines and in gossip columns. A Hollywood picture star soon finds that everything said or thought about him finds its way into print.

Having absorbed this truth, you—as an arrived star—must steer a careful course. You must not be dull, for to be dull is the capital crime in theatrical circles, but you must not be notorious, either. Nowadays, studios are not inclined to overlook the antics of theatrical problem children; there are too many talented people who are available and begging for jobs for studio officials to endure stars who bring calumny upon Hollywood.

No matter how hard a star has worked to attain stardom, there is still more work, more study, more grooming, more seasoning to be done.

When Anne Baxter was cast in “You’re My Everything,” in which she was required to be a flapper (1923 era), she spent weeks in the hairdressing department experimenting with a coiffeur which would please both herself and the director.

During the years of her apprenticeship and her stardom, Anne has changed her eyebrows “at least twenty times.” Currently she is back to her natural contours.

Like almost every other young player in Hollywood, Anne sees as many plays as possible, and when Los Angeles’ few legitimate theaters are dark, and a trip to New York isn’t possible, Anne, John, and a group of their friends get together and read new plays aloud.

The arrived star tries to do as many radio programs as possible because radio is a polishing medium. Incidentally, the background people or bit players in radio are highly esteemed by picture players.

Everyone who knows anything about the theater is familiar with the cliche that a successful comedian yearns to play Hamlet, and a successful tragedian aspires to enact the court jester.

Donald O’Connor, a thoroughly competent young comic, has something to say on the subject. “I’m perfectly honest about it: I’d like to play Hamlet, or Romeo in ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ or some such heavy drama. Why? Well, once a player has attained success in a certain type of role, there is a tendency on the part of producers to cast him repeatedly in the same sort of thing. Young stars are right when they protest against repeating the same characterization endlessly. To preserve themselves as many-sided performers, they must fight for a change of pace.”

Another professional responsibility of the successful player is to look like a movie star when away from the studio.

Being glamorous on the set is fairly easy because of the studio’s staff of technical talent whose job is keeping a star’s appearance tiptop.

Away from the studio, when a star is shopping, driving about the city, going to the beach, or merely relaxing, it is natural to do as the rest of the world does in similar circumstances—and relax about appearance.

The arrived star soon discovers that ease is for the inconspicuous. A famous person who is seen in old dungarees, world-weary sweater, sweatshirt or antique mocassins, is criticized.

Until you really make a study of the problems of assembling a wardrobe, you may think—as the average woman does—that if you spend large sums on your clothes you will automatically be a candidate for a “best-dressed” list. This is a mistaken idea. One famous Hollywood personality who spends staggering sums on clothing, has a reputation for being wrongly dressed. She always wears too much at everything: Jeweled pins, necklaces, feathers, flowers, veils and hats.

Once you have mastered the wardrobe problem so that you never have to step into the closet and say, “I have nothing to wear,” you, as a newly arrived luminary, are faced by a far more subtle social problem:

One great sadness has tempered your success—many of your old-time friend have slipped away. Some have succeeded along with you (and these have become more important than ever to you), but the majority have lost the race.

You have tried to keep in touch with those whose luck has been bad, but life moves faster than the human will. You haven’t had time to place the leisurely telephone calls. It is true that you haven’t changed in some respects, but in others you have, and there is no help for it.

The fact remains that in whatever efforts you have made to keep the old friendships, something has gone wrong. You have tried too hard, and the friends have held back. So you, like every other arrived star, would find your circle of friends changing. You would be invited to some truly charming social affairs.

At such parties you would be likely to meet literary celebrities such as James Hilton, James M. Cain, Frank Scully, whose new book about flying saucers is being talked about, and Anita Loos, of “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” fame. You would find that you would be more comfortable in such company if you knew and could discuss something of the work of authors like Dickens and Dostoevski, Flaubert and Faulkner, Henry James and James Michener. If you were lost when the conversation skipped away from the comics, you would decide to find out exactly with what Dr. Eliot’s five-foot-book- shelf was stocked and to read every book.

Your further education would not stop at literature. You would begin to haunt art galleries in your spare time. On personal appearance tours, you would do your best to see as many galleries as possible, and you would buy and study books about the art of sculpture. You would understand why Cary Grant enjoys the work of Raoul Dufy and why Eve Arden buys Grandma Moses.

You would have a record collection ranging from Bach to Berlin. You would buy for reference such useful works as “Great Symphonies; How to Recognize and Remember Them,” “Great Program Music; How to Recognize and Remember It,” both by Sigmund Spaeth, and “The Music Lovers’ Handbook” edited by Elie Siegmeister.

In brief, you would be broadening your horizons and further acquainting yourself with the magic world of the creative artist.

So much for the upward and onward phase of your life at this particular stage of development.

Unfortunately, your personal problems would have increased along with your fame. One of the greatest would have to do with money.

Your pay checks would be, in your own eyes which are in a measure still those of a struggling dramatic student, colossal. You would have to kick yourself to remember that the money was not yours. Federal and state income taxes would take seventy per cent and over of every dollar you earned. You would awake some morning to discover you were in deep financial difficulty. You would have bought a new car, a new home, a new wardrobe and suddenly would have realized that you didn’t have enough money in the bank to pay your income taxes.

You would employ a business manager who would put you on a budget. You would find yourself in much the situation of Donald O’Connor, who has avoided trouble because his business manager allows Mr. O’Connor exactly fifty dollars per week for expenses. The rest of his check pays his bills, provides for taxes depreciation, and savings.

In addition to your own financial problems, you would discover what almost every other celebrity has learned: Every family loves a successful member. You would be informed that Uncle Threadbare always knew you were a good boy and could succeed, and would you please make the next payment on his mortgage. You would be told that Cousin Sulphur was coming to Hollywood and would like to live with you until he could find work and living quarters.

It also is at this particular stage of a star’s development that a new and sometimes terrible element enters his or her experience, and it is especially terrifying to realize that the element is likely to become an integrated part of life from that point on. It is called Loneliness.

Many a beautiful girl sits at home because she has no escort for an important social event. This is her problem. If her first marriage has broken up, she is beset by wolves until they learn that she has integrity, then they disappear. The nice boys the ones she would welcome as friends, are afraid to seek her, first because of her eminence, secondly, because many of them can’t pick up the check without living on beans for the rest of the week and third because they are afraid of being turned down if they should ask for a date.

Even when a girl is happily married, she cannot escape long periods of loneliness particularly if she is married to a man who is also in the picture business. Two careers in the same household are tricky to manage. There are times when a man must be away from home. A wife who has no career can follow along, but when she’s an actress under contract, she has to remain on the job. Also, when she is sent on location I her husband can seldom accompany her.

A girl who remains in Hollywood while her husband is away, is restricted in her activities. Her agent might like to take her dancing. And certainly there could be no criticism leveled at such an outing if the situation were understood. Nine times out of ten, however, the agent’s face is not as well known as his name, so he and the star are photographed, and the photograph is widely circulated with the caption, “Beautiful Helen Hennessey dancing at Ciro’s with a friend.” Whereupon the next voice you hear is that of rumor suggesting that Helen and husband are rifting.

The established star has another great enemy in addition to loneliness: it is time. Everything seems to take more time than it should, and there are more and more activities crying for their share of time which does not exist.

Have you ever thought that it would boost attendance at your charity benefit if Jeanne Crain only would attend? Has it occurred to you, when Kathryn Grayson was in your town on a personal appearance tour that it would aid your church festival income if Kathryn would autograph records in one of your booths?

Such ideas occur to thousands of people all over the world whenever a celebrity is in the vicinity, or is within flying disance of a town.

When the star is in Hollywood, he or she is living in an area populated by some four million people, all active, all eager for celebrity help in putting over a pet project.

All of these are the outside problems of the young star. They have to do with the exterior which faces the world. Far more serious problems are those of the spirit. Shortly after the player has attained the pinnacle which he has been climbing with fine disregard for his anguish and arnica-covered ambition, he is likely to develop a crushing anxiety complex.

Let us say that you have arrived; your name is known throughout the land, and your picture appears monthly in every notion picture magazine.

But striving has become part of your nature. You have to be fighting for something. You try to do too much. You make too many personal appearances, you show up at too many benefits, you manage to be too social, too professional, too frantic.

You look around at the newcomers. They are, usually, younger than you, fierier, keener, not so blunted by experience and hard-won knowledge. They seem to be better equipped, and the chances are that their training has been better because each decade provides some human progress.

If you aren’t careful, you will end on the ’ouch of a psychiatrist.

However, it should be pointed out that awareness of competition is not entirely a bad thing. No established player, glancing over his shoulder at the gifted, sparkling new crop coming on, dares to let down. He stays younger, he looks better, he keeps alert and vital longer, he gives himself a better life, and gives everyone he meets a better person to know. He cannot afford to grow fat, physically or mentally.

There are many other satisfying facets of theatrical success, but at least two should be mentioned at this point.

If you were Betty Hutton, you would have met General Eisenhower and have come to know him while you were entertaining troops overseas during World War II. If you were Hugh Marlowe, you would have met Einstein. You would get to know, because you were well known, the leaders in government, in business, and in the arts.

If you managed your money carefully, you would be able to give material comforts to your loved ones. When Donald O’Connor was honorably discharged from the Army he discovered that he had reached the age of twenty-one and could use the funds accumulated during his saving years as a minor.

He bought his mother a house. He bought a house for his brother. He bought a car for each. He bought Gwen a fur coat. Donald’s experience is typical. Show business people are notably generous with those they love. They do what all loving people throughout the world would like to do.

Success of every kind is a dream come true, and you—like the usual Hollywood star—would be gay, kind, generous; humble, grateful and dedicated if you had arrived at your cherished goal and all of life spread before you, a roseate panorama.

No matter how high a successful star may go, there’s always another height to be scaled, other problems to be solved. Next month’s instalment tells you how some of the stars solve the problems that face them.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1951