The Heart Is Everything—Doris Day

She’d just turned fifteen and life was over. She was lucky, they told her—she and the others who’d cheated death. This was true, yet the truth failed to sustain her. Last week she’d been dancing, now she lay like a strange block of cement in plaster casts. How could a gay, harmless evening lead to such blackness? How could the years of her life add up to this? Some day, when she was an ancient eighteen, she might walk again, on crutches or with a limp—if she stayed lucky. Against wave after sickening wave of disbelief, her face turned toward the wall, but monstrous contraptions held her body fast. From under the closed lids, hopeless tears welled and soaked slowly into the pillow.

The girl in the bed was Doris Kappelhoff, whose legs had danced from babyhood to the rhythm in her blood. The rhythm she owed to her father. A teacher of German in the Cincinnati schools, his spirit fed on music—but real music, as he called it. Anything less dignified than Brahams offended his soul. The popular records Doris loved were trash to him, and he had no patience with them. Nor much more with the vagaries of childhood. Brought up in the strict Teutonic school, he followed the same pattern with Paul and Doke. (To him she was always Doke, maybe in simple affection, maybe in protest against the foolishness of naming her after Doris Kenyon, her mother’s favorite movie star.) Just as popular music spelled trash and no arguments, nightmares spelled nonsense. When she woke screaming against phantoms of terror in the dark, her screams would be choked by the voice of paternal authority. “Go right back to sleep and stop imagining things.” Rigid amid the clamor of her pounding heart, she’d wait for her mother’s footsteps, her mother’s figure in the doorway, the blessed comfort of her mother’s arms, shutting out all danger.

Why the Kappelhoffs separated is their own business, which is how they kept it. That they were temperamentally unsuited seems fairly clear. That tensions must have mounted to an intolerable pitch seems equally clear, since in their circle, man and wife stuck together, if sticking were possible. They parted in ’35, when Doris was eleven. Whatever the cause, any rupture in a child’s background affects the child. Alma Kappelhoff eased the break by fostering friendly relations between her estranged husband and his children. Growing older, Doris grew in understanding of her father and wrote to him regularly. But she remained the child of her sunny, outgoing mother.

Unwilling to disrupt their lives more than absolutely necessary, Mom kept the big nine-room flat that had always been home, and went to work. If they were shorter on cash, they were longer on freedom. Nobody now to keep Doris from spinning her platters, and whirling like a young dervish all over the house. Once, as she broke into song, Paul pricked up his ears. “Hey! Maybe you should make with the pipes instead of the feet.” Cherishing this rare tribute from an older brother, she paid it no further mind. Dancing was what came naturally, and her feet might be her fortune. That’s what they said at Hessler’s Dancing School. That’s what they said at school and church affairs, where she teamed, up with Jerry Doherty. With Jerry she entered the contest staged by a local department store and they waltzed off with first prize—five hundred bucks. This windfall, their mothers decided, must be used for the children. What better use than to further their careers, what better place than Hollywood? Westward they traveled and reaped a small triumph. Impressed by the kids’ comedy routines, Fanchon & Marco booked them for a series of summer shows. In high fettle, they returned to Cincinnati and school, practically professionals. A little more wrestling with stuff like algebra, a little more growing up and they’d be on their way.

A former classmate who’d moved to the nearby town of Hamilton asked Doris over. A boy friend was coming with another boy to take them for a drive. The boys were cute, the moon was full, the evening lovely—until they reached the unguarded tracks, and from out of the peaceful night saw doom descending in the headlights of a fast freight. For a split second, for an eternity, they sat in frozen horror. Then it hit—ripped the hood away, dragged them a block and a half, came at length to a shuddering halt. Only the front of the car had crossed one rail—by which slim margin they escaped.

“Multiple leg fractures,” the doctors told her mother. “She may never walk again. She may be crippled for life.” With Doris they handled the facts more gingerly, but she was a girl who could read between evasions. So she lay alone, weeping for her shattered body and the dreams shattered with it.

As the slow months passed, however, as she moved from hospital to home, from bed to crutches, hope and resilient spirit took over. Unable to make with the feet, she made with the pipes—mostly to release her thwarted energies. Mom and Paul put their heads together, the result being a casual call from a friend who happened to teach singing. Casually, he asked Doris to perform. Feeling silly, she did. He said she was a natural. He said she had rhythm and feeling. He thought maybe they should work on her range a little. “You think he’s kidding?” she inquired after he’d gone. “Why should he bother?” shrugged Mom, and went in to fix dinner. From the kitchen a few minutes later she heard the strains of “Tea For Two,” which was normal, followed by another sound which wasn’t. Her daughter beating out a jubilant tap routine on crutches.

Not until fourteen months after the accident could Doris navigate under her own steam, but she made the time count. At the same local shindigs where her hoofing had once drawn applause, she now hobbled up to sing, and professionals took note. Danny Engel, song plugger, boosted her to Grace Raine, WLW’s voice coach, who offered to iron out the rough spots in her style. Providentially, Doris discarded the crutches just as Barney Rapp prepared to open Sign Of The Drum and called Miss Raine at the radio station. “Got anyone ready for bandwork, Grace?”

“Sure thing,” said Grace with nary a quiver. “Name of Doris Kappelhoff—”

“The name I can’t use, the girl maybe I can. Will you send her over?”

She sang “Day After Day,” and just like that he hired her. “Now about this name—”

“Means something like churchyard,” she told him helpfully.

“And that’s where it belongs—”

“ ‘Day After Day’ was lucky for me, Mr. Rapp. How about Doris Day?”

So she made her professional bow—a slim, freckled girl with corn-colored hair and cornflower eyes. No beauty, but her smile broke like sunlight, radiating friendliness, and her voice held the same quality of warmth, as if she were singing straight to each hearer’s heart. The customers liked her. They liked her well enough to pump up her courage. Greatly daring, she cut a record of “The Wind And The Rain In Your Hair,” sent it to Bob Crosby, then at the Blackhawk in Chicago, tucked a note inside. “I love your band, I would like to sing with you.” The answering wire came while she was at work. Mom phoned her. “It’s signed Bob Crosby!”

“Yes, but what does it say? Stay home?”

“Now you know he’s too smart to say that! He says, ‘Come right up—’ ”

From Crosby to Fred Waring to Les Brown and a ballad called “Sentimental Journey” which rocked the juke-set and spread the name of Doris Day from coast to coast. Only by that time she was Doris Jorden, housewife.

In later years she said: “Twice I loved madly. Insanity’s the word for it—blind, starry-eyed worship.” Not yet eighteen, inexperienced, romantic, impulsive, she gave her heart to Al Jorden, trombonist with Jimmy Dorsey, and retired to domesticity in a cottage on Cincinnati’s Price Hill. As blithely as she’d set out to sing, she quit. Both instinct and training told her that, married, you devote yourself to your husband. What’s an empty career compared to the glory of love? An eager, earnest bride, she proceeded to tackle the range with indifferent results. At ten she’d start cooking. At six she’d hover over Al with her mouth open. “Is it good?” No matter how the meat loaf tasted, the marriage turned sour. No alibi kid, she insists that the blame lay as much with her as with him. Nor could she regret the union which gave her Terry. The year after insanity struck she divorced Jorden and asked the manager of WLW for a job. He gaped. “But, Doris, you’re bigtime now. We can’t pay you more than sustaining rates—sixty-four a week minus taxes—”

“I need the money,” she said.

Money was soon replaced by another problem. It took only the news that Day was again for hire to bring bandleaders flocking. But bandwork meant the road and separation from Terry. Emotions torn, she finally took the long view, signed with Les Brown, left her baby with Mom, and fared forth to seek security for them all. Whenever the outfit worked within hailing distance of home, Mom and Terry joined her, and for a while her hungry arms would be filled.

At the ripe age of twenty-two, she met George Weidler, playing sax for Stan Kenton in New York, and Cupid fitted a second dart to his bow. Though one marriage had flopped, her illusions remained intact, her nature turned trustfully toward the sun of love. Besides, this was different, this was the true flame, the man predestined. Again she quit her job, this time to travel with her husband. Bookings landed them in Hollywood, the housing emergency landed them in a trailer. Anything was fine with Doris as long as she had George. She had him for a fast year.

Even when he pulled out with the band, leaving her behind to nurse the trailer, she refused to admit more than a passing cloud on their happiness. If he seemed moody at times, aren’t we all? If he seemed to be drifting away, she was just over-sensitive. If they quarreled, they always made up, and the first year is the hardest. She loved him better than when she’d married him, and love conquers all. Having spent her first anniversary with loneliness, virus X and budget nightmares, she accepted a month’s engagement from New York’s Little Club.

The story has been told, and by no one more movingly than Doris. “Once I sang a love song in a nightclub with the tears running down my face. Because I’d lost a love that was very important to me. I told myself I’d given that love everything. I told myself I’d never love again.” In her dressingroom she’d picked up a letter in the cherished handwriting. Unsuspecting, she opened it. The blow fell on a wholly vulnerable heart. George felt the whole thing had been a big fat mistake. It wasn’t her fault, she’d been swell, he was sorry, and couldn’t they be friends?

In the midst of her crumbling world came a knock at the door. “Ready, Miss Day?” Like a puppet on strings, she walked out to do her job, and did it—after a fashion. The audience stirred uneasily as a sob caught in her throat, the blue eyes welled and the tears flowed while she sang This Love Of Mine to the bitter end.

In four weeks she lost ten pounds. It was a crushed and miserable girl who returned to Hollywood, got rid of the trailer, moved to the Roosevelt Hotel. She and George had agreed on no divorce yet. Lawyers cost money. Neither contemplated re-marriage. Maybe deep down a spark of hope still lived. If so it flickered too feebly to lighten her grief.

One dat al levy called her. “Meet me at nine tomorrow. We’re due at Warners—”

“What for?”

“To see Mike Curtiz about a movie—”

“You’re crazy, Al—”

“So I’m crazy, so meet me anyway—”

When you have an agent, you go along with his notions, crazy or otherwise. She was grateful to Al. With Marty Melcher and Dick Dorso, he owned Century Artists and from “Sentimental Journey” on, he’d been a Day booster. Because he believed in her, she signed with him, and his opening gun was an effort to sell her to Bob Hope. “Never heard of her,” said Bob. “You will,” Levy assured him. “When I do,” cracked Robert, “bring her around.” It would have been great to sing on the Hope show. Any job would be welcome. But movies! Movies took people who looked like Hedy LaMarr, who could act like Bette Davis. This would have been a laugh if she’d felt like laughing.

Meanwhile Mike Curtiz brooded over a snarl called Romance On The High Seas. With visions of borrowing Betty Hutton, he’d sent her the script. She called back to rave. “We’re in business, Mike.” Ten minutes later her agent called, unnerved. “I don’t know, maybe she’s got a hole in the head. Why?! Because she’s pregnant. Till her baby comes, she couldn’t work for a king. Including you.” Wherefore Mike held his throbbing head in his hands. A million-dollar musical needs a million-dollar star. If not Hutton, then who? His buzzer rang. “Al Levy’s here to see you with a girl singer.”

“Tell him I’m busy.”

For two hours he knocked himself out getting nowhere, then decided that food might generate an idea. In the outer office Levy jumped up. “Mike, this is Doris Day.”

“Not now,” he started, but there the girl stood, so he looked. In his own words: “A look costs you nothing. Often it pays much. I am used to artificial girls with lips rouged. This one looks nice and real. Her hair has a western windblown something. She also looks sad. I like her. I invite them inside. I ask her about experience. Usually, you listen for an hour how they understudied Cornell, how they just missed a Broadway hit. ‘Nothing,’ she says. ‘In school, when I was nine years old, I played a duck.’ Out of my eye I’see Levy starts to sweat, he thinks she doesn’t sell me but her honesty sells me. She is sexy, too, but in an unsexy way. Her sex sneaks up on you. ‘If you feel sad,’ I say, ‘sing me a sad song.’ She sings a song not so sad, “Embraceable You.” The voice is good, but the heart is everything. I tell them, ‘We’ll test.’ ”

The tests run, he communed with himself in the dark projection room. “Mike, you need courage. Go ahead and gamble with the company’s million dollars.” But he staked his own reputation, too, by putting her under personal contract—a contract later sold to Warner Brothers.

Within two weeks Doris was facing the cameras. To her, the whole business seemed unreal. She’d written her mother about the tests. “I don’t know what’ll happen, but I’m not going to worry. If it’s meant to be, it will be.” Such was her state of confusion that, phoning a few days later, she was about to hang up when Mom asked, “What about the movies?”

“Oh, I forgot. I signed a seven-year contract.”

Which doesn’t mean that she underrated her fabulous break. But a seven-year contract, with options, sounds grander than it is, since the studio can drop you at the end of any six months. Not till Romance and its fresh young singing star hit with a major wallop, did Doris feel any security under her feet. And once the rains came, they fell in a golden deluge. “It’s Magic” climbed and crossed the million mark. Bob Hope called Levy. “Why didn’t you tell me about Doris Day?”

“You wouldn’t listen.”

“Well, I’m listening now.”

“Now it’ll cost you.”

“Now she’s worth it,” groaned Hope, and Doris became featured vocalist on his show. Three years after Curtiz took his calculated plunge, she entered the magic circle of Hollywood’s ten top moneymakers.

Her professional triumphs are written in the history of records and radio, in a roll call of pictures down through Calamity Jane and Lucky Me. The coming of Terry and Mom eased her private hurts. In the warmth of home created by her mother, she was at last living under the same roof with her six-year-old, and her first objective was to woo him without disturbing his closeness to the Nana they both loved. Nana helped. When, by long habit, he turned to her, she’d refer him elsewhere. “Whatever your mother says is right.” As for Doris, she took it step by patient step, respected his individuality, refrained from over-demonstraton, grinned “Hi!” when she wanted to cry “Darling!” One day he popped in with a skinned knee and ran to her, instead of Nana, for comfort. She bathed the knee, kissed him, sent him out to play and sat smiling to herself like a freckled mandarin.

But mother and son, however dear, couldn’t fill her life. A career certainly couldn’t. “When you’re not married,” she stated flatly, “you’re lonely.” To escape loneliness, she took a brief spin on the Hollywood merry-go-round, and dropped off with the taste of ashes in her mouth. Financial security wasn’t happiness, success bore no relation to peace. These she found through two men. One had been her husband, one was her husband-to-be.

She met George to discuss their divorce, which wasn’t filed till eighteen months after they separated. As they talked, she watched him with growing wonder. He was a man with quiet eyes who had exchanged tensions for serenity, irresolution for strength. “Something has happened to you!”

“Yes,” he agreed. “Would you like me to tell you about it?”

His way toward inner harmony had led through Christian Science. In that crucial hour, he revealed a new attitude of the spirit which she’d never thought possible to him. At first she listened incredulously, then with mounting eagerness. He told her where to go for guidance. Before long the philosophy of Christian Science captured her, gave her life fresh meaning. Everyone seeks his own road to God. Through one channel or another, Doris’ questing soul would have found hers in the end. She found it sooner because of George Weidler.

“Some day I’ll meet the right man,” she prophesied, “and he won’t be a man who smites me off my feet. I’ve been smitten!”

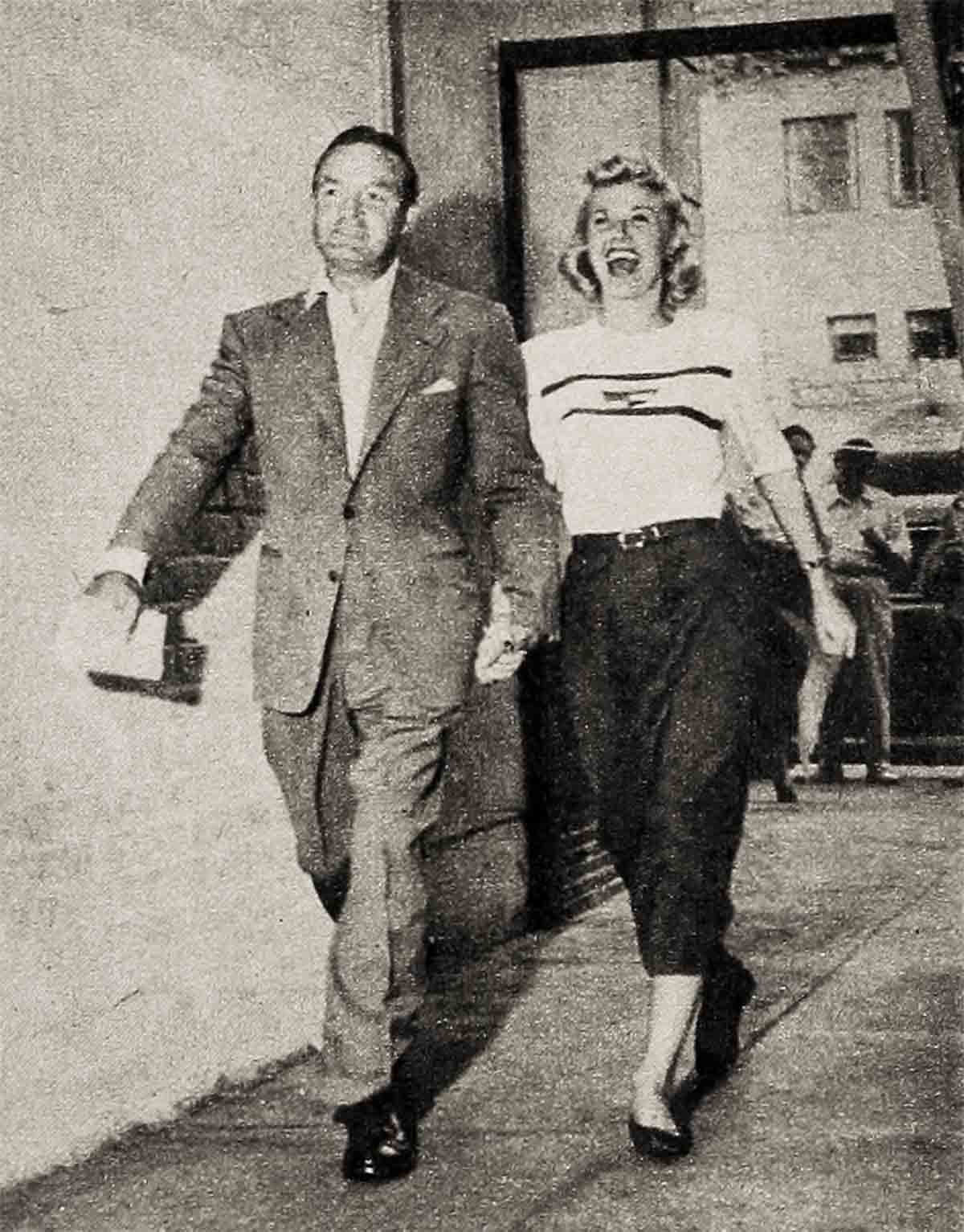

Marty Melcher didn’t smite her, nor did she perform any like service for him. Transacting most of her business with Al Levy, she’d seen his partner around—tall, dark, withdrawn—reportedly heading for divorce from Patti Andrews. Too bad, thought Doris, and dismissed it, a girl who’s all for minding her own affairs.

The first date wasn’t a date. To Melcher, it loomed as a pain in the neck. “I’ve been called out of town,” Levy told him. “Will you take Doris Day to her broadcast tonight, see that everything goes smoothly?” Hooked, Marty canceled his plans as any agent must for a profitable client, saw the job through, prepared to drive the girl home. “I’m hungry,” she said, without ulterior motive. “I’m hungry,” is her theme song. Day or night, she craves food as though she’d been starved from birth.

They stopped in for a snack. Under her native friendliness, Marty thawed a little. He found this blonde Miss Huckleberry Finn (as she’d been tagged by her fans) easy to talk to. He found himself wanting to talk to her again, so he asked her to dinner. As dates multiplied and Hollywood linked their names, both scoffed, “It’s just business.” Maybe they thought so. Maybe, having been burned, they pushed away tenderer possibilities. Maybe they were just kidding themselves. In any case, Doris began leaning on him for services beyond the call of duty. “Marty, can you come over? The faucet’s leaking.” Mom started timing meals for his arrival. Terry shoved his chair so close that the other could barely bend an elbow. “What are you doing that for?” Doris asked.

“Because I like him.”

According to Mom, it was the family doctor who opened her eyes. “Cardiac condition there,” he commented, as fair head and dark vanished into the den with papers to sign. “And a good thing, too. He’s the sort she ought to marry.”

“Marry? Why, he’s here on business!”

“I bet!” chuckled the medic.

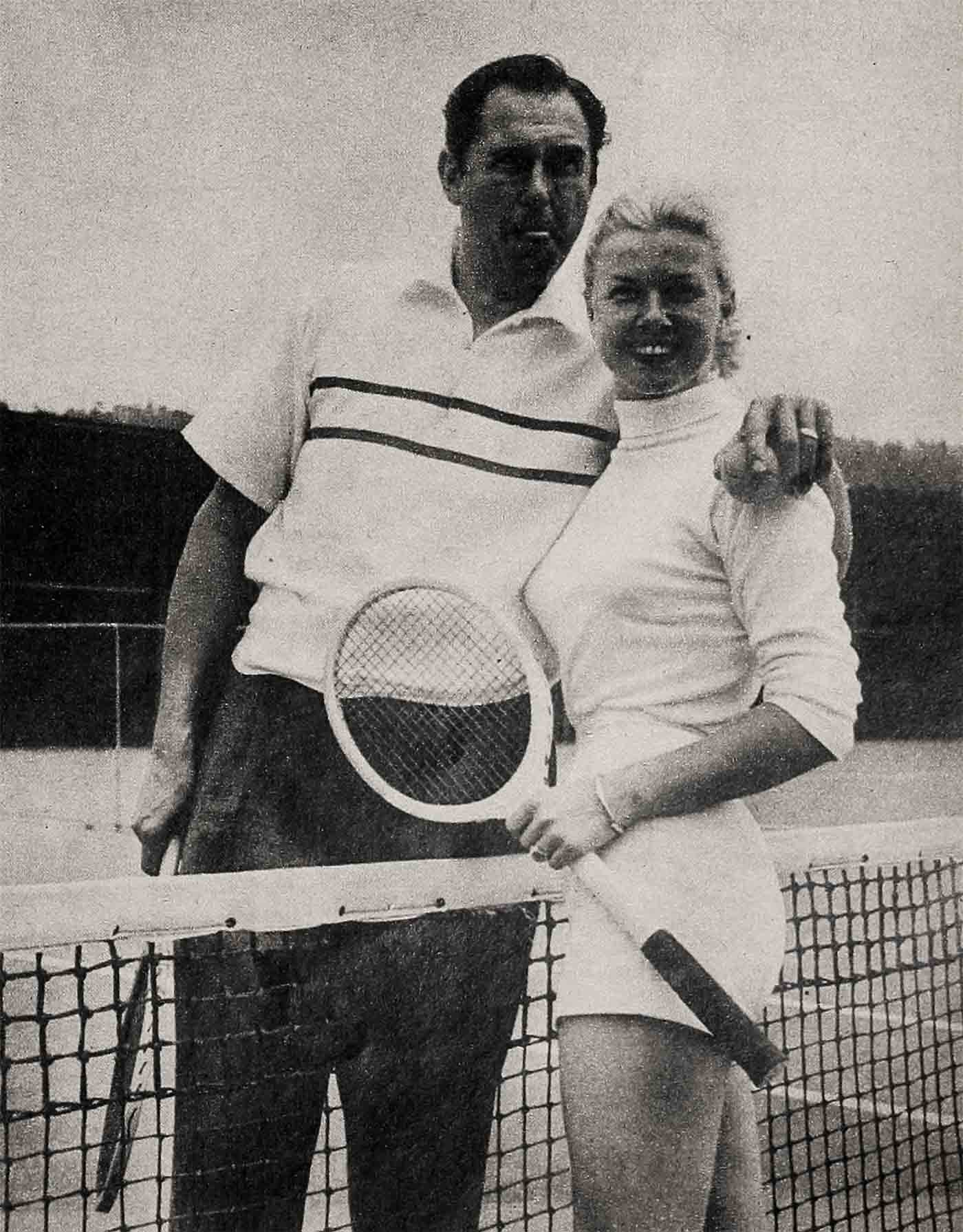

The roots of trust and friendship grew deep before love flowered—or before they acknowledged it to the world. “We’re not engaged,” caroled Dodo. “Nobody planned, nobody promised anything. We’re just in love. We’re just going to be married as soon as we can.” This announcement was preceded by a confab with Terry. You don’t bring husbands into a boy’s home without finding out how the boy stands, as if Doris didn’t know. That night he opened the door to Marty with a flourish and spoke the words of the pure in heart. “Welcome, my intended father!”

Her decree became final in June, 1950, his the following February. Waiting till she finished On Moonlight Bay,they picked her birthday, April 3, for sentimental reasons, and a Burbank justice of the peace to tie the knot simply. If Mom hadn’t shooed them out, they’d have skipped a honeymoon trip altogether. Lured by home and Terry, they docked it to a couple of days. Once formalities could be cleared, Marty adopted Doris’ son as his own. Terry couldn’t be bothered with formalities. The day after the wedding, he wrote his new name large and proud on his spelling paper.

This is the sound marriage Doris hungered for in her teens and at last achieved. Gone is the fever. They’re homebodies, confining their social activities to a circle of intimates. “When you don’t drink, know any gossip or care about hearing same, what’s to do at a party?” she demands.

“I’ve had it,” he counterpoints. “I’d rather look at my wife in blue jeans than any showgirl in sequins, and no entertainer can top Terry for my dough.” Any man and wife must make adjustments to each other. Urbane, articulate Marty sticks them where they belong. “If you’re adult, minor differences don’t annoy you. It’s the old story of the toothpaste cap. If it’s off, let it stay off. Who cares?”

Both offer capsule explanations of their happiness. Says Melcher: “The principle behind marriage is closeness. Doris and I have a talent for staying close. She insists on it and I like it.”

Says Doris: “He’s my understanding husband and my favorite friend.”

He’s her boss now, too. In June she starts Yankee Doodle Girl for Martin Melcher Productions, releasing through Warner Brothers. There’s a segment of Hollywood, smaller than you think, which enjoys sniping. Behind their hands they buzz that Doris got him the job, refusing to sign a‘new contract otherwise. As anyone who knows Melcher will confirm, this is the bunk. An astute operator long before Day ever dawned. on his horizon, he has neither the need nor the make-up to ride anywhere on anybody’s coattails. He’s a solid citizen and Warners got as good as they gave.

Much has also been made of her recent illness. It was quite simple. Like thousands of women yearly; she underwent surgery for the removal.of a benign tumor. Till the tissue is analyzed, benigNancy can’t be 100% determined. We daresay other thousands suffered just such an emotional shock as hers. Not being movie stars, the limelight left them to deal with their nerves in private. For Doris, still ‘another complicating factor entered. Her faith advocates healing through prayer. Doctors insisted on surgery. In the end. she bowed to their judgment, but the conflict tore at her. If during this period, Marty stood like a bulldog between her and the curious, what husband wouldn’t? If she conserved her energy while making Lucky Me, she showed great good sense. On April 3 they celebrated her birthday and their third anniversary at Palm Springs, and Doris splurged on six evening gowns, indicating that her health and spirits are fine. On which pleasant note, it’s pleasant to leave her.

With one added word. Life has given her plenty, including a bunch of hard knocks. Good luck never spoiled her; bad luck never soured her. Through both she kept, her vision of warmth, clung to the human and ethical values which are richer than stardom. It happens in glamourland as elsewhere, but you’ve got to be equipped.

THE END

—BY IDA ZEITLIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1954

No Comments