The Bing Crosby Myth

Scene One: The set of “Riding High.” Bing Crosby, who has just finished a movie shot, walks past a reporter who has been waiting for him.

“Hi, Bing,” hails the reporter. “What are you doing this summer?”

“Not much,” answers Crosby coldly and, without another word, he walks away.

Scene two: The set of “Mr. Music” several months later. Crosby, on the sidelines, is greeted by the same reporter.

“Hi, Bing.”

“Hi! Nice to see you again!” The crooner then answers many questions about his sons, his pictures and his future plans, completely charming the reporter.

Reporters have good reasons for returning a second time in .spite of any brush-off. 1. Crosby, still the top man in Hollywood, cannot be ignored; 2. They have learned to expect his unorthodox behavior.

Anyone who has observed Bing at close range for any length of time can see why he reaps so much bad publicity. There is, generally, a mistaken notion of what the man is really like. Too many people, identifying Bing with the characters he plays, think of him as a gay, unworried minstrel with a song and a good word for everyone. All of which is a mistake. Bing Crosby is no more Father O’Malley than Jack Benny is tight-fisted or Dennis Day is stupid.

Bing Crosby is not an American legend put together by a string of radio and movie writers. He’s a mature citizen, far more complex, and by the same token, far more interesting than the characters he plays. But because he does not act according to his professional counterpart, people are disappointed, disillusioned and angry. Then comes the bad publicity.

First of all, Bing’s Irish. Like other Irishmen, he doesn’t give a hoot what other people think. He lives his life as he pleases, and criticism be damned.

Also, like other Irishmen, he has moods and tempers. He never blows his top, however. When the pressure of dull details and boring people bears down, he retires in sullen silence behind an iron curtain. And Crosby’s Iron Curtain would make Joe Stalin seem like a chatterbox. “He can spot a phony a mile away,” says a friend. “He hates ’em.” He also hates people who pester him for favors or bother him with petty matters when his mind is on something else.

For such persons, Bing has perfected a chilling stare that is a masterpiece. The Crosby features become inert and his eyes, assuming a listless glare, stare right through the petitioner as though he were made of glass.

Bing, shy, hates large gatherings. He shuns crowds and makes as few public appearances as possible. I have seen him at only two large Hollywood parties, both of them in his honor. There have been many other affairs which he was supposed to attend, but didn’t.

A notable Crosby nonappearance was at the testimonial dinner the Friars Club gave Bob Hope a few years ago. Bing, one of the top officers in the club (although he had never attended one of its meetings), was listed as a speaker. No one doubted he would be on hand to honor his pal Hope. But the chair set at the speaker’s table for Bing remained empty.

When he was criticized for staying away, he said, “My friendship for Bob doesn’t depend on appearing at testimonials.” Bob, however, was genuinely hurt, and the incident marked a break in their fabulous friendship.

He’s like that. Bing won’t be stampeded into anything. I recall the presidential race in 1940. The Crosby brothers announced that Bing advocated the election of Dewey over Roosevelt Bing has never taken part in politics, so reporters were anxious to confirm the news. They reached him, finally, on a hunting trip. Was he taking part in the campaign?

“Who’s running?” was the only answer.

His reluctance to appear publicly is also due to his baldness. He wears a toupee only when it is necessary in a movie scene. He hates the thing, not only because he feels it is silly, but also because it is painful to wear and to remove.

His distaste for displaying his baldness has placed him at odds with Hollywood press photographers. Few photos have ever been taken of the Crosby pate, mainly because he often wears a hat or says “no pictures” when it is exposed.

But that is not the only reason for his war with the lensers. He is a busy man, with a multitude of million-dollar enterprises. Posing for pictures takes valuable time. So he dodges it whenever possible.

“People don’t want to see me,” he claims. “They want to hear me.”

He hates prying interviews and small talk. But if a reporter will fire plain, direct questions, Bing will deliver plain, direct answers. He seldoms ducks a query, mainly because interviewers are conditioned in advance not to ask anything too personal.

Asked recently if he had any theory about publicity, Bing replied, “Naw, I’m just too lazy to worry about it.”

Is he lazy? Most people think so. Says Bob Hope, “I’ll tell you how lazy Bing is. If he made his own picture, he’d show himself looking through a knothole in the first scene. The rest of the picture would be what he saw!”

Bing’s easygoing manner makes him seem lazy. But would a lazy man make two or three pictures a year, conduct his own production company, appear on radio shows, record more songs than any other star, and engage in a dozen or more business ventures?

He gives his impression of laziness because he likes to do things the easy way. He wants to live as normal a life as he can, despite back-breaking duties. So he avoids, as much as he can, all the boring details of being a star. He seeks shortcuts, too; as, for instance, his air show.

He disliked the nagging weekly deadline of a radio program. When tape recording was introduced after the war, he decided he wanted to record his show at his own convenience. His network, NBC, was horrified; it allowed only “live” shows. So Bing carted his troupe over to ABC. Now, a sizable percentage of the big programs are transcribed on all the networks.

Such time-savings allow Bing to get away from the whirl of the entertainment world. He spends many evenings at home, studying movies, television shows and records of songs and radio programs. He also spends as much time as possible with his sons.

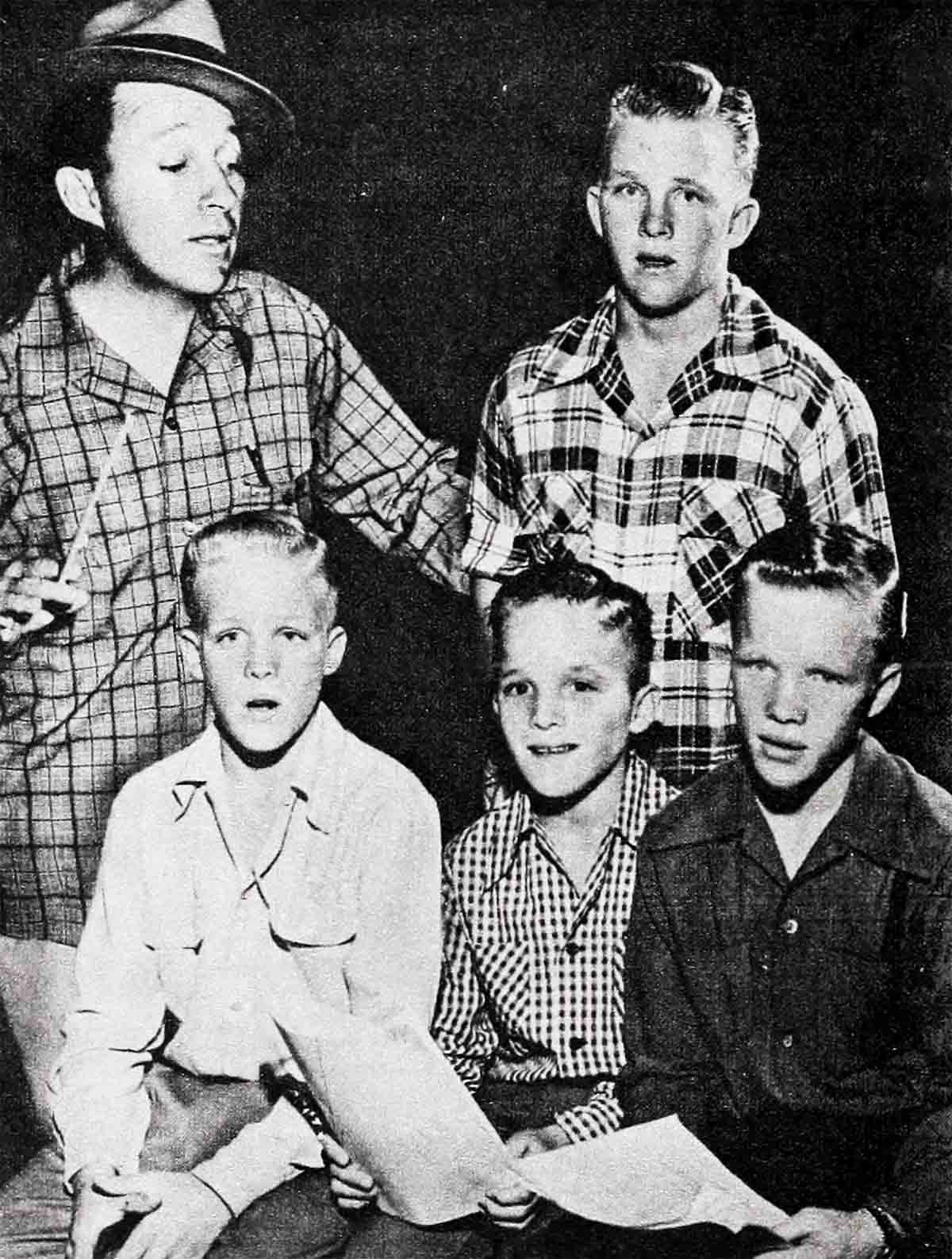

He’s a stern father and a strict disciplinarian. A photographer once asked to take some pictures of the boys on the ranch. “Okay,” said Bing. The photographer got his pictures, during a half-hour of the boys’ lunch period.

The boys’ maternal grandfather thought they were worked too hard. Bing’s answer, “No harder than I worked at their age.”

He makes a determined effort to assure that his four sons will grow up as normal American kids. Once, he was alarmed when the principal of their school in northern California telephoned him in Hollywood. The boys, it seems, were bragging of their father’s wealth.

He flew up to the school at once. One by one, he took each boy into a room for questioning. The three oldest professed innocence. Then Bing talked to Lindsay.

“Well,” the lad said hesitantly, “the only thing I ever said was that you make a lot of money, but the government takes most of it and the relatives take the rest.”

When the boys were younger, they appeared in a couple of pictures. Then Bing stopped their budding careers. “They were getting too hammy,” he explained.

Now, about once a year, they appear on the air shows and this year Gary created news by displaying a well-pitched, adolescent singing voice. However, if any of them have singing ambitions, they will have to wait until they finish college.

Much has been written about the wild-hued Crosby clothes. With good reason. Bing’s color-blind. The kids have fun with this failing. Once, Bing came to his air show in a pair of reddish-mauve slacks and a gaudy sport shirt. Before going on the air, he asked the audience, “How do you like my new gray slacks?”

He was surprised when the audience roared. “Well, Gary told me they were gray,” he said.

While his eyes cannot determine colors, there is nothing wrong with his ears. His pitch is perfect, and that is a major factor that has made his untutored voice the most popular in history. His amazing hearing was described by a friend.

“Bing could be at a party talking intently to Henry Ginsberg, the head of Paramount, stop, correct something said in feet away something that had been said in a third conversation at the same time!”

His memory for faces was illustrated during “The Emperor Waltz” locations in Canada. On his first day there he was introduced to scores of people, including the little daughter of the town baker.

Three weeks later, she was bicycling Bing saw her and shouted, “Hi, Linda, how’s the bakery?”

He doesn’t fret about rumors or criticisms. Recently, a national magazine stated that his voice isn’t what it used to be.

“So what?” was his answer. “I never claimed I could sing in the first place.”

He sings because he loves singing. And he sings all the time—during rehearsals, on the golf course or even during lulls in a conversation.

His charities are many. He gives $75,000 annually to his alma mater, Gonzaga College. Most of his other bequests are secret. He has a large number of old-time friends on his payroll. It’s doubtful if he will ever retire, partly because so many people are dependent on him. On the subject of retirement, he says: “I’ll always remember what George M. Cohan told me, “They’ve got to be still applauding when you reach your dressing room; if they stop when you’re in the wings, then it’s time to quit.’

“I’ll keep singing as long as people want to hear me.”

Still a king of the entertainment world, at forty-six, he continues to feel responsibilities deeply and hopes nothing will happen to his voice.

Bing, for the most part, lives within himself. His inner joys and sorrows are all his own and no one else’s. Once, he entertained a gag writer at his home. It was a weekend of songs and laughs. Quietly, Bing remarked, “I like you.”

The gagster was surprised.

“I like you,” Bing continued, “because you don’t ask me any questions.”

That is Bing!

THE END

—BY BOB THOMAS

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1950